1 Spawning of Black Grouper (Mycteroperca Bonaci

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modeling Gag Grouper (Mycteroperca Microlepis

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2009 Modeling gag grouper (Mycteroperca microlepis) in the Gulf of Mexico: exploring the impact of marine reserves on the population dynamics of a protogynous grouper Robert D. Ellis Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons Recommended Citation Ellis, Robert D., "Modeling gag grouper (Mycteroperca microlepis) in the Gulf of Mexico: exploring the impact of marine reserves on the population dynamics of a protogynous grouper" (2009). LSU Master's Theses. 4146. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4146 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MODELING GAG GROUPER (MYCTEROPERCA MICROLEPIS) IN THE GULF OF MEXICO: EXPLORING THE IMPACT OF MARINE RESERVES ON THE POPULATION DYNAMICS OF A PROTOGYNOUS GROUPER A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in The Department of Oceanography and Coastal Sciences by Robert D. Ellis B.S., University of California Santa Barbara, 2004 August 2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the State of Louisiana Board of Regents for funding this research with an 8G Fellowship. My research and thesis were greatly improved by the comments and assistance of many people, first among them my advisor Dr. -

Age Estimates of Two Large Misty Grouper, Epinephelus Mystacinus

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Aquila Digital Community Gulf and Caribbean Research Volume 21 | Issue 1 2009 Age Estimates of Two Large Misty Grouper, Epinephelus mystacinus (Serranidae) from Bermuda with a Comparison of the Age of Tropical Groupers in the Western Atlantic Brian E. Luckhurst Marine Resources Division, Bermuda John M. Dean University of South Carolina DOI: 10.18785/gcr.2101.09 Follow this and additional works at: http://aquila.usm.edu/gcr Part of the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Luckhurst, B. E. and J. M. Dean. 2009. Age Estimates of Two Large Misty Grouper, Epinephelus mystacinus (Serranidae) from Bermuda with a Comparison of the Age of Tropical Groupers in the Western Atlantic. Gulf and Caribbean Research 21 (1): 73-77. Retrieved from http://aquila.usm.edu/gcr/vol21/iss1/9 This Short Communication is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gulf and Caribbean Research by an authorized editor of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gulf and CaribbeanGulf Research and Caribbean Vol 21, 73-77,Research 2009 Vol 21, 73-77, 2009 Manuscript receivedManuscript January 7,received 2009; Januaryaccepted 7, February 2009; accepted 6, 2009 February 6, 2009 Gulf and Caribbean Research Vol 21, 73-77, 2009 Manuscript received January 7, 2009; accepted February 6, 2009 SHORT COMMUNICATIONSHORT COMMUNICATION SHORT COMMUNICATION AGE ESTIMATESAGE ESTIMATES OF TWO OF LARGE TWO MISTYLARGE GROUPER, MISTY GROUPER, AGE ESTIMATES OF TWO LARGE MISTY GROUPER, EPINEPHELUSEPINEPHELUS MYSTACINUS MYSTACINUS (SERRANIDAE) (SERRANIDAE) FROM BERMUDA FROM BERMUDA EPINEPHELUS MYSTACINUS (SERRANIDAE) FROM BERMUDA WITH A WITHCOMPARISON A COMPARISON OF THE OFAGE THE OF AGETROPICAL OF TROPICAL WITH A COMPARISON OF THE AGE OF TROPICAL GROUPERSGROUPERS IN THE WESTERNIN THE WESTERN ATLANTIC ATLANTIC GROUPERS IN THE WESTERN ATLANTIC Brian E. -

Epinephelus Drummondhayi Goode and Bean, 1878 EED Frequent Synonyms / Misidentifications: None / None

click for previous page 1340 Bony Fishes Epinephelus drummondhayi Goode and Bean, 1878 EED Frequent synonyms / misidentifications: None / None. FAO names: En - Speckled hind; Fr - Mérou grivelé; Sp - Mero pintaroja. Diagnostic characters: Body depth subequal to head length, 2.4 to 2.6 times in standard length (for fish 20 to 43 cm standard length). Nostrils subequal; preopercle rounded, evenly serrate. Gill rakers on first arch 9 or 10 on upper limb, 17 or 18 on lower limb, total 26 to 28. Dorsal fin with 11 spines and 15 or 16 soft rays, the membrane incised between the anterior spines; anal fin with 3 spines and 9 soft rays; caudal fin trun- cate or slightly emarginate, the corners acute; pectoral-fin rays 18. Scales strongly ctenoid, about 125 lateral-scale series; lateral-line scales 72 to 76. Colour: adults (larger than 33 cm) dark reddish brown, densely covered with small pearly white spots; juveniles (less than 20 cm) bright yellow, covered with small bluish white spots. Size: Maximum about 110 cm; maximum weight 30 kg. Habitat, biology, and fisheries: Adults inhabit offshore rocky bottoms in depths of 25 to 183 m but are most common between 60 and 120 m.Females mature at 4 or 5 years of age (total length 45 to 60 cm).Spawning oc- curs from July to September, and a large female may produce up to 2 million eggs at 1 spawning. Back-calculated total lengths for fish aged 1 to 15 years are 19, 32, 41, 48, 53, 57, 61, 65, 68, 71, 74, 77, 81, 84, and 86 cm; the maximum age attained is at least 25 years, and the largest specimen measured was 110 cm. -

Diet Composition of Juvenile Black Grouper (Mycteroperca Bonaci) from Coastal Nursery Areas of the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico

BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE, 77(3): 441–452, 2005 NOTE DIET COMPOSITION OF JUVENILE BLACK GROUPER (MYCTEROPERCA BONACI) FROM COASTAL NURSERY AREAS OF THE YUCATÁN PENINSULA, MEXICO Thierry Brulé, Enrique Puerto-Novelo, Esperanza Pérez-Díaz, and Ximena Renán-Galindo Groupers (Epinephelinae, Epinephelini) are top-level predators that influence the trophic web of coral reef ecosystems (Parrish, 1987; Heemstra and Randall, 1993; Sluka et al., 2001). They are demersal mesocarnivores and stalk and ambush preda- tors that sit and wait for larger moving prey such as fish and mobile invertebrates (Cailliet et al., 1986). Groupers contribute to the ecological balance of complex tropi- cal hard-bottom communities (Sluka et al., 1994), and thus large changes in their populations may significantly alter other community components (Parrish, 1987). The black grouper (Mycteroperca bonaci Poey, 1860) is an important commercial and recreational fin fish resource in the western Atlantic region (Bullock and Smith, 1991; Heemstra and Randall, 1993). The southern Gulf of Mexico grouper fishery is currently considered to be deteriorated and M. bonaci, along with red grouper (Epinephelus morio Valenciennes, 1828) and gag (Mycteroperca microlepis Goode and Bean, 1880), is one of the most heavily exploited fish species in this region (Co- lás-Marrufo et al., 1998; SEMARNAP, 2000). Currently, M. bonaci is considered a threatened species (Morris et al., 2000; IUCN, 2003) and has been classified as vul- nerable in U.S. waters because male biomass in the Atlantic dropped from 20% in 1982 to 6% in 1995 (Musick et al., 2000). The black grouper is usually found on irregular bottoms such as coral reefs, drop- off walls, and rocky ledges, at depths from 10 to 100 m (Roe, 1977; Manooch and Mason, 1987; Bullock and Smith, 1991; Heemstra and Randall, 1993). -

V a Tion & Management of Reef Fish Sp a Wning Aggrega Tions

handbook CONSERVATION & MANAGEMENT OF REEF FISH SPAWNING AGGREGATIONS A Handbook for the Conservation & Management of Reef Fish Spawning Aggregations © Seapics.com Without the Land and the Sea, and their Bounties, the People and their Traditional Ways would be Poor and without Cultural Identity Fijian Proverb Why a Handbook? 1 What are Spawning Aggregations? 2 How to Identify Spawning Aggregations 2 Species that Aggregate to Spawn 2 Contents Places Where Aggregations Form 9 Concern for Spawning Aggregations 10 Importance for Fish and Fishermen 10 Trends in Exploited Aggregations 12 Managing & Conserving Spawning Aggregations 13 Research and Monitoring 13 Management Options 15 What is SCRFA? 16 How can SCRFA Help? 16 SCRFA Work to Date 17 Useful References 18 SCRFA Board of Directors 20 Since 2000, scientists, fishery managers, conservationists and politicians have become increasingly aware, not only that many commercially important coral reef fish species aggregate to spawn (reproduce) but also that these important reproductive gatherings are particularly susceptible to fishing. In extreme cases, when fishing pressure is high, aggregations can dwindle and even cease to form, sometimes within just a few years. Whether or not they will recover and what the long-term effects on the fish population(s) might be of such declines are not yet known. We do know, however, that healthy aggregations tend to be associated with healthy fisheries. It is, therefore, important to understand and better protect this critical part of the life cycle of aggregating species to ensure that they continue to yield food and support livelihoods. Why a Handbook? As fishing technology improved in the second half of the twentieth century, engines came to replace sails and oars, the cash economy developed rapidly, and human populations and demand for seafood grew, the pressures on reef fishes for food, and especially for money, increased enormously. -

Nassau Grouper

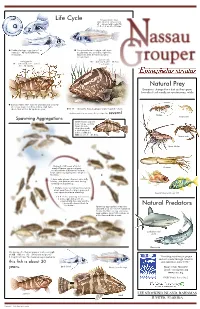

Life Cycle Pelagic juvenile stage (Late larval to early juvenile) 25 ‒ 30 mm total length (TL) (1.0 ‒ 1.2 in) 35 ‒ 50 days Fertilized pelagic eggs (up to 1 mm) Competent larvae ready to settle from hatch 23 ‒ 40 hours following the plankton are carried by night-time fertilization. flood tides from the open ocean to nursery areas. Late juvenile Early juvenile 150 ‒ 400 mm TL (5.9 ‒ 15.7 in) 30 ‒ 150 mm TL (1.9 ‒ 5.9 in) 1 ‒ 4 years 10 ‒ 12 months Natural Prey Groupers change their diet as they grow. Juveniles feed mostly on crustaceans, while Early juveniles settle from the plankton into a variety of nursery areas including inshore algal beds, where they will live for up to one year. At 10 ‒ 12 months Nassau grouper move to patch reefs in shallow-water areas where they remain for several Shrimp Spawning Aggregations Amphipods Some Nassau grouper may change sex from female to male when they reach a total length of between 300 and 800 mm (11.9 ‒ 31.5 in). Spider crab Spiny lobster During the full moon of winter months Nassau grouper migrate Octopus up to hundreds of kilometers to form large spawning aggregations at specific locations. 1. Four color phases - barred, white belly, bicolor, and dark are observed during courtship and spawning. 2. Multiple males and at least one female break away from the larger group and rush upwards prior to spawning. Several species of reef fish 3 & 4. As the spawning rush reaches a peak, eggs and sperm are released into the water and the fish rapidly descend back to the bottom. -

Fish Assemblages Associated with Red Grouper Pits at Pulley Ridge, A

419 Abstract—Red grouper (Epineph- elus morio) modify their habitat by Fish assemblages associated with red grouper excavating sediment to expose rocky pits, providing structurally complex pits at Pulley Ridge, a mesophotic reef in the habitat for many fish species. Sur- Gulf of Mexico veys conducted with remotely op- erated vehicles from 2012 through 2015 were used to characterize fish Stacey L. Harter (contact author)1 assemblages associated with grouper Heather Moe1 pits at Pulley Ridge, a mesophotic 2 coral ecosystem and habitat area John K. Reed of particular concern in the Gulf Andrew W. David1 of Mexico, and to examine whether invasive species of lionfish (Pterois Email address for contact author: [email protected] spp.) have had an effect on these as- semblages. Overall, 208 grouper pits 1 Southeast Fisheries Science Center were examined, and 66 fish species National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA were associated with them. Fish as- 3500 Delwood Beach Road semblages were compared by using Panama City, Florida 32408 several factors but were considered 2 Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute to be significantly different only on Florida Atlantic University the basis of the presence or absence 5600 U.S. 1 North of predator species in their pit (no Fort Pierce, Florida 34946 predators, lionfish only, red grou- per only, or both lionfish and red grouper). The data do not indicate a negative effect from lionfish. Abun- dances of most species were higher in grouper pits that had lionfish, and species diversity was higher in grouper pits with a predator (lion- The red grouper (Epinephelus morio) waters (>70 m) of the shelf edge and fish, red grouper, or both). -

NOI Nassau Grouper

Sent via electronic mail April 6, 2020 Wilbur Ross, Secretary of Commerce Chris Oliver, Assistant Administrator for Fisheries Department of Commerce National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration 1401 Constitution Ave., NW 1315 East-West Highway Washington, DC 20230 Silver Spring, MD 20910 [email protected] [email protected] RE: 60-Day Notice of Intent to Sue Regarding Violations of the Endangered Species Act; Failure to Designate Critical Habitat for the Nassau Grouper (Epinephelus striatus) Dear Mr. Ross and Mr. Oliver: This letter serves as a sixty-day notice of intent to sue the National Marine Fisheries Service (Service) over violations of Section 4 of the Endangered Species Act (Act), 16 U.S.C. § 1531 et seq. This notice is submitted on behalf of the Center for Biological Diversity, WildEarth Guardians, and Miami Waterkeeper. Specifically, the Service has failed to designate critical habitat for Nassau grouper (Epinephelus striatus). Id. §§ 1533(a)(3)(A), 1533(b)(6)(C). The Service’s failure deprives the grouper important protections and puts it at further risk of extinction. This letter is provided pursuant to the 60-day notice requirement of the citizen suit provision of the Act, to the extent that such notice is deemed necessary by a court. Id. § 1540(g). A. The ESA Requires the Service to Designate Critical Habitat for Nassau Grouper In enacting the ESA, Congress recognized that certain species “have been so depleted in numbers that they are in danger of or threatened with extinction.” Id. § 1531(a)(2). Accordingly, a primary purpose of the ESA is “to provide a means whereby the ecosystems upon which endangered species and threatened species depend may be conserved, [and] to provide a program for the conservation of such . -

Mycteroperca Phenax) Life History for the Gulf of Mexico

Summary Table of Scamp, (Mycteroperca phenax) life history for the Gulf of Mexico. Associations and interactions with environmental and habitat variables are listed with citations. Trophic relationships Habitat Associations and Interactions Life Stage Season Location Temp(oC) Salinity(ppt) Oxygen Depth(m) Food Predators Habitat Selection Growth Mortality Production Eggs Spring Offshore Pelagic Citation 1 1 9 Larvae Spring Offshore Pelagic Citation 1 1 9 Early and About 12 to 33 m Inshore hard Late bottoms and reefs Juveniles Citation 11 5,11 Adults Widely distributed 14-28 C 12-189m; most are Predominately Sharks and other Ledges and high- Reach maximum Catch and release on shelf areas of captured at 40-80 fishes; also large fishes relief hard bottoms; size slowly mortality reported Gulf, especially off m crustaceans and prefer complex for scamp taken of Florida cephalopods structures such as from depths Oculina coral reefs greater than 44 m. Repopulation of overfished sites is slow Citation 1,3,5 8 1,8 1,7 5 1,4,5 7 6,10 Scamp, (Mycteroperca phenax) cont. Trophic relationships Habitat Associations and Interactions Life Stage Season Location Temp(oC) Salinity(ppt) Oxygen Depth(m) Food Predators Habitat Selection Growth Mortality Production Spawning Protogynous Absent from 60-100 m Prefer to spawn at Fishing pressure Availability of Adults hermaphrodite; spawning shelf edge habitat may reduce shelf edge, spawn from grounds below of maximum proportion of males especially late Feb. to 8.6 C; most complexity; Oculina in population Oculina, habitat early June in spawning activity formations a key may be important Gulf; April- occurs above spawning habitat factor Aug. -

FAU Institutional Repository

FAU Institutional Repository http://purl.fcla.edu/fau/fauir This paper was submitted by the faculty of FAU’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute. Notice: ©1992 Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami. This manuscript is available at http://www.rsmas.miami.edu/bms and may be cited as: Gilmore, R.G. & Jones, R. S. (1992). Color variation and associated behavior in the epinepheline groupers, Mycteroperca microlepis (Goode and Bean) and M. phenax Jordan and Swain. Bulletin of Marine Science, 51(1), 83-103. BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE, 51(1): 83-103,1992 CORAL REEF PAPER COLOR VARIATION AND ASSOCIATED BEHAVIOR IN THE EPINEPHELINE GROUPERS, MYCTEROPERCA MICROLEPIS (GOODE AND BEAN) AND M. PHENAX JORDAN AND SWAIN R. Grant Gilmore and Robert S. Jones ABSTRACT Color variants and behavior of scamp, Mycteroperca phenax. and gag, M, microlepis, are described from 64 submersible dives made on reef structures at depths between 20 and 100 m off the east coast of Florida from February 1977 to September 1982. These dives yielded 146 h of observations augmented with video and 35 mm photography. Both species display a variety of color phases associated with social behavior. They are expressed in each case by an aggressive, dominant territorial individual which displays to a group of smaller subor- dinates. Social hierarchy is evident in both species, with the alpha individual being a male in the gag and of undetermined sex in the scamp. Although actual spawning was not docu- mented, hierarchical behavior and displays are interpreted as courtship associated with spawn- ing activity. Courtship is further implied based on the similarity of these behaviors to those recorded for a variety of other fishes including serranids. -

A New Species of Diplectanid (Monogenoidea) from Paranthias Colonus (Perciformes, Serranidae) Off Peru

Parasite 2015, 22,11 Ó M. Knoff et al., published by EDP Sciences, 2015 DOI: 10.1051/parasite/2015011 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:5672579C-3070-4368-8CD0-4EC18D2C01C5 Available online at: www.parasite-journal.org RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS A new species of diplectanid (Monogenoidea) from Paranthias colonus (Perciformes, Serranidae) off Peru Marcelo Knoff1, Simone Chinicz Cohen2,*, Melissa Querido Cárdenas2, Jorge M. Cárdenas-Callirgos3, and Delir Corrêa Gomes1 1 Laboratório de Helmintos Parasitos de Vertebrados, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, FIOCRUZ, Av. Brasil, 4365 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil 2 Laboratório de Helmintos Parasitos de Peixes, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, FIOCRUZ, Av. Brasil, 4365 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil 3 Museo de Historia Natural, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Ricardo Palma (URP), Av. Benavides 54440, Lima 33, Peru Received 30 October 2014, Accepted 23 February 2015, Published online 9 March 2015 Abstract – Pseudorhabdosynochus jeanloui n. sp. (Monogenoidea, Diplectanidae) is described from specimens collected from the gills of the Pacific creolefish, Paranthias colonus (Perciformes, Serranidae) from a fish market in Chorrillos, Lima, Peru. The new species is differentiated from other members of the genus by the structure of its sclerotized vagina, which has two spherical chambers of similar diameter. This is the first Pseudorhabdosynochus species described from the Pacific coast of America, the third species of the genus reported from South America and the first described from a member of Paranthias. Key words: Pseudorhabdosynochus jeanloui n. sp., Monogenea, Diplectanidae, Paranthias colonus, Fish. Résumé – Une nouvelle espèce de Diplectanidae (Monogenoidea) chez Paranthias colonus (Perciformes, Serranidae) au Pérou. Pseudorhabdosynochus jeanloui n. sp. (Monogenoidea, Diplectanidae) est décrit de spécimens collectés sur les branchies de la badèche du Pacifique, Paranthias colonus (Perciformes, Serranidae) d’un marché aux poissons de Chorrillos à Lima au Pérou. -

Snapper and Grouper: SFP Fisheries Sustainability Overview 2015

Snapper and Grouper: SFP Fisheries Sustainability Overview 2015 Snapper and Grouper: SFP Fisheries Sustainability Overview 2015 Snapper and Grouper: SFP Fisheries Sustainability Overview 2015 Patrícia Amorim | Fishery Analyst, Systems Division | [email protected] Megan Westmeyer | Fishery Analyst, Strategy Communications and Analyze Division | [email protected] CITATION Amorim, P. and M. Westmeyer. 2016. Snapper and Grouper: SFP Fisheries Sustainability Overview 2015. Sustainable Fisheries Partnership Foundation. 18 pp. Available from www.fishsource.com. PHOTO CREDITS left: Image courtesy of Pedro Veiga (Pedro Veiga Photography) right: Image courtesy of Pedro Veiga (Pedro Veiga Photography) © Sustainable Fisheries Partnership February 2016 KEYWORDS Developing countries, FAO, fisheries, grouper, improvements, seafood sector, small-scale fisheries, snapper, sustainability www.sustainablefish.org i Snapper and Grouper: SFP Fisheries Sustainability Overview 2015 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The goal of this report is to provide a brief overview of the current status and trends of the snapper and grouper seafood sector, as well as to identify the main gaps of knowledge and highlight areas where improvements are critical to ensure long-term sustainability. Snapper and grouper are important fishery resources with great commercial value for exporters to major international markets. The fisheries also support the livelihoods and food security of many local, small-scale fishing communities worldwide. It is therefore all the more critical that management of these fisheries improves, thus ensuring this important resource will remain available to provide both food and income. Landings of snapper and grouper have been steadily increasing: in the 1950s, total landings were about 50,000 tonnes, but they had grown to more than 612,000 tonnes by 2013.