Arguments for Creolisation in Irish English*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Past, Present, and Future of English Dialects: Quantifying Convergence, Divergence, and Dynamic Equilibrium

Language Variation and Change, 22 (2010), 69–104. © Cambridge University Press, 2010 0954-3945/10 $16.00 doi:10.1017/S0954394510000013 The past, present, and future of English dialects: Quantifying convergence, divergence, and dynamic equilibrium WARREN M AGUIRE AND A PRIL M C M AHON University of Edinburgh P AUL H EGGARTY University of Cambridge D AN D EDIU Max-Planck-Institute for Psycholinguistics ABSTRACT This article reports on research which seeks to compare and measure the similarities between phonetic transcriptions in the analysis of relationships between varieties of English. It addresses the question of whether these varieties have been converging, diverging, or maintaining equilibrium as a result of endogenous and exogenous phonetic and phonological changes. We argue that it is only possible to identify such patterns of change by the simultaneous comparison of a wide range of varieties of a language across a data set that has not been specifically selected to highlight those changes that are believed to be important. Our analysis suggests that although there has been an obvious reduction in regional variation with the loss of traditional dialects of English and Scots, there has not been any significant convergence (or divergence) of regional accents of English in recent decades, despite the rapid spread of a number of features such as TH-fronting. THE PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE OF ENGLISH DIALECTS Trudgill (1990) made a distinction between Traditional and Mainstream dialects of English. Of the Traditional dialects, he stated (p. 5) that: They are most easily found, as far as England is concerned, in the more remote and peripheral rural areas of the country, although some urban areas of northern and western England still have many Traditional Dialect speakers. -

Standard Southern British English As Referee Design in Irish Radio Advertising

Joan O’Sullivan Standard Southern British English as referee design in Irish radio advertising Abstract: The exploitation of external as opposed to local language varieties in advertising can be associated with a history of colonization, the external variety being viewed as superior to the local (Bell 1991: 145). Although “Standard English” in terms of accent was never an exonormative model for speakers in Ireland (Hickey 2012), nevertheless Ireland’s history of colonization by Britain, together with the geographical proximity and close socio-political and sociocultural connections of the two countries makes the Irish context an interesting one in which to examine this phenomenon. This study looks at how and to what extent standard British Received Pronunciation (RP), now termed Standard Southern British English (SSBE) (see Hughes et al. 2012) as opposed to Irish English varieties is exploited in radio advertising in Ireland. The study is based on a quantitative and qualitative analysis of a corpus of ads broadcast on an Irish radio station in the years 1977, 1987, 1997 and 2007. The use of SSBE in the ads is examined in terms of referee design (Bell 1984) which has been found to be a useful concept in explaining variety choice in the advertising context and in “taking the ideological temperature” of society (Vestergaard and Schroder 1985: 121). The analysis is based on Sussex’s (1989) advertisement components of Action and Comment, which relate to the genre of the discourse. Keywords: advertising, language variety, referee design, language ideology. 1 Introduction The use of language variety in the domain of advertising has received considerable attention during the past two decades (for example, Bell 1991; Lee 1992; Koslow et al. -

12 English Dialect Input to the Caribbean

12 English dialect input to the Caribbean 1 Introduction There is no doubt that in the settlement of the Caribbean area by English speakers and in the rise of varieties of English there, the question of regional British input is of central importance (Rickford 1986; Harris 1986). But equally the two other sources of specific features in anglophone varieties there, early creolisation and independent developments, have been given continued attention by scholars. Opinions are still divided on the relative weight to be accorded to these sources. The purpose of the present chapter is not to offer a description of forms of English in the Caribbean – as this would lie outside the competence of the present author, see Holm (1994) for a resum´ e–b´ ut rather to present the arguments for regional British English input as the historical source of salient features of Caribbean formsofEnglish and consider these arguments in the light of recent research into both English in this region and historical varieties in the British Isles. This is done while explicitly acknowledging the role of West African input to forms of English in this region. This case has been argued eloquently and well, since at least Alleyne (1980) whose views are shared by many creolists, e.g. John Rickford. But the aim of the present volume, and specifically of the present chapter, is to consider overseas varieties of English in the light of possible continuity of input formsofEnglish from the British Isles. This concern does not seek to downplay West African input and general processes of creolisation, which of course need to be specified in detail,1 butrather tries to put the case for English input and so complement other views already available in the field. -

APPENDIX. Philip Baker (1940-2017) Bibliography of His Publications, 1969-2017

Coversheet This is the accepted manuscript (post-print version) of the article. Contentwise, the accepted manuscript version is identical to the final published version, but there may be differences in typography and layout. How to cite this publication Please cite the final published version: Bakker, P. (2018). Obituary Philip Baker. Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages, 33(2), 231-239. DOI: 10.1075/jpcl.00014.obi Publication metadata Title: Obituary Philip Baker Author(s): Peter Bakker Journal: Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages DOI/Link: 10.1075/jpcl.00014.obi Document version: Accepted manuscript (post-print) General Rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. If the document is published under a Creative Commons license, this applies instead of the general rights. This coversheet template is made available by AU Library Version 2.0, December 2017 Obituary Philip Baker (with a bibliography of his writings, not included in the printed version). -

L Vocalisation As a Natural Phenomenon

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Essex Research Repository L Vocalisation as a Natural Phenomenon Wyn Johnson and David Britain Essex University [email protected] [email protected] 1. Introduction The sound /l/ is generally characterised in the literature as a coronal lateral approximant. This standard description holds that the sounds involves contact between the tip of the tongue and the alveolar ridge, but instead of the air being blocked at the sides of the tongue, it is also allowed to pass down the sides. In many (but not all) dialects of English /l/ has two allophones – clear /l/ ([l]), roughly as described, and dark, or velarised, /l/ ([…]) involving a secondary articulation – the retraction of the back of the tongue towards the velum. In dialects which exhibit this allophony, the clear /l/ occurs in syllable onsets and the dark /l/ in syllable rhymes (leaf [li˘f] vs. feel [fi˘…] and table [te˘b…]). The focus of this paper is the phenomenon of l-vocalisation, that is to say the vocalisation of dark /l/ in syllable rhymes 1. feel [fi˘w] table [te˘bu] but leaf [li˘f] 1 This process is widespread in the varieties of English spoken in the South-Eastern part of Britain (Bower 1973; Hardcastle & Barry 1989; Hudson and Holloway 1977; Meuter 2002, Przedlacka 2001; Spero 1996; Tollfree 1999, Trudgill 1986; Wells 1982) (indeed, it appears to be categorical in some varieties there) and which extends to many other dialects including American English (Ash 1982; Hubbell 1950; Pederson 2001); Australian English (Borowsky 2001, Borowsky and Horvath 1997, Horvath and Horvath 1997, 2001, 2002), New Zealand English (Bauer 1986, 1994; Horvath and Horvath 2001, 2002) and Falkland Island English (Sudbury 2001). -

Multicultural London English

Multicultural London English Multicultural London English Below are links to two recent newspaper articles about Multicultural London English. Text A is from The Guardian’s Education pages, first published in 2006. Text B is from The Daily Mail, first published in 2013. Text A: www.theguardian.com/education/2006/apr/12/research.highereducation Text B: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2498152/Is-end-Cockney-Hybrid- dialect-dubbed-Multicultural-London-English-sweeps-country.html Task one – the titles Looking closely at the titles of the two articles, compare how language is used to present the topic. Complete the table with examples and comments on the differences. Text B: ‘Is this the end of Text A: ‘Learn Jafaikan in two Cockney? Hybrid dialect dubbed minutes’ ‘Multicultural London English’ sweeps across the country’ Sentence functions Name used for new variety of English Lexis with negative connotations Discourse: what does each title suggest the article’s stance on MLE will be? © www.teachit.co.uk 2017 28425 Page 1 of 7 Multicultural London English Task two – lexical choices Both texts use the nickname ‘Jafaikan’. Text A mentions the term in the title and later in the body of the article: ‘One schoolteacher has used the term ‘Jafaikan’ to describe the new language, but the researchers insist on more technical terminology: ‘multicultural London English’.’ Text B states ‘It was originally nicknamed Jafaican - fake Jamaican - but scientists have now said it is a dialect that been influences [sic] by West Indian, South Asian, Cockney and Estuary English.’ 1. What is the effect of Text A’s attribution (even though it is done anonymously) for the origin of the name compared to Text B’s use of a passive sentence ‘It was originally nicknamed …’? 2. -

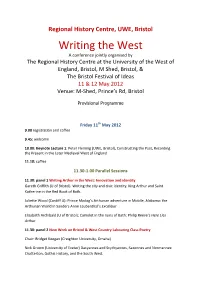

Writing the West Conference Programme

Regional History Centre, UWE, Bristol Writing the West A conference jointly organised by The Regional History Centre at the University of the West of England, Bristol, M Shed, Bristol, & The Bristol Festival of Ideas 11 & 12 May 2012 Venue: M‐Shed, Prince’s Rd, Bristol Provisional Programme Friday 11th May 2012 9.00 registration and coffee 9.45: welcome 10.00: Keynote Lecture 1: Peter Fleming (UWE, Bristol), Constructing the Past, Recording the Present in the Later Medieval West of England 11.10: coffee 11.30‐1.00 Parallel Sessions 11.30: panel 1 Writing Arthur in the West: Innovation and identity Gareth Griffith (U of Bristol): Writing the city and civic identity: King Arthur and Saint Katherine in the Red Book of Bath. Juliette Wood (Cardiff U): Prince Madog’s Arthurian adventure in Mobile, Alabama: the Arthurian World in Sanders Anne Laubenthal’s Excalibur Elizabeth Archibald (U of Bristol): Camelot in the ruins of Bath: Philip Reeve’s Here Lies Arthur 11.30: panel 2 New Work on Bristol & West Country Labouring Class Poetry Chair: Bridget Keegan (Creighton University, Omaha) Nick Groom (University of Exeter) Dacyannes and Scythyannes, Saxonnes and Normannes: Chatterton, Gothic History, and the South West. Kerri Andrews, (Strathclyde University), Ann Yearlsey, a Bristol Poet. John Goodridge (Nottingham Trent), John Gregory: sonnets, shoemaking and socialism 1.00pm Lunch 2.00‐3.30 Parallel Sessions 2.00‐3.30 panel 1: Landscape, Nature and Place Dave Postles (University of Leicester) Trickster in the Wiltshire landscape: E. M. Forster and The Longest Journey Richard Coates (UWE, Bristol) ‘Bent on emptying his note‐book in decent English’: Richard Jefferies, naturalistic observation, and English dialect. -

Index of Linguistic Items

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42359-5 — The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language 3rd Edition David Crystal Index More Information VI INDEX OF LINGUISTIC ITEMS A auto 322, 330, 493 classist 189 -eau(x) 213 auto- 138 c’mon 79 -ectomy 210 a indefinite article 234–5, 350 aye 346 co- 138 -ed form 208, 210, 216, 223, 224, 237, short vs long 327, 345, 371 cockroach 149 346, 350 verb particle 367 B colour 179 -ed vs t (verb ending) 216, 331, 493 a- 138, 335 contra- 138 -ee 210, 220 -a noun singular 212 /b-/, /-b/ (sound symbolism) 263 could 224 -een 358 noun plural 212 B/b 271, 280 counter- 138 -eer 210, 220 -a- (linking vowel) 139 babbling 483 cowboy 148 eh 319 A/a 271, 280 back of 331 crime 176 eh? 230, 362 AA (abbreviations) 131 bad 211 curate’s egg 437 elder/eldest 211 -able 210, 223 barely 230 cyber- 452 elfstedentocht 383 ableism 189 bastard 263 Elizabeth 158 -acea 210 be 224, 233, 237, 243, 367 D -elle 160 a crapella 498 inflected 21, 363 ’em 287 -ae (plural) 213 regional variation 342 /d-/, /-d/ (sound symbolism) 263 en- 138 after (aspectual) 358, 363 be- 138 D/d 271, 280–1 encyclop(a)edia 497 -age 210, 220 be about to 236 da 367 encyclopediathon 143 ageist 189 been 367 danfo 495 -ene 160 agri- 139 be going to 96, 236 dare 224 -en form 21, 210, 212, -aholic 139 Berks 97 data 213 346, 461 -aid 143, 191 best 211 daviely 352 Englexit 124 ain’t 319, 498 be to 236 De- 160 -er adjective base ending 211 aitch 359 better 211 de- 138 familiarity marker 141, 210 -al 210, 220, 223 between you and I 206, 215 demi- 138 noun ending -

Bermudian English: History, Features, Social Role Luke Swartz

Bermudian English: History, Features, Social Role Luke Swartz (Final paper for Linguistics 153) Abstract Bermudian English has been long neglected in linguistic literature. After a brief introduction to the linguistic history of the Bermuda Islands, this paper examines several interesting aspects of English dialects spoken in Bermuda. First, we examine the islands’ lack of an English Creole. Next, we examine phonological features of Bermudian English and their possible origins. Finally, we close with a discussion of Bermudian dialects’ place in education and society at large. 1. Introduction Virginia Bernhard (1999: 1) notes that, just as mariners once avoided Bermuda for fear of wrecking their ships on its coral reefs, “historians of European colonization have also bypassed Bermuda.” She quotes W. F. Craven, who wrote that “the Bermudas have been largely overlooked, the significance of their history for the most part lost to sight” (xiii). Likewise, the language of the Bermudian people has been largely ignored by linguists and historians alike. Few scholars have studied Bermudian English; the last citation of any length dates to 1933. 2 Nevertheless, the Bermuda Islands present an interesting case study of English dialects, in many ways unique among such dialects in the world. Bermudian dialects of English lack a dominant creole, have interesting phonetic features, and command an ambiguous social status. 2. Background Contrary to popular belief, Bermuda is not actually part of the Caribbean. As Caribbean/Latin American Profile points out, “Often, Bermuda is placed erroneously in the West Indies, but in fact is more than 1,000 miles to the north of the Caribbean” (Caribbean Publishing Company: 51). -

The Sound of William Barnes's Dialect Poems

Welcome to the electronic edition of The Sound of William Barnes’s Dialect Poems: 3. Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect, third collection (1862). The book opens with the bookmark panel and you will see the contents page. Click on this anytime to return to the contents. You can also add your own bookmarks. Each chapter heading in the contents table is clickable and will take you direct to the chapter. Return using the contents link in the bookmarks. The whole document is fully searchable. Enjoy. The Sound of William Barnes’s Dialect Poems 3. Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect, third collection About this volume This is the third volume in a series that sets out to provide a phonemic transcript and an audio recording of each individual poem in Barnes’s three collections of Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect. Its 96 poems include some of those most loved and admired: poems of heart-wrenching grief at the untimely deaths of Barnes’s wife, Julia (“Woak Hill”), and their young son, Julius “The turnstile”); celebrations of love anticipated (“In the spring”) and love fulfilled (“Don’t ceäre”); protests against injustice and snobbery (“The love child”); struggles to accept God’s will (“Grammer a-crippled”); comic poems (“John Bloom in Lon’on”, “A lot o’ maïdens a-runnèn the vields”); and poems on numerous other subjects, with an emotional range stretching from the deepest of grief to the highest of joy. The metrical forms show astonishing versatility, from straightforward octosyllabic couplets to challenging rhyme-schemes and innovative stanzaic patterns, widely varied line-lengths, and skilful adaptations of rhetorical devices from other languages. -

The Perception and Production of Stress and Intonation by Children with Cochlear Implants

THE PERCEPTION AND PRODUCTION OF STRESS AND INTONATION BY CHILDREN WITH COCHLEAR IMPLANTS ROSEMARY O’HALPIN University College London Department of Phonetics & Linguistics A dissertation submitted to the University of London for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2010 ii ABSTRACT Users of current cochlear implants have limited access to pitch information and hence to intonation in speech. This seems likely to have an important impact on prosodic perception. This thesis examines the perception and production of the prosody of stress in children with cochlear implants. The interdependence of perceptual cues to stress (pitch, timing and loudness) in English is well documented and each of these is considered in analyses of both perception and production. The subject group comprised 17 implanted (CI) children aged 5;7 to 16;11 and using ACE or SPEAK processing strategies. The aims are to establish (i) the extent to which stress and intonation are conveyed to CI children in synthesised bisyllables (BAba vs. baBA) involving controlled changes in F 0, duration and amplitude (Experiment I), and in natural speech involving compound vs. phrase stress and focus (Experiment II). (ii) when pitch cues are missing or are inaudible to the listeners, do other cues such as loudness or timing contribute to the perception of stress and intonation? (iii) whether CI subjects make appropriate use of F 0, duration and amplitude to convey linguistic focus in speech production (Experiment III). Results of Experiment I showed that seven of the subjects were unable to reliably hear pitch differences of 0.84 octaves. Most of the remaining subjects required a large (approx 0.5 octave) difference to reliably hear a pitch change. -

The Interface Between English and the Celtic Languages

Universität Potsdam Hildegard L. C. Tristram (ed.) The Celtic Englishes IV The Interface between English and the Celtic Languages Potsdam University Press In memoriam Alan R. Thomas Contents Hildegard L.C. Tristram Inroduction .................................................................................................... 1 Alan M. Kent “Bringin’ the Dunkey Down from the Carn:” Cornu-English in Context 1549-2005 – A Provisional Analysis.................. 6 Gary German Anthroponyms as Markers of Celticity in Brittany, Cornwall and Wales................................................................. 34 Liam Mac Mathúna What’s in an Irish Name? A Study of the Personal Naming Systems of Irish and Irish English ......... 64 John M. Kirk and Jeffrey L. Kallen Irish Standard English: How Celticised? How Standardised?.................... 88 Séamus Mac Mathúna Remarks on Standardisation in Irish English, Irish and Welsh ................ 114 Kevin McCafferty Be after V-ing on the Past Grammaticalisation Path: How Far Is It after Coming? ..................................................................... 130 Ailbhe Ó Corráin On the ‘After Perfect’ in Irish and Hiberno-English................................. 152 II Contents Elvira Veselinovi How to put up with cur suas le rud and the Bidirectionality of Contact .................................................................. 173 Erich Poppe Celtic Influence on English Relative Clauses? ......................................... 191 Malcolm Williams Response to Erich Poppe’s Contribution