London's Soap Industry and the Development of Global Ghost Acres

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indonesia's Moratorium on Palm Oil Expansion from Natural Forests: Economy-Wide Impacts and the Role of International Transfer

Indonesia’s Moratorium on Palm Oil Expansion from Natural Forests: Economy-Wide Impacts and the Role of International Transfers Arief A. Yusuf,Elizabeth L. Roos, and Jonathan M. Horridge∗ Indonesia has introduced a moratorium on the conversion of natural forests to land used for palm oil production. Using a dynamic, bottom-up, interregional computable general equilibrium model of the Indonesian economy, we assess several scenarios of the moratorium and discuss its impacts on the domestic economy as well as on regional economies within Indonesia. We find the moratorium reduces Indonesian economic growth and other macroeconomic indicators, but international transfers can more than compensate the welfare losses. The impacts also vary across regions. Sumatra, which is highly dependent on palm oil and is home to forests that no longer have a high carbon stock, receives fewer transfers and suffers the greatest economic loss. Kalimantan, which is relatively less dependent on palm oil and has forests with a relatively high carbon stock, receives more transfers and gets greater benefit. This implies that additional policy measures anticipating the unbalanced impacts of the moratorium are required if the trade-off between conservation and reducing interregional economic disparity is to be reconciled. Keywords: carbon emissions, computable general equilibrium, Indonesia, palm oil JEL codes: R10, R11, R13 I. Introduction The United Nations Reduction of Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) program seeks to reduce carbon emissions resulting from deforestation and enhance carbon stocks in forests, while also contributing to national sustainable development (UN-REDD 2015). REDD supports developing countries in their efforts to mitigate climate change through the implementation of several activities. -

Non-Timber Forest Products

Agrodok 39 Non-timber forest products the value of wild plants Tinde van Andel This publication is sponsored by: ICCO, SNV and Tropenbos International © Agromisa Foundation and CTA, Wageningen, 2006. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photocopy, microfilm or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. First edition: 2006 Author: Tinde van Andel Illustrator: Bertha Valois V. Design: Eva Kok Translation: Ninette de Zylva (editing) Printed by: Digigrafi, Wageningen, the Netherlands ISBN Agromisa: 90-8573-027-9 ISBN CTA: 92-9081-327-X Foreword Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) are wild plant and animal pro- ducts harvested from forests, such as wild fruits, vegetables, nuts, edi- ble roots, honey, palm leaves, medicinal plants, poisons and bush meat. Millions of people – especially those living in rural areas in de- veloping countries – collect these products daily, and many regard selling them as a means of earning a living. This Agrodok presents an overview of the major commercial wild plant products from Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific. It explains their significance in traditional health care, social and ritual values, and forest conservation. It is designed to serve as a useful source of basic information for local forest dependent communities, especially those who harvest, process and market these products. We also hope that this Agrodok will help arouse the awareness of the potential of NTFPs among development organisations, local NGOs, government officials at local and regional level, and extension workers assisting local communities. Case studies from Cameroon, Ethiopia, Central and South Africa, the Pacific, Colombia and Suriname have been used to help illustrate the various important aspects of commercial NTFP harvesting. -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

Current Knowledge on Interspecific Hybrid Palm Oils As Food and Food

foods Review Current Knowledge on Interspecific Hybrid Palm Oils as Food and Food Ingredient Massimo Mozzon , Roberta Foligni * and Cinzia Mannozzi * Department of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Sciences, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Via Brecce Bianche 10, 60131 Ancona, Italy; m.mozzon@staff.univpm.it * Correspondence: r.foligni@staff.univpm.it (R.F.); c.mannozzi@staff.univpm.it (C.M.); Tel.: +39-071-220-4010 (R.F.); +39-071-220-4014 (C.M.) Received: 6 April 2020; Accepted: 10 May 2020; Published: 14 May 2020 Abstract: The consumers’ opinion concerning conventional palm (Elaeis guineensis) oil is negatively affected by environmental and nutritional issues. However, oils extracted from drupes of interspecific hybrids Elaeis oleifera E. guineensis are getting more and more interest, due to their chemical and × nutritional properties. Unsaturated fatty acids (oleic and linoleic) are the most abundant constituents (60%–80% of total fatty acids) of hybrid palm oil (HPO) and are mainly acylated in position sn-2 of the glycerol backbone. Carotenes and tocotrienols are the most interesting components of the unsaponifiable matter, even if their amount in crude oils varies greatly. The Codex Committee on Fats and Oils recently provided HPO the “dignity” of codified fat substance for human consumption and defined the physical and chemical parameters for genuine crude oils. However, only few researches have been conducted to date on the functional and technological properties of HPO, thus limiting its utilization in food industry. Recent studies on the nutritional effects of HPO softened the initial enthusiasm about the “tropical equivalent of olive oil”, suggesting that the overconsumption of HPO in the most-consumed processed foods should be carefully monitored. -

The History of London

The History of London STUDENT A The Romans came to England in ____________ ( when? ) and built the town of Londinium on the River Thames. Londinium soon grew bigger and bigger. Ships came there from all over Europe and the Romans built _____________ ( what? ) from Londinium to other parts of Britain. By the year 400, there were 50,000 people in the city. Soon after 400 the Romans left, and we do not know much about London between 400 and 1000. In __________ (when? ) William the Conqueror came to England from Normandy in France. William became King of England and lived in ___________ ( where? ). But William was afraid of the people of London, so he built a big building for himself – the White Tower. Now it is part of the Tower of London and many ____________ ( who? ) visit it to see the Crown Jewels – the Queen’s gold and diamonds. London continued to grow. By 1600 there were ______________ ( how many? ) people in the city and by 1830 the population was one and a half million people. The railways came and there were ___________ ( what? ) all over the city. This was the London that Dickens New and wrote about – a city of very rich and very poor people. At the start of the 20th century, _____________ ( how many? ) people lived in London. Today the population of Greater London is seven and a half million. ______________ ( how many ?) tourists visit London every year and you can her 300 different languages on London’s streets! ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- STUDENT B The Romans came to England in AD43 and built the town of Londinium ____________ (where? ). -

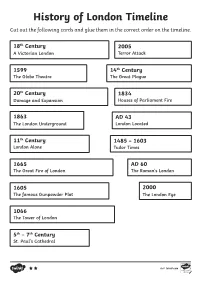

History of London Timeline Cut out the Following Cards and Glue Them in the Correct Order on the Timeline

History of London Timeline Cut out the following cards and glue them in the correct order on the timeline. 18th Century 2005 A Victorian London Terror Attack 1599 14th Century The Globe Theatre The Great Plague 20th Century 1834 Damage and Expansion Houses of Parliament Fire 1863 AD 43 The London Underground London Located 11th Century 1485 – 1603 London Alone Tudor Times 1665 AD 60 The Great Fire of London The Roman’s London 1605 2000 The famous Gunpowder Plot The London Eye 1066 The Tower of London 5th – 7th Century St. Paul’s Cathedral visit twinkl.com This famous theatre is where many Unfortunately, there was lots of damage to of William Shakespeare’s plays were London due to bombings during the Second performed. However, in 1613, it was World War including to St. Paul’s Cathedral. burnt down by a staged cannon fire in London once again expanded and many one of his plays. Today, a new 1990s big department stores such as Harrods and Globe Theatre, close to the original Selfridges were built. building, still holds performances of Shakespeare’s plays. 200 years after Guy Fawkes tried to Due to its trading links, Britain and London blow up the Houses of Parliament, became very powerful with goods from all over an accidental fire spread through the world being imported. the main building leaving only Westminster Hall undamaged. The th During the 18 century and Queen Victoria’s replacement was built ten years reign, the population of London expanded and later and still remains there today. many of the buildings we still see in London today were built during the Victorian times. -

Lyon Playfair: Chemist and Commissioner, 1818–1858

Science Museum Group Journal Lyon Playfair: chemist and commissioner, 1818–1858 Journal ISSN number: 2054-5770 This article was written by Ian Blatchford 05-04-2021 Cite as 10.15180; 211504 Research Lyon Playfair: chemist and commissioner, 1818–1858 Published in Spring 2021, Issue 15 Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211504 Abstract Lyon Playfair was a multi-talented man: a scientist, administrator and politician whose life and influence deserve further research. This article concentrates on the period between 1818 and 1858, from Playfair’s birth to his appointment as Professor of Chemistry at the University of Edinburgh. His biographer (Sir Thomas Wemyss Reid) described his life as a ‘story not of adventure, but work’ and yet his record was one of energetic enterprise that had considerable impact. He was a rising star in the then fashionable world of chemistry, a favoured student of the founder of organic chemistry, Justus Liebig, and a central figure in the promotion of new ideas in agricultural science.[1] A career in science and the state saw him connected to the leading figures of both, and he played a crucial role in the conceptual and financial success of the Great Exhibition, and its legacy. His brilliance has been overshadowed by the extrovert Henry Cole, and yet Playfair was essential to the major educational reforms of their time. Component DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211504/001 Keywords Lyon Playfair, chemistry, politics, biography, University of Edinburgh, Justus Liebig, Great Exhibition Introduction [2] Playfair was a versatile man: scientist, administrator and politician. This article concentrates on the period between 1818 and 1858, from his birth to his appointment as Professor of Chemistry at Edinburgh. -

Endrés As an Illustrator

chapter∑ 4 Endrés as an illustrator Franco Pupulin According to the definition provided by Botanical Gardens Conservation International, “the main goal of botanical illustration is not art, but scientific accuracy”. A botanical illustrator must portray a plant with enough precision and detail for it to be recognized and distinguished from another species, and the need for exactness is what fundamentally differentiates botanical illustration from more general flower painting. If, traditionally, the best botanical illustrators try to understand the structure of plants and to communicate that in an aesthetically pleasing manner, combining science and art, this was probably not the concern of Auguste R. Endrés when preparing his orchid illustrations in Costa Rica. He had, however, a remarkable artistic talent, and his activity was influenced by the great tradition of orchid painting. The results of his illustration work not only attain the highest levels of botanical accuracy, but set a new standard in orchid art and science. As we will see, only because his masterful plates were lost among the forgotten materials of Reichenbach’s venomous legacy, was Endrés’ work prevented from having a major influence on the discipline of botanical illustration. The golden age of botanical illustration in Europe Beginning in the 17th century, and more frequently during the Enlightenment of the 18th Century, European artists and scientists undertook major projects for collecting and cataloguing nature in its amazing variety. 1613 saw the publication of the Hortus Eystettensis1 (literally the Garden of Eichstätt), a landmark work in the history of botanical art and one of the greatest botanical sets ever created. -

London: Biography of a City

1 SYLLABUS LONDON: BIOGRAPHY OF A CITY Instructor: Dr Keith Surridge Contact Hrs: 45 Language of Instruction: English COURSE DESCRIPTION This course traces the growth and development of the city of London from its founding by the Romans to the end of the twentieth-century, and encompasses nearly 2000 years of history. Beginning with the city’s foundation by the Romans, the course will look at how London developed following the end of the Roman Empire, through its abandonment and revival under the Anglo-Saxons, its growing importance as a manufacturing and trading centre during the long medieval period; the changes wrought by the Reformation and fire during the reigns of the Tudors and Stuarts; the city’s massive growth during the eighteenth and nineteenth-centuries; and lastly, the effects of war, the loss of empire, and the post-war world during the twentieth-century. This course will outline the city’s expansion and its increasing significance in first England’s, and then Britain’s affairs. The themes of economic, social, cultural, political, military and religious life will be considered throughout. To complement the class lectures and discussions field trips will be made almost every week. COURSE OBJECTIVES By the end of the course students are expected to: • Know the main social and political aspects and chronology of London’s history. • Have developed an understanding of how London, its people and government have responded to both internal and external pressures. • Have demonstrated knowledge, analytical skills, and communication through essays, multiple-choice tests, an exam and a presentation. INSTRUCTIONAL METHODOLOGY The course will be taught through informal lectures/seminars during which students are invited to comment on, debate and discuss any aspects of the general lecture as I proceed. -

Converting Waste Oil Palm Trees Into a Resource R O G R a M M E P N V I R O N M E N T E

w w w . u n ep. o r g United Nations Environment Programme P.O. Box 30552 Nairobi, 00100 Kenya Tel: (254 20) 7621234 Fax: (254 20) 7623927 E-mail: [email protected] web: www.unep.org CONVERTING WASTE OIL PALM TREES INTO A ESOURCE R ROGRAMME P NVIRONMENT E ATIONS N NITED U Copyright © United Nations Environment Programme, 2012 This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educa- tional or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP would appreciate receiv- ing a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations Environment Programme. Disclaimer The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Na- tions Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundar- ies. Moreover, the views expressed do not necessarily represent the decision or the stated policy of the United Nations Environment Programme, nor does citing of trade names or commercial processes constitute endorsement. Acknowledgement This document was developed by a team led by Dr. Wan Asma Ibrahim Head of Bioen- ergy Programme, Forest Products Division, Forest Research Institute Malaysia (FRIM) under the overall guidance and supervision of Surya Prakash Chandak, Senior Pro- gramme Officer, International Environmental Technology Centre, Division of Technol- ogy, Industry & Economics, United Nations Environment Programme. -

Monarchy – a Royal History of London

Monarchy – A Royal History of London Module Code 4HIST007X Module Level 4 Length Session One, Three Weeks Site Central London Host Course London International Summer Programme Pre-Requisite None Assessment 40% Oral Presentation, 60% Written Coursework Special features This module may include additional costs for museum tickets. Site visits: as a part of the module, students will be visiting The British Museum, British Library, National Portrait Gallery, the Museum of London, Imperial War Museum. The students will also tour important royal sites in London. Note: these visits are subject to change. Summary of module content This course examines London as the historical setting for monarchy and national ceremonial. As such the course considers Royalty’s central place in British life and examines how its purpose and function have changed over the centuries. It also investigates Royalty’s influence on British history and society and its impact on government, culture and science. Finally the course will consider how the monarchy has adapted – and continues to adapt – to changing times and how critics react to it. Learning outcomes On successful completion of this module, a student will be able to: 1. Explain how key moments in history have affected the role of the monarchy 2. Identify and evaluate how the monarchy has changed and adapted over time in response to national and international issues 3. Identify the extent to which the monarchy’s influence on diplomacy, international relations, society, culture and science have shaped the United Kingdom and its place on the world stage 4. Relate places and objects in and around London to key moments in the history of the monarchy. -

On Palm Oil and Deforestation in Borneo

On Palm Oil and Deforestation in Borneo: A Step-Wise Model- Based Policy Analysis Yola Riana Effendi, Bramka Arga Jafino, Erik Pruyt Delft University of Technology - Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management Jaffalaan 5, 2626 BX, Delft, The Netherlands [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT Deforestation due to the increasing palm oil demand has been a major environmental issue in Indonesia, especially in Kalimantan on Borneo Island, where the growth of oil palm plantation is the highest. As the potential for oil palm plantations in Sumatra Island has been reached, expansion has moved to Kalimantan where forest coverage is still relatively high. Besides logging trees, land is cleared by burning the forest without proper procedures and neglecting the environmental surroundings of the forest. Consequently, the fire spreads and affects surrounding areas. This study attempts to explore the long-term dynamics of the forest coverage in Kalimantan and to design policies to reduce the damage caused by this expansion. Using a model-based adaptive robust design approach, we show that it is possible to reduce the percentage of simulation runs which forest coverage in 2100 is smaller than 15 million hectares from more than 80% to less than 15%. Ultimately, the percentage of simulation runs which forest coverage is less than 10 million hectares is even smaller than 2% after the final policies are executed. Keywords: palm oil, Borneo, deforestation, system dynamics, deep uncertainty, adaptive robust design I. BACKGROUND Palm oil constitutes the largest share of vegetable oil produced in the world because palm tree has the biggest yield of oil extraction compared to other crops.