'Abd Al-Rahman Ibn Khalid's Invasion, Saporio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constructing the Seventh Century

COLLÈGE DE FRANCE – CNRS CENTRE DE RECHERCHE D’HISTOIRE ET CIVILISATION DE BYZANCE TRAVAUX ET MÉMOIRES 17 constructing the seventh century edited by Constantin Zuckerman Ouvrage publié avec le concours de la fondation Ebersolt du Collège de France et de l’université Paris-Sorbonne Association des Amis du Centre d’Histoire et Civilisation de Byzance 52, rue du Cardinal-Lemoine – 75005 Paris 2013 PREFACE by Constantin Zuckerman The title of this volume could be misleading. “Constructing the 7th century” by no means implies an intellectual construction. It should rather recall the image of a construction site with its scaffolding and piles of bricks, and with its plentiful uncovered pits. As on the building site of a medieval cathedral, every worker lays his pavement or polishes up his column knowing that one day a majestic edifice will rise and that it will be as accomplished and solid as is the least element of its structure. The reader can imagine the edifice as he reads through the articles collected under this cover, but in this age when syntheses abound it was not the editor’s aim to develop another one. The contributions to the volume are regrouped in five sections, some more united than the others. The first section is the most tightly knit presenting the results of a collaborative project coordinated by Vincent Déroche. It explores the different versions of a “many shaped” polemical treatise (Dialogica polymorpha antiiudaica) preserved—and edited here—in Greek and Slavonic. Anti-Jewish polemics flourished in the seventh century for a reason. In the centuries-long debate opposing the “New” and the “Old” Israel, the latter’s rejection by God was grounded in an irrefutable empirical proof: God had expelled the “Old” Israel from its promised land and given it to the “New.” In the first half of the seventh century, however, this reasoning was shattered, first by the Persian conquest of the Holy Land, which could be viewed as a passing trial, and then by the Arab conquest, which appeared to last. -

How Could Phenological Records from the Chinese Poems of the Tang and Song Dynasties

https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-2020-122 Preprint. Discussion started: 28 September 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. How could phenological records from the Chinese poems of the Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1260 AD) be reliable evidence of past climate changes? Yachen Liu1, Xiuqi Fang2, Junhu Dai3, Huanjiong Wang3, Zexing Tao3 5 1School of Biological and Environmental Engineering, Xi’an University, Xi’an, 710065, China 2Faculty of Geographical Science, Key Laboratory of Environment Change and Natural Disaster MOE, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China 3Key Laboratory of Land Surface Pattern and Simulation, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Science (CAS), Beijing, 100101, China 10 Correspondence to: Zexing Tao ([email protected]) Abstract. Phenological records in historical documents have been proved to be of unique value for reconstructing past climate changes. As a literary genre, poetry reached its peak period in the Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1260 AD) in China, which could provide abundant phenological records in this period when lacking phenological observations. However, the reliability of phenological records from 15 poems as well as their processing methods remains to be comprehensively summarized and discussed. In this paper, after introducing the certainties and uncertainties of phenological information in poems, the key processing steps and methods for deriving phenological records from poems and using them in past climate change studies were discussed: -

MEDIEVAL DAMASCUS Arabic Book Culture, Library Culture and Reading Culture Is Significantly Enriched.’ Li Guo, University of Notre Dame and MEDIEVAL

PLURALITY KONRAD HIRSCHLER ‘This is a tour de force of ferocious codex dissection, relentless bibliographical probing and imaginative reconstructive storytelling. Our knowledge of medieval MEDIEVAL DAMASCUS DAMASCUS MEDIEVAL Arabic book culture, library culture and reading culture is significantly enriched.’ Li Guo, University of Notre Dame AND MEDIEVAL The first documented insight into the content and DIVERSITY structure of a large-scale medieval Arabic library The written text was a pervasive feature of cultural practices in the medieval Middle East. At the heart of book circulation stood libraries that experienced a rapid expansion from the DAMASCUS twelfth century onwards. While the existence of these libraries is well known, our knowledge of their content and structure has been very limited as hardly any medieval Arabic catalogues have been preserved. This book discusses the largest and earliest medieval library of the PLURALITY AND Middle East for which we have documentation – the Ashrafiya library in the very centre of IN AN Damascus – and edits its catalogue. The catalogue shows that even book collections attached to Sunni religious institutions could hold very diverse titles, including Muʿtazilite theology, DIVERSITY IN AN Shiʿite prayers, medical handbooks, manuals for traders, stories from the 1001 Nights and texts extolling wine consumption. ARABIC LIBRARY ARABIC LIBRARY Listing over two thousand books the Ashrafiya catalogue is essential reading for anybody interested in the cultural and intellectual history of Arabic societies. -

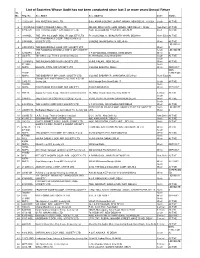

List of Societies Not Audited for Last 3 Years Or More/Annual Return

List of Societies Whose Audit has not been conducted since last 3 or more years/Annual Return Sr. No. Reg. No. Soc. Name Soc. Address Zone Status 1 1232S-GH NAV NIKETAN CGHS LTD B-83, AMAR COLONY, LAJPAT NAGAR, NEW DELHI : 110 024 South ACTIVE 2 1451ND-GH PREETI PRISHAD CGHS LTD. DB-84E, DDA FLATS, HARI NAGAR, NEW DELHI: 110 063 New Delhi ACTIVE 3 875E-GH NAV TARANG COOP. G/H SOCIETY LTD H-26, OLD GOBIND PURA EXT.,DELHI-51 East ACTIVE 4 724-INDL THE JAIN H/L COOP. INDL. (P) SOCIETY LTD. F413 GALI NO. 11, BHAGIRATH VIHAR, DELHI-94 North East ACTIVE THE BAKARWALA COOP. BRICKS KILN (I) 5 24W-INDL SOCIETY LTD. SURERE, NAJAFGARH, N. DELHI-43 West ACTIVE LIQUIDATE 6 24W-NMPS THE BAKARWALA COOP. M/P SOCIETY LTD. West D THE PANDWAL KHOODS COOP N.M.P SOCIETY South LIQUIDATE 7 32-NMPS LTD V.P.O PANDWAL KHOODS, NEW DELHI West D 8 505S-TC The Sikh Coop. Thrift & Credit Society Ltd. 61, Hemkunt Colony, New Delhi- South ACTIVE South 9 124-NMPS THE PALAM COOP N.M.P SOCIETY LTD V&PO, PALAM , NEW DELHI West ACTIVE 211NW- North 10 NMPS BAKAOLI COOL M/P SOCIETY LTD VILLAGE BAKAOLI, DELHI West DEFUNCT NON- 216NE- FUNCTION 11 NMPS THE BABARPUR M/P COOP. SOCIETY LTD. VILLAGE BABARPUR, SHAHDARA, DELHI-32 North East AL Chiragh Delhi Palti Yadram Coop. Thrift & Credit 12 230S-TC Sociey Ltd. 830 Chiragh Delhi,New Delhi-17 South ACTIVE 138NW- North 13 NMPS BUKHTAWAR PUR COOP. -

Your Reputation Deserves Typar Landscape Fabric

YOUR REPUTATION DESERVES TYPAR LANDSCAPE FABRIC. Your reputation can be jeopardized by little to block weeds under decks and in planters, to prevent things. Like weeds. heaving of bricks in patios and walkways, and to mini- Fight back with Typar landscape Fabric, the key to mize erosion. maintenance-free landscaping for your clients. Ask for Typar landscape Fabric for Professionals. Typar is made from rugged polypropylene fabric. It You deserve it. blocks weeds, but is porous enough to let water, air and fertilizer pass through. The result? Healthier soil and plants. Typar leaves all your landscaping projects—and your reputation—looking beautiful longer. There are plenty of other professional uses for Typar: o member of The InterTech Group FOR PROFESSIONALS The Ryan Touch. RYAN Quality equipment for lets you do the job as effectively tings and routine maintenance. So, outstanding results. with less maintenance for as many you'll reduce your downtime while Combine your turf care exper- years as the new Greensaire 24. saving service time between the tise with Ryan turf care equipment, Only with its crank and cam action greens — getting golfers back on and it's a little like working magic do tines go vertically in and out to the course quickly. on your course. Our complete line virtually eliminate side compaction comes with a long history of low- and a ridge around each hole. The Ryan tackles the big jobs, too. maintenance and high performance. result is a smoother putting surface The Ryan Renovaire® is the In fact, the only one who works and better root development. -

Scientific Analysis of 7Th- to 9Th-Century Pottery from Lundenwic

London in the Not-so-Dark Ages Lyn Blackmore Londinium Lundenwic 5th century urn: St Martin-in-the- Fields London Early and Middle Saxon London - coming out of the Dark Ages? 1. Background - Rural settlement c AD 400-650 - City and Lundenwic, early finds 2. The development of Lundenwic - Roman to Saxon London - Burials - Growth and organisation of Lundenwic - Trade and industry - Decline 3. Summing up Late 4th-/5th-century finds Roman riverside wall strengthened AD 388-402 St Bride’s Billingsgate bathhouse Museum of London B538 (M) Eastern cemetery Silver ingot found Western near Tower of London cemetery Early Saxon rural settlement and cemeteries Fish trap , Early Saxon finds St John Clerkenwell Roman western cemetery St Bride’s Billingsgate bathhouse St Martin-in- the-Fields Glass cone beaker and pottery pedestal beaker from the Mitcham cemetery (Clark 1989) 5th- to 6th-century pottery Chaff- and sandstone-tempered wares Emerging kingdoms, changing faith • AD 597 Augustinian mission • AD 604 St Paul’s founded • AD 616-653 East Saxon reversion to paganism • AD 653 Christianity re-established Britain c AD 600 City, near St Paul’s? Saxon finds from outside the City (pre-1983) 7th-century palm cup, The Garrick St Martin-in-the-Fields, Street ring, late found 1722 in a 7th-/early 8th- The Fetter Lane sword sarcophagus burial century pommel, 8th-century © British Museum © British Museum © British Museum Early excavations in Westminster The Savoy, Strand, 1930s From Clark 1989 The Treasury, 1960s Arundel House, Strand, 1970s Lundenwic as understood 1984 From The London Archaeologist From Popular Archaeology Middle Saxon London, as understood c 1990 Vince 1990 Map from Clark 1989 2003 2012 2004 2013 Lundenwic ‘discovered’ 1984 First excavation at Jubilee Hall, 1985 Royal Opera House Since then over 80 excavations and watching briefs carried out Early and Middle Saxon London - coming out of the Dark Ages? 1. -

(Died 704) Ælfric, Abbot of Eynsham

People ADALBERO, BISHOP OF LAON (FRANCE; 977-1030) Adalbero was very involved in the politics of the end of Carolingian dynasty in Western Frankia and its replacement by the Capetians, with the accession of Hugh Capet as king in 987. He was one of the writers who expressed the concept of society divided between the three orders. ADOMNÁN , ABBOT OF IONA (DIED 704) Adomnán was the ninth abbot of the monastery of Iona, founded on the island of that name in the Hebrides by Columba. He is particularly noted by Bede in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People for having promoted the Roman dating of Easter. His best-known work is his Life of St Columba. ÆLFRIC, ABBOT OF EYNSHAM (1005-C. 1010) Ælfric joined the monastery of Cerne Abbas (Dorset) around 987. He may have been in charge of the school there, and he certainly produced a series of writings, including works in Old English, principally homilies for reading and preaching and lives of saints, and a grammar of Latin written in Old English. In 1005, he became the first abbot of the reformed abbey of Eynsham near Oxford, where he died around 1010. ÆTHELEBERHT I, KING OF KENT (DIED 616) Ætheleberht, who had married the Christian, Frankish princess, Bertha, some while before, welcomed the mission of St Augustine when it arrived in Kent in 597. He permitted the conversion of his subjects, and was himself converted, perhaps soon after Augustine's arrival. Bede identified him as one of the seven overlords of southern England (Bede, Eccl. History, II.15) and attributed to him a code of laws 'in the manner of the Romans', which is extant. -

Lives of the British Saints

LIVES OF THE BRITISH SAINTS Vladimir Moss Copyright: Vladimir Moss, 2009 1. SAINTS ACCA AND ALCMUND, BISHOPS OF HEXHAM ......................5 2. SAINT ADRIAN, ABBOT OF CANTERBURY...............................................8 3. SAINT ADRIAN, HIEROMARTYR BISHOP OF MAY and those with him ....................................................................................................................................9 4. SAINT AIDAN, BISHOP OF LINDISFARNE...............................................11 5. SAINT ALBAN, PROTOMARTYR OF BRITAIN.........................................16 6. SAINT ALCMUND, MARTYR-KING OF NORTHUMBRIA ....................20 7. SAINT ALDHELM, BISHOP OF SHERBORNE...........................................21 8. SAINT ALFRED, MARTYR-PRINCE OF ENGLAND ................................27 9. SAINT ALPHEGE, HIEROMARTYR ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY ..................................................................................................................................30 10. SAINT ALPHEGE “THE BALD”, BISHOP OF WINCHESTER...............41 11. SAINT ASAPH, BISHOP OF ST. ASAPH’S ................................................42 12. SAINTS AUGUSTINE, LAURENCE, MELLITUS, JUSTUS, HONORIUS AND DEUSDEDIT, ARCHBISHOPS OF CANTERBURY ..............................43 13. SAINTS BALDRED AND BALDRED, MONKS OF BASS ROCK ...........54 14. SAINT BATHILD, QUEEN OF FRANCE....................................................55 15. SAINT BEDE “THE VENERABLE” OF JARROW .....................................57 16. SAINT BENIGNUS (BEONNA) -

Mgcsa Classified Ads

MGCSA CLASSIFIED ADS FOR SALE FOR SALE FOR SALE FOR SALE 15 hp Motor w/Berkeley Used • 1983 Toro Greensmaster 3 Pump (3-phased) TORO 474 1" BRASS Olathe Fairway triplex riding greensmower. 14 Used 2 years QUICK COUPLER VALVES Core Pulverizer h.p. Kohler. Very good Reel stock, $700 or Best Offer with standard cover. (2) 6" Clay Valves 8 blade reels, 4 bolt adjust. $900 l Contact: Requires l A" valve key. JOHN MONSON Contact: Dan or Greg • 1986 National 84" Triplex $15.00 each. Long Prairie, CC St. Cloud Country Club mower, 16 h.p. Kohler engine, ex- Contact: cellent condition $800 DAVID WOOD Oxbow CC (320) 732-3696 • 1983 Columbia Utility Cart (evenings) (320) 253-1331 with box $300 (701) 588-4266 • 1987 Columbia Golf Cart. $400 • 1988 Horvick 20" Trailer FOR SALE Sprayer with 70 gal. tank with FOR SALE TfeeJet 744 electric controls. $800 FOR SALE • 40 Toro VT3 Cushman Trucksters 1991 Controllers $400 This equipment is for sale from Toro Fairway Aerator 1966 Runabout • 1 LTC Controller . .$600 the Fargo Park District. All $ - Model 9500 Great condition... 1,000 equipment is sold as is with no All controllers include steel Used one season. warranty. All equipment can be 1988 Dump 22HP w/Rops pedestal and control panel. Price is negotiable. Contact: viewed at Edgewood Golf Course $3,500 TOM FISCHER Contact: KEVIN CLUNIS Maintenance Shop between the Contact: RICK LaPORTE Edinburgh USA St. Croix National Golf Club hours of 7:00 a.m. and 3:30 p.m. Phone 235-8234 for appoint- Tartan Park (612) 424-8756 (715) 247-4260 ment. -

Listing in Dewey Decimal Order Knox County Schools Library Services

Listing in Dewey Decimal Order Knox County Schools Library Services Gift Criteria We recommend that you accept gift books based on these criteria Our office will only catalog gift books that meet these criteria General Dewey Topic Recommendation Subdivision Computer Science Accept nothing older than 10 years, 5 years is better 000s General Works Accept nothing older than 10 years, 5 years is better Information Accept nothing older than 10 years, 5 years is better Philosophy Accept nothing older than 10 years 100s Psychology Accept nothing older than 10 years Accept on the condition of the item, accept no 200s Religion propaganda 300-309 Social Sciences Accept nothing older than 10 years 310s General Statistics Accept nothing older than 5 years 320s Political Science Accept nothing older than 10 years 330s Economics Accept nothing older than 10 years 340s Law Accept nothing older than 10 years 350s Public Administration Accept nothing older than 10 years 360s Social Services Accept nothing older than 10 years 370s Education Accept nothing older than 10 years Commerce Accept nothing older than 10 years 380s Communications Accept nothing older than 10 years Transportation Accept nothing older than 10 years Customs Accept on the need and condition of the item 390s Etiquette Accept on the need and condition of the item Folklore Accept on the need and condition of the item 400s Language Accept on the need and condition of the item 500-509 Natural Science Accept nothing older than 10 years 510s Mathematics Accept nothing older than 10 years -

Sterile Distal Radius Kit Surgical Technique Image Intensifier Control

For Fragment-Specifi c Fracture Fixation Using the Variable Angle LCP® Two-Column Volar Distal Radius Plate 2.4 With Variable Angle Locking Technology Sterile Distal Radius Kit Surgical Technique Image intensifier control Warning This description alone does not provide sufficient background for direct use of DePuy Synthes products. Instruction by a surgeon experienced in handling these products is highly recommended. Processing, Reprocessing, Care and Maintenance For general guidelines, function control and dismantling of multi-part instruments, as well as processing guidelines for implants, please contact your local sales representative or refer to: http://emea.depuysynthes.com/hcp/reprocessing-care-maintenance For general information about reprocessing, care and maintenance of Synthes reusable devices, instrument trays and cases, as well as processing of Synthes non-sterile implants, please consult the Important Information leaflet (SE_023827) or refer to: http://emea.depuysynthes.com/hcp/reprocessing-care-maintenance Table of Contents Introduction Indications 3 Sterile Kit Variations and Added Instruments 4 Distal Radius Sterile Kit Key Steps 6 Sterile Tube Packaging 7 AO Principles 8 Clinical Cases 9 Surgical Technique Approach 10 Implantation Steps 11 Postoperative Treatment and Implant Removal 21 Product Information 22 MRI Information 28 Bibliography 29 Sterile Distal Radius Kit Surgical Technique DePuy Synthes 1 2 DePuy Synthes Sterile Distal Radius Kit Surgical Technique Indications Variable Angle LCP® Two-Column Volar Distal Radius Plates 2.4 are indicated for the fixation of intra- and extra-articular fractures and osteotomies of the distal radius. Sterile Distal Radius Kit Surgical Technique DePuy Synthes 3 Sterile Kit Variations and Added Instruments Variable Angle LCP® Volar and Dorsal Distal Core sterile kits Radius Plates 2.4. -

Trade and Exchange in Anglo-Saxon Wessex, C Ad 600–780

Medieval Archaeology, 60/1, 2016 Trade and Exchange in Anglo-Saxon Wessex, c ad 600–780 By MICHAEL D COSTEN1 and NICHOLAS P COSTEN2 THIS PAPER ASSESSES the provenance and general distribution of coins of the period c ad 600–780 found in the west of Anglo-Saxon Wessex. It shows that the distribution of coin finds is not a function of the habits of metal detectorists, but a reflection of the real pattern of losses. In the second part of the paper, an analysis of the observed distributions is presented which reveals that the bulk of trade, of which the coins are a sign, was carried on through local ports and that foreign trade was not mediated through Hamwic, but came directly from the Continent. The distribution of coin finds also suggests an important export trade, probably in wool and woollen goods, controlled from major local centres. There are also hints of a potentially older trade system in which hillforts and other open sites were important. INTRODUCTION Discussion of trade and exchange in the middle Anglo-Saxon period has reached an advanced stage, and the progress in understanding the possible reach and consequences of recent discoveries has transformed our view of Anglo-Saxon society in the period ad 600–800. Most of the research has focused upon the eastern side of Britain, in particular upon discoveries in East Anglia, Lincolnshire and the south-east. The stage was really set in 1982 when Richard Hodges put forward his model of the growth of exchange and trade among the emerging 7th-century Anglo-Saxon kingdoms; he developed the thesis that the trade which took place was concentrated in particular localities which he labelled ‘emporia’.3 It seemed that there might be one of these central places for each of the newly forming Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, or at least the dominant ones.