Ghana and the West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Europe

Western Europe GREAT BRITAIN ix years of Socialist rule came to an end at the General Election of Octo- S ber 25, 1951. Britain, however, expressed only a narrow preferment for the Conservative Party and Prime Minister Winston Churchill's administra- tion had a lead of only sixteen seats in the House of Commons, as compared with Labor's rule during the preceding twenty months with a majority of six. Political commentators had foretold a landslide for the Conservative Party but Labor retained a plurality of the total votes cast. As in previous years, domestic issues were most persistent in the campaign; but while the cost of living and the housing problem were the dominant issues, the loss of prestige suffered by Britain in the Middle East as a result of the dispute with Iran and the denunciation by Egypt of its 1936 treaty with Great Britain were undoubtedly factors in terminating the Socialist regime. In its attitude to Germany and Western Europe, Conservative policy did not radically vary from its predecessor's, promising only limited participation in any scheme for European unity. The Labor Party voted against ratification of the Contrac- tual Agreement with the Bonn Government in July 1952 on the grounds that this agreement was premature, offering Germany rearmament that would per- manently divide the country and sharpen divisions with Russia before all possibilities of German unification had been explored. Nor was the Labor Party satisfied that Chancellor Konrad Adenauer had the full backing of the West German people. Issues affecting the Jews were absent from the 1951 election, and only a few minor anti-Semitic manifestations occurred during the campaign. -

A Pre-Election Assessment Report June 1, 1992

A V InternationalFoundation for Electoral Systems 1620 I STREET, N.W. *SUITE6, ,vWASHINGTON, D.C. 20006. (202)828-8507 - FAX (202)452-0804 (202) 785-1672 GHANA: A PRE-ELECTION ASSESSMENT REPORT JUNE 1, 1992 Laurie A. Cooper Fred M. Hayward Anthony W.J. Lee This report was made possible by a grant from the U.S. Agency for International Development. This material is in the public domain and may be reproduced without permission; citation of IFES as the source would be - appreciated. BOARD OF F.Clifton White Patricia Hutar James M. Cannon David Jones Randa Teague DIRECTORS Chairman C. Secretary Counsel Richard M. Scammon Joseph Napolitan Charles Manatt John C.White Richard W.Soudriette Vice Chairman Treasurer Robert C.Walker Director TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................... 1 I. INTRODUCTION ........................................ 3 II. BACKGROUND TO THE DEMOCRATIZATION PROCESS .............. 5 Economic and Infrastructural Background ......................... 5 Political Background ...................................... 6 The New Constitution ..................................... 9 National Commission for Democracy .......................... 9 Committee of Experts ................................... 10 National Consultative Assembly .............................. 10 The Constitution ....................................... 11 Civil Liberties .... .................................... 12 III. ELECTION POLICIES AND PROCEDURES ...................... 14 Referendum Observations .................................. -

Bankside Power Station: Planning, Politics and Pollution

BANKSIDE POWER STATION: PLANNING, POLITICS AND POLLUTION Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Stephen Andrew Murray Centre for Urban History University of Leicester 2014 Bankside Power Station ii Bankside Power Station: Planning, Politics and Pollution Stephen Andrew Murray Abstract Electricity has been a feature of the British urban landscape since the 1890s. Yet there are few accounts of urban electricity undertakings or their generating stations. This history of Bankside power station uses government and company records to analyse the supply, development and use of electricity in the City of London, and the political, economic and social contexts in which the power station was planned, designed and operated. The close-focus adopted reveals issues that are not identified in, or are qualifying or counter-examples to, the existing macro-scale accounts of the wider electricity industry. Contrary to the perceived backwardness of the industry in the inter-war period this study demonstrates that Bankside was part of an efficient and profitable private company which was increasingly subject to bureaucratic centralised control. Significant decision-making processes are examined including post-war urban planning by local and central government and technological decision-making in the electricity industry. The study contributes to the history of technology and the environment through an analysis of the technologies that were proposed or deployed at the post-war power station, including those intended to mitigate its impact, together with an examination of their long-term effectiveness. Bankside made a valuable contribution to electricity supplies in London until the 1973 Middle East oil crisis compromised its economic viability. -

The Speaker of the House of Commons: the Office and Its Holders Since 1945

The Speaker of the House of Commons: The Office and Its Holders since 1945 Matthew William Laban Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2014 1 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY I, Matthew William Laban, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of this thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: Details of collaboration and publications: Laban, Matthew, Mr Speaker: The Office and the Individuals since 1945, (London, 2013). 2 ABSTRACT The post-war period has witnessed the Speakership of the House of Commons evolving from an important internal parliamentary office into one of the most recognised public roles in British political life. This historic office has not, however, been examined in any detail since Philip Laundy’s seminal work entitled The Office of Speaker published in 1964. -

Parliamentary Private Secretaries to Prime Ministers Since 1906 Prime Minister Parliamentary Private Secretary Notes

BRIEFING PAPER Number 06579, 11 March 2020 Parliamentary Private Compiled by Secretaries to Prime Sarah Priddy Ministers since 1906 This List notes Parliamentary Private Secretaries to successive Prime Ministers since 1906. Alex Burghart was appointed PPS to Boris Johnson in July 2019 and Trudy Harrison appointed PPS in January 2020. Parliamentary Private Secretaries (PPSs) are not members of the Government although they do have responsibilities and restrictions as defined by the Ministerial Code available on the Cabinet Office website. A list of PPSs to Cabinet Ministers as at June 2019 is published on the Government’s transparency webpages. It is usual for the Leader of the Opposition to have a PPS; Tan Dhesi was appointed as Jeremy Corbyn’s PPS in January 2020. Further information The Commons Library briefing on Parliamentary Private Secretaries provides a history of the development of the position of Parliamentary Private Secretary in general and looks at the role and functions of the post and the limitations placed upon its holders. The Institute for Government’s explainer: parliamentary private secretaries (Nov 2019) considers the numbers of PPSs over time. www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Parliamentary Private Secretaries to Prime Ministers since 1906 Prime Minister Parliamentary Private Secretary Notes Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman (1905-08) Herbert Carr-Gomm 1906-08 Assistant Private Secretary Herbert Asquith (1908-16) 1908-09 Vice-Chamberlain of -

Democracy Watch 6 & 7

Democracy Watch Vol. 2, No. 2&3 April-September 2001 1 A Quarterly Newsletter of the Ghana Center for Democratic Development 6&7 DemocracyWatch 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789 statements. The openness to the media Volume 2, No. 2&3 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789 was underscored by President Kufuors April-September 2001 The Media in the news conference to mark his first 100 Post Rawlings Era days in office, an event never witnessed ISSN: 0855-417X during the 19 years ex-President Rawlings was in power. A new era of positive government- In this issue media relations? In an early gesture of acknowledging the contribution of the media to Ghanaian Among the media, media watchers, democratic development, the NPP and observers of Ghanaian politics, government decided to abort ongoing EThe Media in the Post Rawlings Era there is a well-justified feeling of relief state prosecutions against journalists for .................Page 1 and euphoria over the demise of a criminal and or seditious libel. Most media unfriendly-regime. Indeed, it significantly, it has made good on its promise to repeal the obnoxious criminal E The New Challenges in Intra-media was expected that the relationship Relations ............. -

African Liberation and Unity in Nkrumah's Ghana

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/36074 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Grilli, Matteo Title: African liberation and unity in Nkrumah's Ghana : a study of the role of "Pan- African Institutions" in the making of Ghana's foreign policy, 1957 - 1966 Issue Date: 2015-11-03 Introduction Almost sixty years after its fall - occurred in a coup d'état on 24 February 1966 - Nkrumah‟s government in Ghana is still unanimously considered as one of the most influential but also controversial political experiences in the history of modern Africa. Its importance lies undoubtedly in the peculiarities of its internal policies and in the influence it exerted in Africa during the crucial years of the first wave of independence. Several aspects of Nkrumah‟s policy led this small West African country - without any visible strategic relevance – to act as a political giant becoming the torchbearer of Pan-Africanism and socialism in the continent. Between 1957 and 1966, Nkrumah transformed Ghana into a political laboratory where he could actualize his vision, known since 1960 as “Nkrumahism”.i This vision can be summarized as the achievement of three goals: national unity, economic transformation (towards socialism) and Africa‟s total liberation and unity.ii The latter point of Nkrumah‟s political agenda coincided with the actualization of Pan- Africanism and will be defined in this thesis as Ghana‟s Pan-African policy.iii In line with the indications of the 1945 Manchester Pan-African Congress, Nkrumah considered the independence of his country only as the first step towards the liberation and unification of the whole continent. -

Official Journal of the European Communities

Official Journal of the European Communities Volume 19 No C 259 4 November 1976 English Edition Information and Notices Contents I Information European Parliament 1976/77 session Minutes of the sitting of Monday, 11 October 1976 1 Adoption of the agenda 9 Minutes of the sitting of Tuesday, 12 October 1976 10 Resolution on the Friuli earthquake 11 Resolution on the further consultation of the European Parliament on proposals amended or withdrawn by the Commission 12 Resolution on the preparation, conduct and outcome of the fourth United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (5—31 May 1976) 13 Opinion on the Cooperation Agreements concluded between the European Economic Community and — the Republic of Tunisia — the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria — the Kingdom of Morocco 15 Resolution on the report of the Commission on the protection of fundamental rights 17 Minutes of the sitting of Wednesday, 13 October 1976 19 Question Time Questions to the Council No 1 by Mr Hamilton: Uranium price-fixing by certain companies in Member States ... 19 No 2 by Mr Caro: Election of the European Parliament by direct universal suffrage 19 No 3 by Sir Geoffrey de Freitas: Seat of the new directly elected European Parliament ... 19 No 4 by Mr Berkhouwer: EEC—COMECON relations 20 No 5 by Mr Fletcher: Public admittance to legislative meetings of the Council 20 No 6 by Mrs Dunwoody: Delay in accrediting the Fiji Ambassador to the Community 20 No 7 by Mr Gibbons: Monetary compensatory amounts 20 2 (Continued overleaf) Contents (continued) Questions -

The NATO Parliamentary Assembly and UK Delegations

BRIEFING PAPER Number CBP 8951, 5 November 2020 The NATO Parliamentary By Nigel Walker Assembly and UK delegations Contents: 1. Summary 2. UK delegations 3. Appendix 1: Alphabetical list of UK delegates 1955-present www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 The NATO Parliamentary Assembly and UK delegations Contents 1. Summary 3 1.1 NATO Parliamentary Assembly in brief 3 1.2 The UK Delegation 6 2. UK delegations 8 2.1 2019-2024 Parliament 9 2.2 2017-2019 Parliament 10 2.3 2015-2017 Parliament 11 2.4 2010-2015 Parliament 12 2.5 2005-2010 Parliament 13 2.6 2001-2005 Parliament 14 2.7 1997-2001 Parliament 15 2.8 1992-1997 Parliament 16 2.9 1987-1992 Parliament 17 2.10 1983-1987 Parliament 18 2.11 1979-1983 Parliament 19 2.12 Oct1974-1979 Parliament 20 2.13 Feb-Oct 1974 Parliament 21 2.14 1970- Feb1974 Parliament 22 2.15 1966-1970 Parliament 23 2.16 1964-1966 Parliament 24 2.17 1959-1964 Parliament 25 2.18 1955-1959 Parliament 26 3. Appendix 1: Alphabetical list of UK delegates 1955- present 28 Cover page image copyright: Image 15116584265_f2355b15bb_o, NATO Parliamentary Assembly Pre-Summit Conference in London, 2 September 2014 by Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) – Flickr home page. Licensed by Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) license/ image cropped. 3 Commons Library Briefing, 5 November 2020 1. Summary Since being formed in 1965, the NATO Parliamentary Assembly has provided a forum for parliamentarians from the NATO Member States to promote debate on key security challenges, facilitate mutual understanding and support national parliamentary oversight of defence matters. -

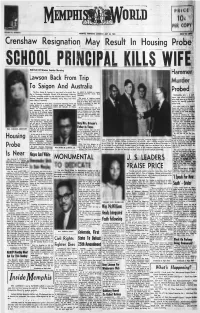

Crenshaw Resignation May Result in Housing Probe

I* » rl fl Memphis XI c MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE, SATURDAY, JULY 24, 1965 PRICE TEN CENTS Crenshaw Resignation May Result In Housing Probe X i ' ! Will Tell Of Mission Sunday Morning Hammer Lawson Back From Trip To Saigon And Australia Probed The Rev. James M. Lawson, Jr. was back in his pulpit Sun he talked to students at Sidney day at Centenary Methodist Church, 878 Mississippi, following University and New South Wale University. TUSCUMBIA, Ala. - A well- a 20-day round-the-world trip that included stops in Paris, Rome, known high school principal .1» Bombay, Bangkok, Saigon, Cambodia, Hong Kong and three The group of religious leaders being held here on a charge of major cities in Australia. spent five days in Saigon and then went on to Hong Kong where they slaying his equally prominent Rev. Mr. Lawson was on a peace in Australia addressing church and drafted a statement on their ob teacher-wife. seeking mission as a member of student groups In Sidney, Mel servations and findings. the Fellowship of Reconciliation bourne and Adelaide. In Sidney, The school head is in Colbert At the beginning of the trip, the through its Clergymen's Emer County jail where he faces first »J American churchmen spent three degree murder charges for the ham*., gency Committee for Viet Nam. days in Bangkok where they mapp mer killing of his mate late last He was one of 12 religious leaders ed their program for Saigon after Thursday night. froming the American team which conferring with government offic was joined by another group from Clinton K. -

Denbighshire Record Office

GB 0209 DD/DM/698 Denbighshire Record Office This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 34291 The National Archives CLWYD RECORD OFFICE Schedule of records deposited on indefinite loan by J.O.Jones, Rhydonnen, Ruthin Road, Mold on 13 August 1986. (A.N.1419). Ref: DD/DM/698 James Idwal Jones (1900-82) James Idwal Jones represented the Wrexham constituency in Parliament for the Labour.Party from 1955 until his retirement in 1970. The son of a Rhos miner, he became active in politics from an early age. He was educated at Ruabon Grammar School and Bangor Normal College, later gaining the BSc Economics degree of London University. He taught in Rhos from 1928 onwards becoming headmaster of Grango School in 1938. He was defeated as the Labour candidate for the Denbigh Division in the 1951 election. As MP for Wrexham, J.I.Jones was concerned, amongst other things, with the setting up of the industrial estate, and the permanent establishment of Cartrefle College. These and his many interests including education, the Welsh language and affairs, the creation of employment opportunities, are all well represented in his papers. His brother T.W.Jones, later Lord Maelor, was Labour MP for Merioneth for the period 1951-66. He was a prolific contributor of articles to the press, many are in the collection. He was author of a number of books including the first historical atlas of Wales, published in 1952. His records were deposited by his son, Assistant Director of Education for the county of Clwyd. -

The North Atlantic Assembly 1964-1974

THE NORTH ATLANTIC ASSEMBLY 1964-1974 Introduction by Geoffrey de Freitas Member of Parliament Published in English and French by The British Atlantic Committee 36 Craven Street, London WC2N 5NG THE NORTH ATLANTIC ASSEMBLY 1964-19 74 Introduction by Geoffrey de Freitas Member of Parliament Published in English and French by The British Atlantic Committee 36 Craven Street, London WC2N 5NG THE NORTH ATLANTIC ASSEMBLY 1964-1974 by Fraser CAMERON "The world we, in the West, build may depend less on technical discus• sions than on common dreams". Henry KISSINGER "We must show that the North Atlantic Assembly is not merely a club or a glorified debating society". President Kasim GULEK PREFACE The North Atlantic Assembly - until 1966 known as the NATO Parliamentarians' Conference — celebrates its twentieth anniversary in 1974. The only forum where parliamentarians from both sides of the Atlantic meet regularly to discuss issues of common interest, the North Atlantic Assembly has made considerable progress since its foundation in the mid 1950s. On the initiative of distinguished parliamentarians from both Europe and North America, arrangements were made to hold a conference of members of Parliaments from the fifteen member countries of the Atlantic Alliance. This conference met in Paris, at the Palais de Chaillot, from 18-23 July, 1955. Although an unofficial body with no statutory powers, the Conference served from 1955 onwards as an important platform for discussions between parlia• mentary delegates from all NATO countries. During its first ten years of existence, the Conference held regular annual meetings, established a comprehensive committee system, arranged military tours for delegates and moved its Secretariat from London in order to be close to NATO headquarters in Paris.