Siddiqi Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Hegemony Over the Heavens: The Chinese and American Struggle in Space by John Hodgson Modinger A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY CENTRE FOR MILITARY AND STRATEGIC STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA AUGUST, 2008 © John Hodgson Modinger 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-44361-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-44361-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Another Global History of Science: Making Space for India and China

BJHS: Themes 1: 115–143, 2016. © British Society for the History of Science 2016. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/bjt.2016.4 First published online 22 March 2016 Another global history of science: making space for India and China ASIF SIDDIQI* Abstract. Drawing from recent theoretical insights on the circulation of knowledge, this article, grounded in real-world examples, illustrates the importance of ‘the site’ as an analytical heur- istic for revealing processes, movements and connections illegible within either nation-centred histories or comparative national studies. By investigating place instead of project, the study reframes the birth of modern rocket developments in both China and India as fundamentally intertwined within common global networks of science. I investigate four seemingly discon- nected sites in the US, India, China and Ukraine, each separated by politics but connected and embedded in conduits that enabled the flow of expertise during (and in some cases despite) the Cold War. By doing so, it is possible to reconstruct an exemplar of a kind of global history of science, some of which takes place in China, some in India, and some else- where, but all of it connected. There are no discrete beginnings or endings here, merely points of intervention to take stock of processes in action. Each site produces objects and knowledge that contribute to our understanding of the other sites, furthering the overall narra- tive on Chinese and Indian efforts to formalize a ‘national’ space programme. -

Evolution of Solid Propellant Rockets in India

EVOLUTION OF SOLID PROPELLANT ROCKETS IN INDIA EVOLUTION OF SOLID PROPELLANT ROCKETS IN INDIA Rajaram Nagappa Former Associate Director Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre Thiruvananthapuram, India Defence Research and Development Organisation Ministry of Defence, New Delhi – 110 011 2014 DRDO MONOGRAPHS/SPECIAL PUBLICATIONS SERIES EVOLUTION OF SOLID PROPELLANT ROCKETS IN INDIA RAJARAM NAGAPPA Series Editors Editor-in-Chief Assoc. Editor-in-Chief Editor Asst. Editor SK Jindal GS Mukherjee Anitha Saravanan Kavita Narwal Editorial Assistant Gunjan Bakshi Cataloguing in Publication Nagappa, Rajaram Evolution of Solid Propellant Rockets in India DRDO Monographs/Special Publications Series. 1. Rocket Fuel 2. Rocket Propellant 3. Solid Propellant I. Title II. Series 621.453:662.3(540) © 2014, Defence Research & Development Organisation, New Delhi – 110 011. ISBN 978-81-86514-51-1 All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the Indian Copyright Act 1957, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted, stored in a database or a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. The views expressed in the book are those of the author only. The Editors or the Publisher do not assume responsibility for the statements/opinions expressed by the author. Printing Marketing SK Gupta Rajpal Singh Published by Director, DESIDOC, Metcalfe House, Delhi – 110 054. To the fond memory of my parents Contents Foreword xi Preface -

IISER AR PART I A.Cdr

dm{f©H$ à{VdoXZ Annual Report 2016-17 ^maVr¶ {dkmZ {ejm Ed§ AZwg§YmZ g§ñWmZ nwUo Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Pune XyaX{e©Vm Ed§ bú` uCƒV‘ j‘Vm Ho$ EH$ Eogo d¡km{ZH$ g§ñWmZ H$s ñWmnZm {Og‘| AË`mYw{ZH$ AZwg§YmZ g{hV AÜ`mnZ Ed§ {ejm nyU©ê$n go EH$sH¥$V hmo& u{Okmgm Am¡a aMZmË‘H$Vm go `wº$ CËH¥$ï> g‘mH$bZmË‘H$ AÜ`mnZ Ho$ ‘mÜ`m‘ go ‘m¡{bH$ {dkmZ Ho$ AÜ``Z H$mo amoMH$ ~ZmZm& ubMrbo Ed§ Agr‘ nmR>çH«$‘ VWm AZwg§YmZ n[a`moOZmAm| Ho$ ‘mÜ`‘ go N>moQ>r Am`w ‘| hr AZwg§YmZ joÌ ‘| àdoe& Vision & Mission uEstablish scientific institution of the highest caliber where teaching and education are totally integrated with state-of-the-art research uMake learning of basic sciences exciting through excellent integrative teaching driven by curiosity and creativity uEntry into research at an early age through a flexible borderless curriculum and research projects Annual Report 2016-17 Correct Citation IISER Pune Annual Report 2016-17, Pune, India Published by Dr. K.N. Ganesh Director Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Pune Dr. Homi J. Bhabha Road Pashan, Pune 411 008, India Telephone: +91 20 2590 8001 Fax: +91 20 2025 1566 Website: www.iiserpune.ac.in Compiled and Edited by Dr. Shanti Kalipatnapu Dr. V.S. Rao Ms. Kranthi Thiyyagura Photo Courtesy IISER Pune Students and Staff © No part of this publication be reproduced without permission from the Director, IISER Pune at the above address Printed by United Multicolour Printers Pvt. -

We Had Vide HO Circular 443/2015 Dated 07.09.2015 Communicated

1 CIRCULAR NO.: 513/2015 HUMAN RESOURCES WING I N D E X : STF : 23 INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS SECTION HEAD OFFICE : BANGALORE-560 002 D A T E : 21.10.2015 A H O N SUB: IBA MEDICAL INSURANCE SCHEME FOR RETIRED OFFICERS/ EMPLOYEES. ******* We had vide HO Circular 443/2015 dated 07.09.2015 communicated the salient features of IBA Medical Insurance Scheme for the Retired Officers/ Employees and called for the option from the eligible retirees. Further, the last date for submission of options was extended upto 20.10.2015 vide HO Circular 471/2015 dated 01.10.2015. The option received from the eligible retired employees with mode of exit as Superannuation, VRS, SVRS, at various HRM Sections of Circles have been consolidated and published in the Annexure. We request the eligible retired officers/ employees to check for their name if they have submitted the option in the list appended. In case their name is missing we request such retirees to take up with us by 26.10.2015 by sending a scan copy of such application to the following email ID : [email protected] Further, they can contact us on 080 22116923 for further information. We also observe that many retirees have not provided their email, mobile number. In this regard we request that since, the Insurance Company may require the contact details for future communication with the retirees, the said details have to be provided. In case the retirees are not having personal mobile number or email ID, they have to at least provide the mobile number or email IDs of their near relatives through whom they can receive the message/ communication. -

Report Title Raabe, Wilhelm Karl = Corvinus, Jakob (Pseud.)

Report Title - p. 1 of 672 Report Title Raabe, Wilhelm Karl = Corvinus, Jakob (Pseud.) (Eschershausen 1831-1910 Braunschweig) : Schriftsteller Biographie 1870 Raabe, Wilhelm Karl. Der Schüdderump [ID D15996]. Ingrid Schuster : Raabe verwendet im Roman den chinesischen Gartenpavillon als bezugsreiches Symbol für die zwei Hauptpersonen, der Ritter von Glaubigernd und das Fräulein von St. Trouin, sowie Chinoiserien in Adelaide von St. Trouins Zimmer. [Schu4:S. 162-168] Bibliographie : Autor 1870 Raabe, Wilhelm Karl. Der Schüdderump. In : Westermann's Jahrbuch der Illustrirten deutschen Monatshefte ; Bd. 27, N.F. Bd. 11, Oct.1869-März 1870. [Schu4] 1985 [Raabe, Wilhelm]. Que xiang chun qiu. Wang Kecheng yi. (Shanghai : Yi wen chu ban she, 1985). Übersetzung von Raabe, Wilhelm. Die Chronik der Sperlingsgasse. Hrsg. von Jakob Corvinus. (Berlin : Stage, 1857). [ZhaYi2,WC] 1997 [Raabe, Wilhelm Karl]. Hun xi yue shan. Weilian Labei zhu ; Wang Kecheng yi. (Shanghai : Shanghai yi wen chu ban she, 1997). Übersetzung von Raabe, Wilhelm Karl. Abu Telfan : oder, Die Heimkehr vom Mondgebirge : Roman. (Köln : Atlas-Verlag, 1867). [WC] Raaschou, Peter Theodor (Dänemark 1862-1924 Shanghai) : Diplomat Biographie 1907-1908 Peter Theodor Raaschou ist Konsul des dänischen Konsulats in Shanghai. [Who2] 1909-1917 Peter Theodor Raaschou ist Generalkonsul des dänischen Konsulats in Shanghai. 1917 ist er Senior Konsul. [Who2] Raasloff, Waldemar Rudolf (1815-1883) : Dänischer Politiker, General Biographie 1863 Dritte dänische diplomatische Mission nach China durch Waldemar Rudolf Raasloff. [BroK1] Rabban Bar Sauma (ca. 1220-1294) : Türkisch-mongolischer Mönch, Nestorianer Bibliographie : erwähnt in 1992 Rossabi, Morris. Voyager from Xanadu : Rabban Sauma and the first journey from China to the West. (Tokyo ; New York, N.Y. -

The Chinese People's Liberation Army at 75

THE LESSONS OF HISTORY: THE CHINESE PEOPLE’S LIBERATION ARMY AT 75 Edited by Laurie Burkitt Andrew Scobell Larry M. Wortzel July 2003 ***** The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This report is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. ***** Comments pertaining to this report are invited and should be forwarded to: Director, Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 122 Forbes Ave., Carlisle, PA 17013-5244. Copies of this report may be obtained from the Publications Office by calling (717) 245-4133, FAX (717) 245-3820, or via the Internet at [email protected] ***** Most 1993, 1994, and all later Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) monographs are available on the SSI Homepage for electronic dissemination. SSI’s Homepage address is: http:// www.carlisle.army.mil/ssi/index.html ***** The Strategic Studies Institute publishes a monthly e-mail news- letter to update the national security community on the research of our analysts, recent and forthcoming publications, and upcoming conferences sponsored by the Institute. Each newsletter also pro- vides a strategic commentary by one of our research analysts. If you are interested in receiving this newsletter, please let us know by e-mail at [email protected] or by calling (717) 245-3133. ISBN 1-58487-126-1 ii CONTENTS Foreword Ambassador James R. Lilley . v Part I: Overview. 1 1. Introduction: The Lesson Learned by China’s Soldiers Laurie Burkitt, Andrew Scobell, and Larry M. -

NASA's International Relations in Space

Notes 1 Introduction and Historical Overview: NASA’s International Relations in Space 1. James R. Hansen, First Man. The Life of Neil A. Armstrong (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2005), 493. 2. Ibid., 393, 503. 3. Ibid., 505. 4. For survey of the historical literature, see Roger D. Launius, “Interpreting the Moon Landings: Project Apollo and the Historians,” History and Technology 22:3 (September 2006), 225–255. On the gendering of the Apollo program, see Margaret A. Weitekamp, The Right Stuff, the Wrong Sex: The Lovelace Women in the Space Program (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004); “The ‘Astronautrix’ and the ‘Magnificent Male.’ Jerrie Cobb’s Quest to be the First Woman in America’s Manned Space pro- gram,” in Avital H. Bloch and Lauri Umansky (eds.), Impossible to Hold. Women and Culture in the 1960s (New York: New York University Press), 9–28. 5. Hansen, First Man , 513–514. 6. Sunny Tsiao, “Read You Loud and Clear.” The Story of NASA’s Spaceflight Tracking and Data Network (Washington, DC: NASA SP-2007–4232), Chapter 5 . 7. Experiment Operations during Apollo EVAs. Experiment: Solar Wind Experiment, http://ares.jsc.nasa.gov/humanexplore/exploration/exlibrary/docs/apollocat/ part1/swc.htm (accessed August 31, 2008). 8. Thomas A. Sullivan, Catalog of Apollo Experiment Operations (Washington, DC: NASA Reference Publication 1317, 1994), 113–116. Geiss’s team also measured the amounts of rare gases trapped in lunar rocks: P. Eberhart and J. Geiss, et al., “Trapped Solar Wind Noble Gases, Exposure Age and K/Ar Age in Apollo 11 Lunar Fine Material,” in A. -

Who's Behind China's High-Technology “Revolution”?

Who’s Behind China’s Evan A. Feigenbaum High-Technology “Revolution”? How Bomb Makers Remade Beijing’s Priorities, Policies, and Institutions For seven years after the Tiananmen Square tragedy of 1989, virtually all signiªcant issues in U.S.- China relations became subordinate to concern about human rights and China’s suppression of political dissent. Yet in the three years since China’s 1996 missile exercise in the Taiwan Strait, high-technology issues have come increasingly to replace human rights at the center of the contentious and often politicized discussion that characterizes current debate about U.S.-China policy. Recent allegations concerning satellite exports and nuclear espionage, in particular, demonstrate the centrality of high technology to the debate about China’s place in the world. This makes it especially important to explore links that may bind China’s national technology and industrial policies to its ap- proach to security and development. How has the Chinese understanding of this linkage changed as the past priority of militarized growth has given way to the rapid expansion of a commercial economy since the late 1970s?1 Who is responsible for making important technology decisions in China? How have Chinese technology leaders thought about the relationship between technology and national power during the past twenty years? Has political change affected this worldview? Finally, how has renewed contact with international technical circles since the 1970s affected the Chinese approach to national high-tech strategy and investment? Evan A. Feigenbaum is a Fellow at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University’s John F. -

The Accordion in Twentieth-Century China A

AN UNTOLD STORY: THE ACCORDION IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY CHINA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN MUSIC AUGUST 2004 By Yin YeeKwan Thesis Committee: Frederick Lau, Chairperson Ricardo D. Trimillos Fred Blake ©Copyright2004 by YinYeeKwan iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My 2002 and 2003 fieldwork in the People's Republic ofChina was funded by The Arts and Sciences Grant from the University ofHawai'i at Manoa (UHM). I am grateful for the generous support. I am also greatly indebted to the accordionists and others I interviewed during this past year in Hong Kong, China, Phoenix City, and Hawai'i: Christie Adams, Chau Puyin, Carmel Lee Kama, 1 Lee Chee Wah, Li Cong, Ren Shirong, Sito Chaohan, Shi Zhenming, Tian Liantao, Wang Biyun, Wang Shusheng, Wang Xiaoping, Yang Wentao, Zhang Gaoping, and Zhang Ziqiang. Their help made it possible to finish this thesis. The directors ofthe accordion factories in China, Wang Tongfang and Wu Rende, also provided significant help. Writing a thesis is not the work ofonly one person. Without the help offriends during the past years, I could not have obtained those materials that were invaluable for writings ofthis thesis. I would like to acknowledge their help here: Chen Linqun, Chen Yingshi, Cheng Wai Tao, Luo Minghui, Wong Chi Chiu, Wang Jianxin, Yang Minkang, and Zhang Zhentao. Two others, Lee Chinghuei and Kaoru provided me with accordion materials from Japan. I am grateful for the guidance and advice ofmy committee members: Professors Frederick Lau, Ricardo D. -

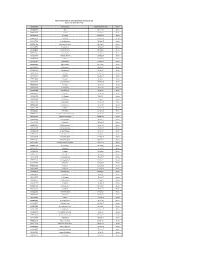

Agent Code Agent Name Commencement Date Status ABH1102649

Advisor On-Boarded List Aditya Birla Health Insurance Co Ltd. (Dated 30th November 2017) Agent Code Agent Name Commencement Date Status ABH1102649 . Devi 22-Jun-17 Active ABH1108288 . Kamna 21-Sep-17 Active ABH1110946 A A Date 10-Nov-17 Active ABH1100733 A Abishek 10-Dec-16 Active ABH1107599 A Adaikkammai 09-Sep-17 Active ABH1107385 A Alexander Nelson 06-Sep-17 Active ABH1108755 A Amrudeen 28-Sep-17 Active ABH1108024 A Anishfathima 18-Sep-17 Active ABH1104587 A Antony Rai 28-Jul-17 Active ABH1107372 A Antony Selvaraj 06-Sep-17 Active ABH1111676 A Balaji 22-Nov-17 Active ABH1105915 A Balaraman 16-Aug-17 Active ABH1101412 A Banukumar 15-Feb-17 Active ABH1109210 A Banupriya 06-Oct-17 Active ABH1113471 A Damayanthi 30-Dec-17 Active ABH1112656 A Devi 15-Dec-17 Active ABH1101841 A Gayathri 07-Apr-17 Active ABH1110059 A Gayatri 24-Oct-17 Active ABH1107235 A Govindarajan 04-Sep-17 Active ABH1103600 A Grover 14-Jul-17 Active ABH1104672 A Janardhan 29-Jul-17 Active ABH1101898 A Jayakeerthi 15-Apr-17 Active ABH1100835 A Justina 21-Dec-16 Active ABH1104360 A K Bhargav 26-Jul-17 Active ABH1109964 A K Muthaiah 21-Oct-17 Active ABH1113305 A Kalaivanan 27-Dec-17 Active ABH1104499 A Kemburai 27-Jul-17 Active ABH1111295 A Khizar 15-Nov-17 Active ABH1100265 A Kiirthana 16-Nov-16 Active ABH1108423 A Lakshmi Samba Sivaprasad 23-Sep-17 Active ABH1113157 A Marutha Nayagam 26-Dec-17 Active ABH1106763 A N Venugopal 28-Aug-17 Active ABH1101338 A Nandhini 09-Feb-17 Active ABH1101147 A Narayanamma 19-Jan-17 Active ABH1101647 A P Jayachandran 15-Mar-17 Active ABH1103278 -

Brief Biographical Sketch of Pramod Kale –

Brief biographical sketch of Pramod Kale – Pramod Kale, born on 4th March in 1941 at Pune, was student of Fergusson College in 1956-1958. Later he went to M. S. University, Vadodara for his B. Sc. Physics degree which he obtained in 1960. He obtained his M. Sc. Physics (Electronics) degree in 1962 from Gujarat University, Ahmedabad. Pramod Kale had worked with the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) for over thirty-two years (1962-1994) during which he held various leadership positions. He started his work on satellite tracking at the Physical Research Laboratory - PRL, Ahmedabad in 1960 and was a member of the first team sent to Goddard Space Flight Center, NASA, USA for training in launching sounding rockets in 1963 and establishing the Thumba Equatorial Rocket Launching Station – TERLS. The first rocket flight took place in 1963 from TERLS on 21st November 1963. He had worked as a Research Student with Dr. Vikram Sarabhai at PRL, Ahmedabad for three years 1962 – 1965. Some of his notable assignments and positions in ISRO / DOS were – Head, Electronics Division (Satellite Systems), Space Science and Technology Center, Thiruvananthapuram. Project Manager, (Electronics and TV Hardware); Satellite Instructional Television Experiment (SITE), SAC, Ahmedabad Project Director; INSAT 1 Space Segment Project, Bangalore Mission Director, ISRO Payload Scientist Mission Director; Space Applications Center (SAC), Ahmedabad Director; Vikram Sarabhai Space Center (VSSC), Thiruvananthapuram He had been active in teaching at the Gujarat University for the Post Graduate Diploma course in Space Science and Applications. He is continuing to give lectures on Space Communications Systems for the students at CSSTEAP program at the Space Applications Center.