Ernest Starling and 'Hormones': an Historical Commentary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bloomsbury Scientists Ii Iii

i Bloomsbury Scientists ii iii Bloomsbury Scientists Science and Art in the Wake of Darwin Michael Boulter iv First published in 2017 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.ucl.ac.uk/ ucl- press Text © Michael Boulter, 2017 Images courtesy of Michael Boulter, 2017 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial Non-derivative 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non-commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Michael Boulter, Bloomsbury Scientists. London, UCL Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787350045 Further details about Creative Commons licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 006- 9 (hbk) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 005- 2 (pbk) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 004- 5 (PDF) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 007- 6 (epub) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 008- 3 (mobi) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 009- 0 (html) DOI: https:// doi.org/ 10.14324/ 111.9781787350045 v In memory of W. G. Chaloner FRS, 1928– 2016, lecturer in palaeobotany at UCL, 1956– 72 vi vii Acknowledgements My old writing style was strongly controlled by the measured precision of my scientific discipline, evolutionary biology. It was a habit that I tried to break while working on this project, with its speculations and opinions, let alone dubious data. But my old practices of scientific rigour intentionally stopped personalities and feeling showing through. -

Back Matter (PDF)

INDEX to VOL. CII. (A) Absorption bands, wave-lengtli measurement of (Hartridge), 575. Address of the President, 1922, 373. a- and /3-rays, theory of scattering (Jeans), 437. a-particle passing through matter, changes in charge of (Henderson), 496. «-ray, loss of energy of, in passage through matter (Kapitza), 48. a-ray photographs, analysis of (Blackett), 294. Aluminium crystal, distortion during tensile test (Taylor and Elam), 643. Argon, ionisation by electron collisions (Horton and Davies), 131. Armstrong (E. F.) and Hilditch (T. P.) A Study of Catalytic Action at Solid Surfaces.— Part VIII, 21 ; Part IX, 27. Astbury (W. T.) The Crystalline Structure and Properties of Tartaric Acid, 506. Atmosphere, outer, and theory of meteors (Lindemann and Dobson), 411. Atmospheric disturbances, directional observations of (Watt), 460. Atomic hydrogen, incandescence in (Wood), 1. Backliurst (I.) Variation of the Intensity of Reflected X-radiation with the Tem perature of the Crystal, 340. Bakerian Lecture (Taylor and Elam), 643. Berry (A.) and Swain (L. M.) On the Steady Motion of a Cylinder through Infinite Viscous Fluid, 766. /3-rays, scattering of (Wilson), 9. Blackett (P. M. S.) On the Analysis of u-Ray Photographs, 294. Brodetsky (S.) The Line of Action of the Resultant Pressure in Discontinuous Fluid Motion, 361 ; ----- Discontinuous Fluid Motion past Circular and Elliptic Cylinders 542. Cale (F. M.) See McLennan and Cale. Campbell (J. H. P.) See Whytlaw-Gray. Carbon arc ultra-violet spectrum (Simeon), 484. Catalytic Action (Armstrong and Hilditch), 21, 27. Christie (Sir W.) Obituary notice of, xi. Clark (M. L.) See McLennan and Clark. Colloidal behaviour, theory of (Hill), 705. -

Historical Development and Ethical Considerations of Vivisectionist and Antivivisectionist Movement*

JAHR Vol. 3 No. 6 2012 UDK 179.4 Invited review Bruno Atalić* Historical development and ethical considerations of vivisectionist and antivivisectionist movement* Abstract This review presents historical development and ethical considerations of vivisectionist and antivivisectionist movement. In this respect it shows that both movements were not just characteristic for the past one hundred years, but that they were present since the beginning of medical development. It, thus, re-evaluates the accepted notions of the earlier authors. On this track it suggests that neither movement was victorious in the end, as it could be seen from the current regulations of animal experiments. Finally, it puts both movements into a wider context by examining the connection between antivivisectionism and utilitarianism on the one hand, and vivisectionism and experimentalism on the other hand. Key words: vivisectionism; antivivisectionism; bioethics; utilitarianism; experimentalism Introduction This review will try to present historical development and ethical considerations of vivisectionist and antivivisectionist movement in order to re-evaluate the accepted notions of the earlier authors. Firstly, it evaluates the Lansbury's notion that anti- vivisectionism was characteristic for the North European Protestant countries like England and Sweden, while vivisectionism was characteristic for the South Europe- an Catholic countries like France and Italy.1 Then, it proceeds to the Mason's over- 1 Lansbury C. The Old Brown Dog – Women, Workers, and Vivisection -

British Medical Journal London Saturday June 4 1955

BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL LONDON SATURDAY JUNE 4 1955 SIR HENRY DALE'S CONTRIBUTION TO PHYSIOLOGY* BY LORD ADRIAN, O.M., M1D., F.R.C.P., P.R.S. Master of Trinity College, Cambridge There is no one who could write adequately about the pharmacologists, organic chemists, and clinicians on whole field of Sir Henry Dale's scientific work, but no their own ground; he could use their methods as well one can write about any part of it without feeling that as speak their language, and could see the bearing of a in this case our conventional labels and signposts are a discovery in one department on the advance of another. mistake. Certainly he began in the early years of this But the marvel has been that he can still do so in spite century with work which would then have ranked as of all the expansion of medical science in this half- physiology, and he is now century, the entry of bio- regarded by physiologists _ chemistry and physical in every part of the world chemistry, the multiplica- with the affectionate vener- tion of hormones and vita- ation we reserve for our mins and enzymes, and the greatest masters. But his proliferation of technical first researches could be terms and methods of claimed now by the anato- every sort. The great mists, his major contribu- triumphs of chemotherapy tions have- enriched the been in the field O | 1have fields of pharmacology which he knows best, but and therapeutics, and, as it is difficult to think of head of the National Insti- any in which he cannot tute for Medical Research still hold his own. -

What's in a Name? Henry Dale and Adrenaline, 1906

Medical History, 1995, 39: 459-476 What's in a Name? Henry Dale and Adrenaline, 1906 E M TANSEY* By the beginning of the twentieth century the use of widespread advertising, trade names, and specialized marketing techniques was a distinctive feature of the commercial world. These attributes were well developed in the trade in medicines, a field that ranged from quack cures and secret remedies through proprietary brands to "ethical pharmacy".1 The British pharmaceutical firm, Burroughs, Wellcome & Co. had, by that time, achieved considerable success in promoting itself as an ethical company guided by scientific principles and remote from the quackery and chicanery of pill peddlers and nostrum- mongers. A component of that ethical behaviour was the maintenance of their own production and advertising standards and the proper recognition of others' commercial rights. In the final decade of the nineteenth century Burroughs, Wellcome & Co. had established quasi-independent laboratories, the Wellcome Physiological Research Laboratories (WPRL), in which physiologists and pharmacologists were employed to undertake basic research not directly or necessarily associated with the company's commercial enterprises. One such scientist was the future Nobel Laureate Henry Dale, who in 1906 wished to publish a paper in which the word "adrenaline" appeared.2 This was then the commonly accepted term, within Britain's physiological community, for the active principle of the suprarenal gland. However, the word "Adrenalin" was a registered trademark of the American pharmaceutical firm Parke, Davis & Co., and Dale's intended use was forbidden by Henry Wellcome. Dale and his colleagues refused to accept this injunction, and the ensuing debates raised important issues within the Wellcome *E M Tansey, BSc, PhD, PhD, Wellcome Institute Professor W F Bynum, Dr S P Lock, Professor J for the History of Medicine, 183 Euston Road, Parascandola and Professor M Weatherall for their London NW1 2BE. -

Protection Against Dog Distemper and Dogs Protection Bills: the Medical Research Council and Anti-Vivisectionist Protest, 1911-1933

Medical Historv, 1994, 38: 1-26. PROTECTION AGAINST DOG DISTEMPER AND DOGS PROTECTION BILLS: THE MEDICAL RESEARCH COUNCIL AND ANTI-VIVISECTIONIST PROTEST, 1911-1933 by E. M. TANSEY * The National Insurance Act of 1911 provided, by creating the Medical Research Committee, explicit government support for experimental, scientific medicine. This official gesture was made against a background of concern about some of the methods of scientific medicine, especially the use of living animals in medical research. Organized protests against animal experiments had gathered strength during the middle of the nineteenth century and resulted in the establishment of a Royal Commission to enquire into the practice of subjecting animals to experiments. The recommendations of that Commission led to the passing of the 1876 Cruelty to Animals Act, which governed all experiments calculated to give pain, and carried out on vertebrates. This paper will extend the examination of laboratory science and laboratory animals into a later period, the first decades of the twentieth century. It will focus on the use of one particular animal, the dog, in one specific laboratory, the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) in London, and will examine three related themes: the use and justification of the dog in experimental laboratory research into canine distemper at the Institute from its establishment in 1913 until the mid-1930s; this will be set against the protests of anti-vivisectionist groups and their use of the dog as a motif of animal suffering; and the moves by both opponents and proponents of animal experimentation to promote their views and to influence public opinion and members of the legislature. -

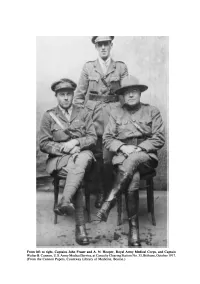

From Left to Right, Captains John Fraser and A. N. Hooper, Royal Army Medical Corps, and Captain Walter B. Cannon, U.S. Army

.1-00 .i., ik "N --'. ... ..l j From left to right, Captains John Fraser and A. N. Hooper, Royal Army Medical Corps, and Captain Walter B. Cannon, U.S. Army Medical Service, at Casualty Clearing Station No. 33, Bethune, October 1917. (From the Cannon Papers, Countway Library of Medicine, Boston.) Medical History, 1991, 35: 217-249. WALTER B. CANNON AND THE MYSTERY OF SHOCK: A STUDY OF ANGLO-AMERICAN CO-OPERATION IN WORLD WAR I by SAUL BENISON, A. CLIFFORD BARGER, and ELIN L. WOLFE * The hospital is on a gentle slope, whence one can see far out along the avenue down which we have come. It is all gay and golden. The earth lies there, still and smooth and secure; even fields are to be seen, little, brown, tilled strips, right close by the hospital. And when the wind blows away the stench ofblood and ofgangrene, one can smell the pungent ploughed earth. The distance is blue and everywhere peaceful, for from here the view is away from the Front. -Erich Maria Remarque, Prologue to Der Weg Zuruck (The Road Back), 1931 The autumn of 1914 marked the beginning of an extraordinary transformation of the plains of northern France and Flanders. Fields where farmers had for centuries ploughed with horses, laid down seed, and set out livestock to graze in an effort to sustain life, in a relatively briefperiod oftime became a maiming and killing ground for British, French and German armies. At first, combatants on both sides believed the conflict would be a short one, crowned by a quick victory. -

Inside Living Cancer Cells Research Advances Through Bioimaging

PN Issue 104 / Autumn 2016 Physiology News Inside living cancer cells Research advances through bioimaging Symposium Gene Editing and Gene Regulation (with CRISPR) Tuesday 15 November 2016 Hodgkin Huxley House, 30 Farringdon Lane, London EC1R 3AW, UK Organised by Patrick Harrison, University College Cork, Ireland Stephen Hart, University College London, UK www.physoc.org/crispr The programme will include talks on CRISPR, but also showing the utility of techniques such as ZFNs and Talens. As well as editing, the use of these techniques to regulate gene expression will be explored both in the context of studying normal physiology and the mechanisms of disease. The use of the techniques in engineering cells and animals will be explored, as will techniques to deliver edited reagents and edited cells in vivo. Physiology News Editor Roger Thomas We welcome feedback on our membership magazine, or letters and suggestions for (University of Cambridge) articles for publication, including book reviews, from Physiological Society Members. Editorial Board Please email [email protected] Karen Doyle (NUI Galway) Physiology News is one of the benefits of membership of The Physiological Society, along with Rachel McCormack reduced registration rates for our high-profile events, free online access to The Physiological (University of Liverpool) Society’s leading journals, The Journal of Physiology and Experimental Physiology, and travel David Miller grants to attend scientific meetings. Membership of The Physiological Society offers you (University of Glasgow) access to the largest network of physiologists in Europe. Keith Siew (University of Cambridge) Join now to support your career in physiology: Austin Elliott Visit www.physoc.org/membership or call 0207 269 5728. -

History of Endocrinology

EDITORIAL DOI: http://doi.org/10.4038/sjdem.v6i1.7295 HISTORY OF ENDOCRINOLOGY Siyambalapitiya S1 1 Diabetes and Endocrine unit, North Colombo Teaching Hospital, Ragama. Clinical endocrinology is a branch of Medicine that deals by himself. Later, the demonstration of blood glucose with the endocrine glands, the secreted hormones and lowering property of pancreatic dog extract by Von their metabolic effects. Hormones act on almost every Mering and Menkoski led to the discovery of insulin organ and cell type in the body and there are disorders during the early part of 20th century. However, the first that are entirely or largely related abnormalities of described hormone (1902) was a result of efforts by Sir hormone production. Type I diabetes and William Bayliss (1860-1924) and Ernest Starling (1866- hypothyroidism are such examples that entirely related 1927). In response to the delivery of acidic chyme from to abnormalities of hormones. However, there are so the stomach to the intestine, endocrine cells of the many other disorders such as osteoporosis and infertility, duodenum release secretin (an internal secretion) into the which are related to hormone dysfunction. bloodstream, which is responsible for the stimulation of exocrine pancreas to secrete bicarbonate to neutralize acid coming from the stomach. Secretin was the first History of endocrinology and study of hormone hormone to be identified and many more were found function dates back to 400 BC when Hippocrates and later. Although we have a substantial knowledge Galen introduced the concept of Humoral Hypothesis regarding these molecules, a lot of research is being where they describe as the four humors (body fluids) carried out to understand more about these substances. -

Five ENDOCRINOLOGY

Five ENDOCRINOLOGY 101 The doctor who sits at the bedside of a rat Asks real questions, as befits The place, like where did that potassium go, not what Do you think of Willie Mays or the weather? So rat and doctor may converse together. Josephine Miles “The Doctor Who Sits at the Bedside of a Rat” Since the Enlightenment, however, wonder has become a disreputable passion in workaday science, redolent of the popular, the amateurish, and the childish. Scientists now reserve expressions of wonder for their personal memoirs, not their professional publications. Katharine Park and Lorraine Daston Wonders and the Order of Nature Before going on to describe my research and academic career, I wanted to provide the reader with a short “course” in endocrinology, which I still, after all these years, think is wonderful. Let’s face it—the public, the media, and I love hormones. They do such wonderful things. For example, the sex hormones are responsible at puberty for turning on bodily sexual phenotype. A new born baby not secreting thyro- id hormone from its own thyroid will never show normal brain differentiation because crucial connections between neurons in the brain require the presence of this hormone to be completed. The mother’s thyroid hormones take care of the baby’s brain growth while the baby is still in the uterus, but after birth, the baby’s thyroid must secrete its own hormones. Unless treated before six months of age with thyroid hormone, this child will grow up severely dam- aged, what one used to call a “cretin,” with irreversible low intelligence and severe skeletal and muscular growth impairment. -

Early Developments 19 1 1- 1944

Chapter 2 The Founding of the Society: Early Developments 19 1 1- 1944 2.1 Formation of the Biochemical Club 2.2 Acquisition of the Biochemical Journal 2.3 Emergence of the Biochemical Society 2.4 Financial Position of the Society 2.5 General Developments 2.6 Honorary Members 2.7 Discussion Meetings 2.8 Proceedings 2.1 Formation of the Biochemical Club The events outlined in Chapter 1 which occurred in the first decade of this century made it clear that British biochemists needed a separate forum where they could develop their subject on a national level. The general criteria necessary for establishing a new discipline, summarized at the beginning of Chapter 1, were clearly already achieved. The time was thus ripe for the formation of a Society devoted to the furtherance of Biochemistry and, on 16 January 1911, J. A. Gardner (Fig. 2.1) and R. H. A. Plimmer (Fig. 1.2), after preliminary discussions with close colleagues, sent out invitations to fifty persons likely to attend a meeting to be held at the Institute of Physiology, UCL at 2.30 p.m. on Saturday, 2 1 January 191 1, to consider the formation of a Biochemical Society. Plimmer was evidently stung into action by an article in the press describing a new science, Biochemistry, which was making rapid progress on the Continent but was apparently unknown in Britain. The invitation, written on a postcard, read “Numerous suggestions having been made that a Biochemical Society should be formed in the Country, we shall be glad if you could make it convenient to attend a meeting at the Institute of Physiology, University College London, on Saturday 2 1 st January at 2.30 p.m. -

{PDF} Charles Darwin, the Copley Medal, and the Rise of Naturalism

CHARLES DARWIN, THE COPLEY MEDAL, AND THE RISE OF NATURALISM 1862-1864 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Marsha Driscoll | 9780205723171 | | | | | Charles Darwin, the Copley Medal, and the Rise of Naturalism 1862-1864 1st edition PDF Book In recognition of his distinguished work in the development of the quantum theory of atomic structure. In recognition of his distinguished studies of tissue transplantation and immunological tolerance. Dunn, Dann Siems, and B. Alessandro Volta. Tomas Lindahl. Thomas Henry Huxley. Andrew Huxley. Adam Sedgwick. Ways and Means, Science and Society Picture Library. John Smeaton. Each year the award alternates between the physical and biological sciences. On account of his curious Experiments and Discoveries concerning the different refrangibility of the Rays of Light, communicated to the Society. David Keilin. For his seminal work on embryonic stem cells in mice, which revolutionised the field of genetics. Derek Barton. This game is set in and involves debates within the Royal Society on whether Darwin should receive the Copley Medal, the equivalent of the Nobel Prize in its day. Frank Fenner. For his Paper communicated this present year, containing his Experiments relating to Fixed Air. Read and download Log in through your school or library. In recognition of his pioneering work on the structure of muscle and on the molecular mechanisms of muscle contraction, providing solutions to one of the great problems in physiology. James Cook. Wilhelm Eduard Weber. For his investigations on the morphology and histology of vertebrate and invertebrate animals, and for his services to biological science in general during many past years. Retrieved John Ellis.