Scraps of Hope in Banda Aceh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SATURDAY, AUGUST 28, 2021 at 10:00 AM

www.reddingauction.com 1085 Table Rock Road, Gettysburg, PA PH: 717-334-6941 Pennsylvania's Largest No Buyers Premium Gun Auction Service Your Professional FireArms Specialists With 127+ Combined Years of Experience Striving to Put Our Clients First & Achieving Highest Prices Realized as Possible! NO RESERVE – NO BUYERS PREMIUM If You Are Interested in Selling Your Items in an Upcoming Auction, Email [email protected] or Call 717- 334-6941 to Speak to Someone Personally. We Are Consistently Bringing Higher Prices Realized Than Other Local Auction Services Due to Not Employing a Buyer’s Premium (Buyer’s Penalty). Also, We Consistently Market Our Sales Nationally with Actual Content For Longer Periods of Time Than Other Auction Services. SATURDAY, AUGUST 28, 2021 at 10:00 AM PLEASE NOTE: -- THIS IS YOUR ITEMIZED LISTING FOR THIS PARTICULAR AUCTION PLEASE BRING IT WITH YOU WHEN ATTENDING Abbreviation Key for Ammo Lots: NIB – New in Box WTOC – Wrapped at Time of Cataloging (RAS Did Not Unwrap the Lots With This Designation in Order to Verify the Correctness & Round Count. We depend on our consignor’s honesty and integrity when describing sealed boxes. RAS Will Offer No Warranties or No Guarantees Regarding Count or the Contents Inside of These Boxes) Any firearms with a “R” after the lot number means it is a registrable firearm. Any firearms without the “R” is an antique & Mfg. Pre-1898 meaning No registration is required. Lot #: 1. Winchester – No. W-600 Caged Copper Room Heater w/Cord – 12½” Wide 16” High w/Gray Base (Excellent Label) 2. Winchester-Western – “Sporting Arms & Ammunition” 16” Hexagon Shaped Wall Clock – Mfg. -

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality: a Study of Majlis Dhikr Groups

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Arif Zamhari THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E P R E S S E P R E S S Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/islamic_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Zamhari, Arif. Title: Rituals of Islamic spirituality: a study of Majlis Dhikr groups in East Java / Arif Zamhari. ISBN: 9781921666247 (pbk) 9781921666254 (pdf) Series: Islam in Southeast Asia. Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Islam--Rituals. Islam Doctrines. Islamic sects--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Sufism--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Dewey Number: 297.359598 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changesthat the author may have decided to undertake. -

Pelaksanaan Syariat Islam Di Aceh Sebagai Otonomi Khusus Yang Simetris

Prof. Dr. Al Yasa` Abubakar, MA. PELAKSANAAN Syariat Islam DI ACEH SEBAGAI OTONOMI KHUSUS YANG ASIMETRIS (Sejarah Dan Perjuangan) Dinas Syariat Islam Aceh Tahun 2020 PELAKSANAAN SYARIAT ISLAM DI ACEH SEBAGAI OTONOMI KHUSUS YANG ASIMETRIS (SEJARAH DAN PERJUANGAN) Prof. Dr. Al Yasa` Abubakar, MA. Editor : DR. EMK. Alidar, S.Ag., M.Hum Tata Letak Isi : Muhammad Sufri Desain Cover : Syahreza Diterbitkan oleh: Dinas Syariat Islam Aceh Jln T. Nyak Arief No.221, Jeulingke. Banda Aceh Email : [email protected] Telp : (0651) 7551313 Fax : (0651) 7551312, (0651) 7551314 Bekerjasama dengan Percetakan: CV. Rumoh Cetak Jalan Utama Rukoh, Syiahkuala, Banda Aceh Email: [email protected] | Hp: 08116888292 Dinas Syariat Islam Aceh viii + 224 hlm. 14 x 21 cm. ISBN. 978-602-58950-5-0 Pengantar penulis BISMILLAHIRRAHMANIRRAHIM Puji dan syukur penulis persembahkan ke hadirat Allah Swt. atas segala karunia dan rahmat yang dilimpahkan- Nya, shalawat dan salam penulis haturkan ke pangkuan Nabi Muhammad Rasul penutup dan penghulu para nabi--yang diutus sebagai rahmat untuk semesta alam, serta kepada semua keluarga dan Sahabat beliau. Dengan izin serta karunia Allah Swt. penulisn buku dengn judul PELAKSANAAN SYARIAT ISLAM DI ACEH SEBAGAI OTONOMI KHUSUS YANG ASIMETRIS (Sejarah Dan Perjuangan) telah dapat penulis rampungkan dan selesaikan penulisannya. Untuk itu penulis mengucapkan terima kasih yang tulus kepada semua pihak yang telah membantu penulis, dengan caranya masing-masing, sehingga tulisan ini dapat penulis rampungkan. Terutama sekali kepada para mahasiswa, para peneliti dan para peminat yang sering mengajukan pertanyaan yang tajam dan menggelitik, kritik yang pedas, atau pujian berlebihan yang tidak menggembirakan, baik mengenai isi buku yang penulis tulis, atau juga mengenai kebijakan, dan kenyataan nyata pelaksanaan qanun- qanun yang berkaitan dengna syariat Islam selama ini. -

269 Abdul Aziz Angkat 17 Abdul Qadir Baloch, Lieutenant General 102–3

Index Abdul Aziz Angkat 17 Turkmenistan and 88 Abdul Qadir Baloch, Lieutenant US and 83, 99, 143–4, 195, General 102–3 252, 253, 256 Abeywardana, Lakshman Yapa 172 Uyghurs and 194, 196 Abu Ghraib 119 Zaranj–Delarum link highway 95 Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) 251, 260 Africa 5, 244 Abuza, Z. 43, 44 Ahmad Humam 24 Aceh 15–16, 17, 31–2 Aimols 123 armed resistance and 27 Akbar Khan Bugti, Nawab 103, 104 independence sentiment and 28 Akhtar Mengal, Sardar 103, 104 as Military Operation Zone Akkaripattu- Oluvil area 165 (DOM) 20, 21 Aksu disturbances 193 peace process and Thailand 54 Albania 194 secessionism 18–25 Algeria Aceh Legislative Council 24 colonial brutality and 245 Aceh Monitoring Mission (AMM) 24 radicalization in 264 Aceh Referendum Information Centre Ali Jan Orakzai, Lieutenant General 103 (SIRA) 22, 24 Al Jazeera 44 Acheh- Sumatra National Liberation All Manipur Social Reformation, women Front (ASNLF) 19 protesters of 126–7 Aceh Transition Committee (Komite All Party Committee on Development Peralihan Aceh) (KPA) 24 and Reconciliation ‘act of free choice’, 1969 Papuan (Sri Lanka) 174, 176 ‘plebiscite’ 27 All Party Representative Committee Adivasi Cobra Force 131 (APRC), Sri Lanka 170–1 adivasis (original inhabitants) 131, All- Assam Students’ Union (AASU) 132 132–3 All- Bodo Students’ Union–Bodo Afghanistan 1–2, 74, 199 Peoples’ Action Committee Balochistan and 83, 100 (ABSU–BPAC) 128–9, 130 Central Asian republics and 85 Bansbari conference 129 China and 183–4, 189, 198 Langhin Tinali conference 130 India and 143 al- Qaeda 99, 143, -

TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 405 265 SO 026 916 TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995. Participants' Reports. INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC.; Malaysian-American Commission on Educational Exchange, Kuala Lumpur. PUB DATE 95 NOTE 321p.; Some images will not reproduce clearly. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Reports Descriptive (141) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Asian History; *Asian Studies; Cultural Background; Culture; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Foreign Culture; *Global Education; Human Geography; Instructional Materials; *Non Western Civilization; Social Studies; *World Geography; *World History IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Malaysia ABSTRACT These reports and lesson plans were developed by teachers and coordinators who traveled to Malaysia during the summer of 1995 as part of the U.S. Department of Education's Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program. Sections of the report include:(1) "Gender and Economics: Malaysia" (Mary C. Furlong);(2) "Malaysia: An Integrated, Interdisciplinary Social Studies Unit for Middle School/High School Students" (Nancy K. Hof);(3) "Malaysian Adventure: The Cultural Diversity of Malaysia" (Genevieve M. Homiller);(4) "Celebrating Cultural Diversity: The Traditional Malay Marriage Ritual" (Dorene H. James);(5) "An Introduction of Malaysia: A Mini-unit for Sixth Graders" (John F. Kennedy); (6) "Malaysia: An Interdisciplinary Unit in English Literature and Social Studies" (Carol M. Krause);(7) "Malaysia and the Challenge of Development by the Year 2020" (Neale McGoldrick);(8) "The Iban: From Sea Pirates to Dwellers of the Rain Forest" (Margaret E. Oriol);(9) "Vision 2020" (Louis R. Price);(10) "Sarawak for Sale: A Simulation of Environmental Decision Making in Malaysia" (Kathleen L. -

Small Replacement Parts Case, Empty A.6144 Old Ballpoint Pen with Head for Classic 0.62

2008 Item No. Page Item No. Page 0.23 00 – 5.01 01 – 1 22 0.61 63 5.09 33 5.10 10 – 0.62 00 – 2 – 23 – 5.11 93 0.63 86 3 24a Blister 0.64 03 – 5.12 32 – 4 25 0.70 52 5.15 83 0.80 00 – 5.16 30 – 26 – 4 0.82 41 5.47 23 29 0.71 00 – 5.49 03 – 30a – 5 0.73 33 5.49 33 30b 0.83 53 – 6 – 5.51 00 – 32 – 0.90 93 7 5.80 03 34 1.34 05 – 9 – 6.11 03 – 36 – 1.77 75 11 6.67 00 37 1.78 04 – 6.71 11 – 38 – 11a 1.88 02 6.87 13 38a 1.90 10 – 7.60 30 – 41 – 13 1.99 00 7.73 50 43 Ecoline 7.71 13 – 43a – 2.21 02 – 14 7.74 33 43b 3.91 40 2.10 12 – 14a – 7.80 03 – 44 – 3.03 39 14c 7.90 35 44a CH-6438 Ibach-Schwyz Switzerland 8.09 04 – 46 – Phone +41 (0)41 81 81 211 4.02 62 – 16 – Fax +41 (0)41 81 81 511 8.21 16 47b 4.43 33 18b www.victorinox.com Promotional P1 [email protected] material A VICTORINOX - MultiTools High in the picturesque Swiss Alps, the fourth generation of the Elsener family continues the tradition of Multi Tools and quality cutlery started by Charles and Victoria Elsener in 1884. In 1891 they obtained the first contract to supply the Swiss Army with a sturdy «Soldier’s Knife». -

Understanding Intangible Culture Heritage Preservation Via Analyzing Inhabitants' Garments of Early 19Th Century in Weld Quay

sustainability Article Understanding Intangible Culture Heritage Preservation via Analyzing Inhabitants’ Garments of Early 19th Century in Weld Quay, Malaysia Chen Kim Lim 1,*, Minhaz Farid Ahmed 1 , Mazlin Bin Mokhtar 1, Kian Lam Tan 2, Muhammad Zaffwan Idris 3 and Yi Chee Chan 3 1 Institute for Environment & Development (LESTARI), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi 43600, Malaysia; [email protected] (M.F.A.); [email protected] (M.B.M.) 2 School of Digital Technology, Wawasan Open University, 54, Jalan Sultan Ahmad Shah, George Town 10050, Malaysia; [email protected] 3 Faculty of Art, Computing & Creative Industry, Sultan Idris Education University, Tanjong Malim 35900, Malaysia; [email protected] (M.Z.I.); [email protected] (Y.C.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This qualitative study describes the procedures undertaken to explore the Intangible Culture Heritage (ICH) preservation, especially focusing on the inhabitants’ garments of different ethnic groups in Weld Quay, Penang, which was a multi-cultural trading port during the 19th century in Malaysia. Social life and occupational activities of the different ethnic groups formed the two main spines of how different the inhabitants’ garments would be. This study developed and demonstrated a step-by-step conceptual framework of narrative analysis. Therefore, the procedures used in this study are adequate to serve as a guide for novice researchers who are interested in undertaking Citation: Lim, C.K.; Ahmed, M.F.; a narrative analysis study. Hence, the investigation of the material culture has been exemplified Mokhtar, M.B.; Tan, K.L.; Idris, M.Z.; by proposing a novel conceptual framework of narrative analysis. -

Analisis Kebijakan Introduksi Spesies Ikan Asing Di Perairan Umum Daratan Provinsi Aceh

J. Kebijakan Sosial Ekonomi Kelautan dan Perikanan Vol. 1 No. 1 Tahun 2011 ANALISIS KEBIJAKAN INTRODUKSI SPESIES IKAN ASING DI PERAIRAN UMUM DARATAN PROVINSI ACEH Z. A. Muchlisin Jurusan Budidaya Perairan, Koordinatorat Kelautan dan Perikanan, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh 23111; Tsunami and Disaster Mitigation Research Center (TDMRC), Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh Email: [email protected] Diterima 1 September 2011 - Disetujui 11 Desember 2011 ABSTRAK Provinsi Aceh memiliki potensi perikanan perairan umum daratan yang besar dengan berbagai spesies lokal. Potensi ini belum sepenuhnya dimanfaatkan baik untuk perikanan tangkap maupun budidaya. Di sisi lain, tekanan terhadap perairan umum daratan semakin meningkat terutama disebabkan oleh kerusakan lingkungan, pencemaran, pemanasan global dan introduksi spesies ikan asing yang mengancam komunitas ikan lokal. Introduksi spesies ikan asing menjadi isu penting, baik di tataran global maupun lokal. Kajian ini bertujuan untuk menganalisis dan mengadvokasi awal kebijakan introduksi spesies ikan asing di Provinsi Aceh. Untuk memberikan gambaran yang lebih jelas, kajian ini menggunakan studi kasus introduksi spesies ikan asing di Danau Laut Tawar. Kajian ini menggunakan metode analisis deskriptif-eksploratif dan studi literatur sebagai basis kebijakan introduksi spesies ikan asing yang perlu mendapatkan perhatian. Hasil kajian menunjukkan sebanyak sembilan spesies ikan asing telah ada diperairan Aceh. Dari jumlah tersebut, tujuh spesies diantaranya telah hadir di Danau Laut Tawar. Saat ini Pemerintah Provinsi Aceh belum memiliki kebijakan untuk mengatur introduksi spesies ikan asing ke perairan Aceh. Hal ini dapat menyebabkan ancaman terhadap spesies ikan lokal. Karena itu kebijakan berupa peraturan daerah yang mengatur hal tersebut sangat diperlukan. Kata Kunci: endemik, konservasi, depik dan Danau Laut Tawar Abstract: Policy Analysis of Introducing Alien Species of Fish in Inland Waters of Aceh Province. -

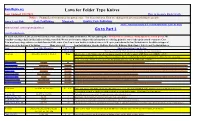

Laws for Folder Type Knives Go to Part 1

KnifeRights.org Laws for Folder Type Knives Last Updated 1/12/2021 How to measure blade length. Notice: Finding Local Ordinances has gotten easier. Try these four sites. They are adding local government listing frequently. Amer. Legal Pub. Code Publlishing Municode Quality Code Publishing AKTI American Knife & Tool Institute Knife Laws by State Admins E-Mail: [email protected] Go to Part 1 https://handgunlaw.us In many states Knife Laws are not well defined. Some states say very little about knives. We have put together information on carrying a folding type knife in your pocket. We consider carrying a knife in this fashion as being concealed. We are not attorneys and post this information as a starting point for you to take up the search even more. Case Law may have a huge influence on knife laws in all the states. Case Law is even harder to find references to. It up to you to know the law. Definitions for the different types of knives are at the bottom of the listing. Many states still ban Switchblades, Gravity, Ballistic, Butterfly, Balisong, Dirk, Gimlet, Stiletto and Toothpick Knives. State Law Title/Chapt/Sec Legal Yes/No Short description from the law. Folder/Length Wording edited to fit. Click on state or city name for more information Montana 45-8-316, 45-8-317, 45-8-3 None Effective Oct. 1, 2017 Knife concealed no longer considered a deadly weapon per MT Statue as per HB251 (2017) Local governments may not enact or enforce an ordinance, rule, or regulation that restricts or prohibits the ownership, use, possession or sale of any type of knife that is not specifically prohibited by state law. -

Religious Freedom Implications of Sharia Implementation in Aceh, Indonesia Asma T

University of St. Thomas Law Journal Volume 7 Article 8 Issue 3 Spring 2010 2010 Religious Freedom Implications of Sharia Implementation in Aceh, Indonesia Asma T. Uddin Bluebook Citation Asma T. Uddin, Religious Freedom Implications of Sharia Implementation in Aceh, Indonesia, 7 U. St. Thomas L.J. 603 (2010). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UST Research Online and the University of St. Thomas Law Journal. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE RELIGIOUS FREEDOM IMPLICATIONS OF SHARIA IMPLEMENTATION IN ACEH, INDONESIA ASMA T. UDDIN* INTRODUCTION On Monday, September 14, 2009, the provincial legislature in Aceh, Indonesia passed Sharia regulations imposing stringent criminal punish- ments for various sexual offenses, such as adultery and fornication.1 Sharia, literally meaning “way to a watering place,” is a set of divine principles that regulate a Muslim’s relationship with God and man by providing social, moral, religious, and legal guidance. It is implemented through fiqh, or Is- lamic jurisprudence, which is the science of interpreting religious texts in order to deduce legal rulings. The Acehnese Sharia regulations are the latest manifestations of a process of formal implementation of Sharia that began in 2002 in Aceh.2 Given the gravity of the associated punishments, the reg- ulations have caught national and international attention, with human rights activists across the world decrying the severity of the corporal punishments imposed by the regulations. Much less frequently scrutinized are the regula- tions’ implications for other human rights—such as religious freedom. This paper analyzes these regulations’ religious freedom implications for both Muslims and non-Muslims. -

The Syiah Turmoil in a Sharia Soil: an Anthropological Study of Hidden Syiah Minority Entity in Contemporary Aceh

International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE) ISSN: 2277-3878, Volume-7, Issue-6S5, April 2019 The Syiah Turmoil in a Sharia Soil: An Anthropological Study of Hidden Syiah Minority Entity in Contemporary Aceh Al Chaidar Abdurrahman Puteh, Abidin Nurdin, T. Nazaruddin , Alfian Lukman Abstract: Syiah had ever been a major Islamic Researches on the history of Syiah in Indonesia - and denomination in Aceh for centuries. This research is not only especially in Aceh -has been done by Hilmy Bakar about how much classical Sharia rules can be a reference to Almascaty (2013) and Fakhriati (2014) and Rabbani (2013) resolve political problems of majority and minority division, but also Dhuhri (2016). Previously, a similar study also also to examine the power of sharia in protecting and concerns the history that comes first in reference to the marginalizing Syiah. Based mainly on classical Snouck Hurgronje ethnography, this study elaborate the the former history of Syiah and its spaces investigated by Thabathaba'i sharia as a living law in old Aceh and comparing it with recent and Husayn (1989), Azmi (1989), Abdul Hadi (2002), and legal pluralism of Aceh nowadays. With a spectacular growing T. Iskandar (2011). Almascaty's study looked more at of traditional Dayah (conservative Sunnism) in present politics, Persian civilization and its influence on customs in Aceh and the transnational Salafi Wahabism intrusion into Aceh, the [1]. Similarly, Wan Hussein Azmi concluded that in the position of Syiah is at the most tip of the edge in society. 10th century AD migration of the most Persians to the Achenese Syiah are now facing hardest situation in this Syafii- archipelago Leran, Gresik, Siak (Inderapura, Riau), and to dominated land and hardened with the rage of Wahabism. -

Separatism in Indonesia Ñ the Cases of Aceh and Papua Ñ

SUMMARY Separatism in Indonesia Ñ The Cases of Aceh and Papua Ñ Osamu INOUE If in the future disintegration does happen in the Republic of Indonesia, the states most likely to separate from Indonesia are Aceh (the most western province) and Papua (the most eastern province). Such development has come under the calculation of the central government since the downfall of the Soeharto regime. The government for some time has been making preparations to formulate autonomy plans for the two states in an effort to prevent the disintegration from happening. But despite the governmentÕs endeavoer, the Aceh and Papua communities seem still discontented. This can be seen from the fact that they still keep on demanding a referendum. As a democratic country, the government cannot turn down such demands, and one day will have to accept the demand for a referendum to let the people of the two provinces vote for their futures. Certainly the way to referendums is not going to be smooth, as there are a number of politicians and security personnel who are worried that such a move will become a precedent for other provinces that might seek to ask for separation. The central government does not want to see Indonesia break up into many small countries. Nevertheless, according to my view, the possibility of such a national split is not high, as Aceh and Papua have a different historical background from that of the other provinces. Concerning Aceh, first, if we look back on history, the Aceh community never surrendered authority to the Dutch government. Therefore, it can be regarded that Aceh joined the Republic of Indonesia in 1945 when Indonesia proclaimed independence from the Dutch government.