Independent Review of Kalamazoo Department of Public Safety in Two

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treading the Thin Blue Line: Military Special-Operations Trained Police SWAT Teams and the Constitution

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 9 (2000-2001) Issue 3 Article 7 April 2001 Treading the Thin Blue Line: Military Special-Operations Trained Police SWAT Teams and the Constitution Karan R. Singh Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons Repository Citation Karan R. Singh, Treading the Thin Blue Line: Military Special-Operations Trained Police SWAT Teams and the Constitution, 9 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 673 (2001), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol9/iss3/7 Copyright c 2001 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj TREADING THE THIN BLUE LINE: MILITARY SPECIAL-OPERATIONS TRAINED POLICE SWAT TEAMS AND THE CONSTITUTION The increasing use of SWAT teams and paramilitaryforce by local law enforcement has been thefocus of a growingconcern regardingthe heavy-handed exercise of police power. Critics question the constitutionality ofjoint-training between the military and civilian police, as well as the Fourth Amendment considerationsraised by SWAT tactics. This Note examines the history, mission, and continuing needfor police SWAT teams, addressingthe constitutionalissues raisedconcerning training and tactics. It explains how SWATjoint-training with the military is authorized by federal law and concludes that SWAT tactics are constitutionallyacceptable in a majority of situations. Though these tactics are legal andconstitutionally authorized, this Note acknowledges the validfearscritics have regarding the abuse of such police authority, and the limitations of constitutionaltort jurisprudence in adequately redressingresulting injuries. INTRODUCTION Americans awoke on the morning of April 23,2000 to news images seemingly taken from popular counterterrorist adventure movies. -

Blue Lives Matter

COP FRAGILITY AND BLUE LIVES MATTER Frank Rudy Cooper* There is a new police criticism. Numerous high-profile police killings of unarmed blacks between 2012–2016 sparked the movements that came to be known as Black Lives Matter, #SayHerName, and so on. That criticism merges race-based activism with intersectional concerns about violence against women, including trans women. There is also a new police resistance to criticism. It fits within the tradition of the “Blue Wall of Silence,” but also includes a new pro-police movement known as Blue Lives Matter. The Blue Lives Matter movement makes the dubious claim that there is a war on police and counter attacks by calling for making assaults on police hate crimes akin to those address- ing attacks on historically oppressed groups. Legal scholarship has not comprehensively considered the impact of the new police criticism on the police. It is especially remiss in attending to the implications of Blue Lives Matter as police resistance to criticism. This Article is the first to do so. This Article illuminates a heretofore unrecognized source of police resistance to criticism by utilizing diversity trainer and New York Times best-selling author Robin DiAngelo’s recent theory of white fragility. “White fragility” captures many whites’ reluctance to discuss ongoing rac- ism, or even that whiteness creates a distinct set of experiences and per- spectives. White fragility is based on two myths: the ideas that one could be an unraced and purely neutral individual—false objectivity—and that only evil people perpetuate racial subordination—bad intent theory. Cop fragility is an analogous oversensitivity to criticism that blocks necessary conversations about race and policing. -

William H. Parker and the Thin Blue Line: Politics, Public

WILLIAM H. PARKER AND THE THIN BLUE LINE: POLITICS, PUBLIC RELATIONS AND POLICING IN POSTWAR LOS ANGELES By Alisa Sarah Kramer Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History Chair: Michael Kazin, Kimberly Sims1 Dean o f the College of Arts and Sciences 3 ^ Date 2007 American University Washington, D.C. 20016 AMERICAN UNIVERSITY UBRARY Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3286654 Copyright 2007 by Kramer, Alisa Sarah All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 3286654 Copyright 2008 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. © COPYRIGHT by Alisa Sarah Kramer 2007 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. I dedicate this dissertation in memory of my sister Debby. -

'Blue Line,' Or Crossing a Line?

Bill Lynch: Tear down this wall School bell blues UGB isn’t what we thought. A6 ■ Groggy students just got a reprieve Sports: Scheduling conflict from the Governor, who signed a bill Power outage cancels games. A8 mandating later school start times. SEE A3 Schools: Homecoming week Siss-boom-bah, Sonoma-style. A9 Tuesday, October 15, 2019 Our 138th Year Serving Sonoma Valley Sonoma Valley, California ■ SonomaNews.com An edition of The Press Democrat Blackout fallout: Shutdown was ‘economic disaster’ 95 percent of businesses closed, estimates Chamber CEO By ANNE WARD ERNST economy. the community’s basic needs and INDEX-TRIBUNE STAFF WRITER “Obviously, this was an eco- minimize the impact.” The PG&E-imposed blackout nomic disaster for our location,” Jack Burkam, general manager last week affected businesses said Mark Bodenhamer, CEO of the Best Western Inn, said there throughout Sonoma Valley, press- of Sonoma Valley Chamber of hasn’t been a noticeable injurious ing managers and business owners Commerce. “Ninety-five percent fallout from the power outage in into creative-thinking mode – and of our businesses were shut down the short-term. ROBBI PENGELLY/INDEX-TRIBUNE left some wondering what the and those businesses that were Joe Hencmann gave away free ice cream during the outage. long-term effects will be on the open made a valiant effort to serve See Blackout, A5 ■■ CONTROVERSY ■ SDC plant closure puts ‘Blue line,’ or crossing a line? water officials on edge One-day water supply in an emergency, warns VOMWD manager By CHRISTIAN KALLEN INDEX-TRIBUNE STAFF WRITER First the electrical grid, now the water supply is being identi- fied as one of the necessities of modern life that may be at risk in case of disaster. -

Police Discipline: a Case for Change

New Perspectives in Policing J U N E 2 0 1 1 National Institute of Justice Police Discipline: A Case for Change Darrel W. Stephens Introduction Executive Session on Policing and Police disciplinary procedures have long been a Public Safety source of frustration for nearly everyone involved This is one in a series of papers that will be pub in the process and those interested in the out lished as a result of the Executive Session on Policing and Public Safety. comes. Police executives are commonly upset by the months — and sometimes years — it takes Harvard’s Executive Sessions are a convening from an allegation of misconduct through the of individuals of independent standing who take joint responsibility for rethinking and improving investigation and resolution. Their frustration is society’s responses to an issue. Members are even greater with the frequency with which their selected based on their experiences, their repu decisions are reversed or modified by arbitrators, tation for thoughtfulness and their potential for helping to disseminate the work of the Session. civil service boards and grievance panels. Police officers and their unions generally feel discipline In the early 1980s, an Executive Session on Policing is arbitrary and fails to meet the fundamental helped resolve many law enforcement issues of the day. It produced a number of papers and requirements of consistency and fairness. Unless concepts that revolutionized policing. Thirty years it is a high-profile case or one is directly involved, later, law enforcement has changed and NIJ and few in the community are interested in the police Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government are again collaborating to help resolve law enforce disciplinary process. -

Neighborhoods and Police: the Maintenance of Civil Authority I by Georgel

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs National*I~~tituteof Justice May 1989 No. 10 A publication of the National Institute of Justice, U.S. Department of Justice, and the Program in Criminal Justice Policy and Management, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University 1, II 1 Neighborhoods and Police: The Maintenance of Civil Authority I By George L. -

Police and Communities: the Quiet Revolution

U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice ': June 1988 No. 1 A publication of the National Institute of Justice, U.S. Department of Justice, and the Program in Criminal Justice Policy and Management, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University Police and Communities: 9y r L the Quiet Revolution - + By George L. Kelling a tT+Aw*y Introduction This is one in a series of reports originally developed with A quiet revolution is reshaping American policing. some of the leading figures in American policing during their periodic meetings at Harvard University's John F. Police in dozens of communities are returning to foot Kennedy School of Government. The reports are published patrol. In many communities, police are surveying citi- so that Americans interested in the improvement and the zens to learn what they believe to be their most serious future of policing can share in the information and perspec- neighborhood problems. Many police departments are tives that were part of extensive debates at the School's finding alternatives to rapidly responding to the majority Executive Session on Policing. of calls for service. Many departments are targeting re- The police chiefs, mayors, scholars, and others invited to sources on citizen fear of crime by concentrating on dis- the meetings have focused on the use and promise of such order. organizing citizens' groups has become a priority strategies as community-based and problem-oriented polic- in many departments. Increasingly, police departments ing. The testing and adoption of these strategies by some are looking for means to evaluate themselves on their police agencies signal important changes in the way Amer- contribution to the quality of neighborhood life, notjust ican policing now does business. -

Full Report (PDF)

STRESS ON THE STREETS (SOS): RACE, POLICING, HEALTH, AND INCREASING TRUST NOT TRAUMA FULL PROJECT REPORT www.trustnottrauma.org #trustnottrauma December 2015 By Human Impact Partners With the partnership of: Ohio Justice & Policy Center Ohio Organizing Collaborative For more information about Human Impact Partners, please see www.humanimpact.org. 1 AUTHORED BY: Sara Satinsky Kim Gilhuly Afomeia Tesfai Jonathan Heller Selam Misgano SUGGESTED CITATION: Human Impact Partners. December 2015. Stress on the Streets (SOS): Race, Policing, Health, and Increasing Trust not Trauma. Oakland, CA. FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT: Sara Satinsky Human Impact Partners [email protected] www.humanimpact.org 510-452-9442, ext. 104 Human Impact Partners is a national nonprofit working to transform the policies and places people need to live healthy lives by increasing the consideration of health and equity in decision making. 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For their valuable guidance, feedback on process and materials, and support we extend deep thanks to the report Advisory Committee. For sharing experiences and time, our sincere thanks to focus group participants, survey participants, and key informant interviews. Our gratitude goes to the Cincinnati Police Department for sharing data. We thank the staff at various agencies and organizations for providing and interpreting health data: Jennifer Chubinski at Interact for Health; Chip Allen, Jillian Garratt, Holly Sobotka, and Brandi Robinson at Ohio Department of Health; Camille Jones and Noble Maseru at Cincinnati Health Department; Monique Harris at Summit County Public Health. Thanks also to the following for providing neighborhood-level information: Mike Meyer at the Akron Department of Planning and Urban Development, and Rekha Kumar in Cincinnati Department of City Planning. -

Police Use of Social Media As Bureaucratic Propaganda: Comments on State Violence and Law Enforcement Use of Social Media in 2020

VOLUME 22, ISSUE 2, PAGES 25 – 32 (2021) Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society E-ISSN 2332-886X Available online at https://scholasticahq.com/criminology-criminal-justice-law-society/ Police Use of Social Media as Bureaucratic Propaganda: Comments on State Violence and Law Enforcement Use of Social Media in 2020 Christopher J. Schneider Brandon University A B S T R A C T A N D A R T I C L E I N F O R M A T I O N Police are recognized as primary producers of social order, and social media factor into the process of gaining the co- operation of citizens in ways that serve the interests of police. In this short commentary piece, I provide an overview of police use of social media and highlight some recent thematic examples from 2020 to illustrate how police use of social media is consistent with Altheide and Johnson’s (1980) concept of “bureaucratic propaganda,” the aim of which is to sustain the appearance of institutional legitimacy in the form of official information. Article History: Keywords: Received April 9th, 2021 police, social media, propaganda, bureaucratic propaganda, social control Received in revised form June 12th, 2021 th Accepted July 9 , 2021 © 2021 Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society and The Western Society of Criminology Hosting by Scholastica. All rights reserved. Corresponding author: Christopher J. Schneider, PhD, Brandon University 270 18th Street, Brandon, Manitoba, R7A 6A9, Canada Email: [email protected] 2 SCHNEIDER The year 2020 has been called the year of logic of social media is very much the opposite - non- protests. -

The Blurred Blue Line: Reform in an Era of Public & Private Policing

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Law School Spring 2017 The Blurred Blue Line: Reform in an Era of Public & Private Policing Seth W. Stoughton Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/law_facpub Part of the Law Commons Article THE BLURRED BLUE LINE: REFORM IN AN ERA OF PUBLIC & PRIVATE POLICING Seth W. Stoughton* I. Introduction ........................................................................................ 117 II. The Evolution of Public and Private Policing .................................... 119 III. The Blurring of the Blue Line ............................................................ 127 IV. Police Reform & the Blurred Blue Line ............................................. 146 V. Conclusion .......................................................................................... 154 I. INTRODUCTION In April 2017, the Alabama Senate voted to authorize the formation of a new police department. Like other officers in the state, officers at the new agency would have to be certified by the Alabama Peace Officers Standards and Training Commission. These new officers would be “charged with all of the duties and invested with all of the powers of law enforcement officers.”1 Unlike most officers in Alabama, though, the officers at the new agency would not be city, county, or state employees. Instead, they would be working for the Briarwood Presbyterian Church, which would be authorized under * Assistant Professor of Law, University of South Carolina School of Law. I am grateful to Geoff Alpert, Colin Miller, and Nick Selby for their helpful comments and suggestions. I am thankful for the research assistance of Emily Bogart, Ashlea Carver, Courtney Huether, and Colton Driver, and for the editorial assistance provided by the American Journal of Criminal Law. As always, I am deeply grateful for the support of Alisa Stoughton. -

Crossing the Thin Blue Line: Protecting Law Enforcement Officers Who Blow the Whistle, 52 U

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2018 Crossing the Thin lueB Line: Protecting Law Enforcement Officers Who Blow the Whistle Ann C. Hodges University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/law-faculty-publications Part of the Labor and Employment Law Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons Recommended Citation Ann C. Hodges & Justin Pugh, Crossing the Thin Blue Line: Protecting Law Enforcement Officers Who Blow the Whistle, 52 U. C. Davis L. Rev. Online, June 2018. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Crossing the Thin Blue Line: Protecting Law Enforcement Officers Who Blow the Whistle Ann C. Hodges and Justin Pugh* Law enforcement makes headline news for shootings of unarmed civilians, departmental corruption, and abuse of suspects and witnesses. Also well-documented is the code of silence, the thin blue line, which discourages officers from reporting improper and unlawful conduct by fellow officers. Accordingly, accountability is challenging and mistrust of law enforcement abounds. There is much work to be done in changing the culture of police departments and many recommendations for change. One barrier to transparency that has been largely ignored could be eliminated by reversal of the Supreme Court’s 2006 decision in Garcetti v. Ceballos. Criticism of the decision has been widespread, but its specific consequences for law enforcement officers who cross the thin blue line remain little examined in the legal literature. -

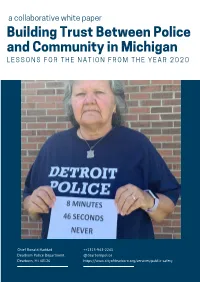

Building Trust Between Police and Community in Michigan, Lessons

a collaborative white paper Building Trust Between Police and Community in Michigan L E S S O N S F O R T H E N A T I O N F R O M T H E Y E A R 2 0 2 0 Chief Ronald Haddad ++1313-943-2241 Dearborn Police Department @dearbornpolice Dearborn, MI 48126 https://www.cityofdearborn.org/services/public-safety EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Crossing the Thin Blue Line This white paper is intended partly as a wake-up call, partly as a review of promising practices and partly as a message of hope. The authors include police chiefs, prosecutors, public health experts, professors, civil rights advocates and others. Our intended audience consists of policymakers, professionals and members of the public who are looking for meaningful responses to the complex challenges that we face, not just in revolutionary slogans or knee-jerk defenses of an unsustainable status quo. Policing is indeed plagued with problems, but most American communities still value their police, especially when they are properly doing their jobs, truly protecting all the people that they serve. American attitudes towards police are complex. Recent polling conducted in Minneapolis, where the “Defund the Police” movement gained momentum in the wake of George Floyd’s murder by police, suggest that the majority of residents oppose out-and-out defunding of police, and that these majorities are actually higher among Black residents.[1] On the other hand, residents across the board are overwhelmingly in favor of shifting public funding away from arming police and towards more social services.