Theodore's Peace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Evidence of Farming Appears; Stone Axes, Antler Combs, Pottery in Common Use

BC c.5000 - Neolithic (new stone age) Period begins; first evidence of farming appears; stone axes, antler combs, pottery in common use. c.4000 - Construction of the "Sweet Track" (named for its discoverer, Ray Sweet) begun; many similar raised, wooden walkways were constructed at this time providing a way to traverse the low, boggy, swampy areas in the Somerset Levels, near Glastonbury; earliest-known camps or communities appear (ie. Hembury, Devon). c.3500-3000 - First appearance of long barrows and chambered tombs; at Hambledon Hill (Dorset), the primitive burial rite known as "corpse exposure" was practiced, wherein bodies were left in the open air to decompose or be consumed by animals and birds. c.3000-2500 - Castlerigg Stone Circle (Cumbria), one of Britain's earliest and most beautiful, begun; Pentre Ifan (Dyfed), a classic example of a chambered tomb, constructed; Bryn Celli Ddu (Anglesey), known as the "mound in the dark grove," begun, one of the finest examples of a "passage grave." c.2500 - Bronze Age begins; multi-chambered tombs in use (ie. West Kennet Long Barrow) first appearance of henge "monuments;" construction begun on Silbury Hill, Europe's largest prehistoric, man-made hill (132 ft); "Beaker Folk," identified by the pottery beakers (along with other objects) found in their single burial sites. c.2500-1500 - Most stone circles in British Isles erected during this period; pupose of the circles is uncertain, although most experts speculate that they had either astronomical or ritual uses. c.2300 - Construction begun on Britain's largest stone circle at Avebury. c.2000 - Metal objects are widely manufactured in England about this time, first from copper, then with arsenic and tin added; woven cloth appears in Britain, evidenced by findings of pins and cloth fasteners in graves; construction begun on Stonehenge's inner ring of bluestones. -

The Saxon Cathedral at Canterbury and the Saxon

1 29 078 PUBLICATIONS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER THE SAXON CATHEDRAL AT" CANTERBURY AND THE SAXON SAINTS BURIED THEREIN Published by the University of Manchester at THE UNIVERSITY PRESS (H. M. MCKECHNIE, M.A., Secretary) 23 LIME GROTE, OXFORD ROAD, MANCHESTER THE AT CANTEViVTHESAXg^L CATHEDRAL SAXON SAINTS BURIED THEffilN BY CHARLES COTTON, O.B.E., F.R.C.P.E. Hon. Librarian, Christ Church Cathedral, Canterbury MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS 1929 MADE IN ENGLAND Att rights reserved QUAM DILECTA TABERNACULA How lovely and how loved, how full of grace, The Lord the God of Hosts, His dwelling place! How elect your Architecture! How serene your walls remain: Never moved by, Rather proved by Wind, and storm, and surge, and rain! ADAM ST. VICTOR, of the Twelfth Century. Dr. J. M. Neale's translation in JMediaval Hymns and Sequences. PREFACE account of the Saxon Cathedral at Canterbury, and of the Saxon Saints buried therein, was written primarily for new THISmembers of Archaeological Societies, as well as for general readers who might desire to learn something of its history and organiza- tion in those far-away days. The matter has been drawn from the writings of men long since passed away. Their dust lies commingled with that of their successors who lived down to the time when this ancient Religious House fell upon revolutionary days, who witnessed its dissolution as a Priory of Benedictine Monks after nine centuries devoted to the service of God, and its re-establishment as a College of secular canons. This important change, taking place in the sixteenth century, was, with certain differences, a return to the organization which existed during the Saxon period. -

Celtic Relations of St. Oswald of Northumbria Author(S): J

Celtic Relations of St. Oswald of Northumbria Author(s): J. M. Mackinlay Source: The Celtic Review, Vol. 5, No. 20 (Apr., 1909), pp. 304-309 Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30070180 Accessed: 28-06-2016 10:00 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Celtic Review This content downloaded from 144.82.108.120 on Tue, 28 Jun 2016 10:00:52 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms 304 THE CELTIC REVIEW CELTIC RELATIONS OF ST. OSWALD OF NORTHUMBRIA. J. M. MACKINLAY By relationships I do not mean ties of blood, but ties of circumstance. St. Oswald was Anglic by birth, and ruled over an Anglic people, but at various times during his romantic career he was brought into touch with Celtic influences. When his father, IEthelfrith, King of Northum- bria, was killed in battle in the year 617, and was succeeded by Eadwine, brother-in-law of the dead king, Oswald, who was then about thirteen years of age, had to flee from his native land. He went to the north-west, and along with his elder brother Eanwith and a dozen followers, sought refuge in the monastery of Iona. -

Constructing the Seventh Century

COLLÈGE DE FRANCE – CNRS CENTRE DE RECHERCHE D’HISTOIRE ET CIVILISATION DE BYZANCE TRAVAUX ET MÉMOIRES 17 constructing the seventh century edited by Constantin Zuckerman Ouvrage publié avec le concours de la fondation Ebersolt du Collège de France et de l’université Paris-Sorbonne Association des Amis du Centre d’Histoire et Civilisation de Byzance 52, rue du Cardinal-Lemoine – 75005 Paris 2013 PREFACE by Constantin Zuckerman The title of this volume could be misleading. “Constructing the 7th century” by no means implies an intellectual construction. It should rather recall the image of a construction site with its scaffolding and piles of bricks, and with its plentiful uncovered pits. As on the building site of a medieval cathedral, every worker lays his pavement or polishes up his column knowing that one day a majestic edifice will rise and that it will be as accomplished and solid as is the least element of its structure. The reader can imagine the edifice as he reads through the articles collected under this cover, but in this age when syntheses abound it was not the editor’s aim to develop another one. The contributions to the volume are regrouped in five sections, some more united than the others. The first section is the most tightly knit presenting the results of a collaborative project coordinated by Vincent Déroche. It explores the different versions of a “many shaped” polemical treatise (Dialogica polymorpha antiiudaica) preserved—and edited here—in Greek and Slavonic. Anti-Jewish polemics flourished in the seventh century for a reason. In the centuries-long debate opposing the “New” and the “Old” Israel, the latter’s rejection by God was grounded in an irrefutable empirical proof: God had expelled the “Old” Israel from its promised land and given it to the “New.” In the first half of the seventh century, however, this reasoning was shattered, first by the Persian conquest of the Holy Land, which could be viewed as a passing trial, and then by the Arab conquest, which appeared to last. -

How Could Phenological Records from the Chinese Poems of the Tang and Song Dynasties

https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-2020-122 Preprint. Discussion started: 28 September 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. How could phenological records from the Chinese poems of the Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1260 AD) be reliable evidence of past climate changes? Yachen Liu1, Xiuqi Fang2, Junhu Dai3, Huanjiong Wang3, Zexing Tao3 5 1School of Biological and Environmental Engineering, Xi’an University, Xi’an, 710065, China 2Faculty of Geographical Science, Key Laboratory of Environment Change and Natural Disaster MOE, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China 3Key Laboratory of Land Surface Pattern and Simulation, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Science (CAS), Beijing, 100101, China 10 Correspondence to: Zexing Tao ([email protected]) Abstract. Phenological records in historical documents have been proved to be of unique value for reconstructing past climate changes. As a literary genre, poetry reached its peak period in the Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1260 AD) in China, which could provide abundant phenological records in this period when lacking phenological observations. However, the reliability of phenological records from 15 poems as well as their processing methods remains to be comprehensively summarized and discussed. In this paper, after introducing the certainties and uncertainties of phenological information in poems, the key processing steps and methods for deriving phenological records from poems and using them in past climate change studies were discussed: -

MEDIEVAL DAMASCUS Arabic Book Culture, Library Culture and Reading Culture Is Significantly Enriched.’ Li Guo, University of Notre Dame and MEDIEVAL

PLURALITY KONRAD HIRSCHLER ‘This is a tour de force of ferocious codex dissection, relentless bibliographical probing and imaginative reconstructive storytelling. Our knowledge of medieval MEDIEVAL DAMASCUS DAMASCUS MEDIEVAL Arabic book culture, library culture and reading culture is significantly enriched.’ Li Guo, University of Notre Dame AND MEDIEVAL The first documented insight into the content and DIVERSITY structure of a large-scale medieval Arabic library The written text was a pervasive feature of cultural practices in the medieval Middle East. At the heart of book circulation stood libraries that experienced a rapid expansion from the DAMASCUS twelfth century onwards. While the existence of these libraries is well known, our knowledge of their content and structure has been very limited as hardly any medieval Arabic catalogues have been preserved. This book discusses the largest and earliest medieval library of the PLURALITY AND Middle East for which we have documentation – the Ashrafiya library in the very centre of IN AN Damascus – and edits its catalogue. The catalogue shows that even book collections attached to Sunni religious institutions could hold very diverse titles, including Muʿtazilite theology, DIVERSITY IN AN Shiʿite prayers, medical handbooks, manuals for traders, stories from the 1001 Nights and texts extolling wine consumption. ARABIC LIBRARY ARABIC LIBRARY Listing over two thousand books the Ashrafiya catalogue is essential reading for anybody interested in the cultural and intellectual history of Arabic societies. -

The Lives of the Saints of His Family

'ii| Ijinllii i i li^«^^ CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Cornell University Libraru BR 1710.B25 1898 V.16 Lives of the saints. 3 1924 026 082 689 The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924026082689 *- ->^ THE 3Ltt3e0 of ti)e faints REV. S. BARING-GOULD SIXTEEN VOLUMES VOLUME THE SIXTEENTH ^ ^ «- -lj« This Volume contains Two INDICES to the Sixteen Volumes of the work, one an INDEX of the SAINTS whose Lives are given, and the other u. Subject Index. B- -»J( »&- -1^ THE ilttieg of tt)e ^amtsi BY THE REV. S. BARING-GOULD, M.A. New Edition in i6 Volumes Revised with Introduction and Additional Lives of English Martyrs, Cornish and Welsh Saints, and a full Index to the Entire Work ILLUSTRATED BY OVER 400 ENGRAVINGS VOLUME THE SIXTEENTH LONDON JOHN C. NIMMO &- I NEW YORK : LONGMANS, GREEN, CO. MDCCCXCVIII I *- J-i-^*^ ^S^d /I? Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson &' Co. At the Ballantyne Press >i<- -^ CONTENTS The Celtic Church and its Saints . 1-86 Brittany : its Princes and Saints . 87-120 Pedigrees of Saintly Families . 121-158 A Celtic and English Kalendar of Saints Proper to the Welsh, Cornish, Scottish, Irish, Breton, and English People 159-326 Catalogue of the Materials Available for THE Pedigrees of the British Saints 327 Errata 329 Index to Saints whose Lives are Given . 333 Index to Subjects . ... 364 *- -»J< ^- -^ VI Contents LIST OF ADDITIONAL LIVES GIVEN IN THE CELTIC AND ENGLISH KALENDAR S. -

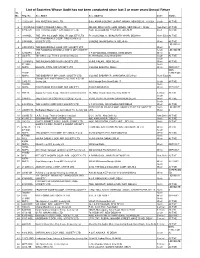

List of Societies Not Audited for Last 3 Years Or More/Annual Return

List of Societies Whose Audit has not been conducted since last 3 or more years/Annual Return Sr. No. Reg. No. Soc. Name Soc. Address Zone Status 1 1232S-GH NAV NIKETAN CGHS LTD B-83, AMAR COLONY, LAJPAT NAGAR, NEW DELHI : 110 024 South ACTIVE 2 1451ND-GH PREETI PRISHAD CGHS LTD. DB-84E, DDA FLATS, HARI NAGAR, NEW DELHI: 110 063 New Delhi ACTIVE 3 875E-GH NAV TARANG COOP. G/H SOCIETY LTD H-26, OLD GOBIND PURA EXT.,DELHI-51 East ACTIVE 4 724-INDL THE JAIN H/L COOP. INDL. (P) SOCIETY LTD. F413 GALI NO. 11, BHAGIRATH VIHAR, DELHI-94 North East ACTIVE THE BAKARWALA COOP. BRICKS KILN (I) 5 24W-INDL SOCIETY LTD. SURERE, NAJAFGARH, N. DELHI-43 West ACTIVE LIQUIDATE 6 24W-NMPS THE BAKARWALA COOP. M/P SOCIETY LTD. West D THE PANDWAL KHOODS COOP N.M.P SOCIETY South LIQUIDATE 7 32-NMPS LTD V.P.O PANDWAL KHOODS, NEW DELHI West D 8 505S-TC The Sikh Coop. Thrift & Credit Society Ltd. 61, Hemkunt Colony, New Delhi- South ACTIVE South 9 124-NMPS THE PALAM COOP N.M.P SOCIETY LTD V&PO, PALAM , NEW DELHI West ACTIVE 211NW- North 10 NMPS BAKAOLI COOL M/P SOCIETY LTD VILLAGE BAKAOLI, DELHI West DEFUNCT NON- 216NE- FUNCTION 11 NMPS THE BABARPUR M/P COOP. SOCIETY LTD. VILLAGE BABARPUR, SHAHDARA, DELHI-32 North East AL Chiragh Delhi Palti Yadram Coop. Thrift & Credit 12 230S-TC Sociey Ltd. 830 Chiragh Delhi,New Delhi-17 South ACTIVE 138NW- North 13 NMPS BUKHTAWAR PUR COOP. -

The Venerable Bede Ecclesiastical History of England (731 A.D.)1

1 Primary Source 3.2 THE VENERABLE BEDE ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY OF ENGLAND (731 A.D.)1 The Anglo-Saxon monk and author, known to posterity as the Venerable Bede (c. 672– 735), was apparently a deeply spiritual man described as constantly praising God, even at the last moments of his life, when he could scarcely breathe. A learned scholar with broad knowledge of ancient and early medieval theology and secular writings, he wrote a huge number of works on theology, biblical commentary, the lives of saints, and secular and religious history. His most famous work, excerpted here, recounts the historical development of Britain with a focus on the vibrant evolution of the church. The passage below concerns the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons from paganism to Christianity. Key themes are the care with which missionaries sought to transform customs without giving offense, Christian humility, and how the converts’ belief in miracles wrought in the name of Christ facilitated their conversion. For the complete text online, click here. For a freely accessible audio recording of the book, click here. BOOK I CHAPTER XVII How Germanus the Bishop,2 sailing into Britain with Lupus,3 first quelled the tempest of the sea, and afterwards that of the Pelagians, by Divine power. [429 A.D.] Some few years before their arrival, the Pelagian heresy,4 brought over by Agricola, the son of Severianus, a Pelagian bishop, had corrupted with its foul taint the faith of the Britons. But whereas they absolutely refused to embrace that perverse doctrine, and blaspheme the grace of Christ, yet were not able of themselves to confute the subtilty of the unholy belief by force of argument, they bethought them of wholesome counsels and determined to crave aid of the Gallican5 prelates in that spiritual warfare. -

(1203) SAINT BIRINUS (DECEMBER 3RD, 2020) Suggested Readings: Isaiah 52: 7 – 10; Psalm 67; Matthew 9: 35 – 38. in England B

(1203) SAINT BIRINUS (DECEMBER 3RD, 2020) Suggested Readings: Isaiah 52: 7 – 10; Psalm 67; Matthew 9: 35 – 38. In England by the early 630s bishoprics had been established in Canterbury, Rochester, London Dunwich, York and Lindisfarne, but this left the Anglo-Saxon areas southwest of these dioceses in pagan hands. So, in about AD 634, Pope Honorius sent the Italian monk Birinus to extend the Church in Britain. As was often done in those times, when the duties of a bishop were clearly seen to include evangelism, Birinus was consecrated before he set out. Bede writes that he had promised that he would sow the seed of our holy faith in the most inland and remote regions of the English where no other teacher had been before him…but when he had reached Britain…he found them completely heathen, and decided it would be better to begin to preach the word of God among them rather than seek more distant converts. He landed at the port of Hamwic (now part of Southampton), where he founded the first of a number of churches, and from there travelled round the area ruled by King Cynegils, with a royal site at the former Roman settlement of Dorchester-on-Thames. At this time the Christian Oswald (5th August) had recently become king in Northumbria, and Cynegils was seeking an alliance with him against the pagan kingdom of Mercia. In AD 639 Oswald was in Dorchester, and acted as godfather to Cynegils when Birinus baptized him and his family. The two kings then gave Birinus the town of Dorchester as the centre of a diocese for the area which would become the kingdom of Wessex. -

The Translation of St Oswald's Relics to New Minster, Gloucester: Royal And

Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Please cite this publication as follows: Bintley, M. (2014) The translation of St Oswald’s relics to New Minster, Gloucester: royal and imperial resonances. Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History, 19. pp. 171-181. ISSN 0264-5254. Link to official URL (if available): This version is made available in accordance with publishers’ policies. All material made available by CReaTE is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Contact: [email protected] ABSTRACT The Translation of St Oswald’s Relics to New Minster, Gloucester: Royal and Imperial Resonances The relics of St Oswald were translated to New Minster, Gloucester, in the early tenth century, under the authority of Æthelflæd and Æthelred of Mercia, and Edward the Elder. This was ostensibly to empower the new burh, sited in the ruins of the former Roman town, with the potent relics of one of Anglo-Saxon Christianity’s cornerstones. This article argues that the relics of Oswald were not only brought to Gloucester to enhance its spiritual and ideological importance, but also to take advantage of the mythologies attached to this king, saint, and martyr, which were perpetuated by a contemporary translation of Bede’s Historia ecclesiastica. This work, which emphasizes Oswald’s role in the unification of Northumbria under Christianity, consciously models Oswald on his imperial predecessor Constantine. These and other valuable attendant mythologies may have been consciously appropriated by the Mercians and West Saxons in the early tenth century, thereby staking a claim to the imperial Christian heritage of Rome and Northumbria, and furthering the notion of an Angelcynn that had only recently been promoted by Alfred the Great. -

Your Reputation Deserves Typar Landscape Fabric

YOUR REPUTATION DESERVES TYPAR LANDSCAPE FABRIC. Your reputation can be jeopardized by little to block weeds under decks and in planters, to prevent things. Like weeds. heaving of bricks in patios and walkways, and to mini- Fight back with Typar landscape Fabric, the key to mize erosion. maintenance-free landscaping for your clients. Ask for Typar landscape Fabric for Professionals. Typar is made from rugged polypropylene fabric. It You deserve it. blocks weeds, but is porous enough to let water, air and fertilizer pass through. The result? Healthier soil and plants. Typar leaves all your landscaping projects—and your reputation—looking beautiful longer. There are plenty of other professional uses for Typar: o member of The InterTech Group FOR PROFESSIONALS The Ryan Touch. RYAN Quality equipment for lets you do the job as effectively tings and routine maintenance. So, outstanding results. with less maintenance for as many you'll reduce your downtime while Combine your turf care exper- years as the new Greensaire 24. saving service time between the tise with Ryan turf care equipment, Only with its crank and cam action greens — getting golfers back on and it's a little like working magic do tines go vertically in and out to the course quickly. on your course. Our complete line virtually eliminate side compaction comes with a long history of low- and a ridge around each hole. The Ryan tackles the big jobs, too. maintenance and high performance. result is a smoother putting surface The Ryan Renovaire® is the In fact, the only one who works and better root development.