Preservings $20 Issue No. 37, 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Green Spaces Brochure

Black Environment Network Ethnic Communities and Green Spaces Guidance for green space managers Green Space Location Type of space Theme Focus Use Improve Create 1 Abbeyfield Park Sheffield Urban park Multi-cultural festival in the park Park dept promoting use by ethnic communities / 2 Abney Park Cemetery London Local Nature Reserve Ecology, architecture and recreation Biodiversity awareness raising in mixed use space / 3 Al Hilal Manchester Community centre garden Improving the built environment Cultural and religious identity embodied in design / 4 Calthorpe Project London Multi-use green space Multi-functional inner city project Good design brings harmony among diverse users / 5 Cashel Forest Sterling Woodland (mixed) Commemorative forest of near-native ecology Refugee volunteers plant /tend commemorative trees / 6 Chelsea Physic Garden S. London Botanic garden Medicinal plants from around the world Pleasure visit/study facility with cultural links / 7 Chinese Hillside RBGE Edinburgh Botanic garden Simulated Chinese ecological landscape Living collection/ecological experiment / 8 Chumleigh Gardens S. London Multicultural gardens Park gardens recognising local ethnic presence Public park created garden reflecting different cultures / 9 Clovelly Centre Southampton Community centre garden Outdoor recreation space for older people Culturally sensitive garden design / 10 Concrete to Coriander Birmingham Community garden Expansion of park activities for food growing Safe access to land for Asian women / 11 Confused Spaces Birmingham Incidental -

Eco-Collaboration Between Higher Education and Ecovillages A

Partnerships for Sustainability: Eco-Collaboration between Higher Education and Ecovillages A PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Kiernan Jeanette Gladman IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF LIBERAL STUDIES February 2014 ©Kiernan Jeanette Gladman 2014 For John May the soles of our shoes wear down together. i Paradise (John Prine) When I was a child, my family would travel Down to western Kentucky where my parents were born And there's a backwards old town that's often remembered So many times that my memories are worn Chorus: And Daddy, won't you take me back to Muhlenberg County Down by the Green River where Paradise lay Well, I'm sorry, my son, but you're too late in asking Mister Peabody's coal train has hauled it away Well sometimes we'd travel right down the Green River To the abandoned old prison down by Adrie Hill Where the air smelled like snakes and we'd shoot with our pistols But empty pop bottles was all we would kill Chorus And the coal company came with the world's largest shovel And they tortured the timber and stripped all the land Well, they dug for their coal till the land was forsaken Then they wrote it all down as the progress of man Chorus When I die let my ashes float down the Green River Let my soul roll on up to the Rochester dam I'll be halfway to Heaven with Paradise waitin' Just five miles away from wherever I am Chorus ii CONTENTS ILLUSTRATIONS ............................................................................................................... -

Roots and Relationships of Greening Buildings

Eco-Architecture II 57 Roots and relationships of greening buildings S. Fruehwirth Institute of Architecture and Landscape, Technical University Graz, Austria Abstract In ancient Greece, the Hanging Gardens have their origin in the cult of Adonis. To honour Adonis, corn and spices were planted on the roof of the houses – and the Cult Garden emerged. By 2,600 BC it was reported that grapevines were used for arbours. Such functional uses were also found in Roman gardens: pergolas with rambling roses and arbour trails rambling with grapevines already existed. As protection against climatic influences, the grass roofs in Scandinavia and also in the hot southern regions were used to equalise temperature and create a pleasant indoor environment. Nowadays, similar temperature regulation is used in Austria and Hungary for subterranean wine cellars. Further subterranean buildings are military bunkers. They were built underneath artificial earth banks, and for a better camouflage, the roof was cropped. In his “five points of a new architecture”, Le Corbusier explained the necessity of roof greenings. This green roof was one of the first claims for a private green space generated with the atmosphere of nature. Looking at the individual origins of the history of covered buildings more closely, we can compare the different but sometimes similar use of plants to greening buildings in connection with contemporary architecture. Keywords: historical development of greening buildings, vertical garden, green facades, green roof. 1 Introduction The historic development of greening buildings has various origins. In this paper, the meaning of the creation of green roofs in ancient times and the first mention of tendrillar plants that are interwoven with a built horizontal and vertical environment will be analysed and recovered in contemporary architectural tendencies. -

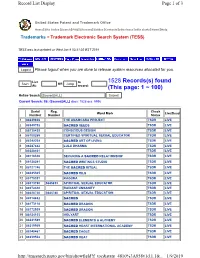

1528 Records(S) Found (This Page: 1 ~ 100)

Record List Display Page 1 of 3 United States Patent and Trademark Office Home |Site Index |Search |FAQ |Glossary |Guides |Contacts |eBusiness |eBiz alerts |News |Help Trademarks > Trademark Electronic Search System (TESS) TESS was last updated on Wed Jan 9 03:31:02 EST 2019 Logout Please logout when you are done to release system resources allocated for you. List to 1528 Records(s) found Start OR Jump At: record: (This page: 1 ~ 100) Refine Search (Sacred)[ALL] Submit Current Search: S6: (Sacred)[ALL] docs: 1528 occ: 5996 Serial Reg. Check Word Mark Live/Dead Number Number Status 1 88249836 THE ANAMCARA PROJECT TSDR LIVE 2 88249752 SACRED SEEDS TSDR LIVE 3 88130435 CONSCIOUS DESIGN TSDR LIVE 4 88100269 CERTIFIED SPIRITUAL SEXUAL EDUCATOR TSDR LIVE 5 88249209 SACRED ART OF LIVING TSDR LIVE 6 88247442 LULU DHARMA TSDR LIVE 7 88228461 TSDR LIVE 8 88116346 SECURING A SACRED RELATIONSHIP TSDR LIVE 9 88128241 SACRED WRITINGS STUDIO TSDR LIVE 10 88127748 THE SACRED RITUAL TSDR LIVE 11 88245305 SACRED OILS TSDR LIVE 12 88170351 KAGURA TSDR LIVE 13 88073190 5645833 SPIRITUAL SEXUAL EDUCATOR TSDR LIVE 14 88072440 RADIANT UNSANITY TSDR LIVE 15 88026720 5645780 SPIRITUAL SEXUAL EDUCATION TSDR LIVE 16 88014882 SACRED TSDR LIVE 17 88173118 SACRED DRAGON TSDR LIVE 18 88172939 SACRED DRAGON TSDR LIVE 19 88124103 HOLYART TSDR LIVE 20 88241589 SACRED ELEMENTS & ALCHEMY TSDR LIVE 21 88219959 SACRED HEART INTERNATIONAL ACADEMY TSDR LIVE 22 88240467 SACRED EAGLE TSDR LIVE 23 88239532 SACRED HEAT TSDR LIVE http://tmsearch.uspto.gov/bin/showfield?f=toc&state=4810%3A858v1d.1.1&.. -

The Expression of Sacred Space in Temple Mythology

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Unisa Institutional Repository EXPRESSONS OF SACRED SPACE: TEMPLE ARCHITECTURE IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST by Martin J Palmer submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Literature and Philosophy in the subject Ancient Near Eastern Studies at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA Promoter: Prof. P S Vermaak February 2012 ii ABSTRACT The objective of this thesis is to identify, isolate, and expound the concepts of sacred space and its ancillary doctrines and to show how they were expressed in ancient temple architecture and ritual. The fundamental concept of sacred space defined the nature of the holiness that pervaded the temple. The idea of sacred space included the ancient view of the temple as a mountain. Other subsets of the basic notion of sacred space include the role of the creation story in temple ritual, its status as an image of a heavenly temple and its location on the axis mundi, the temple as the site of the hieros gamos, the substantial role of the temple regarding kingship and coronation rites, the temple as a symbol of the Tree of Life, and the role played by water as a symbol of physical and spiritual blessings streaming forth from the temple. Temple ritual, architecture, and construction techniques expressed these concepts in various ways. These expressions, identified in the literary and archaeological records, were surprisingly consistent throughout the ancient Near East across large expanses of space and time. Under the general heading of Techniques of Construction and Decoration, this thesis examines the concept of the primordial mound and its application in temple architecture, the practice of foundation deposits, the purposes and functions of enclosure walls, principles of orientation, alignment, and measurement, and interior decorations. -

A Garden of Story and Mystery

AVALON A Garden of Story and netted wall and canopy Mystery up lawn up up pavilion water garden view from herb garden to pavilion and water garden herb garden viewing pond ramp The wall inspires an experience of boundary as well as of guidance; it both separates us from the outside and provides a reference to the change in topography. At the same time it encloses the space of the garden and guides one throughout the space. The Garden is a place of story and mystery; a juxtaposition of different elements to provide internal and external experience at multiple scales. At the scale of the landscape there is the ramp which provides a view across the estate and an intimate experience of the wall through touch, while the pond is the opposite, prompting one to look down into the water and into the space below the wall. At the scale of the garden, there is a dialogue between the heaviness of the wall to support plant growth and the ephemeral net which changes from wall to canopy and allows one to see the plants as a fi lter instead of as an object. At the human scale, the pavilion provides shelter and venue while the suspended water garden presents plants contained within glass vessels at varying heights for viewing by children and adults alike. The goal of the garden is to create a dynamic experience for both the gardener and the public. view from herb garden to viewing platform WRITTEN HISTORY, PERSONAL RECOLLECTION AND THE COMMUNAL SPACE OF THE GARDEN: THE HADSPEN PARABOLA A garden is a place where the natural becomes sculpted, set aside and put on display. -

OPTIONAL GROUP ACTIVITIES NYU Radiology in Santa Barbara Four Seasons, Santa Barbara October 19-23, 2009

OPTIONAL GROUP ACTIVITIES NYU Radiology in Santa Barbara Four Seasons, Santa Barbara October 19-23, 2009 The activities below have been arranged by TPI on an exclusive basis for NYU attendees so as not to conflict with the meeting agenda. TPI reserves the right to cancel or re-price any tours that do not meet the minimum requirements. Some activities require a commitment a month prior. Request after this date cannot be guaranteed. MONDAY, OCTOBER 19, 2009 ►Enchanted Santa Barbara 1:30pm-5:00pm $81 per adult $78 per child (5-18 years) Santa Barbara is one of the most beautiful small cities in the world. Guests invariably feel transported to a magical time and place in this city filled with unique architecture and relaxed vibes. Begin this unique tour by visiting Old Mission Santa Barbara, which is known as the Queen of the California Missions. The Mission’s sanctuary and chapel are still in use today, as is the Sacred Garden, which used to be closed to female visitors, with the exception of royalty or political wives, until 1959! After touring the Mission, head towards downtown Santa Barbara. The best way to discover the city is by following the steps of the famed “Red Tile” walking tour, which is a pleasant walk through just 12 short blocks in downtown Santa Barbara. Along the way, discover many of the city's oldest and most fascinating landmarks such as the Santa Barbara County Courthouse. This castle-like Spanish-Mediterranean stucco building lies in the center of Santa Barbara as a gleaming, glorious piece of architecture. -

Western Botanical Gardens: History and Evolution

5 Western Botanical Gardens: History and Evolution Donald A. Rakow Section of Horticulture School of Integrative Plant Science Cornell College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Ithaca, NY USA Sharon A. Lee Sharon Lee and Associates Swarthmore, PA USA ABSTRACT Dedicated to promoting an understanding of plants and their importance, the modern Western botanical garden addresses this mission through the establish- ment of educational programs, display and interpretation of collections, and research initiatives. The basic design and roles of the contemporary institution, however, can be traced to ancient Egypt, Persia, Greece, and Rome, where important elements emerged that would evolve over the centuries: the garden as walled and protected sanctuary, the garden as an organized space, and plants as agents of healing. In the Middle Ages, those concepts expanded to become the hortus conclusus, the walled monastery gardens where medicinal plants were grown. With intellectual curiosity at its zenith in the Renaissance, plants became subjects to be studied and shared. In the 16th and 17th centuries, botanical gardens in western Europe were teaching laboratories for university students studying medicine, botany, and what is now termed pharmacology. The need to teach students how to distinguish between medicinally active plants and poisonous plants led the first professor of botany in Europe, Francesco Bonafede, to propose the creation of the Orto botanico in Padua. Its initial curator was among the first to take plant collecting trips throughout Europe. Not to be Horticultural Reviews, Volume 43, First Edition. Edited by Jules Janick. 2015 Wiley-Blackwell. Published 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 269 270 D. -

The High Ground

The High Ground Sacred natural sites, bio-cultural diversity and climate change in the Eastern Himalayas © WWF-BHUTAN © WWF-Canon / Steve Morgan The High Ground: Sacred natural sites, bio-cultural diversity and climate change in the Eastern Himalayas Edited by Liza Higgins-Zogib, Nigel Dudley, Tariq Aziz and Savita Malla Published in 2011 by WWF World Wide Fund for Nature ISBN: 978-2-940443-28-4 Cover photograph: Temple above Taksang, Bhutan, © BhanuwatJittivuthikorn No photographs from this publication may be reproduced on the World Wide Web without prior authorization. Disclaimer The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official positions of the organizations involved. The material and the geographical designations in this report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WWF concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. © WWF-US / Jon Miceler FOREWORD The Eastern Himalayas is one of the most beautiful and fascinating places on our planet. Its biodiversity and its cultural richness are to be celebrated, and cherished. Nature and culture are intimately linked in the Himalayas -- particularly through the deep reverence that the regions faiths hold for the natural world. WWF has embraced the Eastern Himalayan region as one where we are determined to make a lasting difference because we realize just how critical it is for the worlds natural © WWF-Canon / R. Stonehouse and cultural heritage and for the future well-being of people across the region. We have long understood the linkage between nature and culture in its broadest sense, but we are just beginning to come to terms with the strong interdependence between the environment and spiritual practices, so prominent in this particular region. -

State of Hawaii Department of the Attorney General

Organizations that have applied STATE OF HAWAII for and been granted an DEPARTMENT OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL exemption from registration pursuant to HRS Section 467B-11.5 Date of Exemption FEIN Name of Charity Address Ruling Reason for Confirmation of Exemption 99-0285135 AIDS Community Care Team 4224 Waialae Avenue #420, Honolulu, HI 96816 4/22/2009 Receives less than $25,000 in contributions annually 43-0356250 A.T. Still University 800 W. Jefferson St., Kirksville, MO 63051 6/26/2012 An educational institution 99-0107223 Academy of the Pacific 913 Alewa Drive, Honolulu, HI 96817 1/30/2013 An educational institution 99-0266482 Admiral Arthur W. Radford High 4361 Salt Lake Boulevard, Honolulu, HI 96818 4/30/2013 A State Agency 99-0266482 Admiral Chester W. Nimitz Elementary 520 Main Street, Honolulu, HI 96818 4/30/2013 A State Agency 45-4804012 Advantage Sports Academy, Inc. 128 Ainoni St., Kailua, HI 96734 2/26/2014 Receives less than $25,000 in contributions annually 65-0133113 Adventures in Missions, Inc. 6000 Wellspring Trail, Gainesville, GA 30506 11/22/2013 A duly religious corporation, institution or society 94-3282558 African American Diversity Cultural Center Hawaii 1311 Kapiolani Blvd., #203, Honolulu, HI 96814 2/26/2014 Receives less than $25,000 in contributions annually 99-0234399 Agon Mission of Hawaii 1720 Ala Moana Blvd. B-1-C, Honolulu, HI 96815 6/3/2009 Receives less than $25,000 in contributions annually 23-7253559 Ahui Koa Anuenue 1337 Lower Campus Road, Honolulu, HI 96822 7/6/2012 Receives less than $25,000 in contributions -

The Sacred Garden of Lumbini: Perceptions of Buddha's Birthplace

The Sacred Garden of Lumbini Perceptions of Buddha’s birthplace | 1 The Sacred Garden of Lumbini Perceptions of Buddha’s birthplace Published in 2013 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France © UNESCO 2013 Available in Open Access. Use, re-distribution, translations and derivative works of this publication are allowed on the basis that the original source (i.e. The Sacred Garden of Lumbini. Perceptions of Buddha’s Birthplace /© UNESCO) is properly quoted and the new creation is distributed under identical terms as the original. The present license Contents applies exclusively to the text content of the publication. For use of any other material (i.e. texts, images, illustrations, charts) not clearly identified as belonging to UNESCO Foreword 1 or being in the public domain, prior permission shall be requested from UNESCO: [email protected] or UNESCO Publications, 7, place de Fontenoy, About the publication 3 75352 Paris 07 SP France. Introduction 5 ISBN 978-92-3-001208-3 kl/ro 13 The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO Perception One The garden of the gods Lumbini in early concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or Buddhist literature 19 concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Interpretation of Buddhist literature . 20 The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. -

Jan Lindstrom

Volume 25 Issue 4 April 2019 THE PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE It is FINALLY Spring in Hudson!!! Very exciting to know we have (basically) made it through another Northeast Ohio winter. I’m encouraged by the bulbs that are starting to grow in my yard. Last fall I planted 500 mini daffodils in a number of varieties and I no longer remember where I planted them. I’m looking forward to what I know will be a pleasant surprise! We will now really be kicking in to high gear on planning for the upcoming 72nd Home & Garden Tour. What a rich tradition we bring to Hudson. Not only residents but others from the greater Akron/Cleveland and beyond area have an opportunity to experience a taste of the community we all enjoy on a daily basis. Please be sure to note the article on the Garden Shop Resale donations that are needed. Judy Mikita is ready to accept your donations of items to sell - anything gardening - pots, planters, tools! Something you no longer need will become someone else’s treasure. So as you start working outside and find something that could use a new home, reach out to Judy. This month’s newsletter is out a bit early due to upcoming deadlines for very exciting field trip opportunities. Please see all the details in this newsletter and make your reservations ASAP. Jan Lindstrom COOKIES AND VOLUNTEERS ITEMS NEEDED NEEDED FOR HUDSON GARDEN TOUR’S FOR GARDEN TEA ROOM Camille Kuri & Sue Swain SHOP We are excited to be hosting the Hudson Home & Garden Tour’s Tea Room again this summer! We will be Do you have gently used thrilled to have you volunteer to help us in the Tea pots and planters that you Room or to bake cookies.