MORENA-THESIS-2013.Pdf (7.293Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Fashion

^ jmnJinnjiTLrifiriniin/uuinjirirLnnnjmA^^ iJTJinjinnjiruxnjiJTJTJifij^^ LIBRARY THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA BARBARA FROM THE LIBRARY OF F. VON BOSCHAN X-K^IC^I Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from Microsoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/evolutionoffashiOOgardiala I Hhe Sbolution of ifashion BY FLORENCE MARY GARDINER Author of ^'Furnishings and Fittings for Every Home" ^^ About Gipsies," SIR ROBERT BRUCE COTTON. THE COTTON PRESS, Granvii^le House, Arundel Street, VV-C- TO FRANCES EVELYN, Countess of Warwick, whose enthusiastic and kindly interest in all movements calculated to benefit women is unsurpassed, This Volume, by special permission, is respectfully dedicated, BY THE AUTHOR. in the year of Her Majesty Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee, 1897. I I I PREFACE. T N compiling this volume on Costume (portions of which originally appeared in the Lndgate Ilhistrated Magazine, under the editorship of Mr. A. J. Bowden), I desire to acknowledge the valuable assistance I have received from sources not usually available to the public ; also my indebtedness to the following authors, from whose works I have quoted : —Mr. Beck, Mr. R. Davey, Mr. E. Rimmel, Mr. Knight, and the late Mr. J. R. Planchd. I also take this opportunity of thanking Messrs, Liberty and Co., Messrs. Jay, Messrs. E. R, Garrould, Messrs. Walery, Mr. Box, and others, who have offered me special facilities for consulting drawings, engravings, &c., in their possession, many of which they have courteously allowed me to reproduce, by the aid of Miss Juh'et Hensman, and other artists. The book lays no claim to being a technical treatise on a subject which is practically inexhaustible, but has been written with the intention of bringing before the general public in a popular manner circumstances which have influenced in a marked degree the wearing apparel of the British Nation. -

Linguistic and Extralinguistic Challenges in Translation of English Footwear Terminology Into Romanian

Journal of Social Sciences Vol. 1, no. 2 (2018), pp. 47 - 55 Fascicle Social Science ISSN 2587-3490 Topic Philology ang linguistics eISSN 2587-3504 LINGUISTIC AND EXTRALINGUISTIC CHALLENGES IN TRANSLATION OF ENGLISH FOOTWEAR TERMINOLOGY INTO ROMANIAN Inga Stoianova Free International University of Moldova, 52 Vlaicu Pârcalab Str, Chișinău, Republic of Moldova [email protected] Received: October, 20, 2018 Accepted: November, 22, 2018 Abstract. The footwear terminology represents a great interest and challenge in translation, as world-famous brands, daily competing with each other, create almost monthly new models of footwear, thus, introducing new terminological designations for shoes and requiring their adequate translation using certain translation techniques. A large layer of English footwear specialized vocabulary is rendered into Romanian by calque, description and transcription in the absence of the proper equivalent in the target language. Subsequently, language replenishment with borrowed lexical units takes place, having a positive effect on the language vocabulary volume. However, the abundance of foreign words creates misunderstandings in the specialized communication of representatives of different target audiences. Moreover, in the modern intercultural specialized communication there appeared a tendency to use brands names adapted for the Romanian market instead of words denoting types of shoes. Key words: terminology of accessories and fashion, polysemy, cross-cultural borrowing, eponymic terms, syntactic transformations, terminological equivalent. CZU 811.111:685.3 Introduction Phenomena and concepts of the modern world spread across all countries and continents at tremendous speed, despite state borders, level of development of state economy, languages and cultures. To make the intercultural communication faster and more comfortable languages of international communication are involved, their implication having a gradual character on the basis of modern means of their distribution. -

On a Pedestal. from Renaissance Chopines to Baroque Heels ; [Exhibition Held at the Bata Shoe Museum, Toronto, Ont., Nov

Semmelhack, Elizabeth (Hrsg.): On a pedestal. From Renaissance chopines to Baroque heels ; [exhibition held at the Bata Shoe Museum, Toronto, Ont., Nov. 18, 2009 - Sept. 20, 2010], Toronto: Bata Shoe Museum 2009 ISBN-13: 978-0-921638-20-9, 115 S On a Pedestal. From Renaissance Chopines to Baroque Heels Bata Shoe Museum, Toronto, Nov 18, 2009–Sep 20, 2010 Reviewed by: Murray Colin A., Toronto The Bata Shoe Museum opened in Toronto in 1995 as the brainchild of Sonja Bata of the Bata Shoe Company. With a collection of 12,000 objects, this unique museum is dedicated exclusively to the history of the shoe and has a history of informative exhibitions on specialized topics, such as the one currently on display, “On A Pedestal: From Renaissance Chopines to Baroque Heels.” Curated by Elizabeth Semmelhack, this exhibition showcases 50 shoes of the sixteenth and seven- teenth centuries, all of which were designed to elevate the stature of the wearer [1]. The chopine, most popular in Spain and Italy in the sixteenth century, is a kind of platform shoe made of wood or cork and covered in leather or textile. The heeled shoe, in which the heel is built up in height independently of the sole (unlike the blocky or columnar soles of the chopine) was worn by men and women and was most popular in Northern Europe in the seventeenth century. Bringing together this many examples of a select type of shoe in one place is no small achievement, as they had to be borrowed from institutions in Italy, Spain, Austria, Sweden, the United States, the UK, and Canada. -

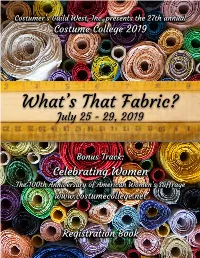

What's That Fabric?

Costumer’s Guild West, Inc. presents the 27th annual Costume College 2019 What’s That Fabric? July 25 - 29, 2019 Bonus Track: Celebrating Women The 100th Anniversary of American Women’s Suffrage www.costumecollege.net Registration Book Contents Dean’s Message 1 Hotel & Local Business Information Special Announcement 2 Warner Center Marriott Woodland Hills 2 Parking at the Hotel 2 Transportation 3 Disability Accommodations 3 Finding Food: light snacks to extravagant meals 4 Emergency Costume Supplies 4 Bringing your own food 5 What to Wear 5 Open to the Public Information Desk 6 Sewing Machine Rental 6 Costume Exhibits 7 Caught on Camera 8 Marketplace 9 CGW Board Mixer 10 Social Media 10 Scholarships & How to Get Them 11 Volunteers 11 Attendees Only Event Check-In 12 Guest Teacher Q+A 12 Panic Room 13 Mobile App 13 Portrait Studio 14 Hospitality Suite 15 Welcome Party: Garments of the Galaxy 16 Friday Night Showcase: Presented by the USO 17 Red Carpet 18 Raffles 18 Time Traveler’s Gala: Opulent Streets of Venice 19 Bargain Basement 20 Sunday Breakfast: Good Mourning 21 Fantasy Tea: Tea at the Haunted Manor 22 Trunk Show 23 Classes Tours 24 Guest Teachers 27 Freshman Orientation 28 Class Information 28 Classes 30 Teachers Teacher Biographies 59 About Costumer’s Guild West & Costume College History of Deans & Themes 73 About Costumer’s Guild West and Costume College 74 Legal Disclosures and Policies 74 Costume College Committee Members 76 CGW, Inc. Board Members 77 All images in this book, other than those provided by Costume College and its teachers, are provided by Shutterstock. -

Fashion,Costume,And Culture

FCC_TP_V3_930 3/5/04 3:57 PM Page 1 Fashion, Costume, and Culture Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages FCC_TP_V3_930 3/5/04 3:57 PM Page 3 Fashion, Costume, and Culture Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages Volume 3: European Culture from the Renaissance to the Modern3 Era SARA PENDERGAST AND TOM PENDERGAST SARAH HERMSEN, Project Editor Fashion, Costume, and Culture: Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages Sara Pendergast and Tom Pendergast Project Editor Imaging and Multimedia Composition Sarah Hermsen Dean Dauphinais, Dave Oblender Evi Seoud Editorial Product Design Manufacturing Lawrence W. Baker Kate Scheible Rita Wimberley Permissions Shalice Shah-Caldwell, Ann Taylor ©2004 by U•X•L. U•X•L is an imprint of For permission to use material from Picture Archive/CORBIS, the Library of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of this product, submit your request via Congress, AP/Wide World Photos; large Thomson Learning, Inc. the Web at http://www.gale-edit.com/ photo, Public Domain. Volume 4, from permissions, or you may download our top to bottom, © Austrian Archives/ U•X•L® is a registered trademark used Permissions Request form and submit CORBIS, AP/Wide World Photos, © Kelly herein under license. Thomson your request by fax or mail to: A. Quin; large photo, AP/Wide World Learning™ is a trademark used herein Permissions Department Photos. Volume 5, from top to bottom, under license. The Gale Group, Inc. Susan D. Rock, AP/Wide World Photos, 27500 Drake Rd. © Ken Settle; large photo, AP/Wide For more information, contact: Farmington Hills, MI 48331-3535 World Photos. -

Actes Des Congrès De La Société Française Shakespeare

Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare 39 | 2021 Shakespeare et les acteurs Performing Genre: Tragic Curtains, Tragic Walking and Tragic Speaking Tiffany Stern Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/shakespeare/5904 DOI: 10.4000/shakespeare.5904 ISSN: 2271-6424 Publisher Société Française Shakespeare Electronic reference Tiffany Stern, “Performing Genre: Tragic Curtains, Tragic Walking and Tragic Speaking”, Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare [Online], 39 | 2021, Online since 19 May 2021, connection on 23 August 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/shakespeare/5904 ; DOI: https://doi.org/ 10.4000/shakespeare.5904 This text was automatically generated on 23 August 2021. © SFS Performing Genre: Tragic Curtains, Tragic Walking and Tragic Speaking 1 Performing Genre: Tragic Curtains, Tragic Walking and Tragic Speaking Tiffany Stern 1 In his New World of English Words, Edward Phillips characterises a “Tragedian” as “a writer of […] a sort of Dramatick Poetry […] representing murthers, sad and mournfull actions.”1 He may be picking up on Florio’s New World of Words which had defined a “comedian” as, no surprise, a “writer of comedies.”2 Both seem, now, self-evident as definitions. But Shakespeare, who was, according to these classifications, both a tragedian and a comedian, used those same words in a different sense. When Rosencrantz lets Hamlet know that “the Tragedians of the City” (Hamlet, TLN 1375) have arrived, or when Cleopatra worries that “The quicke Comedians / Extemporally will -

Stepping Into History at the Bata Shoe Museum Zapatos Y Sociedad: Caminando Por La Historia En El Bata Shoe Museum

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Revistes Catalanes amb Accés Obert Shoes and Society: Stepping into History at the Bata Shoe Museum Zapatos y sociedad: caminando por la historia en el Bata Shoe Museum Elizabeth Semmelhack Senior Curator of the Bata Shoe Museum The Bata Shoe Museum 327, Bloor Street West Toronto (ON), Canadá M5S 1W7 [email protected] Recepción del artículo 19-07-2010. Aceptación de su publicación 17-08-2010 resumen. El Bata Shoe Museum de Toronto (Ca- abstract. The Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto, nadá) es el museo de zapatos más grande de Nor- Canada is the largest shoe museum in North teamérica y alberga una colección de casi trece mil America and houses a collection of nearly 13,000 objetos que abarcan cuatro mil quinientos años de artifacts spanning 4,500 years of history. It is a cen- historia. Es, además, un centro internacional de in- tre for international academic research with a man- vestigación cuyo objetivo es el estudio, la exposi- date to study, exhibit, and publish on the cultural, ción y la publicación de trabajos académicos y cien- historical and sociological significance of footwear. tíficos sobre el significado cultural, histórico y -so The museum opened its doors to the public on ciológico del calzado. El museo abrió sus puertas May 6, 1995 and was established by Mrs. Sonja Bata al público el 6 de mayo de 1995 y fue fundado por as an independent, non-profit institution to house Sonja Bata como una institución independiente y and exhibit her renowned personal collection of sin ánimo de lucro cuya función primordial era al- historic and ethnographic footwear. -

ICOM Costume News 2007:2

ICOM Costume News 2007:2 ICOM Costume News 2007:2 October 20, 2007 INTERNATIONAL COSTUME COMMITTEE COMITÉ INTERNATIONAL DU COSTUME Remarks from the new Chair In order to send out this Newsletter as quickly as possible – and to keep this Newsletter from becoming too large – The wonderful and inspiring meeting in Vienna the Objectives have not yet been translated into French was a perfect send-off for the Committee’s new and Spanish. We will include them in the next Board, with three former Chairmen present: Ann Newsletter and/or send them out separately. Coleman, Mariliina Perkko and Joanna Marschner. Their dedication developed the Committee to what it is today, and our Afin de pouvoir envoyer Nouvelles du Costume le plus remarkable meetings are proof that their efforts vite possible – et pour restreindre le nombre des pages – have paid off. I’m proud and honored to head les Projets d’action de la nouvelle direction n’ont pas up the Committee’s new Board, which encore été traduit ni en francais ni en éspagnol. Le texte represents a fine spectrum of experience in the va être inclu dans le prochain numéro ou envoyé field of costume. séparément. As you will see in this Newsletter, we have decided to present a number of objectives on Con el objetivo de despachar esta Informativo lo más which we will concentrate in this three-year rápido posible – y para que esta Informativo no se period. Please read them carefully and be sure to extienda demasiado – los Objetivos todavía no han sido send your comments and suggestions. -

Quest Spelling List 1 Abacillary Abandonedly Abduction Abhorred

Quest Spelling List abacillary adherend allusion anhedonia abandonedly adiabatic allusively animadversion abduction adios alphanumerical animadversions abhorred adjournment alternative animus abide adjudication altigraph ankylosaur Abidjan admeasurement altocumulus annelid abience admirer altricial annexation ablation admiringly alveolar announcer ablaze admonish always annularity ablutions adobe alyssum ansa abnegation adolescent amalgamation antagonist abnormal adrenergic amandine antennae aboard adustiosis amaranth antepenultimate abolitionists advantageously amateurish anthesis abranchiate advection Amazon anthophorous absentmindedly adventitious ambidexterity anthracite absolutely adversaries amble anthropologist Abyssinian aerophone ambrette anthropology academe aeroplankton amenities anthropomorphic academician Aesculapian amercement anthropophagous acanthus affectation amethysts anthropopsychism acarian affenpinscher amiably anticlimax acceded affix amigo anticoagulant accentuate affliction ammoniacal antidotal accompaniment affrighted amnesty antigen accosted afghan amorphous antihistamine accouchement Afrikaans ampere antinomy accountant afterglow ample antipathies accretionary agalloch ampliate antiphonal acculturation agathism amplitude anxieties accumbent aggrandizing amyotonia anxiolytic accustomed aggressor amyotrophic anxiously acetaldehyde aggrieved anacoluthon aparejo acetaminophen agility anacreontic apiculture acetic agitation anadiplosis apocalyptic acetone agnomen anadromous apocrypha acharya agonize analyze Apollonian -

The Platform Shoe History and Post WWII

The Platform Shoe – History and Post WWII By Martha Rucker Cave drawings from more than 15,000 years ago show humans with animal skins or furs wrapped around their feet. Shoes, in some form or another, have been around for a very long time. The evolution of foot coverings, from the sandal to present-day athletic shoe continues. Platform shoes (also known as Disco Boots) are shoes, boots, or sandals with thick soles at least four inches in height, often made of cork, plastic, rubber, or wood. Wooden-soled platform shoes are technically also known as clogs. They have been worn in various cultures since ancient times for fashion or for added height After their use in Ancient Greece for raising the height of important characters in the Greek theatre and their similar use by high-born prostitutes or courtesans in Venice in the 16th Century, platform shoes are thought to have been worn in Europe in the 18th century to avoid the muck of urban streets. Of the same practical origins are the Japanese geta, a form of traditional Japanese footwear that resembles both clogs and flip-flops There may also be a connection to the buskins of Ancient Rome, which frequently had very thick soles to give added height to the wearer. During the Qing Dynasty, aristocrat Manchu women wore a form of platform shoe similar to 16th century Venetian chopine, a type of women's platform shoe that was popular in the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries which were used to protect the shoes and dress from mud and street soil. -

Aalost Aardvark Aardwolf Aarhus Abadan Abampere Abandon

优质域名注册参考:热门单词 aalost abelia ableism abreast abstract acaridae accusing achiever aconitum actinal aardvark abelmosk ablism abridge abstruse acarina accusive achillea acorea acting aardwolf aberdare abloom abridged absurd acarine acedia aching acores actinia aarhus aberrant ablution abridger absurdly acarpous acentric achira acousma actinian abadan aberrate abnaki abroach abukir acarus acephaly acholia acoustic actinic abampere abetment abnegate abrocoma abulia acaryote acerate achomawi acquire actinide abandon abetter abnormal abrocome abulic acaudal acerbate achras acquired actinism abashed abettor aboard abrogate abundant acaudate acerbic achromia acquirer actinium abasia abeyance abolish abronia abused accede acerbity achromic acquit actinoid abasic abeyant abomasal abrupt abuser accented acerola achylia acragas actinon abatable abfarad abomasum abruptly abusive accentor acerose acicula acreage actitis abatic abhenry aborad abruzzi abutilon accepted acervate acicular acridid actium abating abhorrer aboral abscess abutment acceptor acetal acidemia acridity activase abatis abidance aborning abscise abutter acclaim acetate acidic acrilan actively abattis abiding abortion abscissa abutting accolade acetic acidify acrimony activism abattoir abience abortive abscond abvolt accost acetify acidity acrocarp activist abaxial abient abortus abseil abwatt accouter acetone acidosis acrodont actress abbacy abject aboulia abseiler abydos accoutre acetonic acidotic acrogen actually abbatial abjectly aboulic absentee abysmal accredit acetose aciduric -

The Association of Dress Historians Annual New Research in Dress History Conference: a Weeklong “Festival” of Dress History

The Association of Dress Historians Annual New Research in Dress History Conference: A Weeklong “Festival” of Dress History 7–13 June 2021 Convened By: The Association of Dress Historians www.dresshistorians.org Conference Webpage: www.dresshistorians.org/june2021conference Conference Tickets: https://tinyurl.com/June2021 Conference Email Contact: [email protected] The Association of Dress Historians Annual New Research in Dress History Conference, 7–13 June 2021 The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) supports and promotes the study and professional practice of the history of dress, textiles, and accessories of all cultures and regions of the world, from before classical antiquity to the present day. The ADH is proud to support scholarship in dress and textile history through its international conferences, the publication of The Journal of Dress History, monetary awards for students and researchers, and ADH members’ events such as curators’ tours. The ADH is passionate about sharing knowledge. The mission of the ADH is to start conversations, encourage the exchange of ideas, and expose new and exciting research. If you are not yet an ADH member, please consider joining us! Membership has its perks and is only £10 per year. Thank you for supporting our charity and the work that we do. Memberships are available for purchase on this page: www.dresshistorians.org/membership. To attend the weeklong “festival” of dress history, just one conference ticket must be purchased (which entitles participation at all seven conference days) in advance, here: https://tinyurl.com/June2021. Please join The Association of Dress Historians twitter conversation @DressHistorians, and tweet about our June 2021 New Research conference with hashtags #ADHNewResearch2021 and #NewResearchFestival.