James William Gleeson Archbishop of Adelaide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agenda Paolina

2021 AGENDA PAOLINA con riflessioni quotidiane dagli scritti del beato Giacomo Alberione Anno LXV © SASP s.r.l., 2020 Copertina di Ulysses Navarro, ssp “Gesù Maestro Via Verità Vita”: realizzazione grafica di Ulysses Navarro, ssp PRESENTAZIONE «Ut unum sint». Dalla Parola l’unità. La comunione con la Trinità come senso ultimo della nostra vita aposto- lica, del nostro vivere insieme per l’evangelizzazione e del nostro operare perché l’umanità possa incontrare Gesù Maestro. Ma anche la comunione come stile di vita e mentalità, continuamente rinnovata da Cristo e dalle nuove frontiere della missione paolina. Questo essere “uno” esprime il senso del “corpo”, della Famiglia Paolina pronta a operare insieme, a pregare insieme per l’umani- tà, a generare nuovi percorsi di vita. Lo sfondo dei brani scelti per l’Agenda Paolina 2021 è la sinodalità, tema tanto caro a Papa Francesco e neces- sario per vivere la nostra missione. “Camminare insieme”, nella diversità dei doni, è un atteggiamento profondo ma anche un modo di operare. “Sinodali” lo siamo nel vivere la nostra missione come Famiglia, quando la Parola di Dio ci raggiunge, ci conquista e dà nuovi significati al no- stro essere in mezzo all’umanità di oggi. La vita del Beato Giacomo Alberione, nel Centenario della sua professione religiosa (5 ottobre), è per noi un esempio perché impre- gnata di incontri, di reciprocità, di ascolto, di coinvolgi- mento… Il suo amore alla Scrittura, e in particolare alle Lettere di san Paolo, ha plasmato il suo modo di vivere da apostolo e di esserci padre. Durante quest’anno celebriamo il 50° della morte del Primo Maestro e portiamo a termine, proprio il 26 no- vembre, l’Anno Biblico di Famiglia Paolina. -

SA Police Gazette 1946

This sampler file contains various sample pages from the product. Sample pages will often include: the title page, an index, and other pages of interest. This sample is fully searchable (read Search Tips) but is not FASTFIND enabled. To view more samplers click here www.gould.com.au www.archivecdbooks.com.au · The widest range of Australian, English, · Over 1600 rare Australian and New Zealand Irish, Scottish and European resources books on fully searchable CD-ROM · 11000 products to help with your research · Over 3000 worldwide · A complete range of Genealogy software · Including: Government and Police 5000 data CDs from numerous countries gazettes, Electoral Rolls, Post Office and Specialist Directories, War records, Regional Subscribe to our weekly email newsletter histories etc. FOLLOW US ON TWITTER AND FACEBOOK www.unlockthepast.com.au · Promoting History, Genealogy and Heritage in Australia and New Zealand · A major events resource · regional and major roadshows, seminars, conferences, expos · A major go-to site for resources www.familyphotobook.com.au · free information and content, www.worldvitalrecords.com.au newsletters and blogs, speaker · Free software download to create biographies, topic details · 50 million Australasian records professional looking personal photo books, · Includes a team of expert speakers, writers, · 1 billion records world wide calendars and more organisations and commercial partners · low subscriptions · FREE content daily and some permanently The resolution of this sampler has been reduced from the original on CD to keep the file smaller for download. South Australian Police Gazette 1946 Ref. AU5103-1946 ISBN: 978 1 921494 85 7 This book was kindly loaned to Archive CD Books Australia by the South Australia Police Historical Society www.sapolicehistory.org Navigating this CD To view the contents of this CD use the bookmarks and Adobe Reader’s forward and back buttons to browse through the pages. -

Annual Report and Financial Statements

HIERARCHY GENERAL PURPOSES TRUST FINANCIAL STATEMENTS YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2018 Page 1 HIERARCHY GENERAL PURPOSES TRUST REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2018 CONTENTS Page Trustees and Other Information 3 Report of the Trustees 4 Independent Auditors Report 12 Statement of Financial Activities 14 Balance Sheet 15 Cashflow Statement 16 Statement of Accounting Policies 17 Notes to the Financial Statements 19 Page 2 HIERARCHY GENERAL PURPOSES TRUST TRUSTEE AND OTHER INFORMATION TRUSTEES + Eamon Martin + Kieran O'Reilly SMA + Diarmuid Martin + Michael Neary + Michael Smith Resigned 02/09/2018 + John Buckley + John Kirby + Leo O'Reilly Resigned 31/12/2018 + John McAreavey Resigned 26/03/2018 + Donal McKeown + John Fleming + Denis Brennan + Brendan Kelly + Noel Treanor + William Crean + Brendan Leahy + Raymond Browne + Denis Nulty + Francis Duffy + Kevin Doran + Alphonsus Cullinan + Fintan Monahan + Alan McGuckian SJ Michael Ryan Resigned 11/03/2018 MIchael Mclaughlin Resigned 11/02/2018 Joseph McGuinness Dermot Meehan App 13/02/2018 + Dermot Farrell App 11/03/2018 + Philip Boyce App 26/03/2018 + Thomas Deenihan App 02/09/2018 EXECUTIVE ADMINISTRATOR Harry Casey FINANCE AND GENERAL + Francis Duffy PURPOSES COUNCIL + John Fleming + Michael Smith (Resigned 02/09/2018) Derek Staveley Stephen Costello Sean O'Dwyer Alice Quinn Anthony Harbinson Aideen McGinley Jim McCaffrey CHARITY NUMBER CHY5956 CHARITY REGULATOR NUMBER 20009861 PRINCIPAL OFFICE Columba Centre Maynooth Co. Kildare AUDITORS: Crowe Ireland Chartered Accountants and Statutory Audit Firm Marine House Clanwilliam Court Dublin 2 BANKERS: AIB Plc Ulster Bank Bank of Ireland INVESTMENT MANAGERS: Davy Group Dublin 2 SOLICITORS: Mason Hayes & Curran South Bank House Dublin 4 Page 3 HIERARCHY GENERAL PURPOSES TRUST REPORT OF THE TRUSTEES FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2018 The Trustees present their annual report and the financial statements of the Hierarchy General Purposes Trust (HGPT) for the year ended 31 December 2018. -

Patrick Michael O'regan Dd

Celebration of the Eucharist and Installation of the Ninth Archbishop of Adelaide the most reverend Patrick Michael O’Regan dd Monday 25 May 2020 St Francis Xavier’s Cathedral, Adelaide Solemnity of Our Lady Help of Christians Archdiocese of Adelaide St Francis Xavier’s Cathedral, Adelaide Image: Stained glass windows - St Francis Xavier’s Cathedral Most Rev Patrick Michael O’Regan dd Ninth Archbishop of Adelaide Patrick Michael O’Regan was born in Perthville following the retirement of Bishop Patrick NSW, a small rural village 10km south of Dougherty in November 2008. Bathurst, on Wednesday 8th October 1958. When Bishop Michael McKenna was installed His parents, the late Colin Michael O’Regan in June 2009, Fr O’Regan become Diocesan and the late Alice Daphne O’Regan (nee Chancellor and in 2010-14 was Dean of the Dulhunty) raised four children, Stephen, Cathedral and was appointed Vicar General in Laurence, Patrick and Louise. 2012. He was educated at St Joseph’s Primary, Fr O’Regan was a member of the National Perthville by the Sisters of St Joseph, and at Liturgical Council and the diocesan St Stanislaus Secondary College, Bathurst, coordinator for the ongoing formation of by the Vincentian Order. He studied for priests and permanent deacons. the priesthood at St Columba College, Springwood, and St Patrick’s College, Manly, He was appointed ninth Bishop of Sale by before being ordained a priest for Bathurst Pope Francis on 4th December 2014, the 51st Diocese in 1983. He served as assistant priest at anniversary of the declaration of Sacrosanctum Lithgow, Cowra, Orange and Bathurst before concilium, the Constitution on the Sacred undertaking higher studies in France in 1994- Liturgy. -

Politics, Church and the Common Good

Politics, Church and the Common Good Andrew Bradstock and Hilary Russell In an article published in the UK religious newspaper Church Times in 2015, the British academic and political thinker, Maurice Glasman, reflected upon the global financial crash of 2008. Suggesting that both ‘liberal economists’ and ‘state socialists’ could only understand the crisis as being ‘fundamentally about money’, with the solution being either to spend more or less of it, Glasman noted how the churches had sought to make a deeper analysis. While the ‘prevailing paradigms’ that governed our thinking about economics and politics had no capacity for recognising ‘sin’ as a contributing factor to the crisis, church leaders such as the Pope and Archbishop of Canterbury had ‘tried to insert the concept of the “good” into economic calculation’ – and in so doing had retrieved ‘some forgotten ideas, carried within the Church but rejected by secular ideologies, which turn out to have a great deal more rational force than invisible hands and spending targets.’1 By ‘forgotten ideas’ Glasman meant the core principles of Catholic Social Thought (CST), a collection of papal encyclicals spanning the last 125 years which constitute the authoritative voice of the Catholic Church on social issues. Drawing upon CST had enabled the pontiff and archbishop not only to challenge the narratives of the political Left and Right, to endorse neither state centralisation nor the centralisation of capital, but rather to highlight values such as human dignity, interdependence and care of creation. Importantly they had drawn attention to the need for markets to promote the wellbeing of all, the ‘common good’. -

A Report of the House of Bishops' Working Party on Women in the Episcopate Church Ho

Women Bishops in the Church of England? A report of the House of Bishops’ Working Party on Women in the Episcopate Church House Publishing Church House Great Smith Street London SW1P 3NZ Tel: 020 7898 1451 Fax: 020 7989 1449 ISBN 0 7151 4037 X GS 1557 Printed in England by The Cromwell Press Ltd, Trowbridge, Wiltshire Published 2004 for the House of Bishops of the General Synod of the Church of England by Church House Publishing. Copyright © The Archbishops’ Council 2004 Index copyright © Meg Davies 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or stored or transmitted by any means or in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system without written permission, which should be sought from the Copyright Administrator, The Archbishops’ Council, Church of England, Church House, Great Smith Street, London SW1P 3NZ. Email: [email protected]. The Scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright © 1989, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA, and are used by permission. All rights reserved. Contents Membership of the Working Party vii Prefaceix Foreword by the Chair of the Working Party xi 1. Introduction 1 2. Episcopacy in the Church of England 8 3. How should we approach the issue of whether women 66 should be ordained as bishops? 4. The development of women’s ministry 114 in the Church of England 5. Can it be right in principle for women to be consecrated as 136 bishops in the Church of England? 6. -

Education Resource

Education Resource This education resource has been developed by the Art Gallery of New South Wales and is also available online An Art Gallery of New South Wales exhibition toured by Museums & Galleries NSW DRAWING ACTIVITIES Draw with black pencil on white paper then with white pencil on black paper. How does the effect differ? Shade a piece of white paper using a thick piece of charcoal then use an eraser to draw into the tone to reveal white lines and shapes. Experiment with unconventional materials such as shoe polish and mud on flattened cardboard boxes. Use water on a paved surface to create ephemeral drawings. Document your drawings before they disappear. How do the documented forms differ from the originals? How did drawing with an eraser, shoe polish, mud and water compare to drawing with a pencil? What do you need to consider differently as an artist? How did handling these materials make you feel? Did you prefer one material to another? Create a line drawing with a pencil, a tonal drawing with charcoal and a loose ink drawing with a brush – all depicting the same subject. Compare your finished drawings. What were some of the positive and negatives of each approach? Is there one you prefer, and why? Draw without taking your drawing utensil off the page. What was challenging about this exercise? Draw something from observation without looking down at your drawing. Are you pleased with the result? What did you learn? Create a series of abstract pencil drawings using colours that reflect the way you feel. -

National Conference of Directors for Ongoing Formation Resources

National Conference of National Conference of Directors for Ongoing Directors for Ongoing Formation Formation Resources Resources CONTENTS CONTENTS 1.SPEAKERS 1.SPEAKERS 2.RETREATS & VENUES 2.RETREATS & VENUES 3.HONORARIUM 3.HONORARIUM 4.PUBLICATIONS 4.PUBLICATIONS 1.SPEAKERS 1.SPEAKERS Alan Griffiths ‐ “The new translation of The Roman Missal” Alan Griffiths ‐ “The new translation of The Roman Missal” Alan Morris ‐ "Praying With Your People: Liturgy in a Changing Church" Alan Morris ‐ "Praying With Your People: Liturgy in a Changing Church" Alan White OP ‐ "The Face of Priesthood in a Broken World" Alan White OP ‐ "The Face of Priesthood in a Broken World" Alistair Stewart‐Sykes ‐ "The Lords Prayer According to the Fathers" Alistair Stewart‐Sykes ‐ "The Lords Prayer According to the Fathers" Andrew Wingate, St Philip's Centre, Leicester – “Mutely‐faith” Andrew Wingate, St Philip's Centre, Leicester – “Mutely‐faith” Anthony Doe ‐ "The Priest as Physician of the Soul" Anthony Doe ‐ "The Priest as Physician of the Soul" Ashley Beck – “The Permanent Diaconate” Ashley Beck – “The Permanent Diaconate” Austin Garvey – “Ethnic Chaplains” Austin Garvey – “Ethnic Chaplains” Bede Leach OSB ‐ “Spiritual Director” Bede Leach OSB ‐ “Spiritual Director” Ben Bano – “There's no Health without Mental Health” Ben Bano – “There's no Health without Mental Health” Bernard Longley – “Under 5's and Clergy Retreat” Bernard Longley – “Under 5's and Clergy Retreat” Bill Huebsch, USA – “In‐Service Training” Bill Huebsch, USA – “In‐Service Training” Bishop Declan -

BA Santamaria

B. A. Santamaria: 'A True Believer'? Brian Costar and Paul Strangio* By revisiting the existing scholarship deeding with Santamaria's career and legacy, as well as his own writings, this article explores the apparent tension between the standard historical view that Santamaria attempted to impose an essentially 'alien philosophy' on the Labor Party, and the proposition articulated upon his death that he moved in a similar ideological orbit to the traditions of the Australian labour movement. It concludes that, while there were occasional points of ideological intersection between Santamaria and Australian laborism, his inability to transcend the particular religious imperatives which underpinned his thought and action rendered'him incompatible with that movement. It is equally misleading to locate him in the Catholic tradition. Instead, the key to unlocking his motives and behaviour was that he was a Catholic anti-Modernist opposed not only to materialist atheism but also to religious and political liberalism. It is in this sense that he was 'alien'both to labor ism, the majorityofthe Australian Catholic laity and much of the clergy. It is now over six years since Bartholomew Augustine 'Bob' Santamaria died on Ash Wednesday 25 February 1998—enough time to allow for measured assessments of his legacy. This article begins by examining the initial reaction to his death, especially the eagerness of many typically associated with the political Left in Australia rushing to grant Santamaria a kind of posthumous pardon. Absolving him of his political sins may have been one thing; more surprising was the readiness to ideologically embrace the late Santamaria. The suggestion came from some quarters, and received tacit acceptance in others, that he had moved in a similar ideological orbit to the traditions of the Australian labour movement Such a notion sits awkwardly with the standard historical view that Santamaria had attempted to impose an essentially 'alien philosophy* on the Labor Party, thus explaining why his impact on labour politics proved so combustible. -

Mary Colwell and Austen Ivereigh: Has the Pandemic Renewed Our Relationship with Nature?

Peter Hennessy How Keir Starmer has changed the rules of engagement at Westminster THE INTERNATIONAL 23 MAY 2020 £3.80 CATHOLIC WEEKLY www.thetablet.co.uk Est. 1840 Wild faith Mary Colwell and Austen Ivereigh: Has the pandemic renewed our relationship with nature? John Wilkins on the faith and doubt of Graham Greene Death at Dunkirk The last days of the fi rst Catholic chaplain to be killed in action Peter Stanford interviews Ann Patchett • Adrian Chiles celebrates football’s family values 01_Tablet23May20 Cover.indd 1 19/05/2020 18:48 02_Tablet23May20 Leaders.qxp_Tablet features spread 19/05/2020 18:30 Page 2 THE INTERNATIONAL CATHOLIC WEEKLY THE TABLET FOUNDED IN 1840 POST-LOCKDOWN he coronavirus lockdown has coincided with and beyond the care it has for everyone whose MENTAL HEALTH a welcome change in the public perception of vocation requires them to put themselves in harm’s T mental illness. This has in turn highlighted way for the sake of others. There is an excellent ENDING the likelihood that underneath the Catholic Mental Health Project website supported by coronavirus pandemic lies a hidden psychiatric one, the Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales, but it THE which remains largely untreated. Social distancing, does not focus on the emotional wellbeing of priests as isolation, and the general government message to such. More needs to be known about this issue: for STIGMA people to “stay at home” where possible have instance because parish priests are men who tend to neutralised one of society’s main defences against live alone, are they more resilient when called upon to mental ill-health, namely the influence of other isolate themselves, or less so? How important to their people. -

Fourth Plenary Council of Australia and New Zealand, 4-12 September 1937

Fourth Plenary Council of Australia and New Zealand, 4-12 September 1937 PETER J WILKINSON This is Part 1 of the seventh in the series of articles looking at the particular councils of the Catholic Church in Australia held between 1844 and 1937. It examines the background and factors leading to the Fourth Plenary Council of Australia and New Zealand held in Sydney in September 1937, which brought all the particular churches of both nations for the second time. Part 2 will appear in the Winter edition of The Swag. After the Australian Plenary Council in 1905, only four particular (provincial and plenary) councils were convened in the English-speaking mission territories under the jurisdiction of the Sacred Congregation de Propaganda Fide (‘Propaganda’): the Provincial Councils of Tuam and Cashel in Ireland held in 1907, the Provincial Council of Melbourne in 1907, and the 4th Plenary Council of Australia and New Zealand in 1937. Developments in church governance, 1905-1937 Fewer councils were held in the English-speaking mission territories in this period as Pope Pius X (1903-1914) had announced in his 1908 Constitution Sapienti Consilio that the hierarchies of Great Britain, Canada, and the United States were ‘established’ and the churches there were no longer considered ‘mission territories’. Australia and New Zealand, however, were to remain mission territories under the jurisdiction of Propaganda.1 In 1911, Cardinal Patrick Moran died, and was succeeded by his coadjutor, Archbishop Michael Kelly (1911-40). Moran had convened three plenary councils in 1885, 1895 and 1905, been Australia’s most powerful Catholic prelate, and for 27 years had functioned as the Holy See’s de facto apostolic delegate for Australia and New Zealand. -

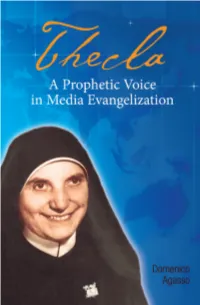

Read a Sample

Biography How can we respond when God seems to ask the impossible of us? Venerable Thecla Merlo (1894–1964) must have asked herself this question many times. Born to a simple farming family, Thecla was not highly educated, and she was plagued by poor health. In 1915, however, she embarked on an extraordinary adventure that would place her at the forefront of a new charism in the Church. This young seamstress would be among the first Daughters of St. Paul, dedicated to proclaiming the Gospel with all forms of media. Thecla’s uncommon gifts, unshakable confidence in God, and broad vision made her a prophetic voice for evangelization. One hundred years later, her legacy continues to inspire men and women around the globe. “How beautiful and holy it is to communicate Jesus to others—the Jesus whom we want to always carry in the center of our hearts.” — Venerable Mother Thecla Merlo $14.95 U.S. ISBN 0-8198-7527-9 Thecla A Prophetic Voice in Media Evangelization by Domenico Agasso BOOKS & MEDIA Boston The Scripture quotations in this publication are from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, Catholic edition, copyright © 1965 and 1966 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A., and are used by permission. All rights reserved. Originally published as Tecla: Voce profetica nella comunicazione by Domenico Agasso, Paoline Editoriale Libri © Figlie di San Paolo, 2014, via Francesco Albani— 20149 Milano (Italy) English translation by John Moore, St. Paul MultiMedia Productions U.K., Middle Green, Slough SL3 6BS U.S.A.