Wairua and Wellbeing : Exploratory Perspectives from Wahine Maori

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2001, Tanglewood

SEMI OIAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR • i DALE CHIHULY INSTALLATIONS AND SCULPTURE / "^ik \ *t HOLSTEN GALLERIES CONTEMPORARY GLASS SCULPTURE ELM STREET, STOCKBRIDGE, MA 01262 . ( 41 3.298.3044 www. holstenga I leries * Save up to 70% off retail everyday! Allen-Edmoi. Nick Hilton C Baccarat Brooks Brothers msSPiSNEff3svS^:-A Coach ' 1 'Jv Cole-Haan v2^o im&. Crabtree & Evelyn OB^ Dansk Dockers Outlet by Designs Escada Garnet Hill Giorgio Armani .*, . >; General Store Godiva Chocolatier Hickey-Freeman/ "' ft & */ Bobby Jones '.-[ J. Crew At Historic Manch Johnston & Murphy Jones New York Levi's Outlet by Designs Manchester Lion's Share Bakery Maidenform Designer Outlets Mikasa Movado Visit us online at stervermo OshKosh B'Gosh Overland iMrt Peruvian Connection Polo/Ralph Lauren Seiko The Company Store Timberland Tumi/Kipling Versace Company Store Yves Delorme JUh** ! for Palais Royal Phone (800) 955 SHOP WS »'" A *Wtev : s-:s. 54 <M 5 "J* "^^SShfcjiy ORIGINS GAUCftV formerly TRIBAL ARTS GALLERY, NYC Ceremonial and modern sculpture for new and advanced collectors Open 7 Days 36 Main St. POB 905 413-298-0002 Stockbridge, MA 01262 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Ray and Maria Stata Music Directorship Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Twentieth Season, 2000-2001 SYMPHONY HALL CENTENNIAL SEASON Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas, President Julian Cohen, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Deborah B. Davis, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Nina L. Doggett, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson John F. Cogan, Jr. Edna S. -

Māori Land and Land Tenure in New Zealand: 150 Years of the Māori Land Court

77 MĀORI LAND AND LAND TENURE IN NEW ZEALAND: 150 YEARS OF THE MĀORI LAND COURT R P Boast* This is a general historical survey of New Zealand's Native/Māori Land Court written for those without a specialist background in Māori land law or New Zealand legal history. The Court was established in its present form in 1865, and is still in operation today as the Māori Land Court. This Court is one of the most important judicial institutions in New Zealand and is the subject of an extensive literature, nearly all of it very critical. There have been many changes to Māori land law in New Zealand since 1865, but the Māori Land Court, responsible for investigating titles, partitioning land blocks, and various other functions (some of which have later been transferred to other bodies) has always been a central part of the Māori land system. The article assesses the extent to which shifts in ideologies relating to land tenure, indigenous cultures, and customary law affected the development of the law in New Zealand. The article concludes with a brief discussion of the current Māori Land Bill, which had as one of its main goals a significant reduction of the powers of the Māori Land Court. Recent political developments in New Zealand, to some extent caused by the government's and the New Zealand Māori Party's support for the 2017 Bill, have meant that the Bill will not be enacted in its 2017 form. Current developments show once again the importance of Māori land issues in New Zealand political life. -

Māori and Aboriginal Women in the Public Eye

MĀORI AND ABORIGINAL WOMEN IN THE PUBLIC EYE REPRESENTING DIFFERENCE, 1950–2000 MĀORI AND ABORIGINAL WOMEN IN THE PUBLIC EYE REPRESENTING DIFFERENCE, 1950–2000 KAREN FOX THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Fox, Karen. Title: Māori and Aboriginal women in the public eye : representing difference, 1950-2000 / Karen Fox. ISBN: 9781921862618 (pbk.) 9781921862625 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Women, Māori--New Zealand--History. Women, Aboriginal Australian--Australia--History. Women, Māori--New Zealand--Social conditions. Women, Aboriginal Australian--Australia--Social conditions. Indigenous women--New Zealand--Public opinion. Indigenous women--Australia--Public opinion. Women in popular culture--New Zealand. Women in popular culture--Australia. Indigenous peoples in popular culture--New Zealand. Indigenous peoples in popular culture--Australia. Dewey Number: 305.4880099442 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover image: ‘Maori guide Rangi at Whakarewarewa, New Zealand, 1935’, PIC/8725/635 LOC Album 1056/D. National Library of Australia, Canberra. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Abbreviations . ix Illustrations . xi Glossary of Māori Words . xiii Note on Usage . xv Introduction . 1 Chapter One . -

Defending the High Ground

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. i ‘Defending the High Ground’ The transformation of the discipline of history into a senior secondary school subject in the late 20th century: A New Zealand curriculum debate A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Education Massey University (Palmerston North) New Zealand (William) Mark Sheehan 2008 ii One might characterise the curriculum reform … as a sort of tidal wave. Everywhere the waves created turbulence and activity but they only engulfed a few small islands; more substantial landmasses were hardly touched at all [and]…the high ground remained completely untouched. Ivor F. Goodson (1994, 17) iii Abstract This thesis examines the development of the New Zealand secondary school history curriculum in the late 20th century and is a case study of the transformation of an academic discipline into a senior secondary school subject. It is concerned with the nature of state control in the development of the history curriculum at this level as well as the extent to which dominant elites within the history teaching community influenced the process. This thesis provides a historical perspective on recent developments in the history curriculum (2005-2008) and argues New Zealand stands apart from international trends in regards to history education. Internationally, curriculum developers have typically prioritised a narrative of the nation-state but in New Zealand the history teaching community has, by and large, been reluctant to engage with a national past and chosen to prioritise English history. -

Memorial Tributes: Volume 15

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS This PDF is available at http://nap.edu/13160 SHARE Memorial Tributes: Volume 15 DETAILS 444 pages | 6 x 9 | HARDBACK ISBN 978-0-309-21306-6 | DOI 10.17226/13160 CONTRIBUTORS GET THIS BOOK National Academy of Engineering FIND RELATED TITLES Visit the National Academies Press at NAP.edu and login or register to get: – Access to free PDF downloads of thousands of scientific reports – 10% off the price of print titles – Email or social media notifications of new titles related to your interests – Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. (Request Permission) Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 15 Memorial Tributes NATIONAL ACADEMY OF ENGINEERING Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 15 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 15 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF ENGINEERING OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Memorial Tributes Volume 15 THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS Washington, D.C. 2011 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 15 International Standard Book Number-13: 978-0-309-21306-6 International Standard Book Number-10: 0-309-21306-1 Additional copies of this publication are available from: The National Academies Press 500 Fifth Street, N.W. Lockbox 285 Washington, D.C. 20055 800–624–6242 or 202–334–3313 (in the Washington metropolitan area) http://www.nap.edu Copyright 2011 by the National Academy of Sciences. -

Internal Assessment Resource History for Achievement Standard 91002

Exemplar for internal assessment resource History for Achievement Standard 91002 Exemplar for Internal Achievement Standard History Level 1 This exemplar supports assessment against: Achievement Standard 91002 Demonstrate understanding of an historical event, or place, of significance to New Zealanders An annotated exemplar is an extract of student evidence, with a commentary, to explain key aspects of the standard. These will assist teachers to make assessment judgements at the grade boundaries. New Zealand Qualification Authority To support internal assessment from 2014 © NZQA 2014 Exemplar for internal assessment resource History for Achievement Standard 91002 Grade Boundary: Low Excellence For Excellence, the student needs to demonstrate comprehensive understanding of an 1. historical event, or place, of significance to New Zealanders. This involves including a depth and breadth of understanding using extensive supporting evidence, to show links between the event, the people concerned and its significance to New Zealanders. In this student’s evidence about the Maori Land Hikoi of 1975, some comprehensive understanding is demonstrated in comments, such as why the wider Maori community became involved (3) and how and when the prime minister took action against the tent embassy (6). Breadth of understanding is demonstrated in the wide range of matters that are considered (e.g. the social background to the march, the nature of the march, and the description of a good range of ways in which the march was significant to New Zealanders). Extensive supporting evidence is provided regarding the march details (4) and the use of specific numbers (5) (7) (8). To reach Excellence more securely, the student could ensure that: • the relevance of some evidence is better explained (1) (2), or omitted if it is not relevant • the story of the hikoi is covered in a more complete way. -

Peter Feeney and Family Explore the Off-Season Pleasures of the Hokianga

+ Travel View across Hokianga Harbour from Omapere. upe, the Polynesian navigator who discovered New Zealand, parcelled out the rest of the country K but was careful to keep the jewel in the crown, the Hokianga, to himself. Kupe journeyed from the legendary Hawaiki, and hats off to him, because come Friday night the three-and-a-half-hour drive there can feel a trifle daunting to your average work-worn Aucklander. It’s a trip best saved, as my wife and three children did, for a long weekend. The route to get there is via Dargaville, which takes you off the beaten track. From the Brynderwyn turn-off, traffic evaporates and a scenic drive commences through a small towns-and-countryside landscape that reminds me of the New Zealand I grew up in. We set off gamely one Friday morning with Edith Piaf’s “Je ne regrette rien” blaring on the car stereo, our four-year-old’s choice (lest Frankie be accused of a cultural sophistication beyond her years, it must be said that the tune is from the movie Madagascar III). But somewhere around that darn wrong turn near Dargaville, the patience of our one-year-old, Tilly, finally snapped, along with our nerves. By then Piaf’s signature tune, looped for the hundredth time, began to lose some of its shine. Midway through the gut-churning bends of the Waipoua Forest, Tane Mahuta, our tallest tree, appeared just in time for a pit-stop that saved us from internal familial combustion, and provoked six-year-old Arlo’s comment that he’d certainly seen bigger trees, only This Way he couldn’t quite remember where… Our home for the next four days was my sister Margaret’s stately house, where she enjoys multimillion-dollar views over the harbour in return for a laughable (by Auckland standards) rent. -

Wai 2700 the CHIEF HISTORIAN's PRE-CASEBOOK

Wai 2700, #6.2.1 Wai 2700 THE CHIEF HISTORIAN’S PRE-CASEBOOK DISCUSSION PAPER FOR THE MANA WĀHINE INQUIRY Kesaia Walker Principal Research Analyst Waitangi Tribunal Unit July 2020 Author Kesaia Walker is currently a Principal Research Analyst in the Waitangi Tribunal Unit and has completed this paper on delegation and with the advice of the Chief Historian. Kesaia has wide experience of Tribunal inquiries having worked for the Waitangi Tribunal Unit since January 2010. Her commissioned research includes reports for Te Rohe Pōtae (Wai 898) and Porirua ki Manawatū (Wai 2200) district inquiries, and the Military Veterans’ (Wai 2500) and Health Services and Outcomes (Wai 2575) kaupapa inquiries. Acknowledgements Several people provided assistance and support during the preparation of this paper, including Sarsha-Leigh Douglas, Max Nichol, Tui MacDonald and Therese Crocker of the Research Services Team, and Lucy Reid and Jenna-Faith Allan of the Inquiry Facilitation Team. Thanks are also due to Cathy Marr, Chief Historian, for her oversight and review of this paper. 2 Contents Purpose of the Chief Historian’s pre-casebook research discussion paper (‘exploratory scoping report’) .................................................................................................................... 4 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 4 The Mana Wāhine Inquiry (Wai 2700) ................................................................................. 7 -

The Governor-General of New Zealand Dame Patsy Reddy

New Zealand’s Governor General The Governor-General is a symbol of unity and leadership, with the holder of the Office fulfilling important constitutional, ceremonial, international, and community roles. Kia ora, nga mihi ki a koutou Welcome “As Governor-General, I welcome opportunities to acknowledge As New Zealand’s 21st Governor-General, I am honoured to undertake success and achievements, and to champion those who are the duties and responsibilities of the representative of the Queen of prepared to assume leadership roles – whether at school, New Zealand. Since the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, the role of the Sovereign’s representative has changed – and will continue community, local or central government, in the public or to do so as every Governor and Governor-General makes his or her own private sector. I want to encourage greater diversity within our contribution to the Office, to New Zealand and to our sense of national leadership, drawing on the experience of all those who have and cultural identity. chosen to make New Zealand their home, from tangata whenua through to our most recent arrivals from all parts of the world. This booklet offers an insight into the role the Governor-General plays We have an extraordinary opportunity to maximise that human in contemporary New Zealand. Here you will find a summary of the potential. constitutional responsibilities, and the international, ceremonial, and community leadership activities Above all, I want to fulfil New Zealanders’ expectations of this a Governor-General undertakes. unique and complex role.” It will be my privilege to build on the legacy The Rt Hon Dame Patsy Reddy of my predecessors. -

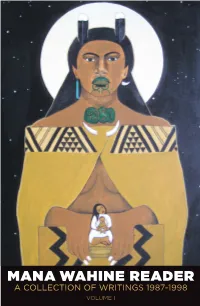

MANA WAHINE READER a COLLECTION of WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader a Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I

MANA WAHINE READER A COLLECTION OF WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I I First Published 2019 by Te Kotahi Research Institute Hamilton, Aotearoa/ New Zealand ISBN: 978-0-9941217-6-9 Education Research Monograph 3 © Te Kotahi Research Institute, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Design Te Kotahi Research Institute Cover illustration by Robyn Kahukiwa Print Waikato Print – Gravitas Media The Mana Wahine Publication was supported by: Disclaimer: The editors and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to reproduce the material within this reader. Every attempt has been made to ensure that the information in this book is correct and that articles are as provided in their original publications. To check any details please refer to the original publication. II Mana Wahine Reader | A Collection of Writings 1987-1998, Volume I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I Edited by: Leonie Pihama, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Naomi Simmonds, Joeliee Seed-Pihama and Kirsten Gabel III Table of contents Poem Don’t Mess with the Māori Woman - Linda Tuhiwai Smith 01 Article 01 To Us the Dreamers are Important - Rangimarie Mihomiho Rose Pere 04 Article 02 He Aha Te Mea Nui? - Waerete Norman 13 Article 03 He Whiriwhiri Wahine: Framing Women’s Studies for Aotearoa Ngahuia Te Awekotuku 19 Article 04 Kia Mau, Kia Manawanui -

Forum H a N D B O

Forum at Te Papa, 31 March - 1 April 2011 Wellington • New Zealand FORUM HANDBOOK Forum at Te Papa 31 March - 1 April 2011 Wellington, New Zealand Contents Convenor Professor Martin Manning Welcome 1 Organising Committee Dr Morgan Williams (Chair) Professor Peter Barrett The New Zealand Climate Change 2 Judy Lawrence Research Institute (CCRI) Supported by Liz Thomas Forum Scope 2 Glenda Lewis Professor Jonathan Boston Chairs & speakers 3 Professor John McClure Dr Taciano Milfont Café & Breakfast sessions 9 Conference Secretariat Conferences & Events Ltd chairs and panelists Level 41-47 Dixon Street Wellington Facilitators & rapporteurs 11 Email: [email protected] Tel: +64 4 384 1511 Additional Events 13 Website http://www.confer.co.nz/ Programme 14 climate_futures General Information 16 Speaker Abstracts 18 Supported by We are grateful for the extremely generous support of Dr Lee Seng Tee, Singapore. Also supported by Wellington City Council. Forum at Te Papa 31 March - 1 April 2011 Wellington, New Zealand Welcome he issues that future climate change raises for will have two speakers and two dialogue groups and society go far beyond climate science itself followed by a short summing up. and lead to basic questions about how society We look forward to your contribution. Tshould respond to likely climate change futures. Dealing with the effects of changes in our climate, and with ways of limiting those changes, will require increasing collaboration between different sectors of society, both locally and globally. It also raises the need for new ways of addressing the likely consequences in the next decade, as well as those for Professor Martin Manning future generations. -

Accepted Version

ACCEPTED VERSION Greg Taylor Knighthoods and the Order of Australia Australian Bar Review, 2020; 49(2):323-356 © LexisNexis Originally published at: https://advance.lexis.com/api/permalink/67b2d078-2ef4-4129-9bab- 769338b75b36/?context=1201008&federationidp=TVWWFB52415 PERMISSIONS https://www.lexisnexis.com.au/en/products-and-services/lexisnexis-journals/open-access-repositories-and- content-sharing Open Access Repositories The final refereed manuscript may be uploaded to SSRN, the contributors' personal or university website or other open access repositories. The final publisher version including any editing, typesetting or LexisNexis pdf pages may not be uploaded. Contributors must note the journal in which the work is published and provide the full publication citation. After 24 months from the date of publication, the final published version, including any editing, typesetting or LexisNexis pdf pages, may be made available on open access repositories including the contributors' personal websites and university websites. In no case may the published article or final accepted manuscript be uploaded to a commercial publisher's website. Content Sharing via Social Media LexisNexis encourages authors to promote their work responsibly. Authors may share abstracts only to social media platforms. They must include the journal title and the full citation. Authors may tag LexisNexis so we can help promote your work via our network, when possible. 1 December 2020 http://hdl.handle.net/2440/129168 KNIGHTHOODS AND THE ORDER OF AUSTRALIA Greg Taylor* Abstract This article considers the legal basis and functioning of the Order of Australia in general, with special reference to the innovations under the prime ministership of Tony Abbott : his two schemes for again awarding Knighthoods in the Order, the first of which bypassed the Council of the Order, as well as his decision to award a Knighthood to Prince Philip.