William H. Parker and the Thin Blue Line: Politics, Public

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Board Meeting Packet

Board of Directors Board Meeting Packet October 6, 2020 SPECIAL NOTICE REGARDING PUBLIC PARTICIPATION AT THE EAST BAY REGIONAL PARK DISTRICT BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING SCHEDULED FOR TUESDAY, October 6, 2020 at 1:00 PM Pursuant to Governor Newsom’s Executive Order No. N-29-20 and the Alameda County Health Officer’s Shelter in Place Orders, the East Bay Regional Park District Headquarters will not be open to the public and the Board of Directors and staff will be participating in the Board meetings via phone/video conferencing. Members of the public can listen and view the meeting in the following way: Via the Park District’s live video stream which can be found at: https://youtu.be/kJbeyUhx9I8 Public comments may be submitted one of three ways: 1. Via email to Yolande Barial Knight, Clerk of the Board, at [email protected]. Email must contain in the subject line public comments – not on the agenda or public comments – agenda item #. It is preferred that these written comments be submitted by Monday, October 5, 2020 at 3:00pm. 2. Via voicemail at (510) 544-2016. The caller must start the message by stating public comments – not on the agenda or public comments – agenda item # followed by their name and place of residence, followed by their comments. It is preferred that these voicemail comments be submitted by Monday, October 5, 2020 at 3:00 pm. 3. Live via zoom. If you would like to make a live public comment during the meeting this option is available through the virtual meeting platform: https://zoom.us/j/92631111514 * Note that this virtual meeting platform link will let you into the virtual meeting for the purpose of providing a public comment. -

The Importance of Training and Education in the Professionalization of Law Enforcement*

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 52 Article 11 Issue 1 May-June Summer 1961 The mpI ortance of Training and Education in the Professionalization of Law Enforcement George H. Brereton Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation George H. Brereton, The mporI tance of Training and Education in the Professionalization of Law Enforcement, 52 J. Crim. L. Criminology & Police Sci. 111 (1961) This Criminology is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. POLICE SCIENCE THE IMPORTANCE OF TRAINING AND EDUCATION IN THE PROFESSIONALIZATION OF LAW ENFORCEMENT* GEORGE H. BRERETON George H. Brereton is Deputy Director, Department of Justice, for the State of California. Mr. Brereton has had wide experience in the law enforcement field, serving at one time with the Berkeley Police Department, subsequently as Director of the Police Training School, San Jose (California) State College, and with the California State Department of Education ap First State Supervisor of Peace Officers' Training. Mr. Brereton has also served as Chief of the Bureau of Criminal Identifica- tion and Investigation and as Assistant Director, Division of Criminal Law and Enforcement, Department -

1996 Annual Report

Los Angeles Police Department Annual Report 1996 Mission Statement 1996 Mission Statement of the Los Angeles Police Department Our mission is to work in partnership with all of the diverse residential and business communities of the City, wherever people live, work, or visit, to enhance public safety and to reduce the fear and incidence of crime. By working jointly with the people of Los Angeles, the members of the Los Angeles Police Department and other public agencies, we act as leaders to protect and serve our community. To accomplish these goals our commitment is to serve everyone in Los Angeles with respect and dignity. Our mandate is to do so with honor and integrity. Los Angeles Mayor and City Council 1996 Richard J. Riordan, Mayor Los Angeles City Council Back Row (left to right): Nate Holden, 10th District; Rudy Svorinich, 15th District; Rita Walters, 9th District; Richard Alarcón, 7th District; Laura Chick, 3rd District; Hal Bernson, 12th District; Michael Feuer, 5th District; Mark Ridley-Thomas, 8th District; Jackie Goldberg, 13th District; Richard Alatorre, 14th District Front Row (left to right): Ruth Galanter, 6th District; Joel Wachs, 2nd District; John Ferraro, President, 4th District; Mike Hernandez, 1st District; Marvin Braude, President Pro-Tempore, 11th District Board of Police Commissioners 1996 Raymond C. Fisher, President Art Mattox, Vice-President Herbert F. Boeckmann II, Commissioner T. Warren Jackson, Commissioner Edith R. Perez, Commissioner Chief's Message 1996 As I review the past year, the most significant finding is that for the fourth straight year crime in the City of Los Angeles is down. -

Attachment 1

ATTACHMENT 1 SELECTED INDEPENDENT AND COMMISSIONED REPORTS AND COURT DECISIONS • The President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing and Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (Washington, D.C.: Office for Community Oriented Policing Services, 2015). Synopsis and link to reports: • Widely viewed as a very significant document for law enforcement in recent years. President Obama’s charge in 2014: “examine ways of fostering strong, collaborative relationships between local law enforcement and the communities they protect and to make recommendations to the President on the ways policing practices can promote effective crime reduction while building public trust.” Report presented 156 recommendations across 6 key areas: 1) building trust and legitimacy, 2) policy and oversight, 3) technology and social media, 4) community policing and crime reduction, 5) training and education, and 6) officer wellness and safety. • http://www.cops.usdoj.gov/pdf/taskforce/TaskForce_FinalReport.pdf. • Related report: An Evidence-Assessment of the Recommendations of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing — Implementation and Research Priorities. Lum, C., Koper, C.S., Gill, C., Hibdon, J., Telep, C. & Robinson, L. (2016) Fairfax, VA: Center for Evidence- Based Crime Policy, George Mason University. Alexandria, VA: International Association of Chiefs of Police. Synopsis and link to report: • Created as a research reference for agencies seeking guidance on implementation of the recommendations of the Task Force. • https://www.theiacp.org/sites/default/files/all/i- j/IACP%20GMU%20Evidence%20Assessment%20Report%20FINAL.pdf • See also the IACP’s Blueprint for 21st Century Policing: www.theiacp.org/icpr • Supreme Court of California “The Regents of the University of California v. -

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

The History of Policing 97

THE HISTORY 4 OF POLICING distribute or post, copy, not Do Copyright ©2015 by SAGE Publications, Inc. This work may not be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without express written permission of the publisher. “The myth of the unchanging police “You never can tell what a man is able dominates much of our thinking about to do, but even though I recommend the American police. In both popular ten, and nine of them may disappoint discourse and academic scholarship one me and fail, the tenth one may surprise continually encounters references to the me. That percentage is good enough for ‘tradition-bound’ police who are resistant me, because it is in developing people to change. Nothing could be further from that we make real progress in our own the truth. The history of the American society.” police over the past one hundred years is —August Vollmer (n.d.) a story of drastic, if not radical change.” —Samuel Walker (1977) distribute INTRODUCTION: POLICING LEARNING OBJECTIVES or After finishing this chapter, you should be able to: AS A DYNAMIC ENTITY Policing as we know it today is relatively new. 4.1 Summarize the influence of early The notion of a professional uniformed police officer English policing on policing and the receiving specialized training on the law, weapon use, increasing professionalization of policing and self-defense is taken for granted. In fact, polic- in the United States over time. post,ing has evolved from a system in which officers ini- tially were appointed by friends, given no training, 4.2 Identify how the nature of policing in the provided power to arrest without warrants, engaged United States has changed over time. -

Bugsy Siegel Part 30 of 32

FEDERAL OF STiGA'iION BQQQK 5'/£6EL PART #i%// W0/C // 7 PAGES AVAILABLETHIS PART???lg 17/ _ FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION FILES CONTAINED IN THIS PART A FILE # /0 -0 .-. 92 _ b_§"_.Q L,_.' '/.J ég: 3/$/3 ..§§*c 4}-Z_§/Z_L92fo_/./_2___PAGES AVAILABLE I & .. A 2 LL __-ll,1_,92!Z vo/.1! T ief _. 7 ya _ _ .. éz-1*'1._!..2....__.__._ v@/-2! ¢z-as/2 v<>/.~/!35 _-.""'.....-2;.-::.'.: :.=- .-"'='-"-s -*=.=-*=i~>*'*'"@~'.'------~.--*--~*-'- -- -* .1. ' w- 0 _ - __ . I; 1 ._ 0 _ A_ A-~-{in . V _ VP 3 0 ' . 0- . .;§ - -~ £11.: osscnwon . »i-_: I? Q . .- D . ;;;.~ ¢-§- . aumzau me % -'-- £ ' --. ._.4 _ I-r-"P - -. I Q -1» Q jO &$.U_BJECT /6?/és?i§§¢'@¢=4 Y .0 FILE N0.__; /~'>-*/$>.%__... ' /7 L sscfnowmo. 92--.5 _ . I 1- . -. O 0 _ . ' _ ;'1 _ . 8 ; SE'RlALS.____.i_________..% ' '9 /u - '4 --iv-< 1I - "E I -0 . - 1°} Y __- -bi.-¥ . -i "." _ " " '-:_'u--4 = Q 1 ll 1-._ ..-_- .. - .- I '5 _ _ - ' - r0 - -- 3 ___ _ . ' . ...-. .-. ' ; -_.~.., -. _ ... ,...- ...,_~.. ., .-4._,, .,..._,.¢a-__.. ... _-.-...-¢....._,_.....u._-.....@ _ ..v__ ... V_.m. 92 ..._..... mg; >?i492llAlIl*y-Q9292 .... ..= .... , 4. ,.,, , in hon ttoaglt gag .<. in Into 6 Int, j 811109 ' cuc M00010 £3101-00904 la an D 1 IO_I"II0L'.~_'-,0 0 QM liliiiiingj gs-_' IPPMI if III Icfhr 5,-_ QCPIII flat III 9* - should In I11"! ' |-- .[-,,¢ V. -

![Algapo]Ie Mavie](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0525/algapo-ie-mavie-410525.webp)

Algapo]Ie Mavie

ALGAPO]IE MAVIE I l,l lmdl ,do*o6oo, El Dapel de la Coca www.matUacoca.org PREFACE AL CAPONE, SA VIE... On peut obtenir beaucoup plus,avec un mot gentil et un revolver, qu'avec un mot gentil tout seul (Attribu6 I Al Capone) Al Capone est sans doute avec Pablo Escobar, le criminel le plus cilEbre du monde. Et les deux hommes partagent nombre de points communs: une origine modeste, mais pas pauvre, une envie de s'impliquer dans la politique et rsBN 978-2-35887 -L26-6 une mddiatisation I outrance qui a particip6 i leur chute. (tssN 978-2-35 887 -097 -9, 1'" publication) Cette mddiatisation leur a attir6 non seulement la coldre des autoritds, qui ont mis tout en euvre pour les faire tomber, Si vous souhaitez recevoir notre catalogue mais 6galement de leurs associds, m6contents d'attirer sur et 6tre tenu au courant de nos publications, eirx les lumidres des m6dias. envoyez vos nom et adresse, en citant ce livre I: Dans les ann6es trente, Al Capone a 6t6 le symbole du crime en Amdrique, son nom 6tant attachd I jamais i la La Manufacture de livres, 101 rue de Sdvres, 75006 Paris ou folle pCriode de la prohibition. Le < boss > de Chicago est [email protected] devenu cdldbre par ses interviews i la presse, reprises par les journaux europdens. Sa c6l6britd est telle qu'un te code de la propridtd intellduelle interdit les copies ou reproductions destin6es e une utilisation colledive. Toule repr6sentation ou reproduciion int6grale ou panielle faite par quelques proc6d6s journaliste ddtective va se mettre au travers de sa route. -

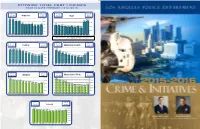

Crimes and Initiatives 2015

‘15 vs ‘05 Total Part I Crime ‘15 vs ‘14 ‘15 vs ‘05 Rape ‘15 vs ‘14 Homicide 120,000 Rape 116,532 1,800 103,492 1,649 489 480 100,000 1,600 500 2000 1,512 1,400 395 80,000 384 1649 1,200 1,105 400 1512 1,059 60,000 1,004 1,000 312 1500 949 293 297 299 903 923 936 828 283 40,000 260 764 800 251 300 11051059 1004 600 949 903 923 936 20,000 1000 828 764 400 200 - 200 - 100 500 2014 2015 92,096 92,096 0 0 2005 2006 2007 2008CITYWIDE2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 TOTAL2015 PART2005 2006 2007 2008 I2009 CRIMES2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 *Rape Stats prior to 2014 were updated to include additional Crime Class Codes YEAR to DATE THROUGH 12/31/2015 that have been added to the UCR Guidelines for the crime of Rape. ‘15 vs ‘05 ‘15 vs ‘14 ‘15 vs ‘05 ‘15 vs ‘14 Homicide Robbery ‘15 vs ‘05AggravatedRape AssaultsRobbery ‘15 vs ‘14 Homicide ‘15 vs ‘05 ‘15 vs ‘14 489 16,000 Rape 489 480 500 480 2000 500 Aggravated Assaults 2000 14,353 14,353 15000 13,797 20000 18,000 13,797 1649 14,000 13,481395 13,422 13,481 13,422 384 395 1512 16,376 1649 384 12,217 16,000 12,217 16,376 12,000 400 400 14,634 1512 10,924 12000 14,634 14,000 312 10,924 10,077 1500 13,569 1500 293 297 299 312 13,569 10,000 15000 12,926 10,077 8,983 8,935 11,798 283 1105 12,926 293 297 299 12,000 260 1059 7,885 7,940 283 11,798 8,000 1105 10,638 89,83 251 8,935 300 1004 949 260 300 1059 10,615 903 923 936 251 1004 10,000 7,885 7,940 9000 10,638 828 10,615 949 9,344 903 8,843 923 936 764 6,000 1000 8,329 1000 9,344 8,843 10000 828 8,000 8,329 7,624 764 200 7,624 4,000 200 6000 6,000 2,000 500 4,000 500 100 5000 100 3000 - 2,000 - 0 0 0 0 92,096 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 201392,0962014 2015 0 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 20140 2015 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2005200520062006200720072008200820092009201020102011201120122012201320132014201420152015 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 *Rape Stats prior to 2014 were updated to include additional Crime Class Codes that have been added to the UCR Guidelines for the crime of Rape. -

Nebraska's Unique Contribution to the Entertainment World

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Nebraska’s Unique Contribution to the Entertainment World Full Citation: William E Deahl Jr, “Nebraska’s Unique Contribution to the Entertainment World,” Nebraska History 49 (1968): 282-297 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1968Entertainment.pdf Date: 11/23/2015 Article Summary: Buffalo Bill Cody and Dr. W F Carver were not the first to mount a Wild West show, but their opening performances in 1883 were the first truly successful entertainments of that type. Their varied acts attracted audiences familiar with Cody and his adventures. Cataloging Information: Names: William F Cody, W F Carver, James Butler Hickok, P T Barnum, Sidney Barnett, Ned Buntline (Edward Zane Carroll Judson), Joseph G McCoy, Nate Salsbury, Frank North, A H Bogardus Nebraska Place Names: Omaha Wild West Shows: Wild West, Rocky Mountain and Prairie Exhibition -

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Police Brutality And

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Police Brutality and Communities of Color A graduate project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Public Administration in Public Sector Management and Leadership By Edith Jacqueline Gonzalez August 2019 i The thesis of Edith Jacqueline Gonzalez is approved: _________________________________________ ______________ Dr. Sarmistha Majumdar Date _________________________________________ ______________ Dr. Boris Ricks Date _________________________________________ ______________ Dr. Henrik Minassians, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Dedication Above all I would like to thank God almighty for giving me the strength and determination to complete this Master’s program. I am grateful to everyone who believed in me and encouraged my journey to higher education. I would like to dedicate this research project to my mother, who crossed borders so that that I could be here. Mom, thank you for making the biggest sacrifice—leaving your family, leaving your country, leaving everything you knew to provide me with the opportunities you never had. I am the product of your sacrifices, hard work, and love. Thank you for being the shining example of what I wanted to be, for every hug, every prayer, word of encouragement, and act of love. All that I am or hope to be, I owe to you. To my younger siblings, Stephanie and Genesis, whom without knowing it inspired me to pursue higher education. If I can do it, you can do it too. For every first generation student -

Courier Gazette : October 19, 1939

IsS8UED J g ESDAY ItoURSDffiT Saturday he ourier azette T Entered is Second ClassC Mail Matter -G Established January, 1846 By The Courier-Gazette, 465 Main St. Rockland, Maine, Thursday, October 19, 1939 TWELVE PAGES V o lu m e 9 4 ....................Number 125. The Courier-Gazette [EDITORIAL] THREE-TIMES * WEEK HELLO DAD,” SAID HELVI HELD UP FEYLER’SLOBSTERS AIR AGAINST SEA Editor “The Black Cat” WM O FULLER Apropos of an editorial which appeared in this column Associate Editor At the Bell telephone exhibit at This Is going to be good, thought Tuesday is the rapidly dawning belief that the skies hold the FRANK A, WINSLOW the World's Fair 150 persons daily the other listeners, and they gave Union Trucks Place Ban On Rockland Concern, destinies of battles which will be fought in the future. Under arc permitted to talk free to any careful attention. Subscription* 43 00 per year payable the caption "Air Against Sea." the Press Herald yesterday said: In advance: single copies three cents. point In the United States, the And then, with gatling rapidity For Reason Unknown To It Advertising rate* baaed upon circula Defense is easier than offense, sav military tacticians, tion and very reasonable privilege determined by the draw Helvi began to talk to "dad" in writing of land operations. But what of the air? Here small NEWSPAPER HISTORY ing of lucky numbers. Finnish. handfuls of German planes have succeeded in doing consider (Press Herald) The Rockland Gazette was estab In attendance one night recently The 300 listeners put down their Commissioner of Sea and Shore able damage and ln causing a great deal of consternation lished In 1846.