Acute Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura in Children

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Differentiating Between Anxiety, Syncope & Anaphylaxis

Differentiating between anxiety, syncope & anaphylaxis Dr. Réka Gustafson Medical Health Officer Vancouver Coastal Health Introduction Anaphylaxis is a rare but much feared side-effect of vaccination. Most vaccine providers will never see a case of true anaphylaxis due to vaccination, but need to be prepared to diagnose and respond to this medical emergency. Since anaphylaxis is so rare, most of us rely on guidelines to assist us in assessment and response. Due to the highly variable presentation, and absence of clinical trials, guidelines are by necessity often vague and very conservative. Guidelines are no substitute for good clinical judgment. Anaphylaxis Guidelines • “Anaphylaxis is a potentially life-threatening IgE mediated allergic reaction” – How many people die or have died from anaphylaxis after immunization? Can we predict who is likely to die from anaphylaxis? • “Anaphylaxis is one of the rarer events reported in the post-marketing surveillance” – How rare? Will I or my colleagues ever see a case? • “Changes develop over several minutes” – What is “several”? 1, 2, 10, 20 minutes? • “Even when there are mild symptoms initially, there is a potential for progression to a severe and even irreversible outcome” – Do I park my clinical judgment at the door? What do I look for in my clinical assessment? • “Fatalities during anaphylaxis usually result from delayed administration of epinephrine and from severe cardiac and respiratory complications. “ – What is delayed? How much time do I have? What is anaphylaxis? •an acute, potentially -

Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Successful Management of a Rare Presentation

Indian J Crit Care Med July-September 2008 Vol 12 Issue 3 Case Report Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and systemic lupus erythematosus: Successful management of a rare presentation Pratish George, Jasmine Das, Basant Pawar1, Naveen Kakkar2 Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) very rarely present simultaneously and pose a diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma to the critical care team. Prompt diagnosis and management with plasma exchange and immunosuppression is life-saving. A patient critically ill with TTP and SLE, successfully managed in the acute period of illness with plasma exchange, steroids and Abstract mycophenolate mofetil is described. Key words: Plasma exchange, systemic lupus erythematosus, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura Introduction Case Report Systemic lupus erythematosis (SLE) is diagnosed by A 30-year-old lady was admitted with fever and the presence of four or more of the following criteria, jaundice. A week earlier she had undergone an serially or simultaneously: malar rash, discoid rash, uncomplicated medical termination of pregnancy at photosensitivity, oral ulcers, non erosive arthritis, serositis, another hospital, at 13 weeks of gestation. She had an renal abnormalities including proteinuria or active urinary uneventful pregnancy with twins two years earlier and sediments, neuropsychiatric features, hematological the twins were diagnosed to have thalassemia major. abnormalities including hemolytic anemia, leucopenia, She was subsequently diagnosed to have thalassemia lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia, immunological minor and her husband had thalassemia minor trait. No markers like anti-ds DNA or anti-Smith antibody and high earlier history of spontaneous Þ rst trimester abortions Antinuclear antibody titres. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic was present. purpura (TTP) in patients with SLE is extremely rare. -

Urticarial Vasculitis Associated with Essential Thrombocythaemia

Acta Derm Venereol 2014; 94: 244–245 SHORT COMMUNICATION Urticarial Vasculitis Associated with Essential Thrombocythaemia Annabel D. Scott, Nicholas Francis, Helen Yarranton and Sarita Singh Dermatology Registrar, Department of Dermatology, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, 369 Fulham Road, London SW10 9NH, United Kingdom. E-mail: [email protected] Accepted Apr 3, 2013; Epub ahead of print Aug 27, 2013 Urticarial vasculitis is a form of leucocytoclastic vas- prednisolone 30 mg once daily, which controlled her culitis whereby the skin lesions resemble urticaria. It is symptoms. associated with systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s A biopsy was taken from an uticarial lesion on the syndrome, hepatitis B and C viruses (1). Rarely it is asso- arm. Histology showed numerous perivascular neutro- ciated with an underlying haematological disorders and, phils and eosinophils with margination of neutrophils to the best of our knowledge, has never been reported in in the lumen of vessels and some leucocytoclasis with association with essential thrombocythaemia. We present red cell extravasation in keeping with an urticarial a case report of urticarial vasculitis associated with es- vasculitis (Fig. 2). sential thrombocythaemia. Blood tests revealed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 47 mm/h (normal range 1–12), a platelet count of 1,098 × 109/l (normal range 135–400) and an eosi- CASE REPORT nophilia of 1.0 × 109/l (normal range 0–0.2). Comple- A 32-year-old woman presented with a several month ment levels, thyroid function, serum iron, haemoglobin, history of recurrent urticaria without angioedema, 4 C-reactive protein, anti-nuclear antibody, anti-nuclear months post-partum. -

Immune-Pathophysiology and -Therapy of Childhood Purpura

Egypt J Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2009;7(1):3-13. Review article Immune-pathophysiology and -therapy of childhood purpura Safinaz A Elhabashy Professor of Pediatrics, Ain Shams University, Cairo Childhood purpura - Overview vasculitic disorders present with palpable Purpura (from the Latin, purpura, meaning purpura2. Purpura may be secondary to "purple") is the appearance of red or purple thrombocytopenia, platelet dysfunction, discolorations on the skin that do not blanch on coagulation factor deficiency or vascular defect as applying pressure. They are caused by bleeding shown in table 1. underneath the skin. Purpura measure 0.3-1cm, A thorough history (Table 2) and a careful while petechiae measure less than 3mm and physical examination (Table 3) are critical first ecchymoses greater than 1cm1. The integrity of steps in the evaluation of children with purpura3. the vascular system depends on three interacting When the history and physical examination elements: platelets, plasma coagulation factors suggest the presence of a bleeding disorder, and blood vessels. All three elements are required laboratory screening studies may include a for proper hemostasis, but the pattern of bleeding complete blood count, peripheral blood smear, depends to some extent on the specific defect. In prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial general, platelet disorders manifest petechiae, thromboplastin time (aPTT). With few exceptions, mucosal bleeding (wet purpura) or, rarely, central these studies should identify most hemostatic nervous system bleeding; -

An Avoidable Cause of Thymoglobulin Anaphylaxis S

Brabant et al. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol (2017) 13:13 Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology DOI 10.1186/s13223-017-0186-9 CASE REPORT Open Access An avoidable cause of thymoglobulin anaphylaxis S. Brabant1*, A. Facon2, F. Provôt3, M. Labalette1, B. Wallaert4 and C. Chenivesse4 Abstract Background: Thymoglobulin® (anti-thymocyte globulin [rabbit]) is a purified pasteurised, gamma immune globulin obtained by immunisation of rabbits with human thymocytes. Anaphylactic allergic reactions to a first injection of thymoglobulin are rare. Case presentation: We report a case of serious anaphylactic reaction occurring after a first intraoperative injection of thymoglobulin during renal transplantation in a patient with undiagnosed respiratory allergy to rabbit allergens. Conclusions: This case report reinforces the importance of identifying rabbit allergy by a simple combination of clini- cal interview followed by confirmatory skin testing or blood tests of all patients prior to injection of thymoglobulin, which is formally contraindicated in patients with a history of hypersensitivity to rabbit proteins. Keywords: Thymoglobulin, Anaphylactic allergic reaction, Rabbit proteins Background [7]. Cases of serious anaphylactic reactions to thymo- Thymoglobulin is an IgG fraction purified from the globulin due to rabbit protein allergy are very rare, and serum of rabbits immunised against human thymocytes. consequently, specific tests for rabbit allergy are not The preparation consists of polyclonal antilymphocyte usually performed as part of the pre-transplant assess- IgG directed against T lymphocyte surface antigens, and ment. We report a case of serious anaphylactic reaction induction of profound lymphocyte depletion is though due to rabbit protein allergy following a first injection of to be the main mechanism of thymoglobulin-mediated thymoglobulin. -

Hypersensitivity Reactions (Types I, II, III, IV)

Hypersensitivity Reactions (Types I, II, III, IV) April 15, 2009 Inflammatory response - local, eliminates antigen without extensively damaging the host’s tissue. Hypersensitivity - immune & inflammatory responses that are harmful to the host (von Pirquet, 1906) - Type I Produce effector molecules Capable of ingesting foreign Particles Association with parasite infection Modified from Abbas, Lichtman & Pillai, Table 19-1 Type I hypersensitivity response IgE VH V L Cε1 CL Binds to mast cell Normal serum level = 0.0003 mg/ml Binds Fc region of IgE Link Intracellular signal trans. Initiation of degranulation Larche et al. Nat. Rev. Immunol 6:761-771, 2006 Abbas, Lichtman & Pillai,19-8 Factors in the development of allergic diseases • Geographical distribution • Environmental factors - climate, air pollution, socioeconomic status • Genetic risk factors • “Hygiene hypothesis” – Older siblings, day care – Exposure to certain foods, farm animals – Exposure to antibiotics during infancy • Cytokine milieu Adapted from Bach, JF. N Engl J Med 347:911, 2002. Upham & Holt. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 5:167, 2005 Also: Papadopoulos and Kalobatsou. Curr Op Allergy Clin Immunol 7:91-95, 2007 IgE-mediated diseases in humans • Systemic (anaphylactic shock) •Asthma – Classification by immunopathological phenotype can be used to determine management strategies • Hay fever (allergic rhinitis) • Allergic conjunctivitis • Skin reactions • Food allergies Diseases in Humans (I) • Systemic anaphylaxis - potentially fatal - due to food ingestion (eggs, shellfish, -

Anaphylaxis Following Administration of Extracorporeal Photopheresis for Cutaneous T Cell Lymphoma

Volume 26 Number 9| September 2020| Dermatology Online Journal || Letter 26(9):18 Anaphylaxis following administration of extracorporeal photopheresis for cutaneous T cell lymphoma Jessica Tran1,2, Lisa Morris3, Alan Vu4, Sampreet Reddy1, Madeleine Duvic1 Affiliations: 1Department of Dermatology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas, USA, 2Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA, 3University of Missouri Columbia School of Medicine, Columbia, Missouri , USA, 4University of Texas McGovern Medical School, Houston, Texas, USA Corresponding Author: Madeleine Duvic MD, Department of Dermatology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Unit 1452, 1515 Holcombe Boulevard, Houston, TX 77030, Tel: 713-792-6800, Email: [email protected] peripheral blood from a patient, (ii) separating the Abstract white blood cells from whole blood by Extracorporeal photopheresis is a non-invasive centrifugation, (iii) adding psoralen, a therapy used for the treatment of a range of T cell photosensitizing agent, to the white blood cells, (iv) disorders, including cutaneous T cell lymphoma. exposing the white blood cells to ultraviolet A (UVA) During extracorporeal photopheresis, peripheral radiation, and (v) re-infusing the treated white blood blood is removed from the patient and the white blood cells are separated from whole blood via cells to the patient [3]. The re-infusion of apoptotic centrifugation. The white blood cells are exposed to leukocytes triggers an immune response resulting in psoralen (a photosensitizing agent) and ultraviolet A production of CD8+ tumor suppressor cells in CTCL radiation, causing cell apoptosis. The apoptotic [3]. Extracorporeal photopheresis is generally leukocytes are subsequently re-infused into the regarded as safe with few side effects [3]. -

Appendix Search Strategy Treatment of Hemophilia.Pdf

Appendix Search strategies Hemophilia – general aspects PubMed (NLM) September 2009 Von Willebrand disease (TiAb) AND Controlled clinical trial (PT) NOT Purpura, Thrombocytopenic (Me) Angiohemophilia (TiAb) Meta analysis (PT) Blood coagulation disorders (Me) Randomized controlled trial (PT) Hemophilia (TiAb) Systematic (SB) Haemophilia (TiAb) Bleeding disorder (TiAb) Random* (Ti) Bleeding disorders (TiAb) OR Control* (Ti) NOT Medline (SB) ("controlled clinical trial"[Publication Type] OR "meta analysis"[Publication Type] OR "randomized controlled trial"[Publication Type] OR systematic[sb] OR ((random*[Title] OR control*[Title]) NOT Medline[sb])) AND ("von Willebrand Disease"[title/abstract] OR "angiohemophilia"[title/Abstract] OR "Blood Coagulation Disorders"[Mesh terms] OR "hemophilia"[title/abstract] OR "haemophilia"[title/abstract] OR "bleeding disorder"[title/abstract] OR "bleeding disorders"[Title/abstract]) NOT "Purpura, Thrombocytopenic"[MeSH Terms] 211 Hemophilia – general aspects Embase.com (Elsevier) September 2009 Blood clotting factor deficiency (Exp,MJR) AND Clinical trial (Exp) NOT Thrombocytopenic purpura (Exp) Von Willebrand disease (Ti) Intervention study (De) Angiohemophilia (Ti) Longitudinal study (De) Angiohaemophilia (Ti) Prospective study (De) Hemophilia (Ti) Meta analysis (De) Haemophilia (Ti) Systematic review (De) Bleeding disorder (Ti) Random* (Ti) Bleeding disorders (Ti) Control* (Ti) ('blood clotting factor deficiency'/exp/mjOR 'von willebrand disease':ti OR 'angiohemophilia':ti OR 'angiohaemophilia':ti OR 'hemophilia':ti -

How to Recognise and Manage Mild to Moderate Allergic Reactions in Children Information for Parents and Carers Contents Page What Is an Allergic Reaction? 2

Children’s Allergy Clinic How to recognise and manage mild to moderate allergic reactions in children Information for parents and carers Contents Page What is an allergic reaction? 2 What can cause allergic reactions? 3 How to avoid contact with allergens 4 Signs and symptoms 6 Action plan 7 Nurseries, child-minders, schools/activity groups 9 Further information 11 What is an allergic reaction? An allergic reaction happens when the body’s immune system over-reacts to contact with normally harmless substances. An allergic person’s immune system treats certain substances as threats and releases substances such as histamines to defend the body against them. The release of histamine can cause the body to produce a range of mild to severe symptoms. An allergic response can develop after touching, swallowing, tasting, eating or breathing-in a particular substance. page 2 What can cause allergic reactions? Foods For example: • nuts (especially peanuts) • fish and shellfish • eggs and milk. Most allergic reactions to food occur immediately after swallowing, although some can occur up to several hours afterwards. Food allergies are more common in families who have other allergic conditions such as asthma, eczema and hay fever. Rarely, people have an allergic reaction to fruit, vegetables and legumes. Legumes include pulses, beans, peas and lentils. Peanuts are also part of the legume family. Insect stings • Reaction to an insect sting is immediate (within 30 minutes). Natural rubber latex Some common sources of latex are: • balloons • rubber bands • carpet backing • furniture filling • medical or dental items such as catheters, gloves, disposable items. Medicines Medication rarely causes a severe allergic reaction in children. -

Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura with Subsequent Development of JAK2 V617F-Positive Essential Thrombocythemia: Case Report

ISSN: 2640-7914 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.17352/ahcrr CLINICAL GROUP Received: 13 July, 2021 Case Report Accepted: 03 August, 2021 Published: 04 August, 2021 *Corresponding author: Marisabel Hurtado-Castillo, Immune thrombocytopenic PGY-3, Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine at NYU, 536 Ovington Avenue Apartment 3, Brooklyn NYC 11209, USA, Tel: 718-312-9641; purpura with subsequent Email: Keywords: Immune thrombocytopenic purpura; development of JAK2 Essential thrombocythemia; JAK-STAT signaling path- way; JAK2(V617F) mutation V617F-positive essential https://www.peertechzpublications.com thrombocythemia: Case Report Marisabel Hurtado-Castillo1*, Brian Flaherty2 and Morris Jrada2 1PGY-3, Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine at NYU, Brooklyn, NY, USA 2Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, Brooklyn, NY, USA Abstract The sequential occurrence of Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura (ITP) and Essential Thrombocythemia (ET) has been reported in the literature on a few occasions, as these are two hematologic disorders with distinct etiologies and patients usually have contrasting clinical presentations. Our case highlights the sequential occurrence of ITP, followed by Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) (V617F)-positive ET in a 64-year-old white woman, after four years of follow-up. The pathophysiology relating to these two conditions is incompletely understood, however, JAK2(V617F) mutation has been found in all the cases reported. Early identifi cation of JAK2(V617F) mutation in a patient with a -

Thrombocytopenia.Pdf

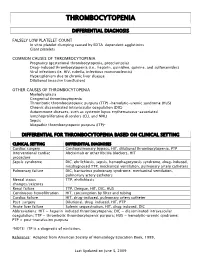

THROMBOCYTOPENIA DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS FALSELY LOW PLATELET COUNT In vitro platelet clumping caused by EDTA-dependent agglutinins Giant platelets COMMON CAUSES OF THROMBOCYTOPENIA Pregnancy (gestational thrombocytopenia, preeclampsia) Drug-induced thrombocytopenia (i.e., heparin, quinidine, quinine, and sulfonamides) Viral infections (ie. HIV, rubella, infectious mononucleosis) Hypersplenism due to chronic liver disease Dilutional (massive transfusion) OTHER CAUSES OF THROMBOCYTOPENIA Myelodysplasia Congenital thrombocytopenia Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) -hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) Chronic disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) Autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus-associated lymphoproliferative disorders (CLL and NHL) Sepsis Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP)* DIFFERENTIAL FOR THROMBOCYTOPENIA BASED ON CLINICAL SETTING CLINICAL SETTING DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES Cardiac surgery Cardiopulmonary bypass, HIT, dilutional thrombocytopenia, PTP Interventional cardiac Abciximab or other IIb/IIIa blockers, HIT procedure Sepsis syndrome DIC, ehrlichiosis, sepsis, hemophagocytosis syndrome, drug-induced, misdiagnosed TTP, mechanical ventilation, pulmonary artery catheters Pulmonary failure DIC, hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, mechanical ventilation, pulmonary artery catheters Mental status TTP, ehrlichiosis changes/seizures Renal failure TTP, Dengue, HIT, DIC, HUS Continuous hemofiltration HIT, consumption by filter and tubing Cardiac failure HIT, drug-induced, pulmonary artery catheter Post-surgery -

COVID-19 Vaccine and Allergy

COVID Vaccine and Allergy Stephanie Leonard, MD Associate Clinical Professor Department of Pediatric Allergy & Immunology January 20, 2020 Safe and Impactful • Proper Screening COVID Vaccine • Monitoring Administration • Clinical Assessment • Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) detected 21 cases of anaphylaxis after administration of a reported 1,893,360 first doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine • 11.1 cases per million doses (0.001%) • 1.3 cases per million for flu vaccines • 71% occurred within 15 min of vaccination, 86% within 30 minutes • Range = 2–150 minutes • Of 20 with follow-up info, all had recovered or been discharged home. • 17 (81%) with h/o allergies to food, vaccine, medication, venom, contrast, or pets. • 4 with no h/o any allergies • 7 with h/o anaphylaxis • Rabies vaccine • Flu vaccine • 19 (90%) diffuse rash or generalized hives Allergic Reactions Including Anaphylaxis After Receipt of the First Dose of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine — United States, December 14–23, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:46–51. Early Signs of Anaphylaxis • Respiratory: sensation of throat closing*, stridor, shortness of breath, wheeze, cough • Gastrointestinal: nausea*, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain • Cardiovascular: dizziness*, fainting, tachycardia, hypotension • Skin/mucosal: generalized hives, itching, or swelling of lips, face, throat *these can be subjective and overlap with anxiety or vasovagal syndrome Labs that can help assess for anaphylaxis • Tryptase, serum (red top tube) • C5b-9 terminal complement complex Level, serum (SC5B9) (lavender top EDTA tube) Emergency Supplies Management of anaphylaxis at a COVID-19 vaccination site • If anaphylaxis is suspected, take the following steps: • Rapidly assess airway, breathing, circulation, and mentation (mental activity).