LONDON and ITS MINT C.880–1066: a PRELIMINARY SURVEY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London's Soap Industry and the Development of Global Ghost Acres

London’s Soap Industry and the Development of Global Ghost Acres in the Nineteenth Century John Knight won a prize medal at the Great Exhibition in 1851 for his soaps, which included an ‘excellent Primrose or Pale-yellow-soap, made with tallow, American rosin, and soda’.1 In the decades that followed the prize, John Knight’s Royal Primrose Soap emerged as one of the United Kingdom’s leading laundry soap brands. In 1880, the firm moved down the Thames from Wapping in East London to a significantly larger factory in West Ham’s Silvertown district.2 The new soap works was capable of producing between two hundred and three hundred tons of soap per week, along with a considerable number of candles, and extracting oil from four hundred tons of cotton seeds.3 To put this quantity of soap into context, the factory could manufacture more soap in a year than the whole of London produced in 1832.4 The prize and relocation together represented the industrial and commercial triumph of this nineteenth-century family business. A complimentary article from 1888, argued the firm’s success rested on John Knights’ commitment ‘to make nothing but the very best articles, to sell them at the very lowest possible prices, and on no account to trade beyond his means’.5 The publication further explained that before the 1830s, soap ‘was dark in colour, and the 1 Charles Wentworth Dilke, Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, 1851: Catalogue of a Collection of Works On, Or Having Reference To, the Exhibition of 1851, 1852, 614. -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

The Alfred Jewel, an Historical Essay, Earle John, 1901

F — — ALFEED JEWEL. tAv£S 3JD-6/. THE — THJ!; ALFIiED JEWEL. TIMES. TO THE EDITOR OF THE TO THE EDITOR OF THE TIMES. have been treading it is oir -Where so many angels Sir, —Mr. Elworthy would appear to be incapable of hnmble student to ventnre in. &tm, apprehending " perhaps rmwise for a my particular predicament in this Five another guess at the \"^^he worth whUe to make o'clock tea" controversy over the " Al frcd Jewel " jewel. which simply is that the traces of Oriental truth about the Alfred influence to be Musgrave, a Fellow of the Royal observed in its form and decoration support Professor Since 1698, when Dr. the the first notice of the jewel m Earle's contention that it was meant to be worn on a Society, published Tnmsactions"(No 247) It has been helmet. Surely this very humble suggestion is deserving f< Sophi-l " have been (1) an amulet of some consideration, especially as the " Alfred Jewel en^.ested that the jewel may a pendant to a chaan or was fastened to whatever it was attached in the same Musgrave's suggestion) ; (2) mT " " " of a roller for a M.S. ; manner as the two parts—the knop" and the flower • or head (3) an umbilicus, collar book-pomter (5) the head of a ; —of the Mo(n)gol torn were, and are, fastened together. the' top of a stilus ; U) sceptre standard; (7) the head of a ; After Professor Earle's suggestion of the purpose of 6 the top of a xs tbe " for .Alfred's helmet. -

Constructing the Seventh Century

COLLÈGE DE FRANCE – CNRS CENTRE DE RECHERCHE D’HISTOIRE ET CIVILISATION DE BYZANCE TRAVAUX ET MÉMOIRES 17 constructing the seventh century edited by Constantin Zuckerman Ouvrage publié avec le concours de la fondation Ebersolt du Collège de France et de l’université Paris-Sorbonne Association des Amis du Centre d’Histoire et Civilisation de Byzance 52, rue du Cardinal-Lemoine – 75005 Paris 2013 PREFACE by Constantin Zuckerman The title of this volume could be misleading. “Constructing the 7th century” by no means implies an intellectual construction. It should rather recall the image of a construction site with its scaffolding and piles of bricks, and with its plentiful uncovered pits. As on the building site of a medieval cathedral, every worker lays his pavement or polishes up his column knowing that one day a majestic edifice will rise and that it will be as accomplished and solid as is the least element of its structure. The reader can imagine the edifice as he reads through the articles collected under this cover, but in this age when syntheses abound it was not the editor’s aim to develop another one. The contributions to the volume are regrouped in five sections, some more united than the others. The first section is the most tightly knit presenting the results of a collaborative project coordinated by Vincent Déroche. It explores the different versions of a “many shaped” polemical treatise (Dialogica polymorpha antiiudaica) preserved—and edited here—in Greek and Slavonic. Anti-Jewish polemics flourished in the seventh century for a reason. In the centuries-long debate opposing the “New” and the “Old” Israel, the latter’s rejection by God was grounded in an irrefutable empirical proof: God had expelled the “Old” Israel from its promised land and given it to the “New.” In the first half of the seventh century, however, this reasoning was shattered, first by the Persian conquest of the Holy Land, which could be viewed as a passing trial, and then by the Arab conquest, which appeared to last. -

How Could Phenological Records from the Chinese Poems of the Tang and Song Dynasties

https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-2020-122 Preprint. Discussion started: 28 September 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. How could phenological records from the Chinese poems of the Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1260 AD) be reliable evidence of past climate changes? Yachen Liu1, Xiuqi Fang2, Junhu Dai3, Huanjiong Wang3, Zexing Tao3 5 1School of Biological and Environmental Engineering, Xi’an University, Xi’an, 710065, China 2Faculty of Geographical Science, Key Laboratory of Environment Change and Natural Disaster MOE, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China 3Key Laboratory of Land Surface Pattern and Simulation, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Science (CAS), Beijing, 100101, China 10 Correspondence to: Zexing Tao ([email protected]) Abstract. Phenological records in historical documents have been proved to be of unique value for reconstructing past climate changes. As a literary genre, poetry reached its peak period in the Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1260 AD) in China, which could provide abundant phenological records in this period when lacking phenological observations. However, the reliability of phenological records from 15 poems as well as their processing methods remains to be comprehensively summarized and discussed. In this paper, after introducing the certainties and uncertainties of phenological information in poems, the key processing steps and methods for deriving phenological records from poems and using them in past climate change studies were discussed: -

MEDIEVAL DAMASCUS Arabic Book Culture, Library Culture and Reading Culture Is Significantly Enriched.’ Li Guo, University of Notre Dame and MEDIEVAL

PLURALITY KONRAD HIRSCHLER ‘This is a tour de force of ferocious codex dissection, relentless bibliographical probing and imaginative reconstructive storytelling. Our knowledge of medieval MEDIEVAL DAMASCUS DAMASCUS MEDIEVAL Arabic book culture, library culture and reading culture is significantly enriched.’ Li Guo, University of Notre Dame AND MEDIEVAL The first documented insight into the content and DIVERSITY structure of a large-scale medieval Arabic library The written text was a pervasive feature of cultural practices in the medieval Middle East. At the heart of book circulation stood libraries that experienced a rapid expansion from the DAMASCUS twelfth century onwards. While the existence of these libraries is well known, our knowledge of their content and structure has been very limited as hardly any medieval Arabic catalogues have been preserved. This book discusses the largest and earliest medieval library of the PLURALITY AND Middle East for which we have documentation – the Ashrafiya library in the very centre of IN AN Damascus – and edits its catalogue. The catalogue shows that even book collections attached to Sunni religious institutions could hold very diverse titles, including Muʿtazilite theology, DIVERSITY IN AN Shiʿite prayers, medical handbooks, manuals for traders, stories from the 1001 Nights and texts extolling wine consumption. ARABIC LIBRARY ARABIC LIBRARY Listing over two thousand books the Ashrafiya catalogue is essential reading for anybody interested in the cultural and intellectual history of Arabic societies. -

The History of London

The History of London STUDENT A The Romans came to England in ____________ ( when? ) and built the town of Londinium on the River Thames. Londinium soon grew bigger and bigger. Ships came there from all over Europe and the Romans built _____________ ( what? ) from Londinium to other parts of Britain. By the year 400, there were 50,000 people in the city. Soon after 400 the Romans left, and we do not know much about London between 400 and 1000. In __________ (when? ) William the Conqueror came to England from Normandy in France. William became King of England and lived in ___________ ( where? ). But William was afraid of the people of London, so he built a big building for himself – the White Tower. Now it is part of the Tower of London and many ____________ ( who? ) visit it to see the Crown Jewels – the Queen’s gold and diamonds. London continued to grow. By 1600 there were ______________ ( how many? ) people in the city and by 1830 the population was one and a half million people. The railways came and there were ___________ ( what? ) all over the city. This was the London that Dickens New and wrote about – a city of very rich and very poor people. At the start of the 20th century, _____________ ( how many? ) people lived in London. Today the population of Greater London is seven and a half million. ______________ ( how many ?) tourists visit London every year and you can her 300 different languages on London’s streets! ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- STUDENT B The Romans came to England in AD43 and built the town of Londinium ____________ (where? ). -

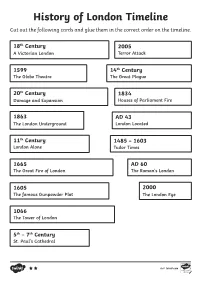

History of London Timeline Cut out the Following Cards and Glue Them in the Correct Order on the Timeline

History of London Timeline Cut out the following cards and glue them in the correct order on the timeline. 18th Century 2005 A Victorian London Terror Attack 1599 14th Century The Globe Theatre The Great Plague 20th Century 1834 Damage and Expansion Houses of Parliament Fire 1863 AD 43 The London Underground London Located 11th Century 1485 – 1603 London Alone Tudor Times 1665 AD 60 The Great Fire of London The Roman’s London 1605 2000 The famous Gunpowder Plot The London Eye 1066 The Tower of London 5th – 7th Century St. Paul’s Cathedral visit twinkl.com This famous theatre is where many Unfortunately, there was lots of damage to of William Shakespeare’s plays were London due to bombings during the Second performed. However, in 1613, it was World War including to St. Paul’s Cathedral. burnt down by a staged cannon fire in London once again expanded and many one of his plays. Today, a new 1990s big department stores such as Harrods and Globe Theatre, close to the original Selfridges were built. building, still holds performances of Shakespeare’s plays. 200 years after Guy Fawkes tried to Due to its trading links, Britain and London blow up the Houses of Parliament, became very powerful with goods from all over an accidental fire spread through the world being imported. the main building leaving only Westminster Hall undamaged. The th During the 18 century and Queen Victoria’s replacement was built ten years reign, the population of London expanded and later and still remains there today. many of the buildings we still see in London today were built during the Victorian times. -

London: Biography of a City

1 SYLLABUS LONDON: BIOGRAPHY OF A CITY Instructor: Dr Keith Surridge Contact Hrs: 45 Language of Instruction: English COURSE DESCRIPTION This course traces the growth and development of the city of London from its founding by the Romans to the end of the twentieth-century, and encompasses nearly 2000 years of history. Beginning with the city’s foundation by the Romans, the course will look at how London developed following the end of the Roman Empire, through its abandonment and revival under the Anglo-Saxons, its growing importance as a manufacturing and trading centre during the long medieval period; the changes wrought by the Reformation and fire during the reigns of the Tudors and Stuarts; the city’s massive growth during the eighteenth and nineteenth-centuries; and lastly, the effects of war, the loss of empire, and the post-war world during the twentieth-century. This course will outline the city’s expansion and its increasing significance in first England’s, and then Britain’s affairs. The themes of economic, social, cultural, political, military and religious life will be considered throughout. To complement the class lectures and discussions field trips will be made almost every week. COURSE OBJECTIVES By the end of the course students are expected to: • Know the main social and political aspects and chronology of London’s history. • Have developed an understanding of how London, its people and government have responded to both internal and external pressures. • Have demonstrated knowledge, analytical skills, and communication through essays, multiple-choice tests, an exam and a presentation. INSTRUCTIONAL METHODOLOGY The course will be taught through informal lectures/seminars during which students are invited to comment on, debate and discuss any aspects of the general lecture as I proceed. -

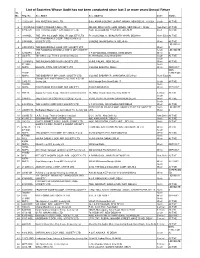

List of Societies Not Audited for Last 3 Years Or More/Annual Return

List of Societies Whose Audit has not been conducted since last 3 or more years/Annual Return Sr. No. Reg. No. Soc. Name Soc. Address Zone Status 1 1232S-GH NAV NIKETAN CGHS LTD B-83, AMAR COLONY, LAJPAT NAGAR, NEW DELHI : 110 024 South ACTIVE 2 1451ND-GH PREETI PRISHAD CGHS LTD. DB-84E, DDA FLATS, HARI NAGAR, NEW DELHI: 110 063 New Delhi ACTIVE 3 875E-GH NAV TARANG COOP. G/H SOCIETY LTD H-26, OLD GOBIND PURA EXT.,DELHI-51 East ACTIVE 4 724-INDL THE JAIN H/L COOP. INDL. (P) SOCIETY LTD. F413 GALI NO. 11, BHAGIRATH VIHAR, DELHI-94 North East ACTIVE THE BAKARWALA COOP. BRICKS KILN (I) 5 24W-INDL SOCIETY LTD. SURERE, NAJAFGARH, N. DELHI-43 West ACTIVE LIQUIDATE 6 24W-NMPS THE BAKARWALA COOP. M/P SOCIETY LTD. West D THE PANDWAL KHOODS COOP N.M.P SOCIETY South LIQUIDATE 7 32-NMPS LTD V.P.O PANDWAL KHOODS, NEW DELHI West D 8 505S-TC The Sikh Coop. Thrift & Credit Society Ltd. 61, Hemkunt Colony, New Delhi- South ACTIVE South 9 124-NMPS THE PALAM COOP N.M.P SOCIETY LTD V&PO, PALAM , NEW DELHI West ACTIVE 211NW- North 10 NMPS BAKAOLI COOL M/P SOCIETY LTD VILLAGE BAKAOLI, DELHI West DEFUNCT NON- 216NE- FUNCTION 11 NMPS THE BABARPUR M/P COOP. SOCIETY LTD. VILLAGE BABARPUR, SHAHDARA, DELHI-32 North East AL Chiragh Delhi Palti Yadram Coop. Thrift & Credit 12 230S-TC Sociey Ltd. 830 Chiragh Delhi,New Delhi-17 South ACTIVE 138NW- North 13 NMPS BUKHTAWAR PUR COOP. -

Your Reputation Deserves Typar Landscape Fabric

YOUR REPUTATION DESERVES TYPAR LANDSCAPE FABRIC. Your reputation can be jeopardized by little to block weeds under decks and in planters, to prevent things. Like weeds. heaving of bricks in patios and walkways, and to mini- Fight back with Typar landscape Fabric, the key to mize erosion. maintenance-free landscaping for your clients. Ask for Typar landscape Fabric for Professionals. Typar is made from rugged polypropylene fabric. It You deserve it. blocks weeds, but is porous enough to let water, air and fertilizer pass through. The result? Healthier soil and plants. Typar leaves all your landscaping projects—and your reputation—looking beautiful longer. There are plenty of other professional uses for Typar: o member of The InterTech Group FOR PROFESSIONALS The Ryan Touch. RYAN Quality equipment for lets you do the job as effectively tings and routine maintenance. So, outstanding results. with less maintenance for as many you'll reduce your downtime while Combine your turf care exper- years as the new Greensaire 24. saving service time between the tise with Ryan turf care equipment, Only with its crank and cam action greens — getting golfers back on and it's a little like working magic do tines go vertically in and out to the course quickly. on your course. Our complete line virtually eliminate side compaction comes with a long history of low- and a ridge around each hole. The Ryan tackles the big jobs, too. maintenance and high performance. result is a smoother putting surface The Ryan Renovaire® is the In fact, the only one who works and better root development. -

The Role of Religious Institutions in Constructing Minorities’ Religious

The Role of Religious Institutions in Constructing Minorities’ Religious Identity Muslim Minorities in non-Muslim Society Case Study of The Manchester Islamic Centre A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of PhD Sociology in the Faculty of Humanities, School of Social Sciences, Department of Sociology. 2014 Ghalia Sarmani 1 Contents…………………………………………………………………………................2 Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………………9 Declaration of Authenticity……………………………………………………………...10 Copyright Statement……………………………………………………………………..11 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………….12 Chapter One: Themes and Issues……………………………………………………….13 1.1 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………...13 1.2 Summary of Chapters …………………………………………………………………15 Chapter Two: History of Muslim Presence in Britain from Early Times until the Present………………………………………………………………………………….....20 2.1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………....20 2.2 Earliest Period of Muslim Migration to Britain ………………………………………22 2.2.1 Muslim Settlement up to the First World War…………………………………..24 2.2.2 Muslim Migration to Britain after the Second World War……………………...26 2.3 Muslim Arab Settlement in Manchester……………………………………………….27 2.4 Patterns of Muslim Migration ………………………………………………………...29 2.5 Muslim Migration Factors……………………………………………………………..29 2.6 Statistical Summary of Muslims in Britain……………………………………………35 2.6.1 Muslim Population Estimates via Census....………………………………….....35 2.6.2 Christianity as the Main Religion in Britain...…………………………………..38 2.6.3 Ethnic Groups, England and