Constructing the Seventh Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Empires in East Asia

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-A Module 3 Empires in East Asia Essential Question In general, was China helpful or harmful to the development of neighboring empires and kingdoms? About the Photo: Angkor Wat was built in In this module you will learn how the cultures of East Asia influenced one the 1100s in the Khmer Empire, in what is another, as belief systems and ideas spread through both peaceful and now Cambodia. This enormous temple was violent means. dedicated to the Hindu god Vishnu. Explore ONLINE! SS.912.W.2.19 Describe the impact of Japan’s physiography on its economic and political development. SS.912.W.2.20 Summarize the major cultural, economic, political, and religious developments VIDEOS, including... in medieval Japan. SS.912.W.2.21 Compare Japanese feudalism with Western European feudalism during • A Mongol Empire in China the Middle Ages. SS.912.W.2.22 Describe Japan’s cultural and economic relationship to China and Korea. • Ancient Discoveries: Chinese Warfare SS.912.G.2.1 Identify the physical characteristics and the human characteristics that define and differentiate regions. SS.912.G.4.9 Use political maps to describe the change in boundaries and governments within • Ancient China: Masters of the Wind continents over time. and Waves • Marco Polo: Journey to the East • Rise of the Samurai Class • Lost Spirits of Cambodia • How the Vietnamese Defeated the Mongols Document Based Investigations Graphic Organizers Interactive Games Image with Hotspots: A Mighty Fighting Force Image with Hotspots: Women of the Heian Court 78 Module 3 DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-A Timeline of Events 600–1400 Explore ONLINE! East and Southeast Asia World 600 618 Tang Dynasty begins 289-year rule in China. -

Pre-Islamic Arabia

Pre-Islamic Arabia The Nomadic Tribes of Arabia The nomadic pastoralist Bedouin tribes inhabited the Arabian Peninsula before the rise of Islam around 700 CE. LEARNING OBJECTIVES Describe the societal structure of tribes in Arabia KEY TAKEAWAYS Key Points Nomadic Bedouin tribes dominated the Arabian Peninsula before the rise of Islam. Family groups called clans formed larger tribal units, which reinforced family cooperation in the difficult living conditions on the Arabian peninsula and protected its members against other tribes. The Bedouin tribes were nomadic pastoralists who relied on their herds of goats, sheep, and camels for meat, milk, cheese, blood, fur/wool, and other sustenance. The pre-Islamic Bedouins also hunted, served as bodyguards, escorted caravans, worked as mercenaries, and traded or raided to gain animals, women, gold, fabric, and other luxury items. Arab tribes begin to appear in the south Syrian deserts and southern Jordan around 200 CE, but spread from the central Arabian Peninsula after the rise of Islam in the 630s CE. Key Terms Nabatean: an ancient Semitic people who inhabited northern Arabia and Southern Levant, ca. 37–100 CE. Bedouin: a predominantly desert-dwelling Arabian ethnic group traditionally divided into tribes or clans. Pre-Islamic Arabia Pre-Islamic Arabia refers to the Arabian Peninsula prior to the rise of Islam in the 630s. Some of the settled communities in the Arabian Peninsula developed into distinctive civilizations. Sources for these civilizations are not extensive, and are limited to archaeological evidence, accounts written outside of Arabia, and Arab oral traditions later recorded by Islamic scholars. Among the most prominent civilizations were Thamud, which arose around 3000 BCE and lasted to about 300 CE, and Dilmun, which arose around the end of the fourth millennium and lasted to about 600 CE. -

How Could Phenological Records from the Chinese Poems of the Tang and Song Dynasties

https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-2020-122 Preprint. Discussion started: 28 September 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. How could phenological records from the Chinese poems of the Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1260 AD) be reliable evidence of past climate changes? Yachen Liu1, Xiuqi Fang2, Junhu Dai3, Huanjiong Wang3, Zexing Tao3 5 1School of Biological and Environmental Engineering, Xi’an University, Xi’an, 710065, China 2Faculty of Geographical Science, Key Laboratory of Environment Change and Natural Disaster MOE, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China 3Key Laboratory of Land Surface Pattern and Simulation, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Science (CAS), Beijing, 100101, China 10 Correspondence to: Zexing Tao ([email protected]) Abstract. Phenological records in historical documents have been proved to be of unique value for reconstructing past climate changes. As a literary genre, poetry reached its peak period in the Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1260 AD) in China, which could provide abundant phenological records in this period when lacking phenological observations. However, the reliability of phenological records from 15 poems as well as their processing methods remains to be comprehensively summarized and discussed. In this paper, after introducing the certainties and uncertainties of phenological information in poems, the key processing steps and methods for deriving phenological records from poems and using them in past climate change studies were discussed: -

The Migration of Syrian and Palestinian Populations in the 7Th Century: Movement of Individuals and Groups in the Mediterranean

Chapter 10 The Migration of Syrian and Palestinian Populations in the 7th Century: Movement of Individuals and Groups in the Mediterranean Panagiotis Theodoropoulos In 602, the Byzantine emperor Maurice was dethroned and executed in a mili- tary coup, leading to the takeover of Phokas. In response to that, the Sasanian Great King Khosrow ii (590–628), who had been helped by Maurice in 591 to regain his throne from the usurper Bahram, launched a war of retribution against Byzantium. In 604 taking advantage of the revolt of the patrikios Nars- es against Phokas, he captured the city of Dara. By 609, the Persians had com- pleted the conquest of Byzantine Mesopotamia with the capitulation of Edes- sa.1 A year earlier, in 608, the Exarch of Carthage Herakleios the Elder rose in revolt against Phokas. His nephew Niketas campaigned against Egypt while his son, also named Herakleios, led a fleet against Constantinople. Herakleios managed to enter the city and kill Phokas. He was crowned emperor on Octo- ber 5, 610.2 Ironically, three days later on October 8, 610, Antioch, the greatest city of the Orient, surrendered to the Persians who took full advantage of the Byzantine civil strife.3 A week later Apameia, another great city in North Syria, came to terms with the Persians. Emesa fell in 611. Despite two Byzantine counter at- tacks, one led by Niketas in 611 and another led by Herakleios himself in 613, the Persian advance seemed unstoppable. Damascus surrendered in 613 and a year later Caesarea and all other coastal towns of Palestine fell as well. -

MEDIEVAL DAMASCUS Arabic Book Culture, Library Culture and Reading Culture Is Significantly Enriched.’ Li Guo, University of Notre Dame and MEDIEVAL

PLURALITY KONRAD HIRSCHLER ‘This is a tour de force of ferocious codex dissection, relentless bibliographical probing and imaginative reconstructive storytelling. Our knowledge of medieval MEDIEVAL DAMASCUS DAMASCUS MEDIEVAL Arabic book culture, library culture and reading culture is significantly enriched.’ Li Guo, University of Notre Dame AND MEDIEVAL The first documented insight into the content and DIVERSITY structure of a large-scale medieval Arabic library The written text was a pervasive feature of cultural practices in the medieval Middle East. At the heart of book circulation stood libraries that experienced a rapid expansion from the DAMASCUS twelfth century onwards. While the existence of these libraries is well known, our knowledge of their content and structure has been very limited as hardly any medieval Arabic catalogues have been preserved. This book discusses the largest and earliest medieval library of the PLURALITY AND Middle East for which we have documentation – the Ashrafiya library in the very centre of IN AN Damascus – and edits its catalogue. The catalogue shows that even book collections attached to Sunni religious institutions could hold very diverse titles, including Muʿtazilite theology, DIVERSITY IN AN Shiʿite prayers, medical handbooks, manuals for traders, stories from the 1001 Nights and texts extolling wine consumption. ARABIC LIBRARY ARABIC LIBRARY Listing over two thousand books the Ashrafiya catalogue is essential reading for anybody interested in the cultural and intellectual history of Arabic societies. -

Part of Princeton's Climate Change & History Research Initiative

The climate of survival? Environment, climate and society in Byzantine Anatolia, ca. 600-1050 Part of Princeton's Climate Change & History Research Initiative J. Haldon History Department, Princeton University, USA Project Team: Tim Newfield (Princeton); Lee Mordechai (Princeton) Introduction Problem and context No-one doubts that climate, environment and societal development are Between the early 630s and 740s the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) empire lost some The onset of this simplification cannot be made to coincide either with known political linked in causally complex ways. The problem is in the actual mechanics 75% of its territory (Fig. 2) and an equivalent amount in annual revenue to the events, such as the Arab invasions, nor can it be made to fit neatly with any single linking the two, and in trying to determine the causal associations, or in Arab-Islamic conquests or, in the Balkans, to various ‘barbarian’ groups. How did it ‘climate change’ event. In some areas the simplified regime does indeed coincide assigning these causal factors some order of priority. Key questions survive such a catastrophic loss, and how was it able to recover stability and go with the onset of the more humid conditions, in others it begins much later, and in include, for example, at what scale are the climatic and environmental onto the offensive in the later 9th and 10th centuries? There are many factors, as others there is no change at all. So a first conclusion must be that while some farmers events observed, and how does this relate to the societal changes in noted already, but environmental aspects have hitherto been largely disregarded. -

How Ecumenical Was Early Islam?

Near Eastern Languages and Civilization The Farhat J. Ziadeh Distinguished Lecture in Arab and Islamic Studies How Ecumenical Was Early Islam? Professor Fred M. Donner University of Chicago Dear Friends and Colleagues, It is my distinct privilege to provide you with a copy of the eleventh Far- hat J. Ziadeh Distinguished Lecture in Arab and Islamic Studies, “How Ecumenical Was Early Islam?” delivered by Fred M. Donner on April 29, 2013. The Ziadeh Fund was formally endowed in 2001. Since that time, with your support, it has allowed us to strengthen our educational reach and showcase the most outstanding scholarship in Arab and Islamic Studies, and to do so always in honor of our dear colleague Farhat Ziadeh, whose contributions to the fields of Islamic law, Arabic language, and Islamic Studies are truly unparalleled. Farhat J. Ziadeh was born in Ramallah, Palestine, in 1917. He received his B.A. from the American University of Beirut in 1937 and his LL.B. from the University of London in 1940. He then attended Lincoln’s Inn, London, where he became a Barrister-at-Law in 1946. In the final years of the British Mandate, he served as a Magistrate for the Government of Palestine before eventually moving with his family to the United States. He was appointed Professor of Arabic and Islamic Law at Princeton University, where he taught until 1966, at which time he moved to the University of Washington. The annual lectureship in his name is a fitting tribute to his international reputation and his national service to the discipline of Arabic and Islam- ic Studies. -

CP Thin Wall Conduit Fittings (For EMT Conduit)

2: 5: 50: 95: 98: 100: SYS19: BASE2 JOB: CRMAIN06-0273-8 Name: CP-273 DATE: JAN 19 2006 Time: 5:14:19 PM Operator: JB COLOR: CMYK TCP: 15001 Typedriver Name: TS name csm no.: 100 Zoom: 100 Thin Wall Conduit Fittings ɀ Set Screw Type Fittings CP ɀ Compression Type Fittings (For EMT Conduit) ɀ Combination Couplings COMPRESSION TYPE FITTINGS – STEEL ɀ SET SCREW TYPE FITTINGS Couplings CP UL File No. E-22132 Weight Features: Set Screw Type Unit Standard Lbs. Per ɀ Pre-set & Staked Robertson Head Screws Fittings Thinwall Cat. # Size Quantity Package 100 ɀ Male Hub Threads - NPSM ɀ Steel Locknuts 660S 1⁄2⍯ 50 250 12 ɀ Heavy Steel Walls 661S 3⁄4⍯ 25 125 18 ɀ 662 1⍯ 25 100 27 Standard Material: Steel ɀ Standard Finish: Zinc Plated 1 ⍯ 663 1 ⁄4 10 50 46 Concrete Tight 1 ⍯ 664 1 ⁄2 10 50 63 Straight Connectors – Insulated 665 2⍯ 52592UL File No. E-22132 666 21⁄2⍯ 2 10 250 Weight 667 3⍯ 1 5 410 Unit Standard Lbs. Per 668 31⁄2⍯ 1 5 390 Cat. # Size Quantity Package 100 669 4⍯ 1 5 485 1450 1⁄2⍯ 50 250 9 1451 3⁄4⍯ 25 100 14 SET SCREW TYPE FITTINGS 1452 1⍯ 20 100 23 New Space-Saver EMT Connector - Set Screw 1453* 11⁄4⍯ 10 50 46 UL File No. E-22132 1454* 11⁄2⍯ 10 50 50 Features: 1455* 2⍯ 52578 ɀ Used to join EMT conduit to a box or 1456*+ 21⁄2⍯ 2 10 130 enclosure 1457*+ 3⍯ 1 5 140 ɀ Designed with the male threads on the 1458*+ 31⁄2⍯ 1 5 180 locknut, the Space-Saver takes up virtually no 1459*+ 4⍯ 1 5 225 room inside the box, and the smooth pulling surface eliminates the * Two Tightening Screws need for a bushing or insulated throat Straight Connectors – Non-Insulated ɀ Angled teeth on locknut bite into enclosure, preventing loosening UL File No. -

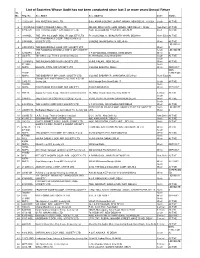

List of Societies Not Audited for Last 3 Years Or More/Annual Return

List of Societies Whose Audit has not been conducted since last 3 or more years/Annual Return Sr. No. Reg. No. Soc. Name Soc. Address Zone Status 1 1232S-GH NAV NIKETAN CGHS LTD B-83, AMAR COLONY, LAJPAT NAGAR, NEW DELHI : 110 024 South ACTIVE 2 1451ND-GH PREETI PRISHAD CGHS LTD. DB-84E, DDA FLATS, HARI NAGAR, NEW DELHI: 110 063 New Delhi ACTIVE 3 875E-GH NAV TARANG COOP. G/H SOCIETY LTD H-26, OLD GOBIND PURA EXT.,DELHI-51 East ACTIVE 4 724-INDL THE JAIN H/L COOP. INDL. (P) SOCIETY LTD. F413 GALI NO. 11, BHAGIRATH VIHAR, DELHI-94 North East ACTIVE THE BAKARWALA COOP. BRICKS KILN (I) 5 24W-INDL SOCIETY LTD. SURERE, NAJAFGARH, N. DELHI-43 West ACTIVE LIQUIDATE 6 24W-NMPS THE BAKARWALA COOP. M/P SOCIETY LTD. West D THE PANDWAL KHOODS COOP N.M.P SOCIETY South LIQUIDATE 7 32-NMPS LTD V.P.O PANDWAL KHOODS, NEW DELHI West D 8 505S-TC The Sikh Coop. Thrift & Credit Society Ltd. 61, Hemkunt Colony, New Delhi- South ACTIVE South 9 124-NMPS THE PALAM COOP N.M.P SOCIETY LTD V&PO, PALAM , NEW DELHI West ACTIVE 211NW- North 10 NMPS BAKAOLI COOL M/P SOCIETY LTD VILLAGE BAKAOLI, DELHI West DEFUNCT NON- 216NE- FUNCTION 11 NMPS THE BABARPUR M/P COOP. SOCIETY LTD. VILLAGE BABARPUR, SHAHDARA, DELHI-32 North East AL Chiragh Delhi Palti Yadram Coop. Thrift & Credit 12 230S-TC Sociey Ltd. 830 Chiragh Delhi,New Delhi-17 South ACTIVE 138NW- North 13 NMPS BUKHTAWAR PUR COOP. -

Basic Study on Oharidadera and Taikoji Temples

Bulletin of the National Museum of Japanese History Vol. 179 November 2013 Basic Study on Oharidadera and Taikoji Temples YOSHIKAWA Shinji The abandoned temple of Okuyama (Okuyama Kumedera Temple) located at Okuyama in Asuka Village, Nara Prefecture is considered to be an old temple founded in the 620s or 630s, and identified with the Oharidadera Temple found in bibliographical sources of olden times. However, with regard to the circumstances of the foundation of the Oharidadera Temple, to date, no firmly established theory has been formed. In this paper by rereading historical materials relating to ancient times through to the medieval period, the following conclusions were obtained. 1. Oharidadera Temple in Asuka was the leading convent in the late 7th century, and even in the 8th century the temple had a close relation with the Imperial Family. It was confirmed that concurrently with the relocation of the capital to Heijyo-kyo, the temple was moved to the northern outskirts of Heijyo-kyo, and the new temple was also called Oharidadera. 2. The Taikoji Temple in Nara, mentioned in historical materials covering the Heian period and later, in view of its geographical position, can be assumed to be the same as the Heijyo Oharidadera Temple. It would be reasonable to consider that Oharidadera Temple had the Buddhist name, Taikoji, since before the relocation of the capital to Heijyo-kyo. 3. Private estates owned by Taikoji Temple in Yamato Province, mentioned in the Kanyo Ruijusho collection, were systematically arranged in locations convenient for overland transportation on the Nakatsu-Michi road and water transport on the Yamato River; against this background a strong admin- istrative and financial power can be inferred. -

The History of Solar

Solar technology isn’t new. Its history spans from the 7th Century B.C. to today. We started out concentrating the sun’s heat with glass and mirrors to light fires. Today, we have everything from solar-powered buildings to solar- powered vehicles. Here you can learn more about the milestones in the Byron Stafford, historical development of solar technology, century by NREL / PIX10730 Byron Stafford, century, and year by year. You can also glimpse the future. NREL / PIX05370 This timeline lists the milestones in the historical development of solar technology from the 7th Century B.C. to the 1200s A.D. 7th Century B.C. Magnifying glass used to concentrate sun’s rays to make fire and to burn ants. 3rd Century B.C. Courtesy of Greeks and Romans use burning mirrors to light torches for religious purposes. New Vision Technologies, Inc./ Images ©2000 NVTech.com 2nd Century B.C. As early as 212 BC, the Greek scientist, Archimedes, used the reflective properties of bronze shields to focus sunlight and to set fire to wooden ships from the Roman Empire which were besieging Syracuse. (Although no proof of such a feat exists, the Greek navy recreated the experiment in 1973 and successfully set fire to a wooden boat at a distance of 50 meters.) 20 A.D. Chinese document use of burning mirrors to light torches for religious purposes. 1st to 4th Century A.D. The famous Roman bathhouses in the first to fourth centuries A.D. had large south facing windows to let in the sun’s warmth. -

Your Reputation Deserves Typar Landscape Fabric

YOUR REPUTATION DESERVES TYPAR LANDSCAPE FABRIC. Your reputation can be jeopardized by little to block weeds under decks and in planters, to prevent things. Like weeds. heaving of bricks in patios and walkways, and to mini- Fight back with Typar landscape Fabric, the key to mize erosion. maintenance-free landscaping for your clients. Ask for Typar landscape Fabric for Professionals. Typar is made from rugged polypropylene fabric. It You deserve it. blocks weeds, but is porous enough to let water, air and fertilizer pass through. The result? Healthier soil and plants. Typar leaves all your landscaping projects—and your reputation—looking beautiful longer. There are plenty of other professional uses for Typar: o member of The InterTech Group FOR PROFESSIONALS The Ryan Touch. RYAN Quality equipment for lets you do the job as effectively tings and routine maintenance. So, outstanding results. with less maintenance for as many you'll reduce your downtime while Combine your turf care exper- years as the new Greensaire 24. saving service time between the tise with Ryan turf care equipment, Only with its crank and cam action greens — getting golfers back on and it's a little like working magic do tines go vertically in and out to the course quickly. on your course. Our complete line virtually eliminate side compaction comes with a long history of low- and a ridge around each hole. The Ryan tackles the big jobs, too. maintenance and high performance. result is a smoother putting surface The Ryan Renovaire® is the In fact, the only one who works and better root development.