Insulinde Selected Translations from Dutch Writers of Three Centuries on the Indonesian Archipelago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

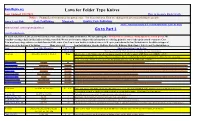

Laws for Folder Type Knives Go to Part 1

KnifeRights.org Laws for Folder Type Knives Last Updated 1/12/2021 How to measure blade length. Notice: Finding Local Ordinances has gotten easier. Try these four sites. They are adding local government listing frequently. Amer. Legal Pub. Code Publlishing Municode Quality Code Publishing AKTI American Knife & Tool Institute Knife Laws by State Admins E-Mail: [email protected] Go to Part 1 https://handgunlaw.us In many states Knife Laws are not well defined. Some states say very little about knives. We have put together information on carrying a folding type knife in your pocket. We consider carrying a knife in this fashion as being concealed. We are not attorneys and post this information as a starting point for you to take up the search even more. Case Law may have a huge influence on knife laws in all the states. Case Law is even harder to find references to. It up to you to know the law. Definitions for the different types of knives are at the bottom of the listing. Many states still ban Switchblades, Gravity, Ballistic, Butterfly, Balisong, Dirk, Gimlet, Stiletto and Toothpick Knives. State Law Title/Chapt/Sec Legal Yes/No Short description from the law. Folder/Length Wording edited to fit. Click on state or city name for more information Montana 45-8-316, 45-8-317, 45-8-3 None Effective Oct. 1, 2017 Knife concealed no longer considered a deadly weapon per MT Statue as per HB251 (2017) Local governments may not enact or enforce an ordinance, rule, or regulation that restricts or prohibits the ownership, use, possession or sale of any type of knife that is not specifically prohibited by state law. -

Teaching Tales from Djakarta.Pdf (636.2Kb)

2 Table of Contents Introduction…………………………………………………………………….………… 3 Notes on Teaching Tales from Djakarta ………………………………………………… 5 Biography ………………………………………………………………………………... 8 History ………………………………………………………………………...……...… 11 Critical Lenses ……………………………………………………………………..…... 18 Social Realism ………………………………………………….……………… 18 Colonial and Postcolonial Theory.…………………………………………..….. 21 The National Allegory ……………………………………………………….… 26 Nostalgia ……………………………………………………………...….….…. 30 Study Guide …………………………………………………………………….……… 33 Bibliography & Resources ………………………………………………………..……. 43 List of Images 1. Pramoedya, 1950’s From A Teeuw, Modern Indonesian Literature. Courtesy of KITLV . Used by permission 2. Pramoedya, 1990’s From Indonesia, 1996.Courtesy of Benedict R. O’G. Anderson and Cornell Southeast Asia Program Publications. Used by permission. 3. Indo-European woman and her children, presumably in Bandoeng Courtesy of KITLV. Used by permission. 4. Ketjapi player in Jakarta Courtesy of KITLV. Used by permission. 5. G.E. Raket and his girlfriend, presumably in Batavia Courtesy of KITLV. Used by permission. 6. Prostitute with child camping in and underneath old railway carriages at Koningsplein-Oost [East King's Square] in Jakarta Courtesy of KITLV. Used by permission 3 Introduction Pramoedya Ananta Toer has long been one of the most articulate voices coming from decolonized Indonesia. A prolific author, Pramoedya has written short fiction, novels, histories, and social and cultural commentary about his native land. He is frequently mentioned as a leading candidate for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Pramoedya’s perennial candidacy for this award is almost certainly based on his epic tetralogy about the birth of Indonesian nationalism, the Buru quartet. In these novels, which tell the story of Raden Mas Minke, a native journalist and founding member of several political and social organizations in the Indies, Pramoedya draws a vivid picture of the colonial period: approximately 1900-1915. -

ABSTRAK Etnik Bajau Merupakan Etnik Kedua Terbesar Di Kota Belud

IKONOGRAFI MOTIF PADA SENJATA TRADISIONAL GAYANG ETNIK BAJAU SAMA DI KOTA BELUD Mohd Farit Azamuddin bin Musa Humin Jusilin Universiti Malaysia Sabah [email protected] ABSTRAK Etnik Bajau merupakan etnik kedua terbesar di Kota Belud. DI daerah ini, sebahagian petaninya menjalankan kegiatan pertanian dan penternakan untuk meneruskan kelangsungan hidup. Bagi kaum lelaki, senjata amat penting dalam kehidupan seharian kerana kegunaannya sebagai alat untuk memburu, bercucuk tanam dan utiliti harian. Jenis senjata yang dihasilkan ialah pida’ (parang pendek), guk (parang), lading (pisau), keris, kagayan (parang panjang), beladau (parang jenis sabit) dan gayang (pedang). Fungsi pida’, guk beladau dan lading lazimnya digunakan untuk aktiviti harian seperti bercucuk tanam dan memburu. Karis, kagayan, dan gayang pula digunakan sebagai alat untuk mempertahankan diri. Setiap senjata memainkan peranan penting dalam kehidupan masyarakat. Walaupun begitu, setiap senjata yang ditempa boleh dimanipulasi sebagai senjata untuk melindungi diri daripada ancaman bahaya terutamanya daripada haiwan buas dan berbisa. Pelbagai jenis motif dan hiasan pada senjata melalui olahan idea yang diambil daripada persekitaran mereka. Tujuan kajian ini dihasilkan adalah untuk meneliti bentuk dan motif pada senjata tradisional dari segi visual dan istilahnya. Kajian lapangan (fieldwork) dijalankan di daerah Kota Belud khususnya di Kampung Siasai Jaya, Kampung Siasai Dundau, Kampung Siasai Kumpang, dan Kampung Tengkurus. Data yang diperolehi adalah berbentuk kualitatif dengan mengaplikasi indikator teori ikonografi daripada Panofsky (1939). Penelitian tentang data kajian melalui tiga peringkat iaitu identifikasi, analisis formalistik dan interpretasi makna. Motif yang dikenal pasti terbahagi kepada dua kategori iaitu bersifat organik dan geometri yang merangkumi motif flora, fauna, dan alam sekitar. Pengkaji juga melakukan pengesahan data bersama beberapa informan. -

A Comparative Study of Pramoedya Ananta Toer's

COLONIAL IDENTITIES DURING COLONIALISM IN INDONESIA: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF PRAMOEDYA ANANTA TOER’S CHILD OF ALL NATIONS AND MULTATULI’S MAX HAVELAAR AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By LETYZIA TAUFANI Student Number: 054214109 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2008 i ii iii “Nothing is more dangerous than an idea especially when we have only one.” Paul Claudel iv This Undergraduate Thesis Dedicated to: My Daughter Malia Larasati Escloupier and My Husband Cédric v LEMBAR PERNYATAAN PERSETUJUAN PUBLIKASI KARYA ILMIAH UNTUK KEPENTINGAN AKADEMIS Yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini, saya mahasiswa Universitas Sanata Dharma: Nama : Letyzia Taufani Nomor Mahasiswa : 054214109 Demi pengembangan ilmu pengetahuan, saya memberikan kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma karya ilmiah saya yang berjudul: COLONIAL IDENTITIES DURING COLONIALISM IN INDONESIA: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF PRAMOEDYA ANANTA TOER’S CHILD OF ALL NATIONS AND MULTATULI’S MAX HAVELAAR Beserta perangkat yang diperlukan (bila ada). Dengan demikian saya memberikan kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma hak untuk menyimpan, mengalihkan dalam bentuk media lain, mengelolanya dalam bentuk pangkalan data, mendistribusikan secara terbatas, dan mempublikasikannya di internet atau media lain untuk kepentingan akademis tanpa perlu meminta ijin dari saya maupun memberikan royalty kepada saya selama tetap mencantumkan nama saya sebagai penulis. Demikian pernyataan ini yang saya buat dengan sebenarnya. Dibuat di Yogyakarta Pada tanggal : 1 Desember 2008 Yang menyatakan (Letyzia Taufani) vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank and express my greatest gratitude to all of those who gave me guidance, strength and opportunity in completing this thesis. -

Scraps of Hope in Banda Aceh

Marjaana Jauhola Marjaana craps of Hope in Banda Aceh examines the rebuilding of the city Marjaana Jauhola of Banda Aceh in Indonesia in the aftermath of the celebrated SHelsinki-based peace mediation process, thirty years of armed conflict, and the tsunami. Offering a critical contribution to the study of post-conflict politics, the book includes 14 documentary videos Scraps of Hope reflecting individuals’ experiences on rebuilding the city and following the everyday lives of people in Banda Aceh. Scraps of Hope in Banda Aceh Banda in Hope of Scraps in Banda Aceh Marjaana Jauhola mirrors the peace-making process from the perspective of the ‘outcast’ and invisible, challenging the selective narrative and ideals of the peace as a success story. Jauhola provides Gendered Urban Politics alternative ways to reflect the peace dialogue using ethnographic and in the Aceh Peace Process film documentarist storytelling. Scraps of Hope in Banda Aceh tells a story of layered exiles and displacement, revealing hidden narratives of violence and grief while exposing struggles over gendered expectations of being good and respectable women and men. It brings to light the multiple ways of arranging lives and forming caring relationships outside the normative notions of nuclear family and home, and offers insights into the relations of power and violence that are embedded in the peace. Marjaana Jauhola is senior lecturer and head of discipline of Global Development Studies at the University of Helsinki. Her research focuses on co-creative research methodologies, urban and visual ethnography with an eye on feminisms, as well as global politics of conflict and disaster recovery in South and Southeast Asia. -

A Synopsis of the Pre-Human Avifauna of the Mascarene Islands

– 195 – Paleornithological Research 2013 Proceed. 8th Inter nat. Meeting Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution Ursula B. Göhlich & Andreas Kroh (Eds) A synopsis of the pre-human avifauna of the Mascarene Islands JULIAN P. HUME Bird Group, Department of Life Sciences, The Natural History Museum, Tring, UK Abstract — The isolated Mascarene Islands of Mauritius, Réunion and Rodrigues are situated in the south- western Indian Ocean. All are volcanic in origin and have never been connected to each other or any other land mass. Despite their comparatively close proximity to each other, each island differs topographically and the islands have generally distinct avifaunas. The Mascarenes remained pristine until recently, resulting in some documentation of their ecology being made before they rapidly suffered severe degradation by humans. The first major fossil discoveries were made in 1865 on Mauritius and on Rodrigues and in the late 20th century on Réunion. However, for both Mauritius and Rodrigues, the documented fossil record initially was biased toward larger, non-passerine bird species, especially the dodo Raphus cucullatus and solitaire Pezophaps solitaria. This paper provides a synopsis of the fossil Mascarene avifauna, which demonstrates that it was more diverse than previously realised. Therefore, as the islands have suffered severe anthropogenic changes and the fossil record is far from complete, any conclusions based on present avian biogeography must be viewed with caution. Key words: Mauritius, Réunion, Rodrigues, ecological history, biogeography, extinction Introduction ily described or illustrated in ships’ logs and journals, which became the source material for The Mascarene Islands of Mauritius, Réunion popular articles and books and, along with col- and Rodrigues are situated in the south-western lected specimens, enabled monographs such as Indian Ocean (Fig. -

Perencanaan Tata Guna Lahan Desa Balaroa Pewunu

Perencanaan Tata Guna Lahan Desa Balaroa Pewunu Bab I Pendahuluan 1.1 Latar Belakang Desa Balaroa Pewunu merupakan desa baru yang memisahkan diri dari desa induk Pewunu pada tahun 2012, berdirinya desa ditetapkan pada 20 november 2012 melaui Perda Kabupaten Sigi Nomor 41 tahun 2012 tentang Pemekaran Desa Balaroa Pewunu Kecamatan Dolo Barat Sigi Sulawesi Tengah. Secara geografis, desa Balaroa Pewunu berada di sebelah barat ibu kota kabupaten Sigi dengan melalui jalan poros Palu-Kulawi, untuk kedudukan atronomisnya terdapat pada titik koordinat S 1 °01’37" Lintang Selatan dan E 119°51'37 Bujur Timur. Luas desa Balaroa Pewunu (indikatif) 217,57 Ha berdasarkan hasil pemetaan partisipatif yang dilakukan oleh warga pada tahun 2019 dengan topografi atau rupa bumi umumnya dalam bentuk daratan yang kepadatan penduduk mencapai 374 jiwa/Km² pada tahun 2019. Berdasarkan perhitungan Indeks Desa Membangun 2019 (IDM)1 yang dikeluarkan oleh kementrian desa dengan nilai total 0,5987 maka desa Balaroa Pewunu dapat dikategorikan sebagai desa tertinggal atau bisa disebut sebagai desa pra-madya, Desa yang memiliki potensi sumber daya sosial, ekonomi, dan ekologi tetapi belum, atau kurang mengelolanya dalam upaya peningkatan kesejahteraan masyarakat Desa, kualitas hidup manusia serta mengalami kemiskinan dalam berbagai bentuknya. Seperti pada umumnya desa di Dolo Barat, komoditas tanaman padi sawah selain sebagai pemenuhan kebutuhan pangan juga merupakan tumpuhan petani dalam menambah pendapatan keluarga, varitas padi sawah (irigasi) yang dibudidayakan petani antara lain 1http://idm.kemendesa.go.id/idm_data?id_prov=72&id_kabupaten=7210&id_kecamatan=721011&id_desa=7210112011&tahu n=2019, Rumusan IDM berdasarkan Peraturan Menteri Desa, Pembangunan Daerah Tertinggal dan Transmigrasi No 2 tahun 2016 Tentang Indek Desa Membangun. -

Multatuli, 1860)

COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Edited by Franco Moretti: The Novel, Volume 2: Forms and Themes is published by Princeton University Press and copyrighted, © 2006, by Princeton University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher, except for reading and browsing via the World Wide Web. Users are not permitted to mount this file on any network servers. Follow links Class Use and other Permissions. For more information, send email to: [email protected] BENEDICT ANDERSON Max Havelaar (Multatuli, 1860) These were truly four anni mirabiles. In 1818 were born Ivan Turgenev and Emily Brontë, in 1819, Herman Melville and George Eliot; and in 1821, Fy odor Dostoevsky and Gustave Flaubert. Right in the middle, in 1820, came Eduard Douwes Dekker, better known by his nom de plume, Multatuli. His novel Max Havelaar, which over the past 140 years has been translated into more than forty languages and has given him a certain international rep utation, appeared in 1860. It was thus sandwiched between, on the one side, On the Eve (1860), The Mill on the Floss (1860), George Sand’s Le marquis de Villemer (1860), Great Expectations (1860–61) Adam Bede, The Confi dence Man, Madame Bovary, and Oblomov (all in 1857); and on the other, Silas Marner (1861), Fathers and Sons, Salammbo, and Les misérables (1862), War and Peace (starting in 1865), and Crime and Punishment (1866). This was the generation in which Casanova’s “world republic of letters,” subdivi sion the novel, hitherto dominated by French and British males, was first profoundly challenged from its margins: by formidable women in the Channel-linked cores and by extraordinary figures from beyond the Atlantic and across the steppe. -

C'est Grâce À Un Romancier De Hollande Que Max Havelaar Existe

Le Matin Dimanche 15 mars 2020 Acteurs 21 C’est grâce à un romancier de Hollande que Max Havelaar existe ● Max Havelaar n’est pas un pionnier du commerce équitable, mais le titre d’un livre hollandais paru en 1860. Les 200 ans de la naissance de son auteur, Multatuli, sont l’occasion de remonter aux sources du combat anticolonialiste. IVAN RADJA [email protected] Ce buste, en plein cœur d’Amsterdam, parle à tous les Hollandais et laisse sans doute de marbre l’écrasante majorité des touristes. Multatuli? Inscrivez-le aux abonnés absents de la mémoire collective européenne. Et pourtant: à chaque fois que vous achetez une livre de café, des ba- nanes, du sucre brut, du miel ou des avo- cats labellisés Max Havelaar, ou Fairtrade, c’est à lui que vous le devez. De son vrai nom Eduard Douwes Dekker (1820-1887), ce fonctionnaire hollandais parti dès l’âge de 18 ans pour les Indes néerlandaises, en Indonésie, est l’auteur du livre «Max Havelaar», publié en 1860, considéré comme le premier brûlot anti- colonialiste de la littérature. Huit ans plus tôt, «La case de l’oncle Tom», de l’écrivaine Multatuli, littérale- abolitionniste Harriet Beecher Stowe, ré- ment «J’ai beau- quisitoire contre le traitement réservé aux coup enduré». esclaves des plantations de coton du sud C’est sous ce pseu- des États-Unis, une forme de «colonia- donyme qu’Eduard lisme intérieur», avait fait grand bruit. Douwes Dekker pu- blia le roman «Max Oppression des Javanais au XIXe siècle Havelaar» en 1860. Dekker l’a-t-il lu? Probablement, bien qu’il À droite, gravure n’y ait aucune certitude sur ce point. -

Parang Ilang Sebagai Interpretasi Falsafah Alam Takambang Jadi Guru Dalam Budaya Masyarakat Iban

ASIAN PEOPLE JOURNAL 2020, VOL 3(1), 1-18 e-ISSN: 2600-8971 ASIAN PEOPLE JOURNAL, 2020, VOL 3(1), 1-18 https://doi.org/10.37231/apj.2020.3.1.118 https://journal.unisza.edu.my/apj PARANG ILANG SEBAGAI INTERPRETASI FALSAFAH ALAM TAKAMBANG JADI GURU DALAM BUDAYA MASYARAKAT IBAN (Parang Ilang As An Interpretation Of Alam Takambang Jadi Guru Philosophy In Iban’s Culture) Adilawati Asri1*, Noria Tugang1 1Fakulti Seni Gunaan dan Kreatif, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, 94300 Kota Samarahan, Sarawak, Malaysia *Corresponding author: [email protected] Received: 5 September 2019 • Accepted: 25 November 2019 • Published: 30 April 2020 Abstract This research explores the craft and creativity of the art of Ilang as an interpretation of the philosophy of ‘Being a Teacher’ in the life of the Iban community. Symbolism towards the elements of nature is often used to express various ideas and meanings about their practices, culture, and life. This research uses a qualitative approach as a whole. Data obtained through qualitative approach using observations and interviews. Overall research has found that the human mind is made up of natural properties. Humans learn from nature and create the aesthetics they learn from it. Nature is made as a 'teacher', a human mind built from nature. This means that the developing world teaches humans to think creatively and to create something using natural resources, such as parang Ilang. Every event that happens around human life may not be separated from nature. The Iban people live in a natural environment. For them, nature is a ‘teacher’ to solve all the problems that occur in their lives. -

De Scheepsjongens Van Bontekoe

De scheepsjongens van Bontekoe Johan Fabricius bron Johan Fabricius, De scheepsjongens van Bontekoe. Leopold, Amsterdam 2003 (28ste druk) Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/fabr005sche01_01/colofon.htm © 2004 dbnl / erven Johan Fabricius binnenzijde omslag Johan Fabricius, De scheepsjongens van Bontekoe 7 Aan de Hollandse Jongens! ‘In 't Jaer ons Heeren 1618, den 28. December, ben ick, WILLEM IJSBRANTSZ. BONTEKOE van Hoorn, Tessel uytghevaeren voor schipper, met het schip ghenaemt: Nieu-Hoorn, ghemant met 206 eters, groot omtrent 550 lasten, met een Oosten-Wint...’ Zo, m'n jongens, zet het Journael in van een der eerste, kranige ‘Schippers naast God’, die met hun wakkere mannen ons gezag in Indië vestigden. Elke kajuitsjongen uit de zeventiende eeuw had, als hij ook maar een beetje lezen kon, het verhaal in zijn scheepskist liggen bij z'n bijbeltje en zijn onderbroeken. En Potgieter dichtte op Bontekoes reis een reeks ‘liedekes’. Bontekoe heeft geen zilvervloot veroverd en ook geen tocht naar Chatham gemaakt. Hij volbracht zijn simpele opdracht (met een notedop-zeekasteel de Kaap te omzeilen) in rustig vertrouwen op God, - als alle schippers uit onze Gouden Eeuw, die op hun avontuurlijke zwerftochten naar het onbekende land door oud en jong werden nageoogd en benijd om de heldhaftige taak die ze gingen vervullen. En Willem IJsbrantsz. Bontekoe zou waarschijnlijk evenals zijn kameraden geheel in de vergetelheid zijn geraakt, wanneer hij niet een reis had gemaakt zó vol tegenslagen, als de geschiedenis onzer zeevaarders er wellicht geen andere telt. Maar hij was taai. Toen zijn schip op de Indische Oceaan in brand vloog, verliet hij het niet, voor hij ermee de lucht invloog. -

Fine Art & Antiques Auction

FINE ART & ANTIQUES AUCTION Tuesday 26th ofMarch Bath Ltd2019. at 10.00am Lot: 138 AT PHOENIX HOUSE Lower Bristol Road, BATH BA2 9ES Tel: (01225) 462830 Aldr-CatCover.qxp:Aldr-CatCover07 20/3/12 15:33 Page 2 Aldr-CatCover.qxp:Aldr-CatCover07 20/3/12 15:33 Page 2 BUYER’S PREMIUM AAB Buyer’suyer’s p premiumremium o off 1 20%7B.U5%Y ofEo fRthet’hSe hammerPhRamEmMeI rUpricepMrice isi spayablepayable ata tallal lsales.sales. A ThisTBhuiyse premiumpr’rsepmreiummiu iisms subjectsoufb1je7c.t5 %ttoo othethf et hadditionaeddhiatmiomn eoforf pVATVrAiTce ataits thetphaey standardsatbalnedaatrdal rate.lrastael.es. This premium is subject to the addition of VAT at the standard rate. CONDITIONS OF SALE 1. Every effort has been madCeOtoNeDnsIuTrIeOthNe SacOcuFraScyAoLfEthe description of each lot but 1. Ethveesrey wefhfoertthherasmbaedeen omraaldlye toor einstuhre tchaetaaloccgureacayreoefxtphreesdseioscnrsipotifoonpoinf ieoanchanlodt nbuot trhepersesewnhtaetihoenrsmoafdfeacot.raNlloy eomr pinloythee ocafttahloegAuuecatiroeneexeprsrehssaisonans yofauotphinorioitny taondmnakoet arenpyrerseepnrteasteinotnastiofnfoafctf.acNtoanemd pthloeyaeuecotifotnheeerAs udcitsicolaniemersonhabsehanalyf oauf tthhoerViteyntdoomr aankde athneymreseplrveessenretsaptioonnsiobfilfiatyctfoanr dautthheenautictiitoy,naegeers, odriisgcilnaimandoncobnedhiatlifonofatnhde fVoernadcocur raancdy othfemmesaesluvreesmreesnptoonrsiwbieligtyhtfoorfaauntyhelonttiocritlyo,tasg. e, origin and condition and for accuracy oPfumrcehaassuerresmpeunrtcohrasweeiaglhl tlootfsavniyewloetdorwliotths.