THE EAST-WEST CENTER-Formally Known As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethnic Studies Program Facing Potential Budget Cuts

THE UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO © THURSDAY, MARCH 10, 2016 • VOL. 113, ISSUE 16 NEWS SCENE OPINION SPORTS AC BSU anticipates the Are you watching AO Professor Evelyn I. Mens and womens University's official 06 Samantha Bee's new Rodriguez advocates 10 basketball travel to Las response to their list of late-night show? You for the large-scale Vegas, Nevada for the demands published in totally should be, preservation of Ethnic WCC Tournament. Dec. according to junior Studies. David Garcia. Students part ofthe Asian and Pacific Islanders in US Societies class show their support. COURTESY OF COLLEEN BARRETT USF SUPPORTS SFSU ETHNIC STUDIES PROGRAM FACING POTENTIAL BUDGET CUTS BRIAN HEALY university was mulling over a proposal to cut to address the budget cut threats with SF- StaffWriter the department's funding, which SFSU ad SU's President, Leslie Wong, Latino/a Stud ministration later confirmed. ies major Oscar Pena directed his attention There are currently 61 undergraduate The main reason university administra to the administration and said, "Shame on Ethnic Studies programs across universities tion is discussing budget cuts is because they you guys for putting us in this situation," be in the United States. Many offer the study of allege that the College of Ethnic Studies fore elaborating on how crucial the college race, ethnicity, nation, and identity under a overspends and misallocar.es the funds pro has been in shaping his life. different academic heading, but all of them, vided to them. Faculty and staff of the College of Eth including USF, built their programs using However, SF Gate reports that the school nic Studies also came out in force, defend the groundwork laid by nearby San Fran gave the Ethnic Studies program $3.6 mil ing theit use of funds and asserting that the cisco State University. -

Birth of Bangladesh: Down Memory Lane

Indian Foreign Affairs Journal Vol. 4, No. 3, July - September, 2009, 102-117 ORAL HISTORY Birth of Bangladesh: Down Memory Lane Arundhati Ghose, often acclaimed for espousing wittily India’s nuclear non- proliferation policy, narrates the events associated with an assignment during her early diplomatic career that culminated in the birth of a nation – Bangladesh. Indian Foreign Affairs Journal (IFAJ): Thank you, Ambassador, for agreeing to share your involvement and experiences on such an important event of world history. How do you view the entire episode, which is almost four decades old now? Arundhati Ghose (AG): It was a long time ago, and my memory of that time is a patchwork of incidents and impressions. In my recollection, it was like a wave. There was a lot of popular support in India for Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his fight for the rights of the Bengalis of East Pakistan, fund-raising and so on. It was also a difficult period. The territory of what is now Bangladesh, was undergoing a kind of partition for the third time: the partition of Bengal in 1905, the partition of British India into India and Pakistan and now the partition of Pakistan. Though there are some writings on the last event, I feel that not enough research has been done in India on that. IFAJ: From India’s point of view, would you attribute the successful outcome of this event mainly to the military campaign or to diplomacy, or to the insights of the political leadership? AG: I would say it was all of these. -

Sensitivity Testing Current Migration Patterns to Climate Change and Variability in Bangladesh

Sensitivity testing current migration patterns to climate change and variability in Bangladesh Dominic Kniveton, Maxmillan Martin and Pedram Rowhani Working paper 5 An output of research on climate change related migration in Bangladesh, conducted by Refugee and Migratory Movements Research Unit (RMMRU), University of Dhaka, and Sussex Centre for Migration Research (SCMR), University of Sussex, with support from Climate & Development Knowledge Network (CDKN) Copyright: RMMRU and SCMR, 2013 Refugee and Migratory Movements Research Unit Sattar Bhaban (4th Floor) 3/3-E, Bijoynagar, Dhaka-1000, Bangladesh. Tel: +880-2-9360338, Fax: +880-2-8362441 E-mail: [email protected], Web: www.rmmru.org | www.samren.net Sussex Centre for Migration Research School of Global Studies University of Sussex Falmer, Brighton BN1 9SJ, UK Tel: +44 1273 873394, Fax : +44 1273 620662 Email: [email protected], Web: www.sussex.ac.uk/migration About the authors: Dominic Kniveton is Professor of Climate Science and Society at the Department of Geography, School of Global Studies, University of Sussex, UK, Email: [email protected] Maxmillan Martin is a PhD student at the Department of Geography, School of Global Studies, University of Sussex, UK Pedram Rowhani is Lecturer in Geography at the Department of Geography, School of Global Studies, University of Sussex, UK Sensitivity testing current migration patterns to climate change and variability in Bangladesh Introduction It is widely recognised that the decision to migrate is multi-causal and context specific. According to the Foresight conception of migration and environmental change migration can be seen as being driven or de- termined by the multi-scale influences of social, economic, demographic, environmental and political fac- tors such as kinship links, job opportunities, population growth, loss of land and conflict, to give just a few examples; while the ability to migrate is controlled by household and individual access to resources, family obligations and migration networks (Foresight 2012). -

IPP: Bangladesh: Second Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project

Second Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project (RRP BAN 42248) Indigenous Peoples Plan March 2011 BAN: Second Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project Prepared by ANZDEC Ltd for the Ministry of Chittagong Hill Tracts Affairs and Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 16 March 2011) Currency unit – taka (Tk) Tk1.00 = $0.0140 $1.00 = Tk71.56 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank ADR – alternative dispute resolution AP – affected person CHT – Chittagong Hill Tracts CHTDF – Chittagong Hill Tracts Development Facility CHTRC – Chittagong Hill Tracts Regional Council CHTRDP – Chittagong Hill Tracts Rural Development Project CI – community infrastructure DC – deputy commissioner DPMO – district project management office GOB – Government of Bangladesh GPS – global positioning system GRC – grievance redress committee HDC – hill district council INGO – implementing NGO IP – indigenous people IPP – indigenous peoples plan LARF – land acquisition and resettlement framework LCS – labor contracting society LGED – Local Government Engineering Department MAD – micro agribusiness development MIS – management information system MOCHTA – Ministry of Chittagong Hill Tracts Affairs NOTE (i) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This indigenous peoples plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. 1 CONTENTS Page A. Executive Summary 3 B. -

Challenges of Islamic Da'wah in Bangladesh: the Christian

IIUC STUDIES ISSN 1813-7733 Vol. – 4, December 2007 Published in April 2008 (p 87-108) Challenges of Islamic Da‘wah in Bangladesh: The Christian Missions and Their Evangelization Dr. Md. Yousuf Ali∗ Abu Sadat Nurullah∗∗ Abstract: Although Bangladesh is the second largest Muslim populated country in the world, there are several challenges of Islamic da‘wah here. The Christian mission, taking the opportunity of people’s poverty and distress, is evangelizing them through financial assistance and other means. The rapidly increasing number of conversion to Christianity among the tribal population is alarming. The missionary activities are spreading around the country, chiefly in the intellectual arena, in educational institutions, and in other aspects of life. The influence of it on the culture, education, religion and lifestyle of people results into converting people to the Christian ideology. Particularly the young generations are inclining towards this lucrative dogma of the new age. Media, both print and electronic, are propagating and claiming the banning of the da‘wah movement. In these situation, the Islamic da‘wah movements require to explore and implement new methodology to face the enormous challenges to prevent Bangladesh from becoming a Christian country in future. Keywords: Islamic da‘wah, Christian mission, and evangelization. Introduction: Bangladesh has the fourth largest concentration of Muslim populations in the world with a population of about 140 billion, of which 88 percent are Muslims. However, majority of the population (74 percent according to 2001 census) reside in rural area with lower economic condition and lowest standards of living. In fact, about half of the ∗ Assistant Professor, Faculty of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences, IIUM, Malaysia ∗∗ Student Department of Sociology and Anthropology, International Islamic University Malaysia IIUC Studies, Vol. -

MIRPUR PAPERS, Volume 22, Issue 23, November 2016

ISSN: 1023-6325 MIRPUR PAPERS, Volume 22, Issue 23, November 2016 MIRPUR PAPERS Defence Services Command and Staff College Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka-1216 Bangladesh MIRPUR PAPERS Chief Patron Major General Md Saiful Abedin, BSP, ndc, psc Editorial Board Editor : Group Captain Md Asadul Karim, psc, GD(P) Associate Editors : Wing Commander M Neyamul Kabir, psc, GD(N) (Now Group Captain) : Commander Mahmudul Haque Majumder, (L), psc, BN : Lieutenant Colonel Sohel Hasan, SGP, psc Assistant Editor : Major Gazi Shamsher Ali, AEC Correspondence: The Editor Mirpur Papers Defence Services Command and Staff College Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka – 1216, Bangladesh Telephone: 88-02-8031111 Fax: 88-02-9011450 E-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2006 DSCSC ISSN 1023 – 6325 Published by: Defence Services Command and Staff College Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka – 1216, Bangladesh Printed by: Army Printing Press 168 Zia Colony Dhaka Cantonment, Dhaka-1206, Bangladesh i Message from the Chief Patron I feel extremely honoured to see the publication of ‘Mirpur Papers’ of Issue Number 23, Volume-I of Defence Services Command & Staff College, Mirpur. ‘Mirpur Papers’ bears the testimony of the intellectual outfit of the student officers of Armed Forces of different countries around the globe who all undergo the staff course in this prestigious institution. Besides the student officers, faculty members also share their knowledge and experience on national and international military activities through their writings in ‘Mirpur Papers’. DSCSC, Mirpur is the premium military institution which is designed to develop the professional knowledge and understanding of selected officers of the Armed Forces in order to prepare them for the assumption of increasing responsibility both on staff and command appointment. -

India-Bangladesh Border Haats BRIEFING PAPER #1/2020 Unnayan Shamannay

India-Bangladesh Border Haats BRIEFING PAPER #1/2020 Unnayan Shamannay Role of Border Haat in Management of India-Bangladesh Border Joyeeta Bhattacharjee* The border haats have been transformational in the management of India and Bangladesh border. Traditionally, border management was perceived, from the prism of security, therefore, restrictions were imposed on the people in the bordering areas, thus hampering development. Given the security-centric approach to the border, India undertook a policy of restraining development in the areas adjacent to the international boundary. Unfortunately, such a policy backfired and instead of securing the border, increased vulnerabilities and the border region became a hub of illegal activities. The haats were established to bolster development in the border region by generating livelihood opportunities and controlling cross-border illegal activities. This Briefing Paper studies the role and impact of the border haats in the management of the India- Bangladesh border. Understanding Border The border management policies are determined by Management the nature of bilateral relationship a country enjoys with the other country across the border. Despite Border management has two major objectives – divergent approaches, security is a key component of firstly, to facilitate the movement of legitimate goods border management across the globe. For example, and people across the border between two India shares around 15,000 kilometres of land sovereign countries; and secondly, to ensure the borders with six countries, however, its policies are security of the country by restricting entry of illegal not uniform. The country follows different policies goods and those individuals across the border who based on the nature of the relationship with a specific 1 might disturb the peace. -

Bangladesh: Back to the Future

BANGLADESH: BACK TO THE FUTURE Asia Report N°226 – 13 June 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. THE LEGACY OF THE CARETAKER GOVERNMENT ......................................... 2 III. SHATTERED HOPES UNDER THE AWAMI LEAGUE .......................................... 4 A. THE FIFTEENTH AMENDMENT ...................................................................................................... 4 B. CRACKDOWN ON THE OPPOSITION ............................................................................................... 5 C. POLITICISATION OF THE SECURITY FORCES AND JUDICIARY ........................................................ 6 D. WAR CRIMES TRIALS ................................................................................................................... 7 E. CORRUPTION ................................................................................................................................ 8 F. THE AWAMI LEAGUE IN POWER ................................................................................................... 8 IV. THE OTHER PARTIES ................................................................................................... 9 A. THE BNP .................................................................................................................................... -

Bangladesh Legislative Elections, 29 December 2008

LEGISLATIVE ELECTIONS IN BANGLADESH ELECTION OBSERVATION DELEGATION 27 – 31 December 2008 REPORT BY MR Charles TANNOCK CHAIRMAN OF THE DELEGATION Report 2 Annexes 7 1 INTRODUCTION Following an invitation from the Bangladeshi authorities, the Conference of Presidents decided at its meeting on 23 October to authorise the sending of a delegation of the European Parliament to observe the legislative elections in Bangladesh, at that time scheduled for the 18 December. The Constitutive Meeting of the EP EOM was held in Strasbourg on the 19th November and M. Robert Evans (PSE,UK) was elected Chairman. However, the rescheduling of the Election date in Bangladesh to the 29th December made it, unfortunately, not possible for many of the Members initially appointed by their Political Groups to maintain their availability. A new constitutive meeting was therefore held on the 10th December, with M. Charles Tannock (EPP/ED, UK) elected Chairman of a 4-strong delegation; as is customary, these Members were appointed by the political groups in accordance with the rolling d'Hondt system (the list of participants is annexed to this report; the ALDE political group gave its seat to the N/I group). Taking into account this change of dates, the Conference of Presidents re-examined the situation at its meeting of the 17th December and confirmed its initial decision to send a parliamentary delegation. As is usual, the European Parliament's delegation was fully integrated into the European Union Election Observation Mission (EU EOM), which was led by Mr Alexander Graf LAMBSDORFF, MEP (ALDE, D). The EU EOM deployed 150 observers from 25 EU Member States plus Norway and Switzerland. -

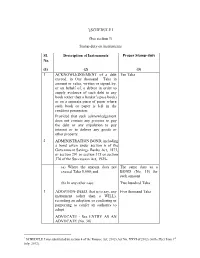

[SCHEDULE I (See Section 3) Stamp Duty on Instruments Sl. No. Description of Instruments Proper Stamp-Duty (1) (2) (3) 1 ACKNOWL

1[SCHEDULE I (See section 3) Stamp duty on instruments Sl. Description of Instruments Proper Stamp-duty No. (1) (2) (3) 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT of a debt Ten Taka exceed, in One thousand Taka in amount or value, written or signed by, or on behalf of, a debtor in order to supply evidence of such debt in any book (other than a banker’s pass book) or on a separate piece of paper where such book or paper is left in the creditors possession: Provided that such acknowledgement does not contain any promise to pay the debt or any stipulation to pay interest or to deliver any goods or other property. 2 ADMINISTRATION BOND, including a bond given under section 6 of the Government Savings Banks Act, 1873, or section 291 or section 375 or section 376 of the Succession Act, 1925- (a) Where the amount does not The same duty as a exceed Taka 5,000; and BOND (No. 15) for such amount (b) In any other case. Two hundred Taka 3 ADOPTION-DEED, that is to say, any Five thousand Taka instrument (other than a WILL), recording an adoption, or conferring or purporting to confer an authority to adopt. ADVOCATE - See ENTRY AS AN ADVOCATE (No. 30) 1 SCHEDULE I was substituted by section 4 of the Finance Act, 2012 (Act No. XXVI of 2012) (with effect from 1st July, 2012). 4 AFFIDAVIT, including an affirmation Two hundred Taka or declaration in the case of persons by law allowed to affirm or declare instead of swearing. EXEMPTIONS Affidavit or declaration in writing when made- (a) As a condition of enlistment under the Army Act, 1952; (b) For the immediate purpose of being field or used in any court or before the officer of any court; or (c) For the sole purpose of enabling any person to receive any pension or charitable allowance. -

In East Pakistan (1947-71)

Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh (Hum.), Vol. 63(1), 2018, pp. 59-89 THE INVISIBLE REFUGEES: MUSLIM ‘RETURNEES’ IN EAST PAKISTAN (1947-71) Anindita Ghoshal* Abstract Partition of India displaced huge population in newly created two states who sought refuge in the state where their co - religionists were in a majority. Although much has been written about the Hindu refugees to India, very less is known about the Muslim refugees to Pakistan. This article is about the Muslim ‘returnees’ and their struggle to settle in East Pakistan, the hazards and discriminations they faced and policy of the new state of Pakistan in accommodating them. It shows how the dream of homecoming turned into disillusionment for them. By incorporating diverse source materials, this article investigates how, despite belonging to the same religion, the returnee refugees had confronted issues of differences on the basis of language, culture and region in a country, which was established on the basis of one Islamic identity. It discusses the process in which from a space that displaced huge Hindu population soon emerged as a ‘gradual refugee absorbent space’. It studies new policies for the rehabilitation of the refugees, regulations and laws that were passed, the emergence of the concept of enemy property and the grabbing spree of property left behind by Hindu migrants. Lastly, it discusses the politics over the so- called Muhajirs and their final fate, which has not been settled even after seventy years of Partition. This article intends to argue that the identity of the refugees was thus ‘multi-layered’ even in case of the Muslim returnees, and interrogates the general perception of refugees as a ‘monolithic community’ in South Asia. -

Tender Specification of 01Xlong Range Air Defence

SECRET ANNEX A TENDER NO: 06.06.0000.275.07.229.19 DATED: 11 FEBRUARY 2020 TENDER SPECIFICATION FOR PROCUREMENT OF 04 X AUTOMATED WAREHOUSE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM (AWMS) FOR 201 MAINTENANCE UNIT, BANGLADESH AIR FORCE (201MU BAF) PART 1: GENERAL INFORMATION AND BIDDER’S RESPONSIBILITIES Introduction 01. Bangladesh Air Force (BAF) has planned to procure 04X Automated Warehouse Management System in the financial year 2019-2020. The AWMS will be installed at existing Warehouse of 201 MU BAF site at Dhaka Cantonment. The AWMS shall have the ability to receive and issue all types of items automatically for better inventory management. The offered AWMS should satisfactorily operate in the climatic conditions of Bangladesh. The AWMS system shall allow accommodating all types of aircraft and radar spares which size and shapes are within limit of try of AWMS. 02. For better understanding and to evaluate, all the prospective bidders on the same platform, the tender specification has been divided into three parts: a. Part-1: General Information and Bidder’s Responsibilities. b. Part-2: Technical Specification (Essential and Optional Requirement). c. Part-3: General Terms and Conditions. 03. In Part-2, there are essential criteria and optional items. Bidders failing to comply with essential criteria will be disqualified. However, Bidder has to quote price of all the optional items, but BAF may take some or all optional items as per the requirement. Price of optional features/items will not be considered for determining financial competitiveness. 04. Prospective bidders are to comply with the requirements and terms and conditions of the tender specification mentioned in Part-1, Part-2 and Part-3 of the tender specification.