Matthew Carey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Arts & Humanities

Journal of Arts & Humanities Constructing an ‘Outlandish’ Narrative of Self: The Role of Music in Muslim Experience Reem M Hilal1 ABSTRACT This paper explores the way in which Muslims, particularly those in the Diaspora, use music as an alternative medium to negotiate a narrative of self that reflects their performance of their faith and the issues that concern them. The focus will be on the music of the Danish based music group Outlandish. Specifically, music has become an important space to dismantle and reformulate discussions on identity and offers insight into the way language, religion, and resistance are deployed in a medium with increasing currency. Outlandish has garnered an international audience; through mediums such as YouTube, their music resonates with Muslims and other minority groups in the diaspora faced with similar issues of identification. This paper addresses the questions: how is music employed to construct narratives of self that challenge boundaries? How does music engage the issue of representation for those who face exclusion? How can their work be read in the contemporary setting where globalization has brought different cultural worldviews into contact, at times producing dialogue and constructive exchange and at other times leading to discernible violence, engendering a more pronounced sense of alienation and exclusion? Through their music, Outlandish expresses the ways in which what differentiates between people binds them through a process of recognition, to borrow from Judith Butler. Focusing on Outlandish’s music, I examine the role of music in the negotiation and construction of narratives of self by contemporary Muslims that counter those that have been constructed for and against them. -

Bookere/Managements Kontakt Kontaktmail Adresse Postnummer/By Hjemmeside Telefon Note

Bookere/managements Kontakt Kontaktmail Adresse Postnummer/by Hjemmeside Telefon Note Volbeat, L.O.C., Soleima, Thøger 3rd Tsunami Jesper Frydenlund [email protected] Ewaldsgade 9, 1 + 2 2200 København N www.3rd-tsunami.com 35348348 Dixgaard, Lord Siva m.fl. Mek Pek, Anna Spejlæg, Jan Alive Music APS Mek Falk/Adm. Direktør [email protected] Borggade 1, 2. TH. 8000 Aarhus C http://www.alivemusic.dk 70202208 Svarrer m.fl. Peter Sørensen, [email protected] Thomas Helmig, D.A.D., Tina Beatbox Booking Ravnsborggade 2, 1. sal 2200 København N http://beatboxbooking.dk 28810094 Dickow, Trentemøller, Choir Of Hans Emil Hansen [email protected] Young Believers m.fl. Koncertarrangør - primært Mads Sørensen & Xenia Nørrebrogade 52C, 3. http://www. Beatbox Entertainment info@beatboxentertainment 2200 København N koncerter & shows med Grigat TV beatboxentertainment.dk .dk internationale bands i DK Morten Elley [email protected] 70127722 Martin Rintza [email protected] 42365685 MØ, Chinah, Av Av Av, Rasmus http://www.birdseyeagency. Birdseye Sarah Sølvsteen [email protected] Kronprinsensgade 1 1114 København K 70127722 Walter, Phlake, Sekouia, dk Kellermensch, De Eneste To m.fl. Theis Smedegaard [email protected] 70127722 Nicolai Demuth [email protected] 28770677 Oh Land, Savage Rose, Nelson Bullet Booking Jesper Kemp [email protected] Kongelundsvej 88F 2300 København S http://bulletbooking.dk/ 20601145 Can, D/Troit m.fl. Carpark North, Alex Vargas, Anya, Copenhagen Music Rasmus Søby [email protected] Prags Boulevard 47 2300 København S http://cphmusic.dk 40741877 Lukas Graham, Saveus m.fl. Copenhagen Music Jimmi Riise [email protected] Ryesgade 12, 2 8000 Aarhus C Event booking & production rasmus@damsholt. -

My Voice Is My Weapon: Music, Nationalism, and the Poetics Of

MY VOICE IS MY WEAPON MY VOICE IS MY WEAPON Music, Nationalism, and the Poetics of Palestinian Resistance David A. McDonald Duke University Press ✹ Durham and London ✹ 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Cover by Heather Hensley. Interior by Courtney Leigh Baker Typeset in Minion Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data McDonald, David A., 1976– My voice is my weapon : music, nationalism, and the poetics of Palestinian resistance / David A. McDonald. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-5468-0 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-5479-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Palestinian Arabs—Music—History and criticism. 2. Music—Political aspects—Israel. 3. Music—Political aspects—Gaza Strip. 4. Music—Political aspects—West Bank. i. Title. ml3754.5.m33 2013 780.89′9274—dc23 2013012813 For Seamus Patrick McDonald Illustrations viii Note on Transliterations xi Note on Accessing Performance Videos xiii Acknowledgments xvii introduction ✹ 1 chapter 1. Nationalism, Belonging, and the Performativity of Resistance ✹ 17 chapter 2. Poets, Singers, and Songs ✹ 34 Voices in the Resistance Movement (1917–1967) chapter 3. Al- Naksa and the Emergence of Political Song (1967–1987) ✹ 78 chapter 4. The First Intifada and the Generation of Stones (1987–2000) ✹ 116 chapter 5. Revivals and New Arrivals ✹ 144 The al- Aqsa Intifada (2000–2010) CONTENTS chapter 6. “My Songs Can Reach the Whole Nation” ✹ 163 Baladna and Protest Song in Jordan chapter 7. Imprisonment and Exile ✹ 199 Negotiating Power and Resistance in Palestinian Protest Song chapter 8. -

What If Pakistan Fails? India Isn’T Worried

C. Raja Mohan What If Pakistan Fails? India Isn’t Worried ... Yet The issue of failed states has risen to the forefront of international relations in the last few years, with Pakistan widely considered as a potential case. The Indian establishment has closely followed U.S. debate over the prospect of Pakistan weakening and disintegrating. Although many Indians relish this thought, as it would weaken its historical adversary, few decisionmakers in New Delhi are convinced that the likelihood of this pros- pect lies just around the corner. India is currently in no rush to prepare for such a contingency. Some in New Delhi suspect that attempts to diagnose Pakistan with failed-state syndrome merely serve to perpetuate the long-standing alliance between Washington and Islamabad. Pakistani rulers have been adept at manipulating Washington’s fears of political uncertainty in their nation. At every stage, Washington tends to argue that the current regime in Islamabad is indeed indispensable and often advises New Delhi to ease up on immedi- ate disputes with its western neighbor. New Delhi recognizes Washington’s enduring political dependence on Islamabad, especially on Pakistan’s mili- tary, in order to pursue its political interests in south and southwest Asia. Washington’s decision, for whatever reason, to discretely handle the Abdul Qadeer Khan affair—the so-called father of the Pakistani bomb whose ex- tensive network of nuclear proliferation was unveiled earlier this year—con- firms New Delhi’s assessment that Washington will allow Islamabad to get away with anything. Washington declared Khan an individual offender and allowed the Pakistani government to pardon Khan rather than consider him part of a system in Pakistan that has deliberately promoted the spread of weapons of mass destruction. -

The Lost Towns of Honduras

William V. Davidson The Lost Towns of Honduras. Eight once-important places that dropped off the maps, with a concluding critical recapitulation of documents about the fictitious Ciudad Blanca of La Mosquitia. Printed for the author Memphis, Tennessee, USA 2017 i The Lost Towns of Honduras. ii In Recognition of the 100th Anniversary of the Honduran Myth of Ciudad Blanca – The last of the “great lost cities” that never was. Design by Andrew Bowen Davidson North Carolina State University Raleigh, North Carolina, USA Cover Photograph: Church ruin, Celilac Viejo By author 1994 All rights reserved Copyright © 2017 William V. Davidson Memphis, Tennessee, USA iii Table of Contents Table of Contents iv Preface v I. Introduction 1 II. Nueva Salamanca (1544-1559) 4 III. Elgueta (1564-1566) 20 IV. Teculucelo (1530s - 1590) 26 V. Cárcamo/Maitúm (1536-1632) 31 VI. Munguiche (1582-1662) 39 VII. Quesaltepeque (1536-1767) 45 VIII. Cayngala (1549-1814) 51 IX. Cururú (1536-1845) 56 X. Concluding Remarks 65 XI. Ciudad Blanca (1917-Never Was) 67 XII. Concluding Remarks 125 Bibliography 127 iv Preface Over the last half century my intention has been to insert a geographical perspective into the historical study of indigenous Honduras. Historical research, appropriately, focuses on "the what,” “the who," and "the when.” To many historians, "the where," the geographical component, is much less important, and, indeed, is sometimes overlooked. One of my students once reflected on the interplay of the two disciplines: “Historical geography, in contrast to history, focuses on locations before dates, places before personalities, distributions before events, and regions before eras. -

Musikselskaber 2012 – Tal Og Perspektiver?

MUSIK- SELSKABER 2012 tal og perspektiver Musikselskaber 2012 - tal og perspektiver s. 2 FOTO: sophie bech FORORD Det danske musikmarked er i rivende ud- Det betyder ikke, at alle udfordringer er for- vikling. Det viser tallene for 2012 tydeligere svundet som dug for solen, og at vi nu skal end et stjerneskud på en mørk nattehim- læne os selvtilfredse tilbage i stolen. Vi har mel. For første gang nogensinde er den digi- stadig en vigtig opgave med at skabe trans- tale omsætning for salg af indspillet musik parens, så de massive mængder data, digi- større end den fysiske. Og selvom vi også i taliseringen fører med sig, giver mening for 2012 oplevede et mindre fald i den samlede verden omkring os. Og så skal vi fortsætte omsætning, er det med blot 3 % tale om den med den progressive forbrugerorienterede mindste nedgang siden årtusindeskiftet. tilgang til det digitale marked, der er på vej til at bringe os ud af tusmørket og ind i en Hvad der imidlertid er endnu mere inte- ny spændende virkelighed. ressant, er de digitale vækstkurver, vi har set i det forgangne år. Indtægterne fra Vi er der ikke helt endnu, men målet er streamingtjenester som Spotify, WiMP og klart. Vi vil være med til at forme en bære- Play er næsten fordoblet i 2012, og de udgør dygtig fremtid hvor det, at vi forbruger og allerede nu en fjerdedel af musikselskaber- deler musik med hinanden, er positivt for nes samlede omsætning. Og vi er først lige både danske musikelskere, danske musik- begyndt. Samtidig fortsætter danskerne selskaber og danske musikere. -

President Jean-Claude Juncker Wednesday, 29 June 2016 European Commission Rue De La Loi 200 1049 Brussels Belgium

President Jean-Claude Juncker Wednesday, 29 June 2016 European Commission Rue de la Loi 200 1049 Brussels Belgium Re. Securing a sustainable future for the European music sector Dear President Juncker, As recording artists and songwriters from across Europe and artists who regularly perform in Europe, we believe passionately in the value of music. Music is fundamental to Europe’s culture. It enriches people’s lives and contributes significantly to our economies. This is a pivotal moment for music. Consumption is exploding. Fans are listening to more music than ever before. Consumers have unprecedented opportunities to access the music they love, whenever and wherever they want to do so. But the future is jeopardised by a substantial “value gap” caused by user upload services such as Google’s YouTube that are unfairly siphoning value away from the music community and its artists and songwriters. This situation is not just harming today’s recording artists and songwriters. It threatens the survival of the next generation of creators too, and the viability and the diversity of their work. The value gap undermines the rights and revenues of those who create, invest in and own music, and distorts the market place. This is because, while music consumption is at record highs, user upload services are misusing “safe harbour” exemptions. These protections were put in place two decades ago to help develop nascent digital start-ups, but today are being misapplied to corporations that distribute and monetise our works. Right now there is a unique opportunity for Europe’s leaders to address the value gap. -

Pakistan--Violence Versus Stability

Pakistan—Voilence versus Stability versus Pakistan—Voilence Pakistan—Violence versus Stability versus Pakistan—Violence a report of the csis burke chair in strategy Pakistan—Violence versus Stability a national net assessment 1800 K Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 C E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org ordesman Authors Anthony H. Cordesman Varun Vira Cordesman / V ira / Vira September 2011 ISBN 978-0-89206-652-0 CSIS Ë|xHSKITCy066520zv*:+:!:+:! CSIS a report of the csis burke chair in strategy Pakistan—Violence versus Stability a national net assessment Authors Anthony H. Cordesman Varun Vira September 2011 About CSIS At a time of new global opportunities and challenges, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) provides strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to decisionmakers in government, international institutions, the private sector, and civil society. A bipartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., CSIS conducts research and analysis and devel- ops policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Founded by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke at the height of the Cold War, CSIS was dedicated to finding ways for America to sustain its prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. Since 1962, CSIS has grown to become one of the world’s preeminent international policy institutions, with more than 220 full-time staff and a large network of affiliated scholars focused on defense and security, regional stability, and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global development and economic integration. Former U.S. -

Festsortimentet Playliste May 2012.Xlsx

Kunster Album Album årti 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 2000 Abba Abba Gold Greatest Hits 1990 Ac/Dc Black Ice 2000 Ace Of Base The Golden Ratio 2010 Adele 21 2010 Aerosmith Rocks 1970 Aerosmith The Very Best Of Aerosmith - Tour Edition 2000 A-Ha Headlines And Deadlines - The Hits Of A-Ha 1990 Alphabeat Alphabeat 2000 Alphabeat The Beat Is... 2010 Anastacia Anastacia Freak Of Nature 2000 Ankerstjerne Ankerstjerne 2010 Appleton Everything`s Eventual 2000 Aqua Megalomania 2010 Atomic Kitten Right Now (Cd1) 2000 Atomic Kitten Right Now (Cd2) - Aura Columbine 2000 Backstreet Boys Everybody - Backstreet Boys Shape Of Me Heart 2000 Bamse Love Me Tender 2000 Beth Hart 37 Days 2000 Beth Hart My California 2010 Big Fat Snake Beautiful Thing 1990 Big Fat Snake Between The Devil And The Big Blue Sea 2000 Big Fat Snake Big Fat Snake 1990 Big Fat Snake Born Lucky 1990 Big Fat Snake Fight For Your Love 1990 Big Fat Snake Flames 1990 Big Fat Snake Live - Big Fat Snake Midnight Mission 1990 Big Fat Snake More Fire 2000 Big Fat Snake Play It By Ear 2000 Big Fat Snake Running Man 2000 Big Fat Snake Www.Bigfatsnake.Com 1990 Bikstok Røgsystem Over Stok Og Sten 2000 Billy Idol Idol Songs - 11 Of The Best 1980 Birthe Kjær Dejlige Danske... Birthe Kjaer - CD 1 - Birthe Kjær Dejlige Danske... Birthe Kjaer - CD 2 - Birthe Kjær Gennem Tiden CD 1 1990 Birthe Kjær Gennem Tiden CD 2 1990 Bob Marley Legend [Bonus Tracks] 1980 Bon Jovi Crossroad - Bruce Springsteen Greatest Hits' 1990 Bruce Springsteen Wrecking Ball [Deluxe Edition] 2012 Bruno Mars Doo-Wops & Hooligans 2010 Bryan Adams The Best Of Me 1990 Burhan G Burhan G 2010 Caroline Henderson No. -

Seneste Update: Dec-‐13 Mastercatid Artist Title 10Er Britney Spears 3

Seneste update: Dec-13 MasterCatID Artist Title 10er Britney Spears 3 10er MariaMatilde Band 1000 Lysår (Gettic Remix) 10er Lady GaGa Bad Romance 10er Robbie Williams Bodies 10er Norah Jones CHasing Pirates 10er NabiHa Deep Sleep (Radio edit) 10er Jay Sean Down 10er Rasmus SeebacH Glad igen 10er Leona Lewis Happy 10er Amanda Jenssen Happyland 10er Joey Moe Jorden Er Giftig 10er THe Raveonettes Last Dance 10er Taylor Swift Love Story 10er Timbaland Morning After Dark (feat. Nelly Furtado & 10er Paloma Faith New York (Radio Edit) 10er Selvmord Råbe Under Vand 10er Daniel Merriweather Red 10er Bring Det På Ring Til Politiet 10er RiHanna Russian Roulette 10er SHakira She Wolf 10er Alexander Brown & Morten Hampenberg Skub Til Taget (Radio Edit) [feat. YepHa] 10er AlpHabeat The Spell 10er Ke$ha TiK ToK 10er Muse Uprising 10er Jason Derulo WHatcHa Say 10er JoHn Mayer WHo Says 10er Kasper Bjørke Young Again (Radio Edit) 10er Norah Jones Even ThougH 10er Susan Boyle I Dreamed a Dream 10er Magtens Korridorer Milan Allé 10er Mariah Carey Obsessed 10er Miley Cyrus Party In the U.s.a. 10er Black Eyed Peas Meet Me Halfway 10er Miley Cyrus WHen I Look At You 10er Rasmus SeebacH Lidt I Fem 10er Medina Ensom 10er MicHael Bublé Haven't Met You Yet 10er Emma OS 2 (Svenstrup & Vendelboe Radio Mix) 10er Taylor Swift You Belong With Me 10er Owl City Fireflies 10er Jokeren Den Eneste Anden 10er Jack WHite & Alicia Keys Another Way To Die 10er Jay-Z feat. Alicia Keys Empire State Of Mind 10er MicHael Jackson THis Is It 10er CHanée & N'Evergreen In a Moment like THis (Dansk Melodi Grand Prix 10er Adam Lambert WHataya Want from Me 10er BurHan G Jeg Vil Ha' Dig For Mig Selv 10er BurHan G Mest Ondt (feat. -

Programming; Providing an Environment for the Growth and Education of Theatre Professionals, Audiences, and the Community at Large

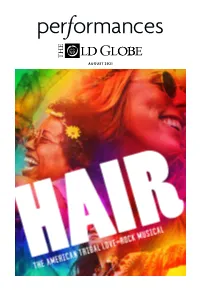

AUGUST 2021 WELCOME BACK Welcome to The Old Globe and this production of Hair. We thank you for being a crucial part of what we do, and supporting us through our extended intermission. Now more than ever, as we return to live performances, our goal is to serve all of San Diego and beyond through the art of theatre. Below are the mission and values that drive our work. MISSION STATEMENT The mission of The Old Globe is to preserve, strengthen, and advance American theatre by: creating theatri- cal experiences of the highest professional standards; producing and presenting works of exceptional merit, designed to reach current and future audiences; ensuring diversity and balance in programming; providing an environment for the growth and education of theatre professionals, audiences, and the community at large. STATEMENT OF VALUES The Old Globe believes that theatre matters. Our commitment is to make it matter to more people. The values that shape this commitment are: TRANSFORMATION Theatre cultivates imagination and empathy, enriching our humanity and connecting us to each other by bringing us entertaining experiences, new ideas, and a wide range of stories told from many perspectives. INCLUSION The communities of San Diego, in their diversity and their commonality, are welcome and reflected at the Globe. Access for all to our stages and programs expands when we engage audiences in many ways and in many places. EXCELLENCE Our dedication to creating exceptional work demands a high standard of achievement in everything we do, on and off the stage. STABILITY Our priority every day is to steward a vital, nurturing, and financially secure institution that will thrive for generations. -

The Construction of Blackness in Honduran Cultural Production

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Spanish and Portuguese ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 9-10-2010 The onsC truction of Blackness in Honduran Cultural Production A. Erin Mason-Montero Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/span_etds Recommended Citation Mason-Montero, A. Erin. "The onC struction of Blackness in Honduran Cultural Production." (2010). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/span_etds/1 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Spanish and Portuguese ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CONSTRUCTION OF BLACKNESS IN HONDURAN CULTURAL PRODUCTION BY ERIN AMASON MONTERO B.A., Spanish and Psychology, California Lutheran University, 1996 M.A., Latin American Studies, University of New Mexico, 2001 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Spanish and Portuguese The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July, 2010 THE CONSTRUCTION OF BLACKNESS IN HONDURAN CULTURAL PRODUCTION BY ERIN AMASON MONTERO ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Spanish and Portuguese The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July, 2010 © 2010, Erin Colleen Amason Montero iv DEDICATION I dedicate my work to the past and present generations of my family: Diane and Katiya. My mother Diane Clare (1942-2005) taught me to value knowledge, but unfortunately she could not see me graduate. My daughter Katiya Clare was born in 2007, the year in which I started to write my dissertation, and the hope for a happy future with my precious daughter was what served as my inspiration to finish.