Western Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bankside Power Station: Planning, Politics and Pollution

BANKSIDE POWER STATION: PLANNING, POLITICS AND POLLUTION Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Stephen Andrew Murray Centre for Urban History University of Leicester 2014 Bankside Power Station ii Bankside Power Station: Planning, Politics and Pollution Stephen Andrew Murray Abstract Electricity has been a feature of the British urban landscape since the 1890s. Yet there are few accounts of urban electricity undertakings or their generating stations. This history of Bankside power station uses government and company records to analyse the supply, development and use of electricity in the City of London, and the political, economic and social contexts in which the power station was planned, designed and operated. The close-focus adopted reveals issues that are not identified in, or are qualifying or counter-examples to, the existing macro-scale accounts of the wider electricity industry. Contrary to the perceived backwardness of the industry in the inter-war period this study demonstrates that Bankside was part of an efficient and profitable private company which was increasingly subject to bureaucratic centralised control. Significant decision-making processes are examined including post-war urban planning by local and central government and technological decision-making in the electricity industry. The study contributes to the history of technology and the environment through an analysis of the technologies that were proposed or deployed at the post-war power station, including those intended to mitigate its impact, together with an examination of their long-term effectiveness. Bankside made a valuable contribution to electricity supplies in London until the 1973 Middle East oil crisis compromised its economic viability. -

The Speaker of the House of Commons: the Office and Its Holders Since 1945

The Speaker of the House of Commons: The Office and Its Holders since 1945 Matthew William Laban Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2014 1 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY I, Matthew William Laban, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of this thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: Details of collaboration and publications: Laban, Matthew, Mr Speaker: The Office and the Individuals since 1945, (London, 2013). 2 ABSTRACT The post-war period has witnessed the Speakership of the House of Commons evolving from an important internal parliamentary office into one of the most recognised public roles in British political life. This historic office has not, however, been examined in any detail since Philip Laundy’s seminal work entitled The Office of Speaker published in 1964. -

Parliamentary Private Secretaries to Prime Ministers Since 1906 Prime Minister Parliamentary Private Secretary Notes

BRIEFING PAPER Number 06579, 11 March 2020 Parliamentary Private Compiled by Secretaries to Prime Sarah Priddy Ministers since 1906 This List notes Parliamentary Private Secretaries to successive Prime Ministers since 1906. Alex Burghart was appointed PPS to Boris Johnson in July 2019 and Trudy Harrison appointed PPS in January 2020. Parliamentary Private Secretaries (PPSs) are not members of the Government although they do have responsibilities and restrictions as defined by the Ministerial Code available on the Cabinet Office website. A list of PPSs to Cabinet Ministers as at June 2019 is published on the Government’s transparency webpages. It is usual for the Leader of the Opposition to have a PPS; Tan Dhesi was appointed as Jeremy Corbyn’s PPS in January 2020. Further information The Commons Library briefing on Parliamentary Private Secretaries provides a history of the development of the position of Parliamentary Private Secretary in general and looks at the role and functions of the post and the limitations placed upon its holders. The Institute for Government’s explainer: parliamentary private secretaries (Nov 2019) considers the numbers of PPSs over time. www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Parliamentary Private Secretaries to Prime Ministers since 1906 Prime Minister Parliamentary Private Secretary Notes Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman (1905-08) Herbert Carr-Gomm 1906-08 Assistant Private Secretary Herbert Asquith (1908-16) 1908-09 Vice-Chamberlain of -

Official Journal of the European Communities

Official Journal of the European Communities Volume 19 No C 259 4 November 1976 English Edition Information and Notices Contents I Information European Parliament 1976/77 session Minutes of the sitting of Monday, 11 October 1976 1 Adoption of the agenda 9 Minutes of the sitting of Tuesday, 12 October 1976 10 Resolution on the Friuli earthquake 11 Resolution on the further consultation of the European Parliament on proposals amended or withdrawn by the Commission 12 Resolution on the preparation, conduct and outcome of the fourth United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (5—31 May 1976) 13 Opinion on the Cooperation Agreements concluded between the European Economic Community and — the Republic of Tunisia — the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria — the Kingdom of Morocco 15 Resolution on the report of the Commission on the protection of fundamental rights 17 Minutes of the sitting of Wednesday, 13 October 1976 19 Question Time Questions to the Council No 1 by Mr Hamilton: Uranium price-fixing by certain companies in Member States ... 19 No 2 by Mr Caro: Election of the European Parliament by direct universal suffrage 19 No 3 by Sir Geoffrey de Freitas: Seat of the new directly elected European Parliament ... 19 No 4 by Mr Berkhouwer: EEC—COMECON relations 20 No 5 by Mr Fletcher: Public admittance to legislative meetings of the Council 20 No 6 by Mrs Dunwoody: Delay in accrediting the Fiji Ambassador to the Community 20 No 7 by Mr Gibbons: Monetary compensatory amounts 20 2 (Continued overleaf) Contents (continued) Questions -

The NATO Parliamentary Assembly and UK Delegations

BRIEFING PAPER Number CBP 8951, 5 November 2020 The NATO Parliamentary By Nigel Walker Assembly and UK delegations Contents: 1. Summary 2. UK delegations 3. Appendix 1: Alphabetical list of UK delegates 1955-present www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 The NATO Parliamentary Assembly and UK delegations Contents 1. Summary 3 1.1 NATO Parliamentary Assembly in brief 3 1.2 The UK Delegation 6 2. UK delegations 8 2.1 2019-2024 Parliament 9 2.2 2017-2019 Parliament 10 2.3 2015-2017 Parliament 11 2.4 2010-2015 Parliament 12 2.5 2005-2010 Parliament 13 2.6 2001-2005 Parliament 14 2.7 1997-2001 Parliament 15 2.8 1992-1997 Parliament 16 2.9 1987-1992 Parliament 17 2.10 1983-1987 Parliament 18 2.11 1979-1983 Parliament 19 2.12 Oct1974-1979 Parliament 20 2.13 Feb-Oct 1974 Parliament 21 2.14 1970- Feb1974 Parliament 22 2.15 1966-1970 Parliament 23 2.16 1964-1966 Parliament 24 2.17 1959-1964 Parliament 25 2.18 1955-1959 Parliament 26 3. Appendix 1: Alphabetical list of UK delegates 1955- present 28 Cover page image copyright: Image 15116584265_f2355b15bb_o, NATO Parliamentary Assembly Pre-Summit Conference in London, 2 September 2014 by Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) – Flickr home page. Licensed by Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) license/ image cropped. 3 Commons Library Briefing, 5 November 2020 1. Summary Since being formed in 1965, the NATO Parliamentary Assembly has provided a forum for parliamentarians from the NATO Member States to promote debate on key security challenges, facilitate mutual understanding and support national parliamentary oversight of defence matters. -

Denbighshire Record Office

GB 0209 DD/DM/698 Denbighshire Record Office This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 34291 The National Archives CLWYD RECORD OFFICE Schedule of records deposited on indefinite loan by J.O.Jones, Rhydonnen, Ruthin Road, Mold on 13 August 1986. (A.N.1419). Ref: DD/DM/698 James Idwal Jones (1900-82) James Idwal Jones represented the Wrexham constituency in Parliament for the Labour.Party from 1955 until his retirement in 1970. The son of a Rhos miner, he became active in politics from an early age. He was educated at Ruabon Grammar School and Bangor Normal College, later gaining the BSc Economics degree of London University. He taught in Rhos from 1928 onwards becoming headmaster of Grango School in 1938. He was defeated as the Labour candidate for the Denbigh Division in the 1951 election. As MP for Wrexham, J.I.Jones was concerned, amongst other things, with the setting up of the industrial estate, and the permanent establishment of Cartrefle College. These and his many interests including education, the Welsh language and affairs, the creation of employment opportunities, are all well represented in his papers. His brother T.W.Jones, later Lord Maelor, was Labour MP for Merioneth for the period 1951-66. He was a prolific contributor of articles to the press, many are in the collection. He was author of a number of books including the first historical atlas of Wales, published in 1952. His records were deposited by his son, Assistant Director of Education for the county of Clwyd. -

The North Atlantic Assembly 1964-1974

THE NORTH ATLANTIC ASSEMBLY 1964-1974 Introduction by Geoffrey de Freitas Member of Parliament Published in English and French by The British Atlantic Committee 36 Craven Street, London WC2N 5NG THE NORTH ATLANTIC ASSEMBLY 1964-19 74 Introduction by Geoffrey de Freitas Member of Parliament Published in English and French by The British Atlantic Committee 36 Craven Street, London WC2N 5NG THE NORTH ATLANTIC ASSEMBLY 1964-1974 by Fraser CAMERON "The world we, in the West, build may depend less on technical discus• sions than on common dreams". Henry KISSINGER "We must show that the North Atlantic Assembly is not merely a club or a glorified debating society". President Kasim GULEK PREFACE The North Atlantic Assembly - until 1966 known as the NATO Parliamentarians' Conference — celebrates its twentieth anniversary in 1974. The only forum where parliamentarians from both sides of the Atlantic meet regularly to discuss issues of common interest, the North Atlantic Assembly has made considerable progress since its foundation in the mid 1950s. On the initiative of distinguished parliamentarians from both Europe and North America, arrangements were made to hold a conference of members of Parliaments from the fifteen member countries of the Atlantic Alliance. This conference met in Paris, at the Palais de Chaillot, from 18-23 July, 1955. Although an unofficial body with no statutory powers, the Conference served from 1955 onwards as an important platform for discussions between parlia• mentary delegates from all NATO countries. During its first ten years of existence, the Conference held regular annual meetings, established a comprehensive committee system, arranged military tours for delegates and moved its Secretariat from London in order to be close to NATO headquarters in Paris. -

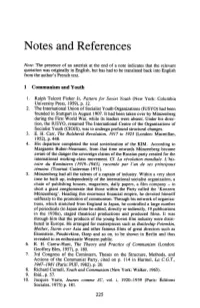

Notes and References

Notes and References Note: The presence of an asterisk at the end of a note indicates that the relevant quotation was originally in English, but has had to be translated back into English from the author's French text. 1 Communism and Youth I. Ralph Talcott Fisher Jr, Pattern for Soviet Youth (New York: Columbia University Press, 1959), p. 12. 2. The International Union of Socialist Youth Organizations (IUSYO) had been founded in Stuttgart in August 1907. It had been taken over by Miinzenberg during the First World War, while its leaders were absent. Under his direc tion, the IUS YO, renamed The International Centre of the Organizations of Socialist Youth (CIOJS), was to undergo profound structural changes. 3. E. H. Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution, 1917 to 1923 (London: Macmillan, 1952), p. 448. 4. His departure completed the total sovietization of the KIM. According to Margarete Huber-Neumann, from that time onwards Miinzenberg became aware of the danger the sovereign claims of the Russian party created for the international working-class movement. Cf. La revolution mondiale. L'his toire du Komintern ( 1919-1943), racontee par l'un de ses principaux temoins (Tournai: Casterman 1971). 5. Miinzenberg had all the talents of a captain of industry. Within a very short time he built up, independently of the international socialist organization, a chain of publishing houses, magazines, daily papers, a film company - in short a giant conglomerate that those within the Party called the 'Konzern Miinzenberg'. Heading this enormous financial empire, he devoted himself selflessly to the promotion of communism. Through his network of organiza tions, which stretched from England to Japan, he controlled a large number of periodicals (in Japan alone he edited, directly or indirectly, 19 publications in the 1930s), staged theatrical productions and produced films. -

Labour to Ta~<E Par~Uament Seats

No. 16 July 1975 It was clearly the Community's duty, as Conserva • tive leader Peter Kiri< pointed out, to give aid to Labour to ta~<e Par~uament seats Portugal "in the cata;;trophic economic conditions in which she finds herself". It was equally clearly .wo and a half years of boycott will come to an end on July 7 when 18 Labo.,r Members will take right "that we should not interfere in the internal their seats ir. the European Parliament. affairs of anvther country". Bu! a point might European Parliament President Georges Spenale (Soc/F) on June 19 welcomed the Labour decision come at whici, there would have to be cond:tions. to name a delegation and to join the Socialist Group. The strengthening of the Parliament to its full For almost all speakers, including Commissioner complement of 198 Members would lead to its enrichment as had happened in 1973 when the first Sir Christopher Soames, those c<'nditions were British, Irish and Danish MPs had arrived. "the establishment in Portugal of a pluralist democracy". Socialist Group leader Ludwig Fellermaier (Ger European Progressive Democrats (17) and the Though everyone, however, was agreed on the many) said of the referendum result: "The British Communists (15)? Will other realignments take gravity of economic conditions in Portugal - have demonstrated their proverbial commonsense". place? 270,000 unemployed, 30% inflation and zero With its Labour friends, the Socialist Group will But at Westminster the nomination of the investment - there were differences on the polit continue its work towards the democratic develop Labour Members did not come about smoothly. -

British Policy Towards Kenya, 1960-1980

Durham E-Theses `Kenya is no doubt a special case':British policy towards Kenya, 1960-1980 CULLEN, CATRIONA,POPPY How to cite: CULLEN, CATRIONA,POPPY (2015) `Kenya is no doubt a special case':British policy towards Kenya, 1960-1980, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11180/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ‘Kenya is no doubt a special case’: British policy towards Kenya, 1960-1980 Poppy Cullen Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Durham University 2015 Abstract ‘Kenya is no doubt a special case’: British policy towards Kenya, 1960-1980 Poppy Cullen This thesis examines the ways British policy towards Kenya was made from 1960 to 1980 – from the last years of British colonial rule and through the first two decades of Kenya’s existence as an independent state. -

148868291.Pdf

t· •.•·•.· .•·....... ·.· l.. ' "'. R ,I I CONTENTS The week 3 Green light for European elections . 3 Uproar over margarine tax . 8 The acceptable face of competition 11 Drought and the cost of living 14 Community research has a future (but no bets on JET yet) . 15 Agreement with Canada welcomed . 16 Joint meeting with Cou~cil of Europe . 18 Helping the hungry . 24 Question Time 25 Summary of the week . 28 References . 33 Abbreviations . 34 Postscript - European elections : the decision and the act signed by the Nine Foreign Ministers in Brussels on September 20th. 34 -1- SESSION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 1976- 1977 Sittings held in Luxembourg Monday 13 September to Friday 17 September 1976 The Week The good news this week was Laurens Jan Brinkhorst's announcement that the Nine Foreign Ministers would sign a decision (spelling out a date) and and act (spelling out a commitment) on European elections at their meeting in Brussels on September 20th. This still leaves open the question of ratification (where necessacy) by national parliaments and that of legislating to organize the elections themselves, hopefully for May or June 1978. But there is some optimism that all this can be done in time. The other main issues arising this week were research, the drought and its aftermath, the proposed vegetable oils tax, competition and what can be learned from the Seve so disaster. Green light for European elections Laurens Jan Brinkhorst, Dutch Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs and current President of the Community's decision-taking Council of Ministers, told the European Parliament on September 15th that the Council would take the final decision on European elections when it met in Brussels on September 20th. -

Official Journal of the European Communities

Official Journal of the European Communities Volume 20 No C 272 11 November 1977 English Edition Information and Notices Contents I Information Consultative Assembly of the Agreement between the African, Caribbean and Pacific States and the European Economic Community Minutes of the sitting of Wednesday, 8 June 1977 1 Minutes of the sitting of Thursday, 9 June 1977 8 Minutes of the sitting of Friday, 10 June 1977 8 1 11. 11. 77 Official Journal of the European Communities No C 272/1 I (Information) CONSULTATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE AFRICAN, CARIBBEAN AND PACIFIC STATES AND THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC COMMUNITY European Centre, Kirchberg — Luxembourg MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS OF THE SITTING OF WEDNESDAY, 8 JUNE 1977 IN THE CHAIR: Mr Philippe YACfi President of the National Assembly of the Republic of the Ivory Coast The sitting was opened at 9.05 a.m. Election of the Bureau Pursuant to Article 6 (1) of the Rules of Procedure the Opening of the second meeting of the Assembly Assembly elected its Bureau, which would consist of the following 12 Members: President Yace declared the second meeting of the Assembly open. Presidents: Mr Yace and Mr Colombo Membership of the Assembly Vice-Presidents: Mr Muna Mr Spenale Pursuant to Article 1 (2) of the Rules of Procedure Mrs Mathe Miss Flesch President Yace informed the Assembly of the compo- Mr Adriko Mr de la Malene sition of the Assembly. Mr Wijntuin Lord Reay Mr Philipps Mr Sandri The list of Members of the Assembly is appended to the minutes (Annex I). Agenda President Yace said that the representatives of the Cape Verde Islands, Papua New Guinea and Sao Tome and On a proposal from the Joint Committee, the Assembly Principe were attending as observers (Annex II).