Transcending Ego: Distinguishing Consciousness from Wisdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VT Module6 Lineage Text Major Schools of Tibetan Buddhism

THE MAJOR SCHOOLS OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM By Pema Khandro A BIRD’S EYE VIEW 1. NYINGMA LINEAGE a. Pema Khandro’s lineage. Literally means: ancient school or old school. Nyingmapas rely on the old tantras or the original interpretation of Tantra as it was given from Padmasambhava. b. Founded in 8th century by Padmasambhava, an Indian Yogi who synthesized the teachings of the Indian MahaSiddhas, the Buddhist Tantras, and Dzogchen. He gave this teaching (known as Vajrayana) in Tibet. c. Systemizes Buddhist philosophy and practice into 9 Yanas. The Inner Tantras (what Pema Khandro Rinpoche teaches primarily) are the last three. d. It is not a centralized hierarchy like the Sarma (new translation schools), which have a figure head similar to the Pope. Instead, the Nyingma tradition is de-centralized, with every Lama is the head of their own sangha. There are many different lineages within the Nyingma. e. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is the emphasis in the Tibetan Yogi tradition – the Ngakpa tradition. However, once the Sarma translations set the tone for monasticism in Tibet, the Nyingmas also developed a monastic and institutionalized segment of the tradition. But many Nyingmas are Ngakpas or non-monastic practitioners. f. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is that it is characterized by treasure revelations (gterma). These are visionary revelations of updated communications of the Vajrayana teachings. Ultimately treasure revelations are the same dharma principles but spoken in new ways, at new times and new places to new people. Because of these each treasure tradition is unique, this is the major reason behind the diversity within the Nyingma. -

An Excursus on the Subtle Body in Tantric Buddhism. Notes

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES EDITOR-IN-CHIEF A. K. Narain University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA EDITORS L. M.Joshi Ernst Steinkellner Punjabi University University of Vienna Patiala, India Wien, Austria Alexander W. Macdonald Jikido Takasaki Universite de Paris X University of Tokyo Nanterre, France Tokyo, fapan Bardwell Smith Robert Thurman Carleton College Amherst College Northfield, Minnesota, USA Amherst, Massachusetts, USA ASSISTANT EDITOR Roger Jackson FJRN->' Volume 6 1983 Number 2 CONTENTS I. ARTICLES A reconstruction of the Madhyamakdvatdra's Analysis of the Person, by Peter G. Fenner. 7 Cittaprakrti and Ayonisomanaskdra in the Ratnagolravi- bhdga: Precedent for the Hsin-Nien Distinction of The Awakening of Faith, by William Grosnick 35 An Excursus on the Subtle Body in Tantric Buddhism (Notes Contextualizing the Kalacakra)1, by Geshe Lhundup Sopa 48 Socio-Cultural Aspects of Theravada Buddhism in Ne pal, by Ramesh Chandra Tewari 67 The Yuktisas(ikakdrikd of Nagarjuna, by Fernando Tola and Carmen Dragonetti 94 The "Suicide" Problem in the Pali Canon, by Martin G. Wiltshire \ 24 II. BOOK REVIEWS 1. Buddhist and Western Philosophy, edited by Nathan Katz 141 2. A Meditators Diary, by Jane Hamilton-Merritt 144 3. The Roof Tile ofTempyo, by Yasushi Inoue 146 4. Les royaumes de I'Himalaya, histoire et civilisation: le La- dakh, le Bhoutan, le Sikkirn, le Nepal, under the direc tion of Alexander W. Macdonald 147 5. Wings of the White Crane: Poems of Tskangs dbyangs rgya mtsho (1683-1706), translated by G.W. Houston The Rain of Wisdom, translated by the Nalanda Transla tion Committee under the Direction of Chogyam Trungpa Songs of Spiritual Change, by the Seventh Dalai Lama, Gyalwa Kalzang Gyatso 149 III. -

The Nine Yanas

The Nine Yanas By Cortland Dahl In the Nyingma school, the spiritual journey is framed as a progression through nine spiritual approaches, which are typically referred to as "vehicles" or "yanas." The first three yanas include the Buddha’s more accessible teachings, those of the Sutrayana, or Sutra Vehicle. The latter six vehicles contain the teachings of Buddhist tantra and are referred to as the Vajrayana, or Vajra Vehicle. Students of the Nyingma teachings practice these various approaches as a unity. Lower vehicles are not dispensed with in favor of supposedly “higher” teachings, but rather integrated into a more refined and holistic approach to spiritual development. Thus, core teachings like renunciation and compassion are equally important in all nine vehicles, though they may be expressed in more subtle ways. In the Foundational Vehicle, for instance, renunciation involves leaving behind “worldly” activities and taking up the life of a celibate monk or nun, while in the Great Perfection, renunciation means to leave behind all dualistic perception and contrived spiritual effort. Each vehicle contains three distinct components: view, meditation, and conduct. The view refers to a set of philosophical tenets espoused by a particular approach. On a more experiential level, the view prescribes how practitioners of a given vehicle should “see” reality and its relative manifestations. Meditation consists of the practical techniques that allow practitioners to integrate Buddhist principles with their own lives, thus providing a bridge between theory and experience, while conduct spells out the ethical guidelines of each system. The following sections outline the features of each approach. Keep in mind, however, that each vehicle is a world unto itself, with its own unique philosophical views, meditations, and ethical systems. -

18 Phases Or Realms

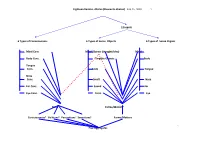

Eighteen Realms- dhatus (Elements-dhatus) Feb.16, 2020 1. 12 inputs 6 Types of Consciousness 6 Types of Sense Objects 6 Types of Sense Organs Mind Cons. Mind Objects (thought/idea) Mind Body Cons. Tangible Objects Body Tongue Cons. Taste Tongue Nose Cons. Smell Nose Ear Cons. Sound Ear Eye Cons. Form Eye Mind Forms/Matters1 Consciousness5 Volitions4 Perceptions3 Sensations2 Forms/Matters . Five Aggregates P2. 1. Rupa: Form or (Matter) Aggregate: the Four Great Elements: 1) Solidity, 2) Fluidity, 3) Heat, 4) Wind/Motion which include the five physical sense-organs i.e. the faculties of the eye, ear, nose, tongue, body besides the brain/mind (note: the brain is an organ, not the mind which is an abstract noun). These sense organs are in contact with the external objects of visible form, sound, odor, taste and tangible things and the mind faculty which corresponds to the intangible objects such as thoughts, ideas, and conceptions. 2. Vedana: Sensations- Feelings (generated by the 6 sense organs eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, brain/mind) 3. Samjna: Perception (Conception): The mental function of shape, color, length, pain, pleasure, un-pleasure, neutral. 4. Samskara: Volition-Mental formation: i.e. flashback, will, intention, or the mental function that accounts for craving. 5. Vijnana : Consciousness( Cognition, discrimination-Mano consciousness): the respective consciousness arises when 6 sense organs eye , ear, nose, tongue, body, brain/mind are in contact with the 6 sense objects form , sound, smell, taste, tangible objects , and mental objects. Please be note that Vijnana Consciousness can be further classified into the 6th, 7th and the 8th according to the Vijhanavada (Mere-Mind) School: Mano Consciousness (6th Consciousness): The front 5 senses report to and co-ordinate by the 6th senses in reaction to the 6 sense objects, gather sense data, discriminate, recall it’s the active, coarse and manifest portion of the Manas Vijnanna. -

Lankavatara-Sutra.Pdf

Table of Contents Other works by Red Pine Title Page Preface CHAPTER ONE: - KING RAVANA’S REQUEST CHAPTER TWO: - MAHAMATI’S QUESTIONS I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI XXII XXIII XXIV XXV XXVI XXVII XXVIII XXIX XXX XXXI XXXII XXXIII XXXIV XXXV XXXVI XXXVII XXXVIII XXXIX XL XLI XLII XLIII XLIV XLV XLVI XLVII XLVIII XLIX L LI LII LIII LIV LV LVI CHAPTER THREE: - MORE QUESTIONS LVII LVII LIX LX LXI LXII LXII LXIV LXV LXVI LXVII LXVIII LXIX LXX LXXI LXXII LXXIII LXXIVIV LXXV LXXVI LXXVII LXXVIII LXXIX CHAPTER FOUR: - FINAL QUESTIONS LXXX LXXXI LXXXII LXXXIII LXXXIV LXXXV LXXXVI LXXXVII LXXXVIII LXXXIX XC LANKAVATARA MANTRA GLOSSARY BIBLIOGRAPHY Copyright Page Other works by Red Pine The Diamond Sutra The Heart Sutra The Platform Sutra In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu Lao-tzu’s Taoteching The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain The Zen Works of Stonehouse: Poems and Talks of a 14th-Century Hermit The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma P’u Ming’s Oxherding Pictures & Verses TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE Zen traces its genesis to one day around 400 B.C. when the Buddha held up a flower and a monk named Kashyapa smiled. From that day on, this simplest yet most profound of teachings was handed down from one generation to the next. At least this is the story that was first recorded a thousand years later, but in China, not in India. Apparently Zen was too simple to be noticed in the land of its origin, where it remained an invisible teaching. -

The Kayas / Bodies of a Buddha

The Kayas / Bodies of a Buddha The original meaning of the Sanskrit word Kaya (Tibetan: sku/ku) is 'that which is accumulated'. In English Kaya is translated as 'body'. However, the Kayas of Buddhas do not literally refer only to the form aggregates of Buddhas but also to Buddhas themselves, to their various attributes, and so forth. There are different ways to categorize Kayas: 1. The category into five Kayas 2. The category into four Kayas 3. The category into three Kayas 4. The category into two Kayas 1. The category into five Kayas The category into five Kayas refers to: I. The Dharmakaya / Truth Body (chos sku / choe ku) II. The Svabhavakaya / Nature Body (ngo bo nyid sku / ngo wo nyi ku) III. The Jnanakaya / Wisdom Truth Body (ye shes chos sku / ye she choe ku) IV. The Sambhogakaya / Enjoyment Body (longs sku / long ku) V. The Nimanakaya / Emanation Body (sprul sku / truel ku) Here the basis of the category is Kaya, which means that Kaya is categorized or classified into the five Kayas. I. The Dharmakaya / Truth Body Kaya and Dharmakaya are synonymous. Whatever is a Kaya is necessarily a Dharmakaya and vice versa. The definition of a Dharmakaya is: a final Kaya that is attained in dependence on meditating on its attaining agents, the three exalted knowers. The three exalted knowers are: a) Knower of basis (the Arya paths in the continua of Hearers and Solitary Realizers) b) Knower of paths (the Arya paths in the continua of Buddhas and of Bodhisattvas who have reached the Mahayana path of seeing or the Mahayana path of meditation) c) Exalted knower of aspects (the Arya paths, that is, omniscient mental consciousnesses, in the continua of Buddhas) II. -

Hinduism and Social Work

5 Hinduism and Social Work *Manju Kumar Introduction Hinduism, one of the oldest living religions, with a history stretching from around the second millennium B.C. to the present, is India’s indigenous religious and cultural system. It encompasses a broad spectrum of philosophies ranging from pluralistic theism to absolute monism. Hinduism is not a homogeneous, organized system. It has no founder and no single code of beliefs; it has no central headquarters; it never had any religious organisation that wielded temporal power over its followers. Hinduism does not have a single scripture as the source of its various teachings. It is diverse; no single doctrine (or set of beliefs) can represent its numerous traditions. Nonetheless, the various schools share several basic concepts, which help us to understand how most Hindus see and respond to the world. Ekam Satya Viprah Bahuda Vadanti — “Truth is one; people call it by many names” (Rigveda I 164.46). From fetishism, through polytheism and pantheism to the highest and the noblest concept of Deity and Man in Hinduism the whole gamut of human thought and belief is to be found. Hindu religious life might take the form of devotion to God or gods, the duties of family life, or concentrated meditation. Given all this diversity, it is important to take care when generalizing about “Hinduism” or “Hindu beliefs.” For every class of * Ms. Manju Kumar, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar College, Delhi University, Delhi. 140 Origin and Development of Social Work in India worshiper and thinker Hinduism makes a provision; herein lies also its great power of assimilation and absorption of schools of philosophy and communities of people, (Theosophy, 1931). -

Svarupa of Thejiva Our Original Spiritual Identity Karisma-Section Is a Trademark of Gaudiya Vedanta Publications

Svarupa of theJiva Our Original Spiritual Identity karisma-section is a trademark of gaudiya vedanta publications. © (YEAR) gaudiya vedantaexcept where publications. otherwise noted, some only rights the text reserved. (not the design, photos, art, etc.) in this book is licensed under the creative commons attribution-no derivative works 3.0 unported license. to view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/3.0/ permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at www.purebhakti.com/pluslicense or write to: [email protected] all translations, purports, and excerpts of lectures by Śrīla bhaktivedānta svāmī prabhupāda are courtesy of BBT international. they are either clearly mentioned as his, or marked with an asterisk (*). verse translations marked with three asterisks (***) are by the disciples of Śrīla bhaktivedāntaŚrī s vāmīBhakti-rasāmṛta-sindhu prabhupāda. © bhaktivedantaSārārtha-darśinī book ṭīkātrust intl.Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam Govinda-bhāṣya verse translations of , of 1.6.28, and (2.3.26, 28) are by Śrīpāda bhānu svāmī.Govinda-bhāṣya sutras Paramātma sandarbha verse translations of ( 4.4.1,2guru-paramparā ) and - (29.1; 105.80) are by kuśakrata dāsa photo of Śrīla nārāyaṇa gosvāmī mahārāja in the guru-paramparā– kṛṣṇa-mayī dāsī. used with permission. photo on p. 1, 11 – subala-sakhā dāsa (s. florida). used with permission. photo of Śrīla bhaktivedānta svāmī mahārāja in the and on p. 23, 127, 143 – scans provided by bhaktivedanta archives. used with permission. photo on p. 79 – Jānakī dāsī. used with permission. photo on p. 152 – vasanti dāsī. used with permission. photo on p. 40 – bigstock. used with permission. -

Eight Manifestations of Padmasambhava Essay

Mirrors of the Heart-Mind - Eight Manifestations of Padmasam... http://huntingtonarchive.osu.edu/Exhibitions/sama/Essays/AM9... Back to Exhibition Index Eight Manifestations of Padmasambhava (Image) Thangka, painting Cotton support with opaque mineral pigments in waterbased (collagen) binder exterior 27.5 x 49.75 inches interior 23.5 x 34.25 inches Ca. 19th century Folk tradition Museum #: 93.011 By Ariana P. Maki 2 June, 1998 Padmasambhava, also known as Guru Rinpoche, Padmakara, or Tsokey Dorje, was the guru predicted by the Buddha Shakyamuni to bring the Buddhist Dharma to Tibet. In the land of Uddiyana, King Indrabhuti had undergone many trials, including the loss of his young son and a widespread famine in his kingdom. The Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara felt compassion for the king, and entreated the Buddha Amitabha, pictured directly above Padmasambhava, to help him. From his tongue, Amitabha emanated a light ray into the lake of Kosha, and a lotus grew, upon which sat an eight year old boy. The boy was taken into the kingdom of Uddiyana as the son of King Indrabhuti and named Padmasambhava, or Lotus Born One. Padmasambhava grew up to make realizations about the unsatisfactory nature of existence, which led to his renunciation of both kingdom and family in order to teach the Dharma to those entangled in samsara. Over the years, as he taught, other names were bestowed upon him in specific circumstances to represent his realization of a particular aspect of Buddhism. This thangka depicts Padmasambhava, in a form also called Tsokey Dorje, as a great guru and Buddha in the land of Tibet. -

Distinguishing Dharma and Dharmata by Asanga and Maitreya with a Commentary by Thrangu Rinpoche Geshe Lharampa

Distinguishing Dharma and Dharmata by Asanga and Maitreya with a Commentary by Thrangu Rinpoche Geshe Lharampa Translated by Jules Levinsion Asanga in the fourth century meditated on Maitreya for twelve years and then was able to meet the Maitreya Buddha (the next Buddha) directly, who gave him five works including this text. Asanga then went on to found the Mind-only or Chittamatra school of Buddhism. This text, which contains both the root verses of Maitreya and a commentary on these verses by Thrangu Rinpoche, begins by giving the characteristics of dharma which is ordinary phenomena as we perceive it as unenlightened beings. Phenomena is described in detail by giving its characteristics, its constituents or elements, and finally its source which is the mind. Discussed are the eight consciousnesses especially the alaya consciousness and how it creates the appearance of this world. Understanding dharma allows us to understand how we build up a false illusion of this world and this then leads to our problems in samsara. Next, the text discusses dharmata or phenomena as it really is, not as it appears, in detail. In describing this sphere of reality or pure being, the text gives the characteristics of dharmata, where it is located, and the kinds of meditation needed to develop a perception of the true nature of reality. Finally, there is a discussion of how one transforms ordinary dharma into dharmata, i.e. how one reaches awakening or enlightenment. This is discussed in ten famous points and this is actually a guide or a map to how to proceed along the Buddhist path. -

The Tulku System in Tibetan Buddhism: Its Reliability, Orthodoxy and Social Impacts

The Tulku System in Tibetan Buddhism: Its Reliability, Orthodoxy and Social Impacts By Ramin Etesami A thesis submitted to the graduate school in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the International Buddhist College, Thailand March, 20 Abstract The Tulku institution is a unique characteristic of Tibetan Buddhism with a central role in this tradition, to the extent that it is present in almost every aspect of Tibet’s culture and tradition. However, despite this central role and the scope and diversity of the socio-religious aspects of the institution, only a few studies have so far been conducted to shed light on it. On the other hand, an aura of sacredness; distorted pictures projected by the media and film industries;political propaganda and misinformation; and tendencies to follow a pattern of cult behavior; have made the Tulku institution a highly controversial topic for research; and consequently, an objective study of the institution based on a critical approach is difficult. The current research is an attempt to comprehensively examine different dimensions of the Tulku tradition with an emphasis on the issue of its orthodoxy with respect to the core doctrines of Buddhism and the social implications of the practice. In this research, extreme caution has been practiced to firstly, avoid any kind of bias rooted in faith and belief; and secondly, to follow a scientific methodology in reviewing evidence and scriptures related to the research topic. Through a comprehensive study of historical accounts, core Buddhist texts and hagiographic literature, this study has found that while the basic Buddhist doctrines allow the possibility for a Buddhist teacher or an advanced practitioner to “return back to accomplish his tasks, the lack of any historical precedence which can be viewed as a typical example of the practice in early Buddhism makes the issue of its orthodoxy equivocal and relative. -

A Guide to Shamatha Meditation

A Guide to Shamatha Meditation by Thrangu Rinpoche Geshe Lharampa Copyright © 1999 by Namo Buddha Publications. This teaching is taken from the much longer The Four Foundations of Buddhist Practice by Thrangu Rinpoche. The teachings are based on Pema Karpo’s Mahamudra Meditation Instructions. This teaching was given in Samye Ling in Scotland in 1980. These inexpensive booklets may be purchased in bulk from Namo Buddha Publications. If it is translated into any other language, we would appreciate it if a copy of the translation. The technical terms have been italicized the first time to alert the reader that they may be found in the Glossary. Dorje Chang Lineage Prayer Great Vajradhara, Tilopa, Naropa Marpa, Milarepa, and lord of the dharma Gampopa The knower of the three times, the omniscient Karmapa The holders of the lineage of the four great and eight lesser schools. The lamas Trikung, Tsalung, Tsalpa, and glorious Drungpa and others To all those who have thoroughly mastered the profound path of mahamudra The Dagpo Kagyu who are unrivalled as protectors of beings I pray to you, the Kagyu gurus, to grant your blessing So that I may follow your tradition and example. The teaching is that detachment is the foot of meditation; Not being possessed by food or wealth. To the meditator who gives up the ties to this life, Grant your blessing so that he ceases to be attached to honor or ownership. The teaching is that devotion is the head of meditation. The lama opens the gate to the treasury of the profound oral teachings, To the meditator who always turns to him, Grant your blessing so that genuine devotion is born in him.