Purpura Fulminans with Disseminated Intravascular Coagulopathy And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I, Paul Knoebl

Knoebl 2020-12-09 Public Declaration of Interests and Confidentiality Undertaking of European Medicines Agency (EMA), Scientific Committee members and experts Public declaration of interests I, Paul Knoebl Organisation/Company: Medical University of Vienna Country: Austria do hereby declare on my honour that, to the best of my knowledge, the only direct or indirect interests I have in the pharmaceutical industry are those listed below: 2.1 Employment No interest declared 2.2 Consultancy Period Company Products Therapeutic Indication 01/2009-(current) Novo Nordisk acquired hemophilia, congenital hemophilia, rare bleeding disorders 01/2012-02/2019 Baxalta (now Shire) thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura purpura fulminans acquired hemophilia 01/2012-01/2016 Alexion thrombotic microangiopathy 03/2010-07/2018 Ablynx thrombotic microangiopathy 07/2018-(current) Sanofi Genzyme thrombotic microangiopathy 02/2019-(current) Takeda thrombotic microangiopathy Acquired hemophilia 2.3 Strategic advisory role No interest declared 2.4 Financial interests Classified as public by the European Medicines Agency DOI Form Version-number: 4 Knoebl 2020-12-09 2 No interest declared 2.5 Principal investigator Period Company Products Therapeutic Indication 01/2013-(current) Baxalta, then Shire, now Takeda BAX930 Upshaw Schulman Syndrome 01/2013-(current) Novo Nordisc Concizumab Hemophilia 09/2010-04/2014 Gilead Ambisome fungal infections 09/2010-04/2014 MSD Posaconazol fungal infections 03/2010-(current) Ablynx caplacizumab thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura 04/2010-01/2012 -

Urticarial Vasculitis Associated with Essential Thrombocythaemia

Acta Derm Venereol 2014; 94: 244–245 SHORT COMMUNICATION Urticarial Vasculitis Associated with Essential Thrombocythaemia Annabel D. Scott, Nicholas Francis, Helen Yarranton and Sarita Singh Dermatology Registrar, Department of Dermatology, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, 369 Fulham Road, London SW10 9NH, United Kingdom. E-mail: [email protected] Accepted Apr 3, 2013; Epub ahead of print Aug 27, 2013 Urticarial vasculitis is a form of leucocytoclastic vas- prednisolone 30 mg once daily, which controlled her culitis whereby the skin lesions resemble urticaria. It is symptoms. associated with systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s A biopsy was taken from an uticarial lesion on the syndrome, hepatitis B and C viruses (1). Rarely it is asso- arm. Histology showed numerous perivascular neutro- ciated with an underlying haematological disorders and, phils and eosinophils with margination of neutrophils to the best of our knowledge, has never been reported in in the lumen of vessels and some leucocytoclasis with association with essential thrombocythaemia. We present red cell extravasation in keeping with an urticarial a case report of urticarial vasculitis associated with es- vasculitis (Fig. 2). sential thrombocythaemia. Blood tests revealed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 47 mm/h (normal range 1–12), a platelet count of 1,098 × 109/l (normal range 135–400) and an eosi- CASE REPORT nophilia of 1.0 × 109/l (normal range 0–0.2). Comple- A 32-year-old woman presented with a several month ment levels, thyroid function, serum iron, haemoglobin, history of recurrent urticaria without angioedema, 4 C-reactive protein, anti-nuclear antibody, anti-nuclear months post-partum. -

Extensive Purpura and Necrosis of the Leg

PHOTO CHALLENGE Extensive Purpura and Necrosis of the Leg Michael Musharbash, MD; Lida Zheng, MD; Lauren Guggina, MD A 57-year-old woman presented with expanding purpura on the left leg of 2 weeks’ duration following a recent hema- topoietic stem cell transplant for refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Prior to dermatologic consultation, the patient had been hospitalizedcopy for 2 months following the transplant due to Clostridium difficile colitis, Enterococcus faecium bactere- mia, cardiac arrest, delayed engraftment with pancytopenia, and atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome with acute renal failure requiring hemodialysis and treatment with eculizumab. Hernot care team in the hospital initially noticed a small purpuric lesion on the posterior aspect of the left knee. The patient subsequently developed persistent fevers and expansion of the lesion, which prompted consultation of the dermatology ser- vice. Physical examination revealed a 22×10-cm, rectangular, indurated, purpuric plaque with central dusky, violaceous to black necrosis with superficial skin sloughing and peripheral dusky erythema extending from the inner thigh to the lower leg. The left distal leg felt cool, and both dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses were absent. Laboratory test results revealed neutropenia and thrombocytopenia 3 3 Do 3 3 (white blood cell count, 0.2×10 /mm [reference range, 5–10×10 /mm ]; hematocrit, 23.2% [reference range, 41%–50%]; platelet count, 105×103/µL [reference range, 150–350×103/µL]). A punch biopsy was performed. WHAT’S THE DIAGNOSIS? a. disseminated aspergillosis b. disseminated intravascular coagulation c. disseminated mucormycosis d. purpura fulminans e. pyodermaCUTIS gangrenosum PLEASE TURN TO PAGE E2 FOR THE DIAGNOSIS From the Department of Dermatology, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago, Illinois. -

Appendix Search Strategy Treatment of Hemophilia.Pdf

Appendix Search strategies Hemophilia – general aspects PubMed (NLM) September 2009 Von Willebrand disease (TiAb) AND Controlled clinical trial (PT) NOT Purpura, Thrombocytopenic (Me) Angiohemophilia (TiAb) Meta analysis (PT) Blood coagulation disorders (Me) Randomized controlled trial (PT) Hemophilia (TiAb) Systematic (SB) Haemophilia (TiAb) Bleeding disorder (TiAb) Random* (Ti) Bleeding disorders (TiAb) OR Control* (Ti) NOT Medline (SB) ("controlled clinical trial"[Publication Type] OR "meta analysis"[Publication Type] OR "randomized controlled trial"[Publication Type] OR systematic[sb] OR ((random*[Title] OR control*[Title]) NOT Medline[sb])) AND ("von Willebrand Disease"[title/abstract] OR "angiohemophilia"[title/Abstract] OR "Blood Coagulation Disorders"[Mesh terms] OR "hemophilia"[title/abstract] OR "haemophilia"[title/abstract] OR "bleeding disorder"[title/abstract] OR "bleeding disorders"[Title/abstract]) NOT "Purpura, Thrombocytopenic"[MeSH Terms] 211 Hemophilia – general aspects Embase.com (Elsevier) September 2009 Blood clotting factor deficiency (Exp,MJR) AND Clinical trial (Exp) NOT Thrombocytopenic purpura (Exp) Von Willebrand disease (Ti) Intervention study (De) Angiohemophilia (Ti) Longitudinal study (De) Angiohaemophilia (Ti) Prospective study (De) Hemophilia (Ti) Meta analysis (De) Haemophilia (Ti) Systematic review (De) Bleeding disorder (Ti) Random* (Ti) Bleeding disorders (Ti) Control* (Ti) ('blood clotting factor deficiency'/exp/mjOR 'von willebrand disease':ti OR 'angiohemophilia':ti OR 'angiohaemophilia':ti OR 'hemophilia':ti -

Warfarin-Induced Skin Necrosis Due to Protein C Deficiency in a Dialysis Patient Diyaliz Hastasında Protein C Eksikliğine Bağlı Warfarin-İlişkili Deri Nekrozu

doi: 10.5262/tndt.2018.2775 Case Report/Olgu Sunumu Warfarin-Induced Skin Necrosis Due to Protein C Deficiency in a Dialysis Patient Diyaliz Hastasında Protein C Eksikliğine Bağlı Warfarin-İlişkili Deri Nekrozu ABSTRACT Abdullah ÖZKÖK1 Hande ÖZPORTAKAL1 Protein-C (PC) is a vitamin-K-dependent anticoagulant proenzyme produced by the liver. PC deficiency Murat AŞIK2 may cause both venous and arterial thromboses. In patients with PC deficiency, warfarin further 2 decreases PC activity and causes thrombosis of skin arterioles leading to skin necrosis. Serçin ÖZKÖK Özlem ALKAN1 A 59-year-old female was admitted with dyspnea, cough, hoarseness and edema in her neck and arms. Memduha BOYRAZ1 She had chronic kidney disease for 20 years. She had been on hemodialysis for 8 years but had been Gökhan GÖNENLI3 switched to peritoneal dialysis due to vascular access problems caused by multiple venous thromboses. Banu ŞAHIN YILDIZ1 With a pre-diagnosis of Superior Vena Cava (SVC) syndrome, cavography was performed and near- Kübra AYDIN BAHAT1 total occlusion of the SVC was detected. Balloon dilatation was performed and warfarin 5 mg and Ali Rıza ODABAŞ1 enoxoparin 40 mg were started. Within a day, necrotic and well-demarcated lesions 4x5 cm in size appeared on the arm. Warfarin was stopped and enoxoparin was continued. After 2 weeks, plasma PC activity was found to be significantly low (40% of normal). The diagnosis of “warfarin-induced skin necrosis in a patient with PC deficiency” was established. Skin lesions promptly and completely recovered after the treatment. 1 Istanbul Medeniyet University, PC deficiency should be considered in dialysis patients with multiple thromboses, vascular access Goztepe Training and Research Hospital, problems and warfarin-induced skin necrosis. -

Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura with Subsequent Development of JAK2 V617F-Positive Essential Thrombocythemia: Case Report

ISSN: 2640-7914 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.17352/ahcrr CLINICAL GROUP Received: 13 July, 2021 Case Report Accepted: 03 August, 2021 Published: 04 August, 2021 *Corresponding author: Marisabel Hurtado-Castillo, Immune thrombocytopenic PGY-3, Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine at NYU, 536 Ovington Avenue Apartment 3, Brooklyn NYC 11209, USA, Tel: 718-312-9641; purpura with subsequent Email: Keywords: Immune thrombocytopenic purpura; development of JAK2 Essential thrombocythemia; JAK-STAT signaling path- way; JAK2(V617F) mutation V617F-positive essential https://www.peertechzpublications.com thrombocythemia: Case Report Marisabel Hurtado-Castillo1*, Brian Flaherty2 and Morris Jrada2 1PGY-3, Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine at NYU, Brooklyn, NY, USA 2Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, Brooklyn, NY, USA Abstract The sequential occurrence of Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura (ITP) and Essential Thrombocythemia (ET) has been reported in the literature on a few occasions, as these are two hematologic disorders with distinct etiologies and patients usually have contrasting clinical presentations. Our case highlights the sequential occurrence of ITP, followed by Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) (V617F)-positive ET in a 64-year-old white woman, after four years of follow-up. The pathophysiology relating to these two conditions is incompletely understood, however, JAK2(V617F) mutation has been found in all the cases reported. Early identifi cation of JAK2(V617F) mutation in a patient with a -

Title 54 Pt Arial, Two Line Maximum

Benign Hematology Consult Cases Annemarie E. Fogerty, M.D. Clinical Director, Hematology Director, Reproductive Hematology Co-Medical Director, Anticoagulation Management Services September 2019 • No financial disclosures relevant to this presentation Case 1: 42yoF presenting with shortness of breath and productive cough Initial presentation • Vitals: T 99.2, HR 133, BP 145/75, RR 33, 92% sat on RA, improves to 95% with 2L 3 hours into presentation… Admitted to MICU • Vitals: T 100.8 , HR 140, BP 187/45, RR 45, 92% sat on 100% FiO2, 60L high-flow face mask 3 hours into MICU admission (6 hours from presentation) … • Vitals: Persistently febrile, T up to 105 • Respiratory status: O2 sat 80’s despite paralytics/vent adjustment, FiO2 1.0, inhaled flolan Case 1, continued: 4am in the MICU • Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is initiated ECMO has been shown to improve patient survival in acute respiratory distress, but associated with substantial hematologic derangements Lancet 2009; 374:1351 How does ECMO work? • An artificial lung (membrane oxygenator) oxygenates blood, which is returned to the circulation via the vein (VV) or artery (VA) – VV: artificial lung is in series with native lung, replacing lung function – VA: artificial lung is in parallel with native lung, replacing both heart and lung function • Blood exposure to the large ECMO circuit area – Initiates the contact factor pathway – Activates platelets – Induces an inflammatory response • Anticoagulation is necessary to prevent clotting the circuit – Intensity of anticoagulation, PTT/ACT have not correlated with clinical outcomes, or risk for bleeding/thrombosis Brodie D, Bacchetta M. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1905-1914. -

Thrombocytopenia.Pdf

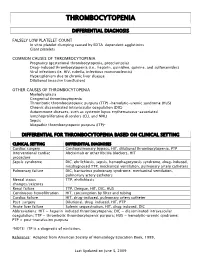

THROMBOCYTOPENIA DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS FALSELY LOW PLATELET COUNT In vitro platelet clumping caused by EDTA-dependent agglutinins Giant platelets COMMON CAUSES OF THROMBOCYTOPENIA Pregnancy (gestational thrombocytopenia, preeclampsia) Drug-induced thrombocytopenia (i.e., heparin, quinidine, quinine, and sulfonamides) Viral infections (ie. HIV, rubella, infectious mononucleosis) Hypersplenism due to chronic liver disease Dilutional (massive transfusion) OTHER CAUSES OF THROMBOCYTOPENIA Myelodysplasia Congenital thrombocytopenia Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) -hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) Chronic disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) Autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus-associated lymphoproliferative disorders (CLL and NHL) Sepsis Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP)* DIFFERENTIAL FOR THROMBOCYTOPENIA BASED ON CLINICAL SETTING CLINICAL SETTING DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES Cardiac surgery Cardiopulmonary bypass, HIT, dilutional thrombocytopenia, PTP Interventional cardiac Abciximab or other IIb/IIIa blockers, HIT procedure Sepsis syndrome DIC, ehrlichiosis, sepsis, hemophagocytosis syndrome, drug-induced, misdiagnosed TTP, mechanical ventilation, pulmonary artery catheters Pulmonary failure DIC, hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, mechanical ventilation, pulmonary artery catheters Mental status TTP, ehrlichiosis changes/seizures Renal failure TTP, Dengue, HIT, DIC, HUS Continuous hemofiltration HIT, consumption by filter and tubing Cardiac failure HIT, drug-induced, pulmonary artery catheter Post-surgery -

![PROTEIN C DEFICIENCY 1215 Adulthood and a Large Number of Children and Adults with Protein C Mutations [6,13]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8040/protein-c-deficiency-1215-adulthood-and-a-large-number-of-children-and-adults-with-protein-c-mutations-6-13-1348040.webp)

PROTEIN C DEFICIENCY 1215 Adulthood and a Large Number of Children and Adults with Protein C Mutations [6,13]

Haemophilia (2008), 14, 1214–1221 DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01838.x ORIGINAL ARTICLE Protein C deficiency N. A. GOLDENBERG* and M. J. MANCO-JOHNSON* *Hemophilia & Thrombosis Center, Section of Hematology, Oncology, and Bone Marrow Transplantation, Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado Denver and The ChildrenÕs Hospital, Aurora, CO; and Division of Hematology/ Oncology, Department of Medicine, University of Colorado Denver, Aurora, CO, USA Summary. Severe protein C deficiency (i.e. protein C ment of acute thrombotic events in severe protein C ) activity <1 IU dL 1) is a rare autosomal recessive deficiency typically requires replacement with pro- disorder that usually presents in the neonatal period tein C concentrate while maintaining therapeutic with purpura fulminans (PF) and severe disseminated anticoagulation; protein C replacement is also used intravascular coagulation (DIC), often with concom- for prevention of these complications around sur- itant venous thromboembolism (VTE). Recurrent gery. Long-term management in severe protein C thrombotic episodes (PF, DIC, or VTE) are common. deficiency involves anticoagulation with or without a Homozygotes and compound heterozygotes often protein C replacement regimen. Although many possess a similar phenotype of severe protein C patients with severe protein C deficiency are born deficiency. Mild (i.e. simple heterozygous) protein C with evidence of in utero thrombosis and experience deficiency, by contrast, is often asymptomatic but multiple further events, intensive treatment and may involve recurrent VTE episodes, most often monitoring can enable these individuals to thrive. triggered by clinical risk factors. The coagulopathy in Further research is needed to better delineate optimal protein C deficiency is caused by impaired inactiva- preventive and therapeutic strategies. -

ADAMTS13 in Arterial Thrombosis

ADAMTS13 in Arterial Thrombosis Tamara Bongers ADAMTS13 in Arterial Thrombosis © 2010 Tamara Bongers, Rotterdam, The Netherlands No part of this thesis may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission from the author or, when appropriate, from publishers of the publications. ISBN: 978-90-9025798-3 Cover design: Tamara Bongers Layout: Henri Wijnbergen and Tamara Bongers Printing: Ipskamp Drukkers, Enschede ADAMTS13 in Arterial Thrombosis ADAMTS13 in arteriële trombose Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam op gezag van de rector magnificus Prof.dr. H.G. Schmidt en volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties. De openbare verdediging zal plaatsvinden op donderdag 9 december 2010 om 11:30 uur door Tamara Natascha Bongers geboren te Zevenaar Promotiecommissie Promotor: Prof.dr. F.W.G. Leebeek Overige leden: Prof.dr. M.M.B. Breteler Prof.dr. D.W.J. Dippel Dr. T. Lisman Copromotor: Dr. M.P.M. de Maat The work described in this thesis was performed at the Deparment of Hematology of Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Nether- lands. This work was partly funded by MRACE Translational Research Grant ErasmusMC 2004 as a clinical fellow to F.W.G. Leebeek. Financial support by the Netherlands Heart Foundation for publication of this thesis is gratefully acknowledged. Printing of this thesis was financially supported by Baxter, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Jurriaanse Stichting, Kordia and Pfizer. “ The World is a book, and -

Acute Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura in Children

Turk J Hematol 2007; 24:41-51 REVIEW ARTICLE © Turkish Society of Hematology Acute immune thrombocytopenic purpura in children Abdul Rehman Sadiq Public School, Bahawalpur, Pakistan [email protected] Received: Sep 12, 2006 • Accepted: Mar 21, 2007 ABSTRACT Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) in children is usually a benign and self-limiting disorder. It may follow a viral infection or immunization and is caused by an inappropriate response of the immune system. The diagnosis relies on the exclusion of other causes of thrombocytopenia. This paper discusses the differential diagnoses and investigations, especially the importance of bone marrow aspiration. The course of the disease and incidence of intracranial hemorrhage are also discussed. There is substantial discrepancy between published guidelines and between clinicians who like to over-treat. The treatment of the disease ranges from observation to drugs like intrave- nous immunoglobulin, steroids and anti-D to splenectomy. The different modes of treatment are evaluated. The best treatment seems to be observation except in severe cases. Key Words: Thrombocytopenic purpura, bone marrow aspiration, Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, steroids, anti-D immunoglobulins 41 Rehman A INTRODUCTION There is evidence that enhanced T-helper cell/ Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) in APC interactions in patients with ITP may play an children is usually a self-limiting disorder. The integral role in IgG antiplatelet autoantibody pro- American Society of Hematology (ASH) in 1996 duction -

Painless Purple Streaks on the Arms and Chest

PHOTO CHALLENGE Painless Purple Streaks on the Arms and Chest Tiffany Alexander, MD; Bernard Cohen, MD A 10-year-old boy presented with painless purple streaks on the arms and chest of 2 months’ duration. The rash recurred several times per month and cleared without treatment in 3 to 5 days. There was no history of trauma or medication exposure, and he was growing and developing normally.copy WHAT’S THE DIAGNOSIS? a. child maltreatment syndrome b. notfactitial purpura c. Henoch-Schönlein purpura d. idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura Doe. meningococcemia PLEASE TURN TO PAGE E9 FOR THE DIAGNOSIS CUTIS Dr. Alexander was from the University of Maryland, Baltimore, and currently is from the Department of Dermatology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina. Dr. Cohen is from the Department of Dermatology, Division of Pediatric Dermatology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore. The authors report no conflict of interest. Correspondence: Bernard Cohen, MD, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of Pediatric Dermatology, David M. Rubenstein Child Health Bldg, Ste 2107, 200 N Wolfe St, Baltimore, MD 21287 ([email protected]). E8 I CUTIS® WWW.MDEDGE.COM/DERMATOLOGY Copyright Cutis 2019. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted without the prior written permission of the Publisher. PHOTO CHALLENGE DISCUSSION THE DIAGNOSIS: Factitial Purpura actitial dermatologic disorders are characterized by the state of one’s health and life span.4 Cupping is per- skin findings triggered by deliberate manipulation formed by placing a glass cup over a painful body part. F of the skin with objects to create lesions and feign A partial vacuum is created by flaming, mechanical with- signs of a dermatologic condition to seek emotional drawal, or thermal cooling of the entrapped air under the and psychological benefit.1 The etiology of the lesions is cup.