Displaced Film Memories in the Post- Yugoslav Context Research Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

485 Svilicic.Vp

Coll. Antropol. 37 (2013) 4: 1327–1338 Original scientific paper The Popularization of the Ethnological Documentary Film at the Beginning of the 21st Century Nik{a Svili~i}1 and Zlatko Vida~kovi}2 1 Institute for Anthropological Research, Zagreb, Croatia 2 University of Zagreb, Academy of Dramatic Art, Zagreb, Croatia ABSTRACT This paper seeks to explain the reasons for the rising popularity of the ethnological documentary genre in all its forms, emphasizing its correlation with contemporary social events or trends. The paper presents the origins and the de- velopment of the ethnological documentary film in the anthropological domain. Special attention is given to the most in- fluential documentaries of the last decade, dealing with politics: (Fahrenheit 9/1, Bush’s Brain), gun control (Bowling for Columbine), health (Sicko), the economy (Capitalism: A Love Story), ecology An Inconvenient Truth) and food (Super Size Me). The paper further analyzes the popularization of the documentary film in Croatia, the most watched Croatian documentaries in theatres, and the most controversial Croatian documentaries. It determines the structure and methods in the making of a documentary film, presents the basic types of scripts for a documentary film, and points out the differ- ences between scripts for a documentary and a feature film. Finally, the paper questions the possibility of capturing the whole truth and whether some documentaries, such as the Croatian classics: A Little Village Performance and Green Love, are documentaries at all. Key words: documentary film, anthropological topics, script, ethnographic film, methods, production, Croatian doc- umentaries Introduction This paper deals with the phenomenon of the popu- the same time, creating a work of art. -

* Hc Omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1

* hc omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1 Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination: Set Design in 1930s European Cinema presents for the first time a comparative study of European film set design in HARRIS AND STREET BERGFELDER, IMAGINATION FILM ARCHITECTURE AND THE TRANSNATIONAL the late 1920s and 1930s. Based on a wealth of designers' drawings, film stills and archival documents, the book FILM FILM offers a new insight into the development and signifi- cance of transnational artistic collaboration during this CULTURE CULTURE period. IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION European cinema from the late 1920s to the late 1930s was famous for its attention to detail in terms of set design and visual effect. Focusing on developments in Britain, France, and Germany, this book provides a comprehensive analysis of the practices, styles, and function of cine- matic production design during this period, and its influence on subsequent filmmaking patterns. Tim Bergfelder is Professor of Film at the University of Southampton. He is the author of International Adventures (2005), and co- editor of The German Cinema Book (2002) and The Titanic in Myth and Memory (2004). Sarah Street is Professor of Film at the Uni- versity of Bristol. She is the author of British Cinema in Documents (2000), Transatlantic Crossings: British Feature Films in the USA (2002) and Black Narcis- sus (2004). Sue Harris is Reader in French cinema at Queen Mary, University of London. She is the author of Bertrand Blier (2001) and co-editor of France in Focus: Film -

Art and Technology Between the Usa and the Ussr, 1926 to 1933

THE AMERIKA MACHINE: ART AND TECHNOLOGY BETWEEN THE USA AND THE USSR, 1926 TO 1933. BARNABY EMMETT HARAN PHD THESIS 2008 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF ART UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR ANDREW HEMINGWAY UMI Number: U591491 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591491 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Bamaby Emmett Haran, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 ABSTRACT This thesis concerns the meeting of art and technology in the cultural arena of the American avant-garde during the late 1920s and early 1930s. It assesses the impact of Russian technological Modernism, especially Constructivism, in the United States, chiefly in New York where it was disseminated, mimicked, and redefined. It is based on the paradox that Americans travelling to Europe and Russia on cultural pilgrimages to escape America were greeted with ‘Amerikanismus’ and ‘Amerikanizm’, where America represented the vanguard of technological modernity. -

GLAZBA I POP KULTURA 80-Ih U JUGOSLAVIJI

GLAZBA I POP KULTURA 80-ih U JUGOSLAVIJI Periša, Antonija Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2018 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Academy of Arts and Culture in Osijek / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Akademija za umjetnost i kulturu u Osijeku Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:251:309501 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-23 Repository / Repozitorij: Repository of the Academy of Arts and Culture in Osijek Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku Akademija za umjetnost i kulturu Preddiplomski studij Kulturalni menadžment Antonija Periša GLAZBA I POP KULTURA 80-ih U JUGOSLAVIJI Završni rad Osijek, 2018. Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku Akademija za umjetnost i kulturu Preddiplomski studij Kulturalni menadžment Antonija Periša GLAZBA I POP KULTURA 80-ih U JUGOSLAVIJI Završni rad Kolegij: Povijest hrvatske kulture 2 JMBAG: 601983 11 0344002506 3 e-mail: [email protected] Mentor: doc.dr.sc. Vladimir Rismondo Osijek, 2018. Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek Academy of Arts Undergraduate Study of cultural management Antonija Periša MUSIC AND POP CULTURE OF THE 80s IN YUGOSLAVIA Final paper Osijek, 2018. Sažetak Popularna kultura se može definirati na nekoliko različitih načina, ovisno o razdoblju, pogledu na kulturu i o nizu drugih čimbenika. Najbolje se može opisati kao kultura koja je dostupna svima i koja je široko rasprostranjena te je najzastupljenija u masovnim medijima kao što su film, glazba, televizija, šport i slično. Ona može biti opisana kao nešto što je trenutno moderno, kao nešto što ljudi trenutno vole, slušaju, čitaju te se upravo zbog te činjenice ne može svrstati u samo jedno razdoblje hrvatske povijesti niti u jedno razdoblje općenito. -

239 Postanak I Razvoj Novog Vala Na Području Bivše

POSAAK AZVOJ NOVO ALA NA PODRUČJU BIVŠE JUGOSLAVIJE Filozofski fakultet u Splitu, Odsjek za povijest E-mail: [email protected] Mihaljević Jurković Novi val vrsta je glazbe koja se pojavila u Velikoj Britaniji i u SAD-u 70-ih godina prošlog stoljeća. Iako prisutan već od druge polovice 70-ih, novi će val potaknuti veličanstveni uzlet bendova poklonika tog žanra, kao što su Azra, Prljavo kazalište, Film, Haustor na hrvatskoj, odnosno Električni orgazam, Šarlo akrobata i Idoli na srpskoj sceni. Ti su ljudi kreirali novu i drugačiju povijest, novu i drugačiju supkulturu koja je nesumnjivo utjecala na mlade generacije onog vremena. Prodor novog žanra u komunističke je zemlje, zbog njihove izoliranosti od zapadnih modernih utjecaja bio otežan, u nekim gotovo i nemoguć. Koji je to bitni element ili koji su to bitni elementi koji su otvorili vrata Jugoslavije Zapadu unatoč njezinoj orijentaciji? U kakvim se političkim prilikama razvijao i koliko je područja obuhvatio, odnosno je li se odnosio samo i isključivo na glazbu? Naposljetku, ne možemo se ne zapitati, upoznati sa situacijom na istoku i centru Europe, zašto je jedan tvrdokorni komunistički režim tolerirao buntovnost, samoizražavanje i slobodu rocka. Ovaj članak problematizira navedenu tematiku. Ključne riječi: novi val, 80-e, Jugoslavija, Polet, Azra, Pankrti, Prljavo kazalište, Branimir Štulić Johnny, Darko Rundek, Haustor, Bijelo dugme, Laibach Povijest noo aa Novi val u francuskoj kinematografiji s kraja 0- sineastima, nije se od samih početaka odnosio na glazbu. Naime, taj je pojam bio poznat novi val ih godina prošlog stoljeća po mladim dru odnosno mladim inovativnim predstavnicima umjetnosti. Osim što je zaslužan za gačije shvaćanje francuske kinematografije u smislu ideja o efikasnijoj i jeftinijoj glazbi.647 proizvodnji i metodama, dao je poticaj promjenama u drugim umjetnostima, naročito u Tijekom kasnih 70-ih i ranih 0- novog vala punka i rocka. -

To Visual Structure in Film and Digital Media Collusion with the Russians? Collusion Collusion Collusion

THE ORIGINS OF AND AN INTRODUCTION TO VISUAL STRUCTURE IN FILM AND DIGITAL MEDIA COLLUSION WITH THE RUSSIANS? COLLUSION COLLUSION COLLUSION YES! ABSOLUTELY. But it’s not what you think… Chapter 1 - Origins SOME FOUNDING FATHERS OF VISUAL STRUCTURE SOVIET FILMMAKERS & THEORISTS Forging the Foundations of Visual Structure Lev Kuleshov b. January 13,1899, Tambov, Tsarist Russia d. March 29, 1970, Moscow, USSR For Luck (1917) - Director Na kranson fronte (On the Red Front), (1920) - Director The Death Ray (1925) - Director Contributions to Film Theory & Filmmaking Pavlovian Physiology (the Kuleshov Effect) Creative Geography Instructor, The Moscow Film School (1st one) Cinema as an Artform – Montage is the key The Kuleshov Effect 1920 This video clip does not play in PDF format. SOVIET FILMMAKERS & THEORISTS Forging the Foundations of Visual Structure Sergei Eisenstein b. January 23,1898, Riga, Latvia d. February 11, 1948, Moscow, USSR Strike! (1924) - Director Battleship Potemkin (1925) - Director Alexander Nevsky (1938) - Director Contributions to Film Theory & Filmmaking Montage : Metric, Rhythmic, Tonal, Overtonal, Intellectual Dialectics by means of Cinema Editing Techniques based on Biomechanics Cinema as Vehicle for Struggle SOVIET FILMMAKERS & THEORISTS Forging the Foundations of Visual Structure Vsevolod Pudovkin b. February 16, 1893, Penza, Russia d. June 30, 1953, Jurmala, Latvia Chess Fever (1925) - Director Mother (1926) – Director (His Masterpiece) Storm Over Asia (1928) - Director Contributions to Film Theory & Filmmaking His Book: Film Technique and Film Acting, 1954. Plastic Synthesis – Editing over Acting, & Typage 5 editing techniques: Contrast, Parallelism, Symbolism, Simultaneity, and Leit Motif (a short, constantly recurring musical phrase) The Kuleshov Effect 2011 Shame – Dir. Steve McQueen, Editor – Joe Walker SOVIET FILMMAKERS & THEORISTS Forging the Foundations of Visual Structure Alexander Dovzhenko (Ukraine) b. -

Novi Val U Glazbi Kao Odgovor Na Društveno-Politiĉke Promjene U Jugoslaviji 1980-Ih Godina

Sveuĉilište u Zagrebu Filozofski fakultet Odsjek za povijest DIPLOMSKI RAD Tema: Novi val u glazbi kao odgovor na društveno-politiĉke promjene u Jugoslaviji 1980-ih godina Student: Nino Mihaljek Mentor: Hrvoje Klasić, dr. sc. Vlastoruĉni potpis: U Zagrebu, rujan 2015. _________________ SADRŢAJ 1. UVOD……………………………………………………………………………….3 2. ZAHVALE……………………………………………………………….................4 3. DRUŠTVENO-POLITIĈKA SITUACIJA U JUGOSLAVIJI KRAJEM 70-IH GODINA…………………………………………………………………….5 4. OBILJEŢJA PUNK GLAZBE…………………………………………………. 10 5. VAŢNOST BIJELOG DUGMETA ZA RAZVOJ DOMAĆE ROCK GLAZBE………………………………………………………………………….. 12 6. POJAVA PRVE JUGOSLAVENSKE ALTERNATIVNE GRUPE – BULDOŢER……………………………………………………………………… 14 7. RAZVOJ JUGOSLAVENSKOG PUNKA……………………………………....17 7.1. Pojava Pankrta i stvaranje ljubljanske punk scene……………………………17 7.2. Razvoj riječke punk scene – Paraf i Termiti…………………………………...23 7.3. Prljavo kazalište i formiranje zagrebačke punk scene………………………...32 8. FORMIRANJE ZAGREBAĈKE NOVOVALNE SCENE……………………..40 8.1. Azra…………………………………………………………………………….40 8.2. Film i Haustor………………………………………………………………….48 9. POJAVA I RAZVOJ BEOGRADSKOG NOVOG TALASA………………….53 10. BEOGRADSKI NOVOTALASNI BENDOVI………………………………....57 10.1. Električni orgazam…………………………………………………………...57 10.2. Idoli…………………………………………………………………………...61 11. ZAKLJUĈAK……………………………………………………………………65 12. SAŢETAK………………………………………………………………………. 67 13. BIBLIOGRAFIJA……………………………………………………………….68 2 1.Uvod IzmeĊu druge polovice 70-ih i sredine 80-ih godina 20. stoljeća, u Jugoslaviji se, pod utjecajem svjetskih dogaĊanja, -

Vizualni Identitet Glazbene Produkcije Novoga Vala (1977

Sveučilište u Zagrebu Filozofski fakultet Odsjek za povijest umjetnosti Vizualni identitet glazbene produkcije novoga vala (1977. - 1987.) Diplomski rad mentor: dr. sc. Frano Dulibić, red. prof. studentica: Kora Girin Zagreb, 2016. Sadržaj 1. Uvod........................................................................................................................................3 1. 1. Problem definicije i periodizacije glazbenoga žanra novoga vala ............................... 3 1.2. Pitanje novovalnoga senzibiliteta ................................................................................... 8 1.3. Novi val i postmodernizam...........................................................................................13 1.4. Glazbeni spot i televizija kao arhetipske postmodernističke forme. Primjeri novovalnih glazbenih spotova......................................................................................................................15 1.5. Grafički dizajn i postmodernistička estetika ................................................................ 21 2. Punk......................................................................................................................................23 2.1. Punk i vizualni identitet punka u svijetu.......................................................................23 2.2.Punk u Jugoslaviji ......................................................................................................... 26 2.3.Vizualni identitet slovenskoga punka .......................................................................... -

On the Meaning of a Cut : Towards a Theory of Editing

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output On the meaning of a cut : towards a theory of editing https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40391/ Version: Full Version Citation: Dziadosz, Bartłomiej (2019) On the meaning of a cut : towards a theory of editing. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email ON THE MEANING OF A CUT: TOWARDS A THEORY OF EDITING Bartłomiej Dziadosz A dissertation submitted to the Department of English and Humanities in candidacy for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Birkbeck, University of London October 2018 Abstract I confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own and the work of other persons is appropriately acknowledged. This thesis looks at a variety of discourses about film editing in order to explore the possibility, on the one hand, of drawing connections between them, and on the other, of addressing some of their problematic aspects. Some forms of fragmentation existed from the very beginnings of the history of the moving image, and the thesis argues that forms of editorial control were executed by early exhibitors, film pioneers, writers, and directors, as well as by a fully- fledged film editor. This historical reconstruction of how the profession of editor evolved sheds light on the specific aspects of their work. Following on from that, it is proposed that models of editing fall under two broad paradigms: of montage and continuity. -

Theorising Return Migration

MAX WEBER PROGRAMME EUI Working Papers MWP 2011/20 MAX WEBER PROGRAMME THE SILENT REPUBLIC: POPULAR MUSIC AND NATIONALISM IN SOCIALIST CROATIA Dean Vuletic EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE MAX WEBER PROGRAMME The Silent Republic: Popular Music and Nationalism in Socialist Croatia DEAN VULETIC EUI Working Paper MWP 2011/20 This text may be downloaded for personal research purposes only. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper or other series, the year, and the publisher. ISSN 1830-7728 © 2011 Dean Vuletic Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Abstract This paper explores the development of popular music and its relationship to the political situation in Croatia and Yugoslavia from 1945 to 1991, and how global musical trends were used to construct and reinvent Croatian and Yugoslav cultural and political identities. It begins with a discussion of the suppression of patriotic music in the early decades of socialist Yugoslavia, when the regime attempted to create a supranational culture that would unify Yugoslavia’s constituent nations. It then analyses the national cultural revival in Croatia in the late 1960s that prompted a political movement known as the Croatian Spring, when the pop singer Vice Vukov incorporated Croatian patriotic themes into his songs. In the years following the crushing of the Croatian Spring in 1971, Croatian nationalism was again suppressed in politics and music, and because of this stifling of political opposition Croatia was dubbed “the silent republic.” For the rest of the 1970s the political function of pop and rock music was reflected in its glorification of Yugoslavia and its leader, Josip Broz Tito. -

Hollywood-Montage. Theorie, Geschichte Und Analyse Des «Vorkapich-Effekts» 2016

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Patrick Vonderau Hollywood-Montage. Theorie, Geschichte und Analyse des «Vorkapich-Effekts» 2016 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/13003 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Vonderau, Patrick: Hollywood-Montage. Theorie, Geschichte und Analyse des «Vorkapich-Effekts». In: montage AV. Zeitschrift für Theorie und Geschichte audiovisueller Kommunikation. 1992, Jg. 25 (2016), Nr. 2, S. 201– 224. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/13003. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://www.montage-av.de/pdf/2016_25_2_MontageAV/montageav16-2-Vonderau.pdf Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under a Deposit License (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, non-transferable, individual, and limited right for using this persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses document. This document is solely intended for your personal, Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für non-commercial use. All copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute, or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the conditions of vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder use stated above. -

SFSFF 2018 Program Book

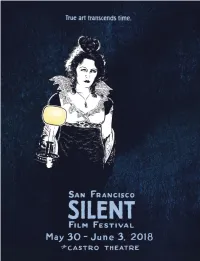

elcome to the San Francisco Silent Film Festival for five days and nights of live cinema! This is SFSFFʼs twenty-third year of sharing revered silent-era Wmasterpieces and newly revived discoveries as they were meant to be experienced—with live musical accompaniment. We’ve even added a day, so there’s more to enjoy of the silent-era’s treasures, including features from nine countries and inventive experiments from cinema’s early days and the height of the avant-garde. A nonprofit organization, SFSFF is committed to educating the public about silent-era cinema as a valuable historical and cultural record as well as an art form with enduring relevance. In a remarkably short time after the birth of moving pictures, filmmakers developed all the techniques that make cinema the powerful medium it is today— everything except for the ability to marry sound to the film print. Yet these films can be breathtakingly modern. They have influenced every subsequent generation of filmmakers and they continue to astonish and delight audiences a century after they were made. SFSFF also carries on silent cinemaʼs live music tradition, screening these films with accompaniment by the worldʼs foremost practitioners of putting live sound to the picture. Showcasing silent-era titles, often in restored or preserved prints, SFSFF has long supported film preservation through the Silent Film Festival Preservation Fund. In addition, over time, we have expanded our participation in major film restoration projects, premiering four features and some newly discovered documentary footage at this event alone. This year coincides with a milestone birthday of film scholar extraordinaire Kevin Brownlow, whom we celebrate with an onstage appearance on June 2.