A Garden of Story and Mystery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Green Spaces Brochure

Black Environment Network Ethnic Communities and Green Spaces Guidance for green space managers Green Space Location Type of space Theme Focus Use Improve Create 1 Abbeyfield Park Sheffield Urban park Multi-cultural festival in the park Park dept promoting use by ethnic communities / 2 Abney Park Cemetery London Local Nature Reserve Ecology, architecture and recreation Biodiversity awareness raising in mixed use space / 3 Al Hilal Manchester Community centre garden Improving the built environment Cultural and religious identity embodied in design / 4 Calthorpe Project London Multi-use green space Multi-functional inner city project Good design brings harmony among diverse users / 5 Cashel Forest Sterling Woodland (mixed) Commemorative forest of near-native ecology Refugee volunteers plant /tend commemorative trees / 6 Chelsea Physic Garden S. London Botanic garden Medicinal plants from around the world Pleasure visit/study facility with cultural links / 7 Chinese Hillside RBGE Edinburgh Botanic garden Simulated Chinese ecological landscape Living collection/ecological experiment / 8 Chumleigh Gardens S. London Multicultural gardens Park gardens recognising local ethnic presence Public park created garden reflecting different cultures / 9 Clovelly Centre Southampton Community centre garden Outdoor recreation space for older people Culturally sensitive garden design / 10 Concrete to Coriander Birmingham Community garden Expansion of park activities for food growing Safe access to land for Asian women / 11 Confused Spaces Birmingham Incidental -

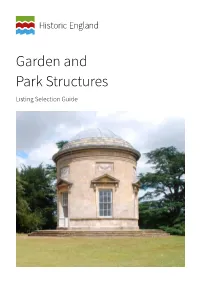

Garden and Park Structures Listing Selection Guide Summary

Garden and Park Structures Listing Selection Guide Summary Historic England’s twenty listing selection guides help to define which historic buildings are likely to meet the relevant tests for national designation and be included on the National Heritage List for England. Listing has been in place since 1947 and operates under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. If a building is felt to meet the necessary standards, it is added to the List. This decision is taken by the Government’s Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). These selection guides were originally produced by English Heritage in 2011: slightly revised versions are now being published by its successor body, Historic England. The DCMS‘ Principles of Selection for Listing Buildings set out the over-arching criteria of special architectural or historic interest required for listing and the guides provide more detail of relevant considerations for determining such interest for particular building types. See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/principles-of- selection-for-listing-buildings. Each guide falls into two halves. The first defines the types of structures included in it, before going on to give a brisk overview of their characteristics and how these developed through time, with notice of the main architects and representative examples of buildings. The second half of the guide sets out the particular tests in terms of its architectural or historic interest a building has to meet if it is to be listed. A select bibliography gives suggestions for further reading. This guide looks at buildings and other structures found in gardens, parks and indeed designed landscapes of all types from the Middle Ages to the twentieth century. -

Ideas and Tradition Behind Chinese and Western Landscape Design

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Landscape Planning, Horticulture and Agricultural Science Department of Landscape Architecture Ideas and Tradition behind Chinese and Western Landscape Design - similarities and differences Junying Pang Degree project in landscape planning, 30 hp Masterprogramme Urban Landscape Dynamics Independent project at the LTJ Faculty, SLU Alnarp 2012 1 Idéer och tradition bakom kinesisk och västerländsk landskapsdesign Junying Pang Supervisor: Kenneth Olwig, SLU, Department of Landscape Architecture , , Assistant Supervisor: Anna Jakobsson, SLU, Department of Landscape Architecture , , Examiner: Eva Gustavsson, SLU, Department of Landscape Architecture , , Credits: 30 hp Level: A2E Course title: Degree Project in the Masterprogramme Urban Landscape Dynamics Course code: EX0377 Programme/education: Masterprogramme Urban Landscape Dynamics Subject: Landscape planning Place of publication: Alnarp Year of publication: January 2012 Picture cover: http://photo.zhulong.com/proj/detail4350.htm Series name: Independent project at the LTJ Faculty, SLU Online publication: http://stud.epsilon.slu.se Key Words: Ideas, Tradition, Chinese landscape Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Landscape Planning, Horticulture and Agricultural Science Department of Landscape Architecture 2 Forward This degree project was written by the student from the Urban Landscape Dynamics (ULD) Programme at Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU). This programme is a two years master programme, and it relates to planning and designing of the urban landscape. The level and depth of this degree project is Master E, and the credit is 30 Ects. Supervisor of this degree project has been Kenneth Olwig, professor at the Department of Landscape architecture; assistant supervisor has been Anna Jakobsson, teacher and research assistant at the Department of Landscape architecture; master’s thesis coordinator has been Eva Gustavsson, senior lecturer at the Department of Landscape architecture. -

Eco-Collaboration Between Higher Education and Ecovillages A

Partnerships for Sustainability: Eco-Collaboration between Higher Education and Ecovillages A PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Kiernan Jeanette Gladman IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF LIBERAL STUDIES February 2014 ©Kiernan Jeanette Gladman 2014 For John May the soles of our shoes wear down together. i Paradise (John Prine) When I was a child, my family would travel Down to western Kentucky where my parents were born And there's a backwards old town that's often remembered So many times that my memories are worn Chorus: And Daddy, won't you take me back to Muhlenberg County Down by the Green River where Paradise lay Well, I'm sorry, my son, but you're too late in asking Mister Peabody's coal train has hauled it away Well sometimes we'd travel right down the Green River To the abandoned old prison down by Adrie Hill Where the air smelled like snakes and we'd shoot with our pistols But empty pop bottles was all we would kill Chorus And the coal company came with the world's largest shovel And they tortured the timber and stripped all the land Well, they dug for their coal till the land was forsaken Then they wrote it all down as the progress of man Chorus When I die let my ashes float down the Green River Let my soul roll on up to the Rochester dam I'll be halfway to Heaven with Paradise waitin' Just five miles away from wherever I am Chorus ii CONTENTS ILLUSTRATIONS ............................................................................................................... -

A New Center Stage

engage a sustainable vision for the mall that captures the create an enhanced landscape that enriches the experience of provide flexible performance settings and a nurture culture and cultivation to support rich sylvan grove syLvaN cONNectIONs surprise and magic of a sylvan setting reframe aN IcONIc settING the washington monument grounds a hIGh perfOrmaNce LaNdscape compelling sustainable vision a Layered LaNdscape ecology on the national mall a New perfOrmaNce hOrIzON a new center stage The National Mall is our nation’s center stage and the site of some of the most important acts of communication and communion in our country. At the heart of the Mall and visible for miles, the Washington Monument is the literal and philosophical compass for our nation – a timeless symbol of the spirit upon which our nation was founded. Extending from this central landmark, the 1 TREET S rejuvenated Sylvan Theater and Sylvan TH 15 Grove embody the surprise and magic of the Shakespearean forest that inspired the name of the original theater nearly a century ago. 2 3 2 19 4 23 7 8 6 17 9 20 5 15 13 WASHINGTON MONUMENT GROUNDS WASHINGTON, D.C. CULTURAL LANDSCAPE REPORT 10 * * 12 INDEPENDENCE AVENUE 21 14 * D 2008) M . ( 2003 F H 11 S ARCH REV ECEMBER IGURES ISTORY ITE 16 Figure 2-31. Plan for the improvement of the west side of monument park, 1902. park, monument of side west the of improvement the for Plan 2-31. Figure S 15 OURCE : NPS-NCR : C a framed approach An arrival view from the nearby Smithsonian museums and metro frames active programs on the renewed Monument Grounds. -

Arbor, Trellis, Or Pergola—What's in Your Garden?

ENH1171 Arbor, Trellis, or Pergola—What’s in Your Garden? A Mini-Dictionary of Garden Structures and Plant Forms1 Gail Hansen2 ANY OF THE garden features and planting Victorian era (mid-nineteenth century) included herbaceous forms in use today come from the long and rich borders, carpet bedding, greenswards, and strombrellas. M horticultural histories of countries around the world. The use of garden structures and intentional plant Although many early garden structures and plant forms forms originated in the gardens of ancient Mesopotamia, have changed little over time and are still popular today, Egypt, Persia, and China (ca. 2000–500 BC). The earliest they are not always easy to identify. Structures have been gardens were a utilitarian mix of flowering and fruiting misidentified and names have varied over time and by trees and shrubs with some herbaceous medicinal plants. region. Read below to find out more about what might be in Arbors and pergolas were used for vining plants, and your garden. Persian gardens often included reflecting pools and water features. Ancient Romans (ca. 100) were perhaps the first to Garden Structures for People plant primarily for ornamentation, with courtyard gardens that included trompe l’oeil, topiary, and small reflecting Arbor: A recessed or somewhat enclosed area shaded by pools. trees or shrubs that serves as a resting place in a wooded area. In a more formal garden, an arbor is a small structure The early medieval gardens of twelfth-century Europe with vines trained over latticework on a frame, providing returned to a more utilitarian role, with culinary and a shady place. -

Roots and Relationships of Greening Buildings

Eco-Architecture II 57 Roots and relationships of greening buildings S. Fruehwirth Institute of Architecture and Landscape, Technical University Graz, Austria Abstract In ancient Greece, the Hanging Gardens have their origin in the cult of Adonis. To honour Adonis, corn and spices were planted on the roof of the houses – and the Cult Garden emerged. By 2,600 BC it was reported that grapevines were used for arbours. Such functional uses were also found in Roman gardens: pergolas with rambling roses and arbour trails rambling with grapevines already existed. As protection against climatic influences, the grass roofs in Scandinavia and also in the hot southern regions were used to equalise temperature and create a pleasant indoor environment. Nowadays, similar temperature regulation is used in Austria and Hungary for subterranean wine cellars. Further subterranean buildings are military bunkers. They were built underneath artificial earth banks, and for a better camouflage, the roof was cropped. In his “five points of a new architecture”, Le Corbusier explained the necessity of roof greenings. This green roof was one of the first claims for a private green space generated with the atmosphere of nature. Looking at the individual origins of the history of covered buildings more closely, we can compare the different but sometimes similar use of plants to greening buildings in connection with contemporary architecture. Keywords: historical development of greening buildings, vertical garden, green facades, green roof. 1 Introduction The historic development of greening buildings has various origins. In this paper, the meaning of the creation of green roofs in ancient times and the first mention of tendrillar plants that are interwoven with a built horizontal and vertical environment will be analysed and recovered in contemporary architectural tendencies. -

Ashe RFP Draft 033014.Docx

Request for Proposal (RFP) Edible Schoolyard NOLA Arthur Ashe Charter School Oak Park Garden Pavilion and Accessory Landscape Features Proposals must be received by: Noon on Wednesday, May 28, 2014 Edible Schoolyard NOLA 2319 Valence St New Orleans, LA 70115 (504) 376-7693 for more information, visit: www.esynola.org Page | 1 ESYNOLA, Arthur Ashe Charter School Oak Park Garden Pavilion and Accessory Landscape Features Table of Contents I. Introduction: 3 A. Purpose for Request for Proposal 3 B. Background about the Edible Schoolyard NOLA 3 II. Scope of Work and Budget 4 A. Scope of Services 4 B. Budget 7 C. Design and Development Schedule 8 D. Contract Period 9 E. Timeline: 9 III. Submission Requirements 9 A. Review for Compliance with Mandatory RFP Requirements 9 B. Questions on the Request for Proposal 10 C. Mandatory Submission Requirements 10 D. Submission Instructions 10 E. Review Process 11 F. Notification of Decision: 11 G. Protest Process 11 IV. Confidentiality of Responses 12 V. Miscellaneous Information: 12 Attachment A – Cover Page 13 Attachment B – Statement of Qualifications 14 Attachment C – Project Data Sheets 15 Attachment D – Bid Sheets 21 Attachment E – Non-Collusion Affidavit 22 Exhibit 1 – Evaluation Criteria…………………………………………………………………………23 Exhibit 2 – Map of Campus…….…...…………………………………………………………………24 Exhibit 3 – Preliminary Site Plan…...…………………………………………………………………25 Exhibit 4 – Image Scrapbook.……...………………………………………………………………….26 Page | 2 Request for Proposal FirstLine Schools Edible Schoolyard at Arthur Ashe Charter School Oak Park Garden Pavilion and Accessory Landscape Features I. Introduction: Edible Schoolyard New Orleans (ESYNOLA), a signature program of FirstLine Schools, requests proposals for design and construction services to create a set of structures that will complete the infrastructure for our Edible Schoolyard at Arthur Ashe Charter School. -

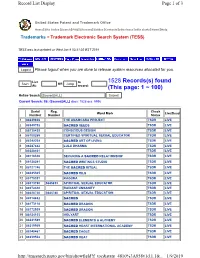

1528 Records(S) Found (This Page: 1 ~ 100)

Record List Display Page 1 of 3 United States Patent and Trademark Office Home |Site Index |Search |FAQ |Glossary |Guides |Contacts |eBusiness |eBiz alerts |News |Help Trademarks > Trademark Electronic Search System (TESS) TESS was last updated on Wed Jan 9 03:31:02 EST 2019 Logout Please logout when you are done to release system resources allocated for you. List to 1528 Records(s) found Start OR Jump At: record: (This page: 1 ~ 100) Refine Search (Sacred)[ALL] Submit Current Search: S6: (Sacred)[ALL] docs: 1528 occ: 5996 Serial Reg. Check Word Mark Live/Dead Number Number Status 1 88249836 THE ANAMCARA PROJECT TSDR LIVE 2 88249752 SACRED SEEDS TSDR LIVE 3 88130435 CONSCIOUS DESIGN TSDR LIVE 4 88100269 CERTIFIED SPIRITUAL SEXUAL EDUCATOR TSDR LIVE 5 88249209 SACRED ART OF LIVING TSDR LIVE 6 88247442 LULU DHARMA TSDR LIVE 7 88228461 TSDR LIVE 8 88116346 SECURING A SACRED RELATIONSHIP TSDR LIVE 9 88128241 SACRED WRITINGS STUDIO TSDR LIVE 10 88127748 THE SACRED RITUAL TSDR LIVE 11 88245305 SACRED OILS TSDR LIVE 12 88170351 KAGURA TSDR LIVE 13 88073190 5645833 SPIRITUAL SEXUAL EDUCATOR TSDR LIVE 14 88072440 RADIANT UNSANITY TSDR LIVE 15 88026720 5645780 SPIRITUAL SEXUAL EDUCATION TSDR LIVE 16 88014882 SACRED TSDR LIVE 17 88173118 SACRED DRAGON TSDR LIVE 18 88172939 SACRED DRAGON TSDR LIVE 19 88124103 HOLYART TSDR LIVE 20 88241589 SACRED ELEMENTS & ALCHEMY TSDR LIVE 21 88219959 SACRED HEART INTERNATIONAL ACADEMY TSDR LIVE 22 88240467 SACRED EAGLE TSDR LIVE 23 88239532 SACRED HEAT TSDR LIVE http://tmsearch.uspto.gov/bin/showfield?f=toc&state=4810%3A858v1d.1.1&.. -

TURQUERIE in the WEST-EUROPEAN LANDSCAPE GARDENS in the 18Th and in the EARLY 19Th CENTURIES 18

171-180 EEVA RUOFF:TUBAKED8/2010 10/20/11 1:17 AM Page TÜBA-KED 9/2011 TURQUERIE IN THE WEST-EUROPEAN LANDSCAPE GARDENS IN THE 18th AND IN THE EARLY 19th CENTURIES 18. YÜZYIL VE ERKEN 19. YÜZYIL BATI-AVRUPA BAHÇELERİNDE TURQUERIE Eeva RUOFF Keywords - Anahtar Sözcükler: 18th century, 19th century, Europe, garden, Turquerie 18. yüzyıl, 19. yüzyıl, Avrupa, bahçe, Turquerie ABSTRACT "Turkish" tents and other Turkish inspired buildings were time and again set up at visually important points in the West-European landscape gardens in the 18th century and in the early 19th century. They reflected the gen eral interest for Turkey felt among the more enlightened Europeans that manifested itself also in many other ways, e.g. Turkish music and Turkish masquerades. Tents were probably chosen as references for Turkey, because the tents of the Turkish army were renowned for their high quality. Yet, the tents made of fabric have -for obvious reasons - not survived as well as other garden buildings of the era. Therefore little research has so far been done on their role in the landscape gardens. In some gardens there were, however, also other "Turkish" buildings, for instance kiosks, "mosques" and pavilions that survived for a longer time, still exist or have occasionally been reconstructed. There can also have been further, ideological reasons for the "Turkish" buildings. They may sometimes have been erected to remind the garden visitors of the lofty principle that all people are brothers and equals - ideas first formulated by the freemasons and Rosicrucians. The members of these societies also believed that much of the ancient wisdom, especially mathematics, had been developed by the peoples living in the East Mediterranean area. -

THE BARCELONA PAVILION AS LANDSCAPE GARDEN: MODERNITY and the PICTURESQUE Author(S): Caroline Constant Source: AA Files, No

THE BARCELONA PAVILION AS LANDSCAPE GARDEN: MODERNITY AND THE PICTURESQUE Author(s): Caroline Constant Source: AA Files, No. 20 (Autumn 1990), pp. 46-54 Published by: Architectural Association School of Architecture Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/29543706 . Accessed: 26/09/2014 12:50 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Architectural Association School of Architecture is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to AA Files. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Fri, 26 Sep 2014 12:50:54 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE BARCELONA PAVILION AS LANDSCAPE GARDEN MODERNITY AND THE PICTURESQUE Caroline Constant 'A work of architecture must not stand as a finished and self afforded Mies the freedom to pursue the expressive possibilities of sufficient object. True and pure imagination, having once entered the discipline. During the 1920s he had begun to abandon the formal the stream of the idea that it expresses, has to expand forever logic of the classical idiom, with itsmimesis of man and nature, in beyond thiswork, and itmust venture out, leading ultimately to the favour of specifically architectural means. -

Fall/Winter 2021-2022 Activity Guide

Our Mission To provide high quality parks, facilities, and recreation services that enhance residents’ lives through responsible and effective management of resources. Report an Issue If you see suspicious activities, vandalism or problems within a St. Louis County park, please call the Park Watch Hotline at Dear St. Louis County residents, (314) 615-ISEE (4733) or (800) 735-2966 TTY (Relay Missouri). You may remain anonymous. St. Louis County is a great place to live, work and raise a family. To contact a Park Ranger call (314) 615-8911. To report a crime in progress or a medical emergency, call 911. One of the highlights of the County is our dedicated green spaces. Our St. Louis County Parks and Recreation Accessibility Department staff work hard year-round to keep our parks St. Louis County Parks Department welcomes people of all beautiful. As the days grow cooler, our parks burst with the abilities to participate in our programs and services. If you or someone you know has a disability and would like to participate colors of Fall and outdoor activities. in one of our programs or activities, please let us know how we can best meet your needs. Alternative formats (braille, large Our dedicated park staff are diligently preparing a wide print etc.) of this Parks Activity Guide can be provided upon variety of programming to enhance your experience during request. Please contact us at (314) 615-4386 or Relay MO at the Fall and Winter. 711 or (800) 735-2966 as soon as possible but no later than 48 hours (two business days) before a scheduled event.