Review of Phoenix from the Ashes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pastors and the Ecclesial Movements

Laity Today A series of studies edited by the Pontifical Council for the Laity PONTIFICIUM CONSILIUM PRO LAICIS Pastors and the ecclesial movements A seminar for bishops “ I ask you to approach movements with a great deal of love ” Rocca di Papa, 15-17 May 2008 LIBRERIA EDITRICE VATICANA 2009 © Copyright 2009 - Libreria Editrice Vaticana 00120 VATICAN CITY Tel. 06.698.85003 - Fax 06.698.84716 ISBN 978-88-209-8296-6 www.libreriaeditricevaticana.com CONTENTS Foreword, Cardinal Stanisław Ryłko ................ 7 Address of His Holiness Benedict XVI to the participants at the Seminar ............................. 15 I. Lectures Something new that has yet to be sufficiently understood . 19 Ecclesial movements and new communities in the teaching of John Paul II and Benedict XVI, Cardinal Stanisław Ryłko . 21 Ecclesial movements and new communities in the mission of the Church: a theological, pastoral and missionary perspective, Msgr. Piero Coda ........................ 35 Movements and new communities in the local Church, Rev. Arturo Cattaneo ...................... 51 Ecclesial movements and the Petrine Ministry: “ I ask you to col- laborate even more, very much more, in the Pope’s universal apostolic ministry ” (Benedict XVI), Most Rev. Josef Clemens . 75 II. Reflections and testimonies II.I. The pastors’ duty towards the movements . 101 Discernment of charisms: some useful principles, Most Rev. Alberto Taveira Corrêa . 103 Welcoming movements and new communities at the local level, Most Rev. Dominique Rey . 109 5 Contents Pastoral accompaniment of movements and new communities, Most Rev. Javier Augusto Del Río Alba . 127 II.2. The task of movements and new communities . 133 Schools of faith and Christian life, Luis Fernando Figari . -

The Holy See

The Holy See LETTER OF JOHN PAUL II TO THE CARDINAL VICAR OF THE DIOCESE OF ROME, CARDINAL CAMILLO RUINI Venerable Brother! On Sunday, 16 December, God willing, I will visit the Roman parish of St María Josefa of the Heart of Jesus. With this visit I will have visited 300 parishes since I began this spiritual pastoral pilgrimage in 1978 with the visit to the parish of St Francis Xavier in the Garbatella area. Spontaneously I feel the desire to give thanks to God as I reach this significant goal. It is a sentiment that I want to share with you, my Cardinal Vicar for the Diocese of Rome, while with great fondness, I recall your esteemed predecessor, the late Cardinal Ugo Poletti, who accompanied me in the first part of this pilgrimage, and with tact and care helped me to learn the Diocese. I am most grateful, because for me the visit to the Roman parishes has always been an enjoyable task. To pass the morning and afternoon among the faithful, in the various neighborhoods, with the parish priest and the priests, religious, and dedicated laity; celebrating the Mass in the parish church; greeting the children, the young people, the pastoral councils; reawakening in each the commitment to the new evangelization, all this has been and still is of great importance as I continue to become familiar with the human, social and spiritual reality of the Diocese. So much more for a Pope who has "come from a far country". If today I can say that I feel fully "Roman" it is thanks to the visits to the parishes of this extraordinary and beautiful City. -

Fr. Luigi Villa: Probably John XXIII and Paul VI Initiated in the Freemasonry?

PAUL VI… BEATIFIED? By father Doctor LUIGI VILLA PAUL VI… BEATIFIED? By father Doctor LUIGI VILLA (First Edition: February 1998 – in italian) (Second Edition: July 2001 –in italian) EDITRICE CIVILTà Via Galileo Galilei, 121 25123 BRESCIA (ITALY) PREFACE Paul VI was always an enigma to all, as Pope John XXIII did himself observe. But today, after his death, I believe that can no longer be said. In the light, in fact, of his numerous writings and speeches and of his actions, the figure of Paul VI is clear of any ambiguity. Even if corroborating it is not so easy or simple, he having been a very complex figure, both when speaking of his preferences, by way of suggestions and insinuations, and for his abrupt leaps from idea to idea, and when opting for Tradition, but then presently for novelty, and all in language often very inaccurate. It will suffice to read, for example, his Addresses of the General Audiences, to see a Paul VI prey of an irreducible duality of thought, a permanent conflict between his thought and that of the Church, which he was nonetheless to represent. Since his time at Milan, not a few called him already “ ‘the man of the utopias,’ an Archbishop in pursuit of illusions, generous dreams, yes, yet unreal!”… Which brings to mind what Pius X said of the Chiefs of the Sillon1: “… The exaltation of their sentiments, the blind goodness of their hearts, their philosophical mysticisms, mixed … with Illuminism, have carried them toward another Gospel, in which they thought they saw the true Gospel of our Savior…”2. -

Towards a Deepened Understanding of the Liturgical Value of the Motu Proprio of 2 July 1988

Pontifical University of Saint Thomas in Rome Faculty of Theology ECCLESIA DEI ADFLICTA Towards a Deepened Understanding of the Liturgical Value of the Motu Proprio of 2 July 1988 Tesina submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a License in Sacred Theology with a specialization in Spiritual Theology Moderated by The Reverend Joseph C. Henchey, C.S.S. The Reverend Daniel Ward Oppenheimer Fraternitas Sacerdotalis Sancti Petri Casa Santa Maria January 22, 1999 Rome 2 The only way to make Vatican II credible is to present it clearly as what it is: part of the whole single Tradition of the Church and its faith.1 1 Joseph Ratzinger, “Speech to the Bishops of Chile”, 11, delivered 13 July 1988 in the aftermath of the 30 June 1988 schism; in Canonical Proposal of the Priestly Fraternity of Saint Peter (Scranton: Privately published, 14 September 1993), 61-64. [Cf. Appendix] 3 Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION . 4 II. BACKGROUND TO THE QUESTION . 7 A. Principles from the Council . 7 B. The Nature of Liturgy . 15 C. After the Council . 36 III. THE MOTU PROPRIO ECCLESIA DEI ADFLICTA 76 A. 1988 Schism of Archbishop Lefebvre . 76 B. Pope John Paul II’s Pastoral Measure . 81 C. Lasting Effects of the Motu Proprio . 92 IV. CONCLUSION . 95 APPENDICES: Letter from the CDW: Quattuor Abhinc Annos . 96 John Paul II: Motu Proprio Ecclesia Dei Adflicta . 97 Cardinal Ratzinger: “Speech to the Bishops of Chile” 100 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 104 4 I. INTRODUCTION It is the intention of this paper to examine some of the central causes and circumstances operative in the schism of June 30, 1988, which derived in considerable measure from the complexity of changes that occurred in the liturgy of the Roman Rite. -

The-Problem-With-Vatican-II.Pdf

THE PROBLEM WITH VATICAN II Michael Baker © Copyright Michael Baker 2019 All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act (C’th) 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher at P O Box 1282, Goulburn NSW 2580. Published by M J Baker in Goulburn, New South Wales, December 2019. This version revised, and shortened, January 2021. Digital conversion by Mark Smith 2 Ad Majoriam Dei Gloriam Our Lady of Perpetual Succour Ave Regina Caelorum, Ave Domina Angelorum. Salve Radix, Salve Porta, ex qua mundo Lux est orta ; Gaude Virgo Gloriosa, super omnes speciosa : Vale, O valde decora, et pro nobis Christum exora. V. Ora pro nobis sancta Dei Genetrix. R. Ut digni efficiamur promissionibus Christi. 3 THE PROBLEM WITH VATICAN II Michael Baker A study, in a series of essays, of the causes of the Second Vatican Council exposing their defects and the harmful consequences that have flowed in the teachings of popes, cardinals and bishops thereafter. This publication is a work of the website superflumina.org The author, Michael Baker, is a retired lawyer who spent some 35 years, first as a barrister and then as a solicitor of the Supreme Court of New South Wales. His authority to offer the commentary and criticism on the philosophical and theological issues embraced in the text lies in his having studied at the feet of Fr Austin M Woodbury S.M., Ph.D., S.T.D., foremost philosopher and theologian of the Catholic Church in Australia in the twentieth century, and his assistant teachers at Sydney’s Aquinas Academy, John Ziegler, Geoffrey Deegan B.A., Ph.D. -

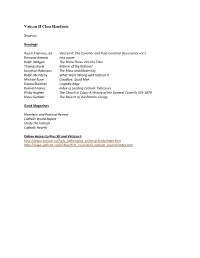

Vatican II Class Handouts

Vatican II Class Handouts Sources Readings Austin Flannery, ed. Vatican II: The Conciliar and Post-Conciliar Documents vol.1 Romano Amerio Iota unum Ralph Wiltgen The Rhine Flows into the Tiber Thomas Kocik Reform of the Reform? Jonathan Robinson The Mass and Modernity Ralph McInerny What Went Wrong with Vatican II Michael Rose Goodbye, Good Men Donna Steichen Ungodly Rage Kenneth Jones Index of Leading Catholic Indicators Philip Hughes The Church in Crisis: A History of the General Councils 325-1870 Klaus Gamber The Reform of the Roman Liturgy Good Magazines Homiletic and Pastoral Review Catholic World Report Inside the Vatican Catholic Hearth Online Access to Pius XII and Vatican II http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/pius_xii/encyclicals/index.htm http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/index.htm Benedict XVI to Roman Curia 22 December 2005 The last event of this year on which I wish to reflect here is the celebration of the conclusion of the Second Vatican Council 40 years ago. This memory prompts the question: What has been the result of the Council? Was it well received? What, in the acceptance of the Council, was good and what was inadequate or mistaken? What still remains to be done? No one can deny that in vast areas of the Church the implementation of the Council has been somewhat difficult, even without wishing to apply to what occurred in these years the description that St Basil, the great Doctor of the Church, made of the Church's situation after the Council of Nicea: he compares her situation to a naval battle in the darkness of the storm, saying among other things: "The raucous shouting of those who through disagreement rise up against one another, the incomprehensible chatter, the confused din of uninterrupted clamouring, has now filled almost the whole of the Church, falsifying through excess or failure the right doctrine of the faith..." (De Spiritu Sancto, XXX, 77; PG 32, 213 A; SCh 17 ff., p. -

Early Modern Catholic Reform and the Synod of Pistoia Shaun London Blanchard Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Eighteenth-Century Forerunners of Vatican II: Early Modern Catholic Reform and the Synod of Pistoia Shaun London Blanchard Marquette University Recommended Citation Blanchard, Shaun London, "Eighteenth-Century Forerunners of Vatican II: Early Modern Catholic Reform and the Synod of Pistoia" (2018). Dissertations (2009 -). 774. https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/774 EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY FORERUNNERS OF VATICAN II: EARLY MODERN CATHOLIC REFORM AND THE SYNOD OF PISTOIA by Shaun L. Blanchard, B.A., MSt. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2018 ABSTRACT EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY FORERUNNERS OF VATICAN II: EARLY MODERN CATHOLIC REFORM AND THE SYNOD OF PISTOIA Shaun L. Blanchard Marquette University, 2018 This dissertation sheds further light on the nature of church reform and the roots of the Second Vatican Council (1962–65) through a study of eighteenth-century Catholic reformers who anticipated Vatican II. The most striking of these examples is the Synod of Pistoia (1786), the high-water mark of “late Jansenism.” Most of the reforms of the Synod were harshly condemned by Pope Pius VI in the Bull Auctorem fidei (1794), and late Jansenism was totally discredited in the increasingly ultramontane nineteenth-century Catholic Church. Nevertheless, many of the reforms implicit or explicit in the Pistoian agenda – such as an exaltation of the role of bishops, an emphasis on infallibility as a gift to the entire church, religious liberty, a simpler and more comprehensible liturgy that incorporates the vernacular, and the encouragement of lay Bible reading and Christocentric devotions – were officially promulgated at Vatican II. -

The Holy See

The Holy See funeral Mass for Cardinal Ugo Poletti, former Vicar of the Eternal City HOMILY OF JOHN PAUL II Thursday, 27 February 1997 1. “Scio quod Redemptor meus vivit” (Jb 19:25). In the great silence that envelops the mystery of death, the voice of the ancient believer rises full of hope. Job implores salvation from the Living God, in whom every human event finds its meaning and definitive conclusion. “I shall see God ... and my eyes shall behold, and not another” (Jb 19:27), the inspired text continues, allowing a glimpse of the merciful face of the Lord at the end of the earthly pilgrimage. “My Redeemer .... will stand upon the earth”, the sacred author stresses, basing his expectations and the support of his hope on the assistance of the Almighty’s goodness. 2. This firm hope guided the path of our late and beloved Cardinal Poletti throughout his life among us: a hope that rested on his unshakeable and simple faith, learned at home and in the Christian community of Omegna, in the Diocese of Novara, where he was born over 82 years ago. It was precisely this relationship of trust and dialogue with the Lord that led young Ugo to perceive the divine call and to enter the seminary of Novara. It was this relationship, nourished by daily prayer, which sustained his first steps in his priestly ministry. He let himself be led by the Divine Master in every subsequent service to the Diocese of Novara, of which he was appointed ProVicar, and later, Vicar General. -

PITTSBURGH I/> H- I/I

Csí GO <M in PITTSBURGH i/> H- i/i > CO <C o M J O . Z O O <_> X o UJ tO C. 'O 'O >■ ^ 2 o <t UJ l/l latebllahed In 1844: Americo’» Oldest Catholic N ew tpopr In Conttnuom Publication ÛL D h — I— 144 Year, CXUV 2 ? o « cents Friday, February 10,1989 ” a _ i a . D iocese prepares for Feb. 13 ordination Bishop Bishop Donald W. Ceremonies scheduled Feb. 13, Priest ready W uerl discusses the ap pointment of Bishop- cable stations to televise event for new role elect W inter and states that his help will come By PATRICIA BARTOS as aux. bishop quickly and will be seen Bishop-elect W illiam J. W inter will be ordained as the fifth auxiliary throughout the diocese. bishop in the history of the diocese In ceremonies Monday, Feb. 13, at B y PATRICIA BARTOS 3 p.m . in St. Paul Cathedral. Oakland. PITTSBURGH — As he ................................... P a g e 4 Consecrator for the ordination will be Bishop Donald W . W uerl. with prepares for ordination as the Aux. Bishop John B. McDowell and Greensburg Bishop Anthony diocese's next auxiliary bishop on Bosco (a former auxiliary bishop in Pittsburgh) as co-conaecrators. Feb. 13. Father W illiam W inter is Bishop McDowell Is general chairm an for the ordination. gradually becoming comfortable Philadelphia Archbishop (and former Pittsburgh bishop) Anthony with the reality of his new role. Bevilacqua will preside. In the presence of Archbishop Pio Laghl, "I've sort of come from a feeling apostolic pro-nuncio to the U.S. -

Evidence from 500 Years of Betting on Papal Conclaves

Forecasting the Outcome of Closed-Door Decisions: evidence from 500 years of betting on papal conclaves October 2014 Leighton Vaughan Williams Professor of Economics and Finance Nottingham Business School Nottingham Trent University Burton Street Nottingham NG1 4BU United Kingdom Tel: +44 115 848 6150 Email: [email protected] David Paton* Professor of Industrial Economics Nottingham University Business School Wollaton Road Nottingham NG8 1BB United Kingdom Tel: +44 115 846 6601 Fax: +44 115 846 6667 Email: [email protected] * corresponding author Acknowledgements We would like to thank participants at a Nottingham Trent University Staff Seminar and at Georgia State University’s ‘Center for the Economic Analysis of Risk’ Workshop, held in January, 2014 at the University of Cape Town, for several helpful comments and suggestions. Forecasting the Outcome of Closed-Door Decisions: evidence from 500 years of betting on papal conclaves. Abstract Closed-door decisions may be defined as decisions in which the outcome is determined by a limited number of decision-makers and where the process is shrouded in at least some secrecy. In this paper, we examine the use of betting markets to forecast on particular closed- door decision, the election of the Pope. Within the context of 500 years of papal election betting, we employ a unique dataset of betting on the 2013 papal election to investigate how new public information is incorporated into the betting odds. Our results suggest that the market was generally unable to incorporate effectively such information. We venture some possible explanations for our findings and offer suggestions for further research into the prediction and predictability of other ‘closed-door’ decisions. -

March 10, 2019

First Sunday in Lent March 10, 2019 Bronx, New York I AM THE WAY AND THE TRUTH AND THE LIFE. HOLY MASS SCHEDULE Pastor Saturday: 8:00 a.m. (Italian), 9:00 a.m. (English) Rev. Nikolin Pergjini 5:30 p.m. (Albanian), 7:00 p.m. (English) Parochial Vicar Sunday: 8:00 a.m. (Italian), Rev. Urbano Rodrigues 9:00 a.m. (Spanish - Auditorium) 9:15 a.m., 10:30 a.m., 12 noon (English), 12:00 p.m. (Creole - Chapel in Center), Sunday Associate Rev. Msgr. Frederick J. Becker 1:15 p.m. (Spanish) Weekdays: 8:00 a.m. (Italian), 9:00 a.m. (English), Rev. Joseph Koterski, S.J. Thursdays: 7:00 p.m. (Spanish) Rev. Richard Veras Deacon Santos Arroyo Eucharistic Adoration: Monday-Friday 9:30-12 noon, Thursday 6-7:00 p.m., Saturday 9:30 a.m.-12 noon & Deacon Carlos Mercado First Friday of the Month 6:00-7:30 p.m. Director of Music - Jhasoa O. Agosto Confession: Saturdays 3:00- 4:00 p.m. & 6:30-7:00 p.m. Parish Website: WWW.STLUCYBRONX.ORG VOCATIONS Parish E-mail: [email protected] Is God calling you to the priesthood or religious life? Speak to RECTORY: 718-882-0710 Fax: 718-882-8876 one of our priests or call the Archdiocese Vocations Office at 833 Mace Avenue Bronx, NY 10467 (914) 968-1340. Monday thru Saturday - 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 ————————————————————————————————————————— BAPTISMS/WEDDINGS RELIGIOUS EDUCATION: 718-882-0710 x19 Please make arrangements with a Parish Priest at the Rectory Isabel Arroyo, Coordinator office at least six months in advance. -

Letter to Cardinals Compl. En-1

BEABEATIFICATIFICATIONTION OFOF PAUL VI? - Letter to Cardinals - BEATIFICATION OF PAUL VI? - Letter to the Cardinals - Your Eminence, I had read in the press that on December 11 the Cardinals and Bishops, overcoming the obstacle of the theologians, will give their “yes” for the beatification of Pope Paul VI, despite the fact that he never had, while he was living, any reputation for holiness, but instead, was primarily responsible for all the cur- rent troubles of the Church, and I even dare to say that the result of his pontificate was really catastrophic! Allow me then, to concede on what had been reported, in bold print, in “Avvenire” of March 19, 1999, page 17, about Monsignor Montini: “Ruini makes a Profile of the Pope (Paul VI) that changed the Church.” How very true! ... We proved it with our “Montinian Trilogy,” which was never found to be false or inva- lid by my opponents who always limited themselves to public ridicule, insults and trivialities without ever denouncing in public, the “how,” “where,” and “why” of our arguments and our documents that would be contrary to the truth. Certainly, to tell the “truth” is not wrong, even about the person of Paul VI, because he has become part of History, so his entire life can be studied without hesitation or misinformation, without putting a halo on his head, which would mean to put it around his “revolution” carried out by Freemasonry, through him, in the name of Vatican II. *** It must be, then, a duty to give an outline of his alleged virtues necessary for a beatification.