Afghans in Iran: Migration Patterns and Aspirations No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

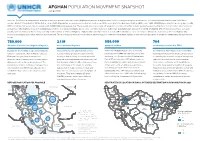

IRN Population Movement Snapshot June 2021

AFGHAN POPULATION MOVEMENT SNAPSHOT June 2021 Since the 1979 Soviet invasion and the subsequent waves of violence that have rocked Afghanistan, millions of Afghans have fled the country, seeking safety elsewhere. The Islamic Republic of Iran boasts 5,894 km of borders. Most of it, including the 921 km that are shared with Afghanistan, are porous and located in remote areas. While according to the Government of Iran (GIRI), some 1,400-2,500 Afghans arrive in Iran every day, recently GIRI has indicated increased daily movements with 4,000-5,000 arriving every day. These people aren’t necesserily all refugees, it is a mixed flow that includes people being pushed by the lack of economic opportunities as well as those who might be in need of international protection. The number fluctuates due to socio-economic challenges both in Iran and Afghanistan and also the COVID-19 situation. UNHCR Iran does not have access to border points and thus is unable to independently monitor arrivals or returns of Afghans. Afghans who currently reside in Iran have dierent statuses: some are refugees (Amayesh card holders), other are Afghans who posses a national passport, while other are undocumented. These populations move across borders in various ways. it is understood that many Afghans in Iran who have passports or are undocumented may have protection needs. 780,000 2.1 M 586,000 704 Amayesh Card Holders (Afghan refugees1) undocumented Afghans passport holders voluntarily repatriated in 2021 In 2001, the Government of Iran issues Amayesh Undocumented is an umbrella term used to There are 275,000 Afghans who hold family Covid-19 had a clear impact on the low VolRep cards to regularize the stay of Afghan refugees. -

A Community- Based Cross-Sectional Study

Deghatipour et al. BMC Oral Health (2019) 19:117 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-019-0801-x RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Oral health status in relation to socioeconomic and behavioral factors among pregnant women: a community- based cross-sectional study Marzie Deghatipour1 , Zahra Ghorbani2* , Shahla Ghanbari3, Shahnam Arshi4, Farnaz Ehdayivand5, Mahshid Namdari6 and Mina Pakkhesal7 Abstract Background: Oral health of women during pregnancy is an important issue. Not only it can compromise pregnancy outcomes, but also it may affect their newborn’s overall health. The aim of this study was to assess the oral health status and associated factors in pregnant women. Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted amongst 407 pregnant women in the second and third trimester of pregnancy in Varamin, Iran. Oral health status was examined, and demographic, socioeconomic status and dental care behavior data were collected. Oral health indices included periodontal pocket, bleeding on probing (BOP) and decayed, missed, filled teeth (DMFT). Regression analysis of DMFT was used to study the association between demographic, dental care behaviors indicators and outcome variables using the count ratios (CR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Results: The mean (SD, Standard Deviation) age of participants was 27.35 (5.57). Daily brushing, flossing habit were observed in 64.1, and 20.6% of mothers, respectively. Mean (SD) of DMFT, D, M, F were 10.34(5.10), 6.94(4.40), 2.22 (2.68) and 1.19(2.23), respectively. Women older than 35 years had significantly more DMFT [CR = 1.35 (95% CI 1.13; 1.60)], less D [CR = 0.75 (95% CI 0.59; 0.94)], and more M [CR = 3.63 (95% CI 2.57; 5.14)] compared to women under 25 years after controlling for education and dental care behaviors. -

REFUGEES Rn Lran* by Il Hobin Shorish University of Illinois At

Bismiallah THE AFGHAt! REFUGEES rn lRAN* by i.l. Hobin Shorish University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Throughout the recent histories of Iran and Afghanistan refugees of one form or another have existed in each of these lands. Political and religious refugees have almost always constituted the majority of those who sought either Afghanistan or Iran as their new haven. The most recent Iranian wave of refugees in the Khurasan area of Afghanistan (Herat) has been those who feared the develop-· ment of conflict in Iran between the super powers during the Second World War. Since, fortunately, such a conflict did not develop some of the Iranians who fled to Herat and other western provinces of Afghanistan returned to Iran and others '"'ettled in these areas, especially in Herat, to become citizens of the Afghan kin~dom. In all fonns of human transmigration it is the magnitude of the people moving that create problems often for the host countries. Therefore:, an in vestigation into the problems of the Afghan refugees in Iran, and the Iranians' attidude toward these refugees was needed for the benefit of those concerned uith the tragedy of Afghanistan and the brutality befalling the Afghan people by the Russians and their puppets in Kabul. The Afghan Refugees--~heir Number and Origins: Today, in Iran the magnitude of the Afghan refugees is unknmm. The refugees themselves are vague in their ansuers to the questions eliciting the number. They often articulate their answer in the following manner: "There are manyn~ "There are a lot of them";: "Afghans are scattered from Tabriz to Tayabad"; ''We are everywhere". -

Pdf 373.11 K

Journal of Language and Translation Volume 11, Number 4, 2021 (pp. 1-18) Adposition and Its Correlation with Verb/Object Order in Taleshi, Gilaki, and Tati Based on Dryer’s Typological Approach Farinaz Nasiri Ziba1, Neda Hedayat2*, Nassim Golaghaei3, Andisheh Saniei4 ¹ PhD Candidate of Linguistics, Roudehen Branch, Islamic Azad University, Roudehen, Iran ² Assistant Professor of Linguistics, Varamin-Pishva Branch, Islamic Azad University, Varamin, Iran ³ Assistant Professor of Applied Linguistics, Roudehen Branch, Islamic Azad University, Roudehen, Iran ⁴ Assistant Professor of Applied Linguistics, Roudehen Branch, Islamic Azad University, Roudehen, Iran Received: January 6, 2021 Accepted: May 9, 2021 Abstract This paper is a descriptive-analytic study on the adpositional system in a number of northwestern Iranian languages, namely Taleshi, Gilaki, and Tati, based on Dryer’s typological approach. To this end, the correlation of verb/object order was examined with the adpositional phrase and the results were compared based on the aforesaid approach. The research question investigated the correlation between adposition and verb/object order in each of these three varieties. First, the data collection was carried out through a semi-structured interview that was devised based on a questionnaire including a compilation of 66 Persian sentences that were translated into Taleshi, Gilaki, and Tati during interviews with 10 elderly illiterate and semi-literate speakers, respectively, from Hashtpar, Bandar Anzali, and Rostamabad of the Province of Gilan for each variety. Then, the transcriptions were examined in terms of diversity in adpositions, including two categories of preposition and postposition. The findings of the study indicated a strong correlation between the order of verbs and objects with postpositions. -

Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan

February 2002 Vol. 14, No. 2(G) AFGHANISTAN, IRAN, AND PAKISTAN CLOSED DOOR POLICY: Afghan Refugees in Pakistan and Iran “The bombing was so strong and we were so afraid to leave our homes. We were just like little birds in a cage, with all this noise and destruction going on all around us.” Testimony to Human Rights Watch I. MAP OF REFUGEE A ND IDP CAMPS DISCUSSED IN THE REPORT .................................................................................... 3 II. SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 III. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 IV. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................................................................................ 6 To the Government of Iran:....................................................................................................................................................................... 6 To the Government of Pakistan:............................................................................................................................................................... 7 To UNHCR :............................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Crown Agents Bank's Currency Capabilities

Crown Agents Bank’s Currency Capabilities August 2020 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Majors Australia Australian Dollar AUD ✓ ✓ - - M Canada Canadian Dollar CAD ✓ ✓ - - M Denmark Danish Krone DKK ✓ ✓ - - M Europe European Euro EUR ✓ ✓ - - M Japan Japanese Yen JPY ✓ ✓ - - M New Zealand New Zealand Dollar NZD ✓ ✓ - - M Norway Norwegian Krone NOK ✓ ✓ - - M Singapore Singapore Dollar SGD ✓ ✓ - - E Sweden Swedish Krona SEK ✓ ✓ - - M Switzerland Swiss Franc CHF ✓ ✓ - - M United Kingdom British Pound GBP ✓ ✓ - - M United States United States Dollar USD ✓ ✓ - - M Africa Angola Angolan Kwanza AOA ✓* - - - F Benin West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Botswana Botswana Pula BWP ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Burkina Faso West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cameroon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F C.A.R. Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Chad Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Cote D’Ivoire West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F DR Congo Congolese Franc CDF ✓ - - ✓ F Congo (Republic) Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Egypt Egyptian Pound EGP ✓ ✓ - - F Equatorial Guinea Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Eswatini Swazi Lilangeni SZL ✓ ✓ - - F Ethiopia Ethiopian Birr ETB ✓ ✓ N/A - F 1 Country Currency Code Foreign Exchange RTGS ACH Mobile Payments E/M/F Africa Gabon Central African Franc XAF ✓ ✓ ✓ - F Gambia Gambian Dalasi GMD ✓ - - - F Ghana Ghanaian Cedi GHS ✓ ✓ - ✓ F Guinea Guinean Franc GNF ✓ - ✓ - F Guinea-Bissau West African Franc XOF ✓ ✓ - - F Kenya Kenyan Shilling KES ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ F Lesotho Lesotho Loti LSL ✓ ✓ - - E Liberia Liberian -

Active Tectonics of Tehran Area, Iran

J. Basic. Appl. Sci. Res., 2(4)3805-3819, 2012 ISSN 2090-4304 Journal of Basic and Applied © 2012, TextRoad Publication Scientific Research www.textroad.com Active Tectonics of Tehran Area, Iran Mehran Arian1 *, Nooshin Bagha2 1Associate professor, Department of Geology, Science and Research branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran 2Ph.D.Student, Department of Geology, Science and Research branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran ABSTRACT Tehran area (with 2398.5 km2 area) extended from the east of Damavand volcano to the west of Karaj city. This area is a major part of Tehran province and according to geologic division is a minor part of Alborz zone. This area is under compressive stress and shortening that caused by Arabia – Eurasia Convergence. This situation has confirmed by dominant existence of folded structures and thrust fault system. We have investigated geologic hazards of Tehran area, because this area is the most strategic part of Iran. The major faults have been investigated and have not been found any evidences to existence of north and south Rey faults. In the other hand, active tectonic of this area has been investigated and Mosha fault has been introduced as the most active fault. The high seismic potential has been distinguished by integration of structural geology and active tectonic studies. The evaluation of movement potential of the main faults in the current tectonic regime shows the North Tehran fault has % 90 potential to movement. In addition the hazard potentials of landslides, settlements, volcanism and dams have been introduced. Finally, geologic hazard map has been prepared and has been divided to10 zones with one to four ranking of risk. -

List of Cities in Iran

S.No. Name of City 1 Abadan 2 Abadeh 3 Abyek 4 Abhar 5 Abyaneh 6 Ahar 7 Ahvaz 8 Alavicheh 9 Aligoodarz 10 Alvand 11 Amlash 12 Amol 13 Andimeshk 14 Andisheh 15 Arak 16 Ardabil 17 Ardakan 18 Asalem 19 Asalouyeh 20 Ashkezar 21 Ashlagh 22 Ashtiyan 23 Astaneh Arak 24 Astaneh-e Ashrafiyyeh 25 Astara 26 Babol 27 Babolsar 28 Baharestan 29 Balov 30 Bardaskan 31 Bam 32 Bampur 33 Bandar Abbas 34 Bandar Anzali 35 Bandar Charak 36 Bandar Imam 37 Bandar Lengeh 38 Bandar Torkman 39 Baneh 40 Bastak 41 Behbahan 42 Behshahr 43 Bijar 44 Birjand 45 Bistam 46 Bojnourd www.downloadexcelfiles.com 47 Bonab 48 Borazjan 49 Borujerd 50 Bukan 51 Bushehr 52 Damghan 53 Darab 54 Dargaz 55 Daryan 56 Darreh Shahr 57 Deylam 58 Deyr 59 Dezful 60 Dezghan 61 Dibaj 62 Doroud 63 Eghlid 64 Esfarayen 65 Eslamabad 66 Eslamabad-e Gharb 67 Eslamshahr 68 Evaz 69 Farahan 70 Fasa 71 Ferdows 72 Feshak 73 Feshk 74 Firouzabad 75 Fouman 76 Fasham, Tehran 77 Gachsaran 78 Garmeh-Jajarm 79 Gavrik 80 Ghale Ganj 81 Gerash 82 Genaveh 83 Ghaemshahr 84 Golbahar 85 Golpayegan 86 Gonabad 87 Gonbad-e Kavous 88 Gorgan 89 Hamadan 90 Hashtgerd 91 Hashtpar 92 Hashtrud 93 Heris www.downloadexcelfiles.com 94 Hidaj 95 Haji Abad 96 Ij 97 Ilam 98 Iranshahr 99 Isfahan 100 Islamshahr 101 Izadkhast 102 Izeh 103 Jajarm 104 Jask 105 Jahrom 106 Jaleq 107 Javanrud 108 Jiroft 109 Jolfa 110 Kahnuj 111 Kamyaran 112 Kangan 113 Kangavar 114 Karaj 115 Kashan 116 Kashmar 117 Kazeroun 118 Kerman 119 Kermanshah 120 Khalkhal 121 Khalkhal 122 Khomein 123 Khomeynishahr 124 Khonj 125 Khormuj 126 Khorramabad 127 Khorramshahr -

Country Codes and Currency Codes in Research Datasets Technical Report 2020-01

Country codes and currency codes in research datasets Technical Report 2020-01 Technical Report: version 1 Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre Harald Stahl Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 2 Abstract We describe the country and currency codes provided in research datasets. Keywords: country, currency, iso-3166, iso-4217 Technical Report: version 1 DOI: 10.12757/BBk.CountryCodes.01.01 Citation: Stahl, H. (2020). Country codes and currency codes in research datasets: Technical Report 2020-01 – Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre. 3 Contents Special cases ......................................... 4 1 Appendix: Alpha code .................................. 6 1.1 Countries sorted by code . 6 1.2 Countries sorted by description . 11 1.3 Currencies sorted by code . 17 1.4 Currencies sorted by descriptio . 23 2 Appendix: previous numeric code ............................ 30 2.1 Countries numeric by code . 30 2.2 Countries by description . 35 Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 4 Special cases From 2020 on research datasets shall provide ISO-3166 two-letter code. However, there are addi- tional codes beginning with ‘X’ that are requested by the European Commission for some statistics and the breakdown of countries may vary between datasets. For bank related data it is import- ant to have separate data for Guernsey, Jersey and Isle of Man, whereas researchers of the real economy have an interest in small territories like Ceuta and Melilla that are not always covered by ISO-3166. Countries that are treated differently in different statistics are described below. These are – United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland – France – Spain – Former Yugoslavia – Serbia United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. -

See the Document

IN THE NAME OF GOD IRAN NAMA RAILWAY TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN List of Content Preamble ....................................................................... 6 History ............................................................................. 7 Tehran Station ................................................................ 8 Tehran - Mashhad Route .............................................. 12 IRAN NRAILWAYAMA TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN Tehran - Jolfa Route ..................................................... 32 Collection and Edition: Public Relations (RAI) Tourism Content Collection: Abdollah Abbaszadeh Design and Graphics: Reza Hozzar Moghaddam Photos: Siamak Iman Pour, Benyamin Tehran - Bandarabbas Route 48 Khodadadi, Hatef Homaei, Saeed Mahmoodi Aznaveh, javad Najaf ...................................... Alizadeh, Caspian Makak, Ocean Zakarian, Davood Vakilzadeh, Arash Simaei, Abbas Jafari, Mohammadreza Baharnaz, Homayoun Amir yeganeh, Kianush Jafari Producer: Public Relations (RAI) Tehran - Goragn Route 64 Translation: Seyed Ebrahim Fazli Zenooz - ................................................ International Affairs Bureau (RAI) Address: Public Relations, Central Building of Railways, Africa Blvd., Argentina Sq., Tehran- Iran. www.rai.ir Tehran - Shiraz Route................................................... 80 First Edition January 2016 All rights reserved. Tehran - Khorramshahr Route .................................... 96 Tehran - Kerman Route .............................................114 Islamic Republic of Iran The Railways -

The Shifting Dynamics of International Reserve Currencies

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2019 The hiS fting Dynamics of International Reserve Currencies Robert Righi Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the International Economics Commons Recommended Citation Righi, Robert, "The hiS fting Dynamics of International Reserve Currencies" (2019). Honors Theses. 2342. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/2342 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Shifting Dynamics of International Reserve Currencies by Robert Righi * * * * * * * * * Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Departments of Economics and Mathematics UNION COLLEGE June 2019 Acknowledgement Thank you to both Professor Wang and Professor Motahar for their incredible support throughout the process of this work. The dedication to their students will forever be appreciated. This study would not have been at all possible without their guidance and thoughtful contributions. ii Abstract RIGHI, ROBERT J. - The Shifting Dynamics of International Reserve Currencies ADVISORS - Eshragh Motahar and Jue Wang Throughout most of post World War II period, the United States dollar has been globally accepted as the dominant reserve currency. This dominance comes with “exorbitant privilege” or special benefits such as not having a balance of payments problem. Therefore, with the shifting of global geopolitical balance of power in the age of Trump, along with the recognition by the IMF of the Chinese renminbi as an international reserve currency in 2015, it is important to understand the modern influence of reserve currencies. -

Water Dispute Escalating Between Iran and Afghanistan

Atlantic Council SOUTH ASIA CENTER ISSUE BRIEF Water Dispute Escalating between Iran and Afghanistan AUGUST 2016 FATEMEH AMAN Iran and Afghanistan have no major territorial disputes, unlike Afghanistan and Pakistan or Pakistan and India. However, a festering disagreement over allocation of water from the Helmand River is threatening their relationship as each side suffers from droughts, climate change, and the lack of proper water management. Both countries have continued to build dams and dig wells without environmental surveys, diverted the flow of water, and planted crops not suitable for the changing climate. Without better management and international help, there are likely to be escalating crises. Improving and clarifying existing agreements is also vital. The United States once played a critical role in mediating water disputes between Iran and Afghanistan. It is in the interest of the United States, which is striving to shore up the Afghan government and the region at large, to help resolve disagreements between Iran and Afghanistan over the Helmand and other shared rivers. The Atlantic Council Future Historical context of Iran Initiative aims to Disputes over water between Iran and Afghanistan date to the 1870s galvanize the international when Afghanistan was under British control. A British officer drew community—led by the United States with its global allies the Iran-Afghan border along the main branch of the Helmand River. and partners—to increase the In 1939, the Iranian government of Reza Shah Pahlavi and Mohammad Joint Comprehensive Plan of Zahir Shah’s Afghanistan government signed a treaty on sharing the Action’s chances for success and river’s waters, but the Afghans failed to ratify it.