Land Sovereignty Publication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Green Spaces Brochure

Black Environment Network Ethnic Communities and Green Spaces Guidance for green space managers Green Space Location Type of space Theme Focus Use Improve Create 1 Abbeyfield Park Sheffield Urban park Multi-cultural festival in the park Park dept promoting use by ethnic communities / 2 Abney Park Cemetery London Local Nature Reserve Ecology, architecture and recreation Biodiversity awareness raising in mixed use space / 3 Al Hilal Manchester Community centre garden Improving the built environment Cultural and religious identity embodied in design / 4 Calthorpe Project London Multi-use green space Multi-functional inner city project Good design brings harmony among diverse users / 5 Cashel Forest Sterling Woodland (mixed) Commemorative forest of near-native ecology Refugee volunteers plant /tend commemorative trees / 6 Chelsea Physic Garden S. London Botanic garden Medicinal plants from around the world Pleasure visit/study facility with cultural links / 7 Chinese Hillside RBGE Edinburgh Botanic garden Simulated Chinese ecological landscape Living collection/ecological experiment / 8 Chumleigh Gardens S. London Multicultural gardens Park gardens recognising local ethnic presence Public park created garden reflecting different cultures / 9 Clovelly Centre Southampton Community centre garden Outdoor recreation space for older people Culturally sensitive garden design / 10 Concrete to Coriander Birmingham Community garden Expansion of park activities for food growing Safe access to land for Asian women / 11 Confused Spaces Birmingham Incidental -

Eco-Collaboration Between Higher Education and Ecovillages A

Partnerships for Sustainability: Eco-Collaboration between Higher Education and Ecovillages A PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Kiernan Jeanette Gladman IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF LIBERAL STUDIES February 2014 ©Kiernan Jeanette Gladman 2014 For John May the soles of our shoes wear down together. i Paradise (John Prine) When I was a child, my family would travel Down to western Kentucky where my parents were born And there's a backwards old town that's often remembered So many times that my memories are worn Chorus: And Daddy, won't you take me back to Muhlenberg County Down by the Green River where Paradise lay Well, I'm sorry, my son, but you're too late in asking Mister Peabody's coal train has hauled it away Well sometimes we'd travel right down the Green River To the abandoned old prison down by Adrie Hill Where the air smelled like snakes and we'd shoot with our pistols But empty pop bottles was all we would kill Chorus And the coal company came with the world's largest shovel And they tortured the timber and stripped all the land Well, they dug for their coal till the land was forsaken Then they wrote it all down as the progress of man Chorus When I die let my ashes float down the Green River Let my soul roll on up to the Rochester dam I'll be halfway to Heaven with Paradise waitin' Just five miles away from wherever I am Chorus ii CONTENTS ILLUSTRATIONS ............................................................................................................... -

Faith on the Avenue

FAITH ON THE AVENUE DDay200613OUS.indday200613OUS.indd i 110/29/20130/29/2013 99:47:25:47:25 PPMM DDay200613OUS.indday200613OUS.indd iiii 110/29/20130/29/2013 99:47:26:47:26 PPMM FAITH ON THE AVENUE Religion on a City Street Katie Day Photographs by Edd Conboy 1 DDay200613OUS.indday200613OUS.indd iiiiii 110/29/20130/29/2013 99:47:26:47:26 PPMM 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Th ailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 © Oxford University Press 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. -

Roots and Relationships of Greening Buildings

Eco-Architecture II 57 Roots and relationships of greening buildings S. Fruehwirth Institute of Architecture and Landscape, Technical University Graz, Austria Abstract In ancient Greece, the Hanging Gardens have their origin in the cult of Adonis. To honour Adonis, corn and spices were planted on the roof of the houses – and the Cult Garden emerged. By 2,600 BC it was reported that grapevines were used for arbours. Such functional uses were also found in Roman gardens: pergolas with rambling roses and arbour trails rambling with grapevines already existed. As protection against climatic influences, the grass roofs in Scandinavia and also in the hot southern regions were used to equalise temperature and create a pleasant indoor environment. Nowadays, similar temperature regulation is used in Austria and Hungary for subterranean wine cellars. Further subterranean buildings are military bunkers. They were built underneath artificial earth banks, and for a better camouflage, the roof was cropped. In his “five points of a new architecture”, Le Corbusier explained the necessity of roof greenings. This green roof was one of the first claims for a private green space generated with the atmosphere of nature. Looking at the individual origins of the history of covered buildings more closely, we can compare the different but sometimes similar use of plants to greening buildings in connection with contemporary architecture. Keywords: historical development of greening buildings, vertical garden, green facades, green roof. 1 Introduction The historic development of greening buildings has various origins. In this paper, the meaning of the creation of green roofs in ancient times and the first mention of tendrillar plants that are interwoven with a built horizontal and vertical environment will be analysed and recovered in contemporary architectural tendencies. -

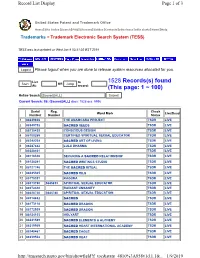

1528 Records(S) Found (This Page: 1 ~ 100)

Record List Display Page 1 of 3 United States Patent and Trademark Office Home |Site Index |Search |FAQ |Glossary |Guides |Contacts |eBusiness |eBiz alerts |News |Help Trademarks > Trademark Electronic Search System (TESS) TESS was last updated on Wed Jan 9 03:31:02 EST 2019 Logout Please logout when you are done to release system resources allocated for you. List to 1528 Records(s) found Start OR Jump At: record: (This page: 1 ~ 100) Refine Search (Sacred)[ALL] Submit Current Search: S6: (Sacred)[ALL] docs: 1528 occ: 5996 Serial Reg. Check Word Mark Live/Dead Number Number Status 1 88249836 THE ANAMCARA PROJECT TSDR LIVE 2 88249752 SACRED SEEDS TSDR LIVE 3 88130435 CONSCIOUS DESIGN TSDR LIVE 4 88100269 CERTIFIED SPIRITUAL SEXUAL EDUCATOR TSDR LIVE 5 88249209 SACRED ART OF LIVING TSDR LIVE 6 88247442 LULU DHARMA TSDR LIVE 7 88228461 TSDR LIVE 8 88116346 SECURING A SACRED RELATIONSHIP TSDR LIVE 9 88128241 SACRED WRITINGS STUDIO TSDR LIVE 10 88127748 THE SACRED RITUAL TSDR LIVE 11 88245305 SACRED OILS TSDR LIVE 12 88170351 KAGURA TSDR LIVE 13 88073190 5645833 SPIRITUAL SEXUAL EDUCATOR TSDR LIVE 14 88072440 RADIANT UNSANITY TSDR LIVE 15 88026720 5645780 SPIRITUAL SEXUAL EDUCATION TSDR LIVE 16 88014882 SACRED TSDR LIVE 17 88173118 SACRED DRAGON TSDR LIVE 18 88172939 SACRED DRAGON TSDR LIVE 19 88124103 HOLYART TSDR LIVE 20 88241589 SACRED ELEMENTS & ALCHEMY TSDR LIVE 21 88219959 SACRED HEART INTERNATIONAL ACADEMY TSDR LIVE 22 88240467 SACRED EAGLE TSDR LIVE 23 88239532 SACRED HEAT TSDR LIVE http://tmsearch.uspto.gov/bin/showfield?f=toc&state=4810%3A858v1d.1.1&.. -

Federal Register/Vol. 63, No. 129/Tuesday, July 7, 1998/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 63, No. 129 / Tuesday, July 7, 1998 / Notices 36709 necessary for the proper performance of title interest, of operating rights, or Faulkner County the functions of the agency, including overriding royalty or similar interest in Sailor, C.L., House, Wilson St., Bigelow, whether the information will have a lease to another party under the terms 98000880 practical utility; (b) the accuracy of the of the mineral leasing laws. Little River County agency's estimate of the burden of the Since the filing of the assignment or St. Barnabas Episcopal Church, Jct. of Tracy proposed collection, including the transfer for final Secretarial approval is validity of the methodology and Lawrence Ave. and Bell St., Foreman, required by law, the forms are used to 98000910 assumptions used; (c) ways to enhance help the assignor/transferor provide the Prairie County the quality, utility, and clarity of the basic information needed by the BLM to information to be collected; and (d) identify ownership of the interest being BarrettÐRogers Building, 100 N. Hazen Ave., ways to minimize the burden of the Hazen, 98000881 assigned/transferred and qualifications collection of information on those who of the transferee/assignee to take COLORADO are to respond, including through the interest. The information is necessary to use of appropriate automated, Jefferson County ensure that the assignee/transferee is electronic, mechanical, or other qualified, in accordance with the Churches Ranch, 17999 W. 60th Ave., technological collection techniques or Arvada, 98000883 statutory requirements, to obtain the other forms of information technology. CONNECTICUT The Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 (30 interest sought in an oil and gas or U.S.C. -

CONTACT: Arturo Varela (267) 765-0367, [email protected] Daniel Davis (267) 546-0758, [email protected] Tweet Us: @Visitphillypr

CONTACT: Arturo Varela (267) 765-0367, [email protected] Daniel Davis (267) 546-0758, [email protected] Tweet Us: @visitphillyPR Tweet It: A brochure from @visitphilly explores the region’s Underground Railroad: https://vstphl.ly/2UsF712 PHILADELPHIA’S UNDERGROUND RAILROAD SITES From Mother Bethel A.M.E. To The Johnson House PHILADELPHIA, January 31, 2019 – VISIT PHILADELPHIA® has published a detailed guide for visitors and residents interested in exploring the Philadelphia region’s many connections to the Underground Railroad. The six-panel brochure catalogs historical attractions (the Liberty Bell Center, Mother Bethel A.M.E., Belmont Mansion, Johnson House, Fair Hill burial ground), historical markers (London Coffee House, Free African Society and homes of Cyrus Bustill, Frances E.W. Harper, Robert Purvis, William Still, William Whipper) and city and regional libraries, archives and tours. Featured Sites: The brochure is available at the Independence Visitor Center, the African American Museum in Philadelphia, the Johnson House in historic Germantown and more. It is also available online at: visitphilly.com/underground-railroad-in-philadelphia. Here is a look at some of the public sites featured in the brochure and one new addition* that will be added upon the next publication: 1. Liberty Bell Center: Home to the famous Bell, a symbol adopted by abolitionist societies in the 1830s and later by freedom seekers around the world. 6th & Market Streets, nps.gov/inde 2. President’s House: Freedom and Slavery in the Making of a New Nation: Memorial site of the home where President George Washington lived and enslaved nine Africans, including Oney Judge, who escaped bondage. -

The Expression of Sacred Space in Temple Mythology

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Unisa Institutional Repository EXPRESSONS OF SACRED SPACE: TEMPLE ARCHITECTURE IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST by Martin J Palmer submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Literature and Philosophy in the subject Ancient Near Eastern Studies at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA Promoter: Prof. P S Vermaak February 2012 ii ABSTRACT The objective of this thesis is to identify, isolate, and expound the concepts of sacred space and its ancillary doctrines and to show how they were expressed in ancient temple architecture and ritual. The fundamental concept of sacred space defined the nature of the holiness that pervaded the temple. The idea of sacred space included the ancient view of the temple as a mountain. Other subsets of the basic notion of sacred space include the role of the creation story in temple ritual, its status as an image of a heavenly temple and its location on the axis mundi, the temple as the site of the hieros gamos, the substantial role of the temple regarding kingship and coronation rites, the temple as a symbol of the Tree of Life, and the role played by water as a symbol of physical and spiritual blessings streaming forth from the temple. Temple ritual, architecture, and construction techniques expressed these concepts in various ways. These expressions, identified in the literary and archaeological records, were surprisingly consistent throughout the ancient Near East across large expanses of space and time. Under the general heading of Techniques of Construction and Decoration, this thesis examines the concept of the primordial mound and its application in temple architecture, the practice of foundation deposits, the purposes and functions of enclosure walls, principles of orientation, alignment, and measurement, and interior decorations. -

A Garden of Story and Mystery

AVALON A Garden of Story and netted wall and canopy Mystery up lawn up up pavilion water garden view from herb garden to pavilion and water garden herb garden viewing pond ramp The wall inspires an experience of boundary as well as of guidance; it both separates us from the outside and provides a reference to the change in topography. At the same time it encloses the space of the garden and guides one throughout the space. The Garden is a place of story and mystery; a juxtaposition of different elements to provide internal and external experience at multiple scales. At the scale of the landscape there is the ramp which provides a view across the estate and an intimate experience of the wall through touch, while the pond is the opposite, prompting one to look down into the water and into the space below the wall. At the scale of the garden, there is a dialogue between the heaviness of the wall to support plant growth and the ephemeral net which changes from wall to canopy and allows one to see the plants as a fi lter instead of as an object. At the human scale, the pavilion provides shelter and venue while the suspended water garden presents plants contained within glass vessels at varying heights for viewing by children and adults alike. The goal of the garden is to create a dynamic experience for both the gardener and the public. view from herb garden to viewing platform WRITTEN HISTORY, PERSONAL RECOLLECTION AND THE COMMUNAL SPACE OF THE GARDEN: THE HADSPEN PARABOLA A garden is a place where the natural becomes sculpted, set aside and put on display. -

The Western Historical

The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine INDEX Volume 54 1971 Published quarterly by THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA 4338 Bigelow Boulevard, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania A American Place Names, A Concise and Se- lective Dictionary for the Continental "Account of the Pennsylvania Railroad Riots, United States of America, by George R. from a Young Girl's Diary," by Helen Stewart, rev., 426-427 Crombie, ed. by John Newell Crombie, 385-389 Amish, migrated from eastern Pennsylvania Acropolis Plan, design University to MifflinCounty (1790), then to Somerset for of and counties, 67; migra- Pittsburgh, Palmer and Hornbostel, archi- Lawrence reverse tects, 182 tion from Ohio to Lawrence County, Pa., Addendum, to provide agricultural land for children, concerning Mrs. Margaret P. ; County, Bothwell's contributions to WPHM, 123 74 remove fromOhio to Jefferson Akeley, village in Pine Grove Township, Pa. (1962), to obtain better prices for land, Warren County, named after Levi Akeley, Jr., 15 Amish groups move to Holmes, Wayne, Alcuin, Utopian settlement near Lander, Logan, and Champaign counties, Ohio, dur- Farmington Township, named for English ing 1800s, 67 scholar, devoted to crafts and agriculture Andrew Carnegie, by Joseph Frazier Wall, (1940) ;many drafted in World War IIor commentary on, 110-118 went into industry, 16 Andrews, J. Cutler, background forinterest in Alden, Timothy, New Englander, a Congre- writing about old newspapers, 1-2; "Writ- gational minister, who founded Allegheny ing History from Civil War Newspapers," College, 73 1-14; research experiences in writingabout Alexander, Dr. Thomas Rush, commemora- Civil War newspapers ;many lucky finds ; tion gift from Robert D. Christie, 384 philosophy for writing history, 3-5 ; The Allegheny County, earliest settlers in, were South Reports the Civil War, rev., 77-78; Pennsylvania Germans ;soon outnumbered rev. -

OPTIONAL GROUP ACTIVITIES NYU Radiology in Santa Barbara Four Seasons, Santa Barbara October 19-23, 2009

OPTIONAL GROUP ACTIVITIES NYU Radiology in Santa Barbara Four Seasons, Santa Barbara October 19-23, 2009 The activities below have been arranged by TPI on an exclusive basis for NYU attendees so as not to conflict with the meeting agenda. TPI reserves the right to cancel or re-price any tours that do not meet the minimum requirements. Some activities require a commitment a month prior. Request after this date cannot be guaranteed. MONDAY, OCTOBER 19, 2009 ►Enchanted Santa Barbara 1:30pm-5:00pm $81 per adult $78 per child (5-18 years) Santa Barbara is one of the most beautiful small cities in the world. Guests invariably feel transported to a magical time and place in this city filled with unique architecture and relaxed vibes. Begin this unique tour by visiting Old Mission Santa Barbara, which is known as the Queen of the California Missions. The Mission’s sanctuary and chapel are still in use today, as is the Sacred Garden, which used to be closed to female visitors, with the exception of royalty or political wives, until 1959! After touring the Mission, head towards downtown Santa Barbara. The best way to discover the city is by following the steps of the famed “Red Tile” walking tour, which is a pleasant walk through just 12 short blocks in downtown Santa Barbara. Along the way, discover many of the city's oldest and most fascinating landmarks such as the Santa Barbara County Courthouse. This castle-like Spanish-Mediterranean stucco building lies in the center of Santa Barbara as a gleaming, glorious piece of architecture. -

Philadelphia World Heritage Tool Kit's Goal: Philadelphia’S Heritage Is Our Legacy from the Past and Home of Religious Freedom, Tolerance and Democracy

This is an interactive pdf! Click links for more info! PHILADELPHIA WORLD HERITAGE TOOL KIT 2 Dear Educator: Welcome to the first edition of the Philadelphia World Heritage Tool Kit! This document is a product of a joint venture between Global Philadelphia Association, the City of Philadelphia, and the University of Pennsylvania’s South Asia Center, Middle East Center and Center for East Asian Studies. The content of this document was created by Greater Philadelphia teachers just like you! The Tool Kit is designed for varied grades and subjects in K-12 as a vehicle and idea-starter for teaching the value of World Heritage to our children. The City of Philadelphia has for the past three years been engaged in a process for Philadelphia to become a World Heritage City. We are hopeful that this will transpire in November 2015 when the Organization of World Heritage Cities meets in Arequipa, Peru. For more information on the World Heritage City initiative and to support these efforts visit http://worldheritagephl.org/ We hope you find value in this collection of ideas and are able to transmit the message of Philadelphia as A World Heritage City to many minds and generations. Sincerely, Sylvie Gallier Howard Deputy Chief of Staff Commerce Department Zabeth Teelucksingh Executive Director Global Philadelphia Association 3 + Re-Imaging Our Heritage…. It is clear that young people in the United past through their own wonderfully States may have access to more creative approaches to a myriad of topics information about the world around and themes across grade level and them, their transnational community, discipline.