Deanripa-Geographicaldistribution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

i TABLE OF CONTENTS Editorial Board, Taxonomic Board . 5 Social Media Team, Country Representatives, Layout and Design, Our Cover Image . 6 ARTICLES Introductory Page . 7 Taxonomic revision of the Norops tropidonotus complex (Squamata, Dactyloidae), with the resurrection of N. spilorhipis (Álvarez del Toro and Smith, 1956) and the description of two new species . GUNTHER KÖHLER, JOSIAH H. TOWNSEND, AND CLAUS BO P. PETERSEN . 8 Introductory Page . 42 The herpetofauna of Tamaulipas, Mexico: composition, distribution, and conservation status . SERGIO A. TERÁN-JUÁREZ, ELÍ GARCÍA PADILLA, VICENTE MATA-SILVA, JERRY D. JOHNSON, AND LARRY DAVID WILSON. 43 Introductory Page . 114 New distribution record and reproductive data for the Chocoan Bushmaster, Lachesis acrochorda (Serpentes: Viperidae), in Panama . ROGEMIF DANIEL FUENTES AND GREIVIN CORRALES. 115 OTHER CONTRIBUTIONS Nature Notes . 128 Another surviving population of the Critically Endangered Atelopus varius (Anura: Bufonidae) in Costa Rica . CÉSAR L. BARRIO-AMORÓS AND JUAN ABARCA. 128 Thanatosis in four poorly known toads of the genus Incilius (Amphibia: Anura) from highlands of Costa Rica . KATHERINE SÁNCHEZ PANIAGUA AND JUAN G. ABARCA. 135 Crocodylus acutus (Cuvier, 1807) . Predation on a Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis) in the ocean . VÍCTOR J. ACOSTA-CHAVES, KEVIN R. RUSSELL, AND CADY SARTINI. 140 Abronia graminea (Cope, 1864) . Color variant . ADAM G. CLAUSE, GUSTAVO JIMÉNEZ-VELÁZQUEZ, AND HIBRAIM A. PÉREZ-MENDOZA . 142 Gonatodes albogularis. Predation by a Barred Puffbird (Nystalus radiatus) . RSL ÁNGEL SOSA-BARTUANO AND RAFAEL LAU . 146 Norops rodriguezii . Predation . CHRISTIAN M. GARCÍA-BALDERAS, J. ROGELIO CEDEÑO-VÁZQUEZ, AND RAYMUNDO MINEROS-RAMÍREZ . 147 Mesoamerican Herpetology 1 March 2016 | Volume 3 | Number 1 Seasonal polymorphism in male coloration of Sceloporus aurantius. -

Programa Nacional Para La Conservación De Las Serpientes Presentes En Colombia

PROGRAMA NACIONAL PARA LA CONSERVACIÓN DE LAS SERPIENTES PRESENTES EN COLOMBIA PROGRAMA NACIONAL PARA LA CONSERVACIÓN DE LAS SERPIENTES PRESENTES EN COLOMBIA MINISTERIO DE AMBIENTE Y DESARROLLO SOSTENIBLE AUTORES John D. Lynch- Prof. Instituto de Ciencias Naturales. PRESIDENTE DE LA REPÚBLICA DE COLOMBIA Teddy Angarita Sierra. Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Yoluka ONG Juan Manuel Santos Calderón Francisco Javier Ruiz-Gómez. Investigador. Instituto Nacional de Salud MINISTRO DE AMBIENTE Y DESARROLLO SOSTENIBLE Luis Gilberto Murillo Urrutia ANÁLISIS DE INFORMACIÓN GEOGRÁFICA VICEMINISTRO DE AMBIENTE Jhon A. Infante Betancour. Carlos Alberto Botero López Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Yoluka ONG DIRECTORA DE BOSQUES, BIODIVERSIDAD Y SERVICIOS FOTOGRAFÍA ECOSISTÉMICOS Javier Crespo, Teddy Angarita-Sierra, John D. Lynch, Luisa F. Tito Gerardo Calvo Serrato Montaño Londoño, Felipe Andrés Aponte GRUPO DE GESTIÓN EN ESPECIES SILVESTRES DISEÑO Y DIAGRAMACIÓN Coordinadora Johanna Montes Bustos, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales Beatriz Adriana Acevedo Pérez Camilo Monzón Navas, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales Profesional Especializada José Roberto Arango, MinAmbiente Claudia Luz Rodríguez CORRECCIÓN DE ESTILO María Emilia Botero Arias MinAmbiente INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE SALUD Catalogación en Publicación. Ministerio de Ambiente DIRECTORA GENERAL y Desarrollo Sostenible. Grupo de Divulgación de Martha Lucía Ospina Martínez Conocimiento y Cultura Ambiental DIRECTOR DE PRODUCCIÓN Néstor Fernando Mondragón Godoy GRUPO DE PRODUCCIÓN Y DESARROLLO Colombia. Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Francisco Javier Ruiz-Gómez Sostenible; Universidad Nacional de Colombia; Colombia. Instituto Nacional de Salud Programa nacional para la conservación de las serpientes presentes en Colombia / John D. Lynch; Teddy Angarita Sierra -. Instituto de Ciencias Naturales; Francisco J. Ruiz - Instituto Nacional de Salud Bogotá D.C.: Colombia. Ministerio de Ambiente y UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE COLOMBIA Desarrollo Sostenible, 2014. -

For Specific Identification of Lachesis Acrochorda Venom

The Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases ISSN 1678-9199 | 2012 | volume 18 | issue 2 | pages 173-179 Development of a sensitive enzyme immunoassay (ELISA) for specific ER P identification of Lachesis acrochorda venom A P Núñez Rangel V (1, 2), Fernández Culma M (1), Rey-Suárez P (1), Pereañez JA (1, 3) RIGINAL O (1) Program of Ophidism and Scorpionism, University of Antioquia, Medellin, Colombia; (2) School of Microbiology, University of Antioquia, Medellin, Colombia; (3) School of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, University of Antioquia, Medellin, Colombia. Abstract: The snake genus Lachesis provokes 2 to 3% of snakebites in Colombia every year. Two Lachesis species, L. acrochorda and L. muta, share habitats with snakes from another genus, namely Bothrops asper and B. atrox. Lachesis venom causes systemic and local effects such as swelling, hemorrhaging, myonecrosis, hemostatic disorders and nephrotoxic symptoms similar to those induced by Bothrops, Portidium and Bothriechis bites. Bothrops antivenoms neutralize a variety of Lachesis venom toxins. However, these products are unable to avoid coagulation problems provoked by Lachesis snakebites. Thus, it is important to ascertain whether the envenomation was caused by a Bothrops or Lachesis snake. The present study found enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) efficient for detecting Lachesis acrochorda venom in a concentration range of 3.9 to 1000 ng/mL, which did not show a cross-reaction with Bothrops, Portidium, Botriechis and Crotalus venoms. Furthermore, one fraction of L. acrochorda venom that did not show cross- reactivity with B. asper venom was isolated using the same ELISA antibodies; some of its proteins were identified including one Gal-specific lectin and one metalloproteinase. -

2020 Dis Malima.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO CEARÁ FACULDADE DE MEDICINA DEPARTAMENTO DE FISIOLOGIA E FARMACOLOGIA PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM FARMACOLOGIA MIKAEL ALMEIDA LIMA POTENCIAL NEFROPROTETOR DOS ÁCIDOS URSÓLICO E OLEANÓLICO NA INJÚRIA RENAL AGUDA INDUZIDA PELO VENENO DA SERPENTE Bothrops jararacussu FORTALEZA-CE 2020 MIKAEL ALMEIDA LIMA POTENCIAL NEFROPROTETOR DOS ÁCIDOS URSÓLICO E OLEANÓLICO NA INJÚRIA RENAL AGUDA INDUZIDA PELO VENENO DA SERPENTE Bothrops jararacussu Dissertação apresentada à Coordenação do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Farmacologia da Universidade Federal do Ceará como requisito para obtenção do título de Mestre em Farmacologia. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Alexandre Havt Bindá FORTALEZA-CE 2020 MIKAEL ALMEIDA LIMA POTENCIAL NEFROPROTETOR DOS ÁCIDOS URSÓLICO E OLEANÓLICO NA INJÚRIA RENAL AGUDA INDUZIDA PELO VENENO DA SERPENTE Bothrops jararacussu Dissertação apresentada à Coordenação do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Farmacologia da Universidade Federal do Ceará como requisito para obtenção do título de Mestre em Farmacologia. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Alexandre Havt Bindá Aprovada em: 20/02/2020 BANCA EXAMINADORA _____________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Alexandre Havt Bindá (Orientador) Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC) _____________________________________________________ Prof.ª Dr.ª Alice Maria Costa Martins (Titular) Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC) _____________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Bruno Andrade Cardi (Titular) Universidade Estadual do Ceará (UECE) _____________________________________________________ -

Reptiles of Ecuador: a Resource-Rich Online Portal, with Dynamic

Offcial journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 13(1) [General Section]: 209–229 (e178). Reptiles of Ecuador: a resource-rich online portal, with dynamic checklists and photographic guides 1Omar Torres-Carvajal, 2Gustavo Pazmiño-Otamendi, and 3David Salazar-Valenzuela 1,2Museo de Zoología, Escuela de Ciencias Biológicas, Pontifcia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Avenida 12 de Octubre y Roca, Apartado 17- 01-2184, Quito, ECUADOR 3Centro de Investigación de la Biodiversidad y Cambio Climático (BioCamb) e Ingeniería en Biodiversidad y Recursos Genéticos, Facultad de Ciencias de Medio Ambiente, Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Machala y Sabanilla EC170301, Quito, ECUADOR Abstract.—With 477 species of non-avian reptiles within an area of 283,561 km2, Ecuador has the highest density of reptile species richness among megadiverse countries in the world. This richness is represented by 35 species of turtles, fve crocodilians, and 437 squamates including three amphisbaenians, 197 lizards, and 237 snakes. Of these, 45 species are endemic to the Galápagos Islands and 111 are mainland endemics. The high rate of species descriptions during recent decades, along with frequent taxonomic changes, has prevented printed checklists and books from maintaining a reasonably updated record of the species of reptiles from Ecuador. Here we present Reptiles del Ecuador (http://bioweb.bio/faunaweb/reptiliaweb), a free, resource-rich online portal with updated information on Ecuadorian reptiles. This interactive portal includes encyclopedic information on all species, multimedia presentations, distribution maps, habitat suitability models, and dynamic PDF guides. We also include an updated checklist with information on distribution, endemism, and conservation status, as well as a photographic guide to the reptiles from Ecuador. -

Endemism on a Threatened Sky Island

Offcial journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 14(2) [General Section]: 27–46 (e237). Endemism on a threatened sky island: new and rare species of herpetofauna from Cerro Chucantí, Eastern Panama 1,2,3Abel Batista, 2,4,*Konrad Mebert, 2Madian Miranda, 2Orlando Garcés, 2Rogemif Fuentes, and 5Marcos Ponce 1ADOPTA El Bosque PANAMÁ 2Los Naturalistas, P.O. Box 0426-01459 David, Chiriquí, PANAMÁ 3Universidad Autónoma de Chiriquí, Ciudad Universitaria El Cabrero David, Chiriquí, 427, PANAMÁ 4Programa de Pós-graduação em Zoologia, Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz, Rodovia Jorge Amado, Km 16, 45662-900, Ilhéus, Bahia, BRAZIL 5Museo Herpetológico de Chiriquí, PANAMÁ Abstract.—Cerro Chucantí in the Darién province is the highest peak in the Majé Mountains, an isolated massif in Eastern Panama. In addition to common herpetological species such as the Terraranas, Pristimantis cruentus, and P. caryophyllaceus, rare species such as Pristimantis moro and Strabomantis bufoniformis occur as well. Recent expeditions to Cerro Chucantí revealed a remarkably rich diversity of 41 amphibian (19% of the total in Panama) and 35 reptile (13% of the total in Panama) species, including new and endemic species such as a salamander, Bolitoglossa chucantiensis, a frog Diasporus majeensis, and a snake, Tantilla berguidoi. Here, an up-to-date summary is presented on the herpetological species observed on this sky island (an isolated mountain habitat with endemic species), including several species without defnitive taxonomic allocation, new elevation records, and an analysis of species diversity. Keywords. Amphibians, community, diversity, evaluation, integrative taxonomy, premontane, reptiles, surveys Resumen.—El Cerro Chucantí en la provincia de Darién es el pico más alto de las montañas de la serranía de Majé, un macizo aislado en el este de Panamá. -

Disorders on Cardiovascular Parameters in Rats and in Human Blood Cells Caused by Lachesis Acrochorda Snake Venom

Toxicon 184 (2020) 180–191 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Toxicon journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/toxicon Disorders on cardiovascular parameters in rats and in human blood cells caused by Lachesis acrochorda snake venom Karen Leonor Angel-Camilo a,b, Jimmy Alexander Guerrero-Vargas b, Emanuella Feitosa de Carvalho a, Karine Lima-Silva a, Rodrigo Jos�e Bezerra de Siqueira a, Lyara Barbosa Nogueira Freitas c, Joao~ Antonio^ Costa de Sousa c, Mario Rog�erio Lima Mota a, Arm^enio Aguiar dos Santos a, Ana Gisele da Costa Neves-Ferreira d, Alexandre Havt a, Luzia Kalyne Almeida Moreira Leal c, Pedro Jorge Caldas Magalhaes~ a,* a Departamento de Fisiologia e Farmacologia, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade Federal Do Ceara,� Fortaleza, Ceara,� Brazil b Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Exactas y de la Educacion,� Departamento de Biología, Centro de Investigaciones Biom�edicas-Bioterio, Grupo de Investigaciones Herpetologicas� y Toxinologicas,� Universidad del Cauca, Popayan,� Colombia c Centro de Estudos Farmac^euticos e Cosm�eticos, Faculdade de Farmacia,� Odontologia e Enfermagem, Universidade Federal Do Ceara,� Fortaleza, Ceara,� Brazil d Laboratorio� de Toxinologia, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Fiocruz, Fiocruz, Av. Brasil 4365, Manguinhos, Rio de Janeiro, 21040-900, Brazil ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: In Colombia, Lachesis acrochorda causes 2–3% of all snake envenomations. The accidents promote a high mor Snake venom tality rate (90%) due to blood and cardiovascular complications. Here, the effects of the snake venom of Lachesis L. acrochorda (SVLa) were analyzed on human blood cells and on cardiovascular parameters of rats. SVLa platelet Aggregation induced blood coagulation, as measured by the prothrombin time test, but did not reduce the cell viability of Vasodilation neutrophils and platelets evaluated by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) Hypotension reduction assay and by the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) enzyme assay. -

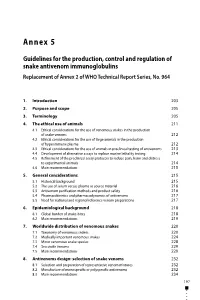

Guidelines for the Production, Control and Regulation of Snake Antivenom Immunoglobulins Replacement of Annex 2 of WHO Technical Report Series, No

Annex 5 Guidelines for the production, control and regulation of snake antivenom immunoglobulins Replacement of Annex 2 of WHO Technical Report Series, No. 964 1. Introduction 203 2. Purpose and scope 205 3. Terminology 205 4. The ethical use of animals 211 4.1 Ethical considerations for the use of venomous snakes in the production of snake venoms 212 4.2 Ethical considerations for the use of large animals in the production of hyperimmune plasma 212 4.3 Ethical considerations for the use of animals in preclinical testing of antivenoms 213 4.4 Development of alternative assays to replace murine lethality testing 214 4.5 Refinement of the preclinical assay protocols to reduce pain, harm and distress to experimental animals 214 4.6 Main recommendations 215 5. General considerations 215 5.1 Historical background 215 5.2 The use of serum versus plasma as source material 216 5.3 Antivenom purification methods and product safety 216 5.4 Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antivenoms 217 5.5 Need for national and regional reference venom preparations 217 6. Epidemiological background 218 6.1 Global burden of snake-bites 218 6.2 Main recommendations 219 7. Worldwide distribution of venomous snakes 220 7.1 Taxonomy of venomous snakes 220 7.2 Medically important venomous snakes 224 7.3 Minor venomous snake species 228 7.4 Sea snake venoms 229 7.5 Main recommendations 229 8. Antivenoms design: selection of snake venoms 232 8.1 Selection and preparation of representative venom mixtures 232 8.2 Manufacture of monospecific or polyspecific antivenoms 232 8.3 Main recommendations 234 197 WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization Sixty-seventh report 9. -

Dialogues on the Tao* of Lachesis * Tao: “The Way” in Literal Translation

Bull. Chicago Herp. Soc. 43(10):157-164, 2008 Dialogues on the Tao* of Lachesis * Tao: “the way” in literal translation. Taoism is an ancient Chinese school of thought that advocates open mind to all possibilities, in the same way that “the uncarved block” presents itself to the sculptor. Earl Turner 1, Rob Carmichael 2 and Rodrigo Souza 3 Introduction species. For Lachesis, so far the clearly demarcated taxa, which we call species, are L. acrochorda, L. melanocephala, L. muta Deep in the Atlantic rainforest in Brazil, at the Serra Grande and L. stenophrys. Subdividing L. muta into L. m. muta and L. Center (SG), a series of chicken wire, outdoor enclosures with m. rhombeata is in taxonomic limbo and under major contro- various natural vegetation, artificial burrows/retreats and expo- versy (Ripa, 2000–2006; Fernandes et al., 2004). The present sure to the natural elements has provided Dr. Rodrigo Souza edition of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature with the opportunity to successfully raise and breed Lachesis (Fourth Edition, ISBN 053301-006-4), however, does maintain muta rhombeata. Although seemingly “primitive” (from now trinominal nomenclature (subspecies). on PH, for Primitive Herpetoculture) by today’s highly techno- logical standards of captive care, it behooves us to consider The feeding challenge looking outside the box in terms of proper captive care of sensi- tive species like Lachesis. Whoever wishes to be successful in maintaining these pit- vipers in captivity must begin by understanding the unique The three authors come from very different backgrounds with feeding habits and the natural eco-biology involved. -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Revista de Biología Tropical ISSN: 0034-7744 ISSN: 2215-2075 Universidad de Costa Rica Solórzano, Alejandro; Sasa, Mahmood Redescription of the snake Lachesis melanocephala (Squamata: Viperidae): Designation of a neotype, natural history, and conservation status Revista de Biología Tropical, vol. 68, no. 4, 2020, October-, pp. 1387-1400 Universidad de Costa Rica DOI: https://doi.org/10.15517/RBT.V68I4.42359 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=44966323031 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative ISSN Printed: 0034-7744 ISSN digital: 2215-2075 Redescription of the snake Lachesis melanocephala (Squamata: Viperidae): Designation of a neotype, natural history, and conservation status Alejandro Solórzano1* & Mahmood Sasa2 1. Museo de Zoología, Universidad de Costa Rica, Ciudad Universitaria Rodrigo Facio, San Pedro de Montes de Oca, San José, Costa Rica; [email protected] 2. Instituto Clodomiro Picado y Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, Ciudad Universitaria Rodrigo Facio, San Pedro de Montes de Oca, San José, Costa Rica; [email protected] * Correspondance Received 18-VI-2020. Corrected 18-VIII-2020. Accepted 11-IX-2020. ABSTRACT. Introduction: The Black-headed Bushmaster (Lachesis melanocephala) is a large venomous snake that inhabits tropical moist forest, wet forest, montane and premontane wet forest in Southwestern Costa Rica and extreme Western Panama. Objective: We assign a neotype for the species due to the loss of the original holotype and update the information on its geographical distribution, natural history, and conservation status. -

Species Description Taxonomy Distribution

Bushmaster Species Description Bushmasters are one of the largest vipers in the world. They are the longest vipers; while Gabon Vipers and Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnakes are the heaviest vipers in the world. There have been reports of bushmasters measuring up to 14 feet but it is more likely that 12 feet is the maximum length. Bushmasters are sexually dimorphic in size with males reaching larger sizes. Photo: Brian Eisele Bushmasters are incredibly beautiful snakes with a pinkish tan, orangish tan, reddish brown or yellowish color with a series of dark markings down the back. Younger snakes usually have a darker ground color and lighter marking on their back relative to adult animals. Overall, there is a great deal of variation in color within and among bushmaster species. However, there are some color differences such as melanocephal; having a very dark head. In addition, bushmasters found in Central America often have wider heads with blunter snouts while bushmasters in the Amazon, especially those in the Guiana Shield have a narrower lancehead shape to the head. The middorsal scales or scales that run down the middle of the back have raised knoblike keels. The keels get smaller as you go towards the tail. Bushmaster’s fangs can be over two inches long and rival the Gabon Viper for longest fang length in snakes. Taxonomy The bushmaster was first described by F. M. Daudin in 1803 and the genus name came from one of the Three Fates in Greek Mythology. Lachesis is a goddess that measures the thread of life or how long each person will live. -

Introducción

INTRODUCCIÓN Las hemoparásitosis, transmitida a ofidios, son uno de los principales grupos de enfermedades que acometen a las serpientes. Su presencia se considera un hallazgo incidental en algunas especies, sin embargo, pueden causar enfermedades como la anemia hemolítica. Entre los reptiles son comunes las Haemogregarinas, tripanosomas y Plasmodium. Se destacan por determinar elevadas tasas de morbilidad y mortalidad. En Ecuador y en otros países de Centroamérica las informaciones epidemiológicas son escasas, aunque la enfermedad esté presente en casi todas las áreas tropicales y subtropicales del país, siendo transmitida principalmente por garrapatas que es el hexoparásito más común en los ofidios. Los animales salvajes están expuestos a múltiples agentes infecciosos y parasitarios, entre ellos hemoparásitos, que son transmitidas por insectos hematófagos. En condiciones de cautiverio, contribuyen en los centros serpentarios donde los animales son mantenidos y favorece la exacerbación de muchas enfermedades. Especialmente causadas por parásitos sanguíneos. O'DWYER LH; MOÇO TC, TH BARRELLA, FC VILELA, RJ SILVA. 2003. (5) El éxito de la manutención de serpientes en cautiverio depende en gran medida del control de sus parásitos, puesto que estos interfieren en su desarrollo y bienestar. Generalmente, en condiciones favorables, los animales de vida libre presentan una relación de equilibrio con sus parásitos y raramente se enferman. En cautiverio esta resistencia adquirida se pierde, pues el animal cautivo presenta un mayor grado de estrés debido a varios factores, tales como: contacto con personas, proximidad con otros animales, manutención en espacios reducidos, manipulaciones médicas o por traslados y dietas inadecuadas, entre otros. ZAMUDIO, N Y M. RAMÍREZ. 2007. (4) Existen pocos estudios hematológicos en ofidios, sin embargo se han reportado las características morfológicas, de acuerdo a la tinción de las células sanguíneas.