Unseen Cinema: an Interview with Bruce Posner 1/1/08 9:24 PM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

* Hc Omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1

* hc omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1 Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination: Set Design in 1930s European Cinema presents for the first time a comparative study of European film set design in HARRIS AND STREET BERGFELDER, IMAGINATION FILM ARCHITECTURE AND THE TRANSNATIONAL the late 1920s and 1930s. Based on a wealth of designers' drawings, film stills and archival documents, the book FILM FILM offers a new insight into the development and signifi- cance of transnational artistic collaboration during this CULTURE CULTURE period. IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION European cinema from the late 1920s to the late 1930s was famous for its attention to detail in terms of set design and visual effect. Focusing on developments in Britain, France, and Germany, this book provides a comprehensive analysis of the practices, styles, and function of cine- matic production design during this period, and its influence on subsequent filmmaking patterns. Tim Bergfelder is Professor of Film at the University of Southampton. He is the author of International Adventures (2005), and co- editor of The German Cinema Book (2002) and The Titanic in Myth and Memory (2004). Sarah Street is Professor of Film at the Uni- versity of Bristol. She is the author of British Cinema in Documents (2000), Transatlantic Crossings: British Feature Films in the USA (2002) and Black Narcis- sus (2004). Sue Harris is Reader in French cinema at Queen Mary, University of London. She is the author of Bertrand Blier (2001) and co-editor of France in Focus: Film -

Art and Technology Between the Usa and the Ussr, 1926 to 1933

THE AMERIKA MACHINE: ART AND TECHNOLOGY BETWEEN THE USA AND THE USSR, 1926 TO 1933. BARNABY EMMETT HARAN PHD THESIS 2008 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF ART UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR ANDREW HEMINGWAY UMI Number: U591491 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591491 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Bamaby Emmett Haran, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 ABSTRACT This thesis concerns the meeting of art and technology in the cultural arena of the American avant-garde during the late 1920s and early 1930s. It assesses the impact of Russian technological Modernism, especially Constructivism, in the United States, chiefly in New York where it was disseminated, mimicked, and redefined. It is based on the paradox that Americans travelling to Europe and Russia on cultural pilgrimages to escape America were greeted with ‘Amerikanismus’ and ‘Amerikanizm’, where America represented the vanguard of technological modernity. -

To Visual Structure in Film and Digital Media Collusion with the Russians? Collusion Collusion Collusion

THE ORIGINS OF AND AN INTRODUCTION TO VISUAL STRUCTURE IN FILM AND DIGITAL MEDIA COLLUSION WITH THE RUSSIANS? COLLUSION COLLUSION COLLUSION YES! ABSOLUTELY. But it’s not what you think… Chapter 1 - Origins SOME FOUNDING FATHERS OF VISUAL STRUCTURE SOVIET FILMMAKERS & THEORISTS Forging the Foundations of Visual Structure Lev Kuleshov b. January 13,1899, Tambov, Tsarist Russia d. March 29, 1970, Moscow, USSR For Luck (1917) - Director Na kranson fronte (On the Red Front), (1920) - Director The Death Ray (1925) - Director Contributions to Film Theory & Filmmaking Pavlovian Physiology (the Kuleshov Effect) Creative Geography Instructor, The Moscow Film School (1st one) Cinema as an Artform – Montage is the key The Kuleshov Effect 1920 This video clip does not play in PDF format. SOVIET FILMMAKERS & THEORISTS Forging the Foundations of Visual Structure Sergei Eisenstein b. January 23,1898, Riga, Latvia d. February 11, 1948, Moscow, USSR Strike! (1924) - Director Battleship Potemkin (1925) - Director Alexander Nevsky (1938) - Director Contributions to Film Theory & Filmmaking Montage : Metric, Rhythmic, Tonal, Overtonal, Intellectual Dialectics by means of Cinema Editing Techniques based on Biomechanics Cinema as Vehicle for Struggle SOVIET FILMMAKERS & THEORISTS Forging the Foundations of Visual Structure Vsevolod Pudovkin b. February 16, 1893, Penza, Russia d. June 30, 1953, Jurmala, Latvia Chess Fever (1925) - Director Mother (1926) – Director (His Masterpiece) Storm Over Asia (1928) - Director Contributions to Film Theory & Filmmaking His Book: Film Technique and Film Acting, 1954. Plastic Synthesis – Editing over Acting, & Typage 5 editing techniques: Contrast, Parallelism, Symbolism, Simultaneity, and Leit Motif (a short, constantly recurring musical phrase) The Kuleshov Effect 2011 Shame – Dir. Steve McQueen, Editor – Joe Walker SOVIET FILMMAKERS & THEORISTS Forging the Foundations of Visual Structure Alexander Dovzhenko (Ukraine) b. -

On the Meaning of a Cut : Towards a Theory of Editing

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output On the meaning of a cut : towards a theory of editing https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40391/ Version: Full Version Citation: Dziadosz, Bartłomiej (2019) On the meaning of a cut : towards a theory of editing. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email ON THE MEANING OF A CUT: TOWARDS A THEORY OF EDITING Bartłomiej Dziadosz A dissertation submitted to the Department of English and Humanities in candidacy for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Birkbeck, University of London October 2018 Abstract I confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own and the work of other persons is appropriately acknowledged. This thesis looks at a variety of discourses about film editing in order to explore the possibility, on the one hand, of drawing connections between them, and on the other, of addressing some of their problematic aspects. Some forms of fragmentation existed from the very beginnings of the history of the moving image, and the thesis argues that forms of editorial control were executed by early exhibitors, film pioneers, writers, and directors, as well as by a fully- fledged film editor. This historical reconstruction of how the profession of editor evolved sheds light on the specific aspects of their work. Following on from that, it is proposed that models of editing fall under two broad paradigms: of montage and continuity. -

Hollywood-Montage. Theorie, Geschichte Und Analyse Des «Vorkapich-Effekts» 2016

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Patrick Vonderau Hollywood-Montage. Theorie, Geschichte und Analyse des «Vorkapich-Effekts» 2016 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/13003 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Vonderau, Patrick: Hollywood-Montage. Theorie, Geschichte und Analyse des «Vorkapich-Effekts». In: montage AV. Zeitschrift für Theorie und Geschichte audiovisueller Kommunikation. 1992, Jg. 25 (2016), Nr. 2, S. 201– 224. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/13003. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://www.montage-av.de/pdf/2016_25_2_MontageAV/montageav16-2-Vonderau.pdf Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under a Deposit License (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, non-transferable, individual, and limited right for using this persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses document. This document is solely intended for your personal, Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für non-commercial use. All copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute, or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the conditions of vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder use stated above. -

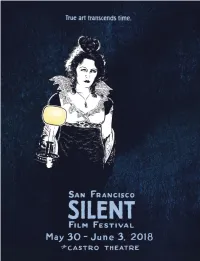

SFSFF 2018 Program Book

elcome to the San Francisco Silent Film Festival for five days and nights of live cinema! This is SFSFFʼs twenty-third year of sharing revered silent-era Wmasterpieces and newly revived discoveries as they were meant to be experienced—with live musical accompaniment. We’ve even added a day, so there’s more to enjoy of the silent-era’s treasures, including features from nine countries and inventive experiments from cinema’s early days and the height of the avant-garde. A nonprofit organization, SFSFF is committed to educating the public about silent-era cinema as a valuable historical and cultural record as well as an art form with enduring relevance. In a remarkably short time after the birth of moving pictures, filmmakers developed all the techniques that make cinema the powerful medium it is today— everything except for the ability to marry sound to the film print. Yet these films can be breathtakingly modern. They have influenced every subsequent generation of filmmakers and they continue to astonish and delight audiences a century after they were made. SFSFF also carries on silent cinemaʼs live music tradition, screening these films with accompaniment by the worldʼs foremost practitioners of putting live sound to the picture. Showcasing silent-era titles, often in restored or preserved prints, SFSFF has long supported film preservation through the Silent Film Festival Preservation Fund. In addition, over time, we have expanded our participation in major film restoration projects, premiering four features and some newly discovered documentary footage at this event alone. This year coincides with a milestone birthday of film scholar extraordinaire Kevin Brownlow, whom we celebrate with an onstage appearance on June 2. -

The American Film Institute and Philanthropic Support For

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository@Napier “IN THE BEST INTERESTS OF THE COUNTRY”: THE AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE AND PHILANTHROPIC SUPPORT FOR AMERICAN EXPERIMENTAL AND INDEPENDENT CINEMA IN THE 1960s. BY R CI R RE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR IN PHILOSOPHY AT EDINBURGH NAPIER UNIVERSITY APRIL 2013 ii Contents Tables ........................................................................................................................ vi Figures ....................................................................................................................... vi Acknowledgements .................................................................................................. vii Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... viii Abstract ..................................................................................................................... ix INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 Defining Experimental and Independent Cinema ....................................................... 2 Personal Films and the Medium-Specific Evolution of Avant-Garde Cinema ........... 6 Philanthropic Support and Avant-Garde Arts ........................................................... 12 Experimental Cinema in Academic Institutions ...................................................... -

Experiment in the Film

sh. eitedbyM&l MANVOX EXPERIMENT IN THE FILM edited by Roger Manveil In all walks of life experiment precedes and paves the way for practical and widespread development. The Film is no exception, yet although it must be considered one of the most popular forms of entertainment, very little is known by the general public about its experimental side. This book is a collec- tion of essays by the leading experts of all countries on the subject, and it is designed to give a picture of the growth and development of experiment in the Film. Dr. Roger Manvell, author of the Penguin book Film, has edited the collection and contributed a general appreciation. Jacket design by William Henry 15s. Od. net K 37417 NilesBlvd S532n 510-494-1411 Fremont CA 94536 www.nilesfilminiiseuin.org Scanned from the collections of Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum Coordinated by the Media History Digital Library www.mediahistoryproject.org Funded by a donation from Jeff Joseph EDITED BY ROGER MANVELL THE GREY WALLS PRESS LTD First published in 1949 by the Grey Walls Press Limited 7 Crown Passage, Pall Mall, London S.W.I Printed in Great Britain by Balding & Mansell Limited London All rights reserved AUSTRALIA The Invincible Press Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide NEW ZEALAND The Invincible Press, Wellington SOUTH AFRICA M. Darling (Pty.) Ltd., Capetown EDITOR'S FOREWORD The aim of this book is quite simply to gather together the views of a number of people, prominent either in the field of film-making or film-criticism or in both, on the contribution of their country to the experimental development of the film. -

By Slavki Vorkapich

he Museum of Modern Art No, 9k • (Vest 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart pQp IMMEDIATE RELEASE F*&3&y, -Dacenber 11, .196^ LECTURES ON THE FILM: THE VISUAL NATURE OF THE FILM MEDIUM BY SLAVKO VORKAPICH Ten illustrated lecture-seminars on the nature of the film will be given by Slavko Vorkapich at The Museum of Modern Art on Monday evenings, from 8 to 10 p.m., beginning February 1 and running through April 5, 1965• Although the series is designed for professional and student film-makers, it will be open to the public. The program will include the following lectures: INTRODUCTION: THE EYE HAS ITS REASONS. Laws of visual perception. BIPOLAR ORGANIZATION. The force of offscreen directed attention. THE GESTALT LAW OF "GOOD CONTINUATION." Movement from shot to shot. OBJECT-MOTION ("REAL MOTION") AND THE STATIONARY CAMERA. TO HOLD, AS'T WERE, A MOVING MIRROR UP TO NATURE. Camera movement. ANGLES, LOW AND HIGH, AS VARIABLES OF SHOOTING. ANOTHER VARIABLE: VIEWER'S DISTANCE FROM THE SCREEN. TRICKS AS TRICKS AND AS LEGITIMATE FILMIC DEVICES. ESTHETICS OF FILM FORM ESTHETICS OF FILM CONTENT. More than fifty excerpts from the work of such historic and contemporary film makers as Antonioni, Cocteau, Eisenstein, Fellini, Flaherty, Godard, Griffith, Kubrick, Kurosawa, Murnau, Renoir, Resnais, Ruttman, de Sica, Truffaut, Van Dyke, Welles, Wise, and Zinnemann will be screened during the lectures. Slavko Vorkapich, who has been making films in Hollywood since the late 20s, was born in Yugoslavia in 1895 and educated in Belgrade, Budapest and Paris. He came to the United States in 1920. -

Expanded Cinema

EXPANDED CINEMA ARTSCILAB 2001 2 Blank Page ARTSCILAB 2001 Gene Youngblood became a passenger of Spaceship Earth on May 30, 1942. He is a faculty member of the California Institute of the Arts, School of Critical Studies. Since 1961 he has worked in all aspects of communications media: for five years he was reporter, feature writer, and film critic for the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner; in 1965 he conducted a weekly program on film and the arts for KPFK, Pacifica Radio in Los Angeles; in 1967 he wrote, produced, directed, edited, and on-camera reported "human interest" filmed news features for KHJ-TV in Los Angeles; since 1967 his column “Intermedia” has appeared weekly in the Los Angeles Free Press on subjects ranging from film and the arts to science, technology, and the cultural revolution. Mr. Youngblood currently is working on two books: The Videosphere, about global television in the 1970s as a tool for conscious evolution, and Earth Nova, a philosophical novel and screenplay about the new consciousness, the new lifestyle, and their relation to technology. ARTSCILAB 2001 4 Blank Page ARTSCILAB 2001 EXPANDED CINEMA by Gene Youngblood Introduction by R. Buckminster Fuller A Dutton Paperback P. Dutton & Co., Inc., New York 1970 ARTSCILAB 2001 Copyright © 1970 by Gene Youngblood Introduction and poem, "Inexorable Evolution and Human Ecology," copyright © 1970 by R. Buckminster Fuller All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. First Edition No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publishers, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine or newspaper or broadcast. -

Film Terms Glossary Cinematic Terms Definition and Explanation Example (If Applicable) 180 Degree Rule a Screen Direction Rule T

Film Terms Glossary Cinematic Terms Definition and Explanation Example (if applicable) a screen direction rule that camera operators must follow - Camera placement an imaginary line on one side of the axis of action is made must adhere to the (e.g., between two principal actors in a scene), and the 180 degree rule 180 degree rule camera must not cross over that line - otherwise, there is a distressing visual discontinuity and disorientation; similar to the axis of action (an imaginary line that separates the camera from the action before it) that should not be crossed Example: at 24 fps, 4 refers to the standard frame rate or film speed - the number projected frames take 1/6 of frames or images that are projected or displayed per second to view second; in the silent era before a standard was set, many 24 frames per second films were projected at 16 or 18 frames per second, but that rate proved to be too slow when attempting to record optical film sound tracks; aka 24fps or 24p Examples: the first major 3D feature film was Bwana Devil (1953) [the first a film that has a three-dimensional, stereoscopic form or was Power of Love (1922)], House of Wax appearance, giving the life-like illusion of depth; often (1953), Cat Women of the Moon (1953), the achieved by viewers donning special red/blue (or green) or MGM musicalKiss Me Kate polarized lens glasses; when 3-D images are made (1953), Warner's Hondo (1953), House of 3-D interactive so that users feel involved with the scene, the Wax (1953), a version of Hitchcock's Dial M experience is -

Displaced Film Memories in the Post- Yugoslav Context Research Article

Displaced Film Memories in the post- Yugoslav Context Research Article Sanjin Pejković PhD candidate in Film studies, Lund University [email protected] Contemporary Southeastern Europe, 2017, 4(2), 89-101 DOI 10.25364/02.4:2017.2.6 Contemporary Southeastern Europe is an online, peer-reviewed, multidisciplinary journal that publishes original, scholarly, and policy-oriented research on issues relevant to societies in Southeastern Europe. For more information, please contact us at [email protected] or visit our website at www.contemporarysee.org Displaced Film Memories in the post- Yugoslav Context Sanjin Pejković In this article, I will try to discern a few different stylistic and thematic approaches of memory representation of the former Yugoslavia in the post- Yugoslav context. I will focus on notions of displaced mediated memories that we get from documentary films of the once existing country. A lot has been written on filmic aspects of remembrance in the post-Yugoslav area, the so-called Yugosphere, but not that many studies have concentrated on mediated memories of the diasporic groups outside the area that once constituted Yugoslavia. In order to talk about displaced memories of the former Yugoslavia, I need to establish some ideas of displaced filmmaking, memory conveying and representations of history. I will also present a general scheme of connections between documentary filmmaking and memories in the area of the former federation, and then concentrate on what I perceive to be three different standpoints on filmic remembrances outside the region. Kewords: film, memory, Yugoslavia, diaspora Introduction The fall of Yugoslavia was a historical event of huge importance for the Balkans, Europe and the world.