End of Project Report to Oxfam – 2014-2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rotarians Against Malaria

ROTARIANS AGAINST MALARIA LONG LASTING INSECTICIDAL NET DISTRIBUTION REPORT MOROBE PROVINCE Bulolo, Finschafen, Huon Gulf, Kabwum, Lae, Menyamya, and Nawae Districts Carried Out In Conjunction With The Provincial And District Government Health Services And The Church Health Services Of Morobe Province With Support From Against Malaria Foundation and Global Fund 1 May to 31 August 2018 Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 3 Background ........................................................................................................................... 4 Schedule ............................................................................................................................... 6 Methodology .......................................................................................................................... 6 Results .................................................................................................................................10 Conclusions ..........................................................................................................................13 Acknowledgements ..............................................................................................................15 Appendix One – History Of LLIN Distribution In PNG ...........................................................15 Appendix Two – Malaria In Morobe Compared With Other Provinces ..................................20 -

2011 Annual Report

Buk bilong Pikinini Annual Report for 2011 Contents Contacts…………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 2 The Buk Bilong Pikinini Story………………………………………………………………………….... Page 3 Statement from the Founder……………………………………………………………………………. Page 5 Our Development Strategy………………………………………………………………………………. Page 8 Our Logic Framework………………………………………………………………………………………. Page 14 Operational Structure………………………………………………………………………………………. Page 15 Map of BbP’s work…………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 16 The Libraries……………………………………………………………………………………………………. Page 17 Port Moresby General Hospital……………………………………………………………… Page 18 Hohola………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Page 20 Lawes Road…………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 22 Lae………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 25 6 Mile……………………………………………………………………………………………………. Page 27 Goroka……………………………………………………………………………………………….… Page 29 Koki……………………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 31 University of PNG………………………………………………………………………………… Page 34 Our 5-year strategic plan………………………………………………………………………………… Page 36 Thank you to all our donors, staff and volunteers…………………………………………… Page 37 1 Contacts Buk bilong Pikinini Founder Executive Director Mrs Anne Sophie Hermann Mrs Ali Nott C/- PNG High Commission PO BOX 5791 39 – 41 Forster Crescent Boroko Yarralumla ACT 2600 Port Moresby Australia Papua New Guinea Phone: +61 2 6273 3322 Phone: +675 340 8827 Fax: +61 2 6273 3732 Fax: +675 325 5503 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] PNG Office Manager Early Childhood Development Co-ordinator Mrs -

CHAPTER 12 INFRASTRUCTURE and SERVICES PLAN (Sectoral)

The Project for the Study on Lae-Nadzab Urban Development Plan in Papua New Guinea CHAPTER 12 INFRASTRUCTURE AND SERVICES PLAN (Sectoral) Spatial and economic development master plans prepared in the previous Chapter 11 are the foundation of infrastructure and social service development projects. In this chapter, the Project target sector sub-projects are proposed based on the sector based current infrastructure and social service status studies illustrated in Chapter 6 of the Report. In particular, transportation sector, water supply sector, sanitation & sewage sector, waste management sector, storm water & drainage sector and social service sector (mainly education and healthcare) are discussed, and power supply sector and telecommunication sector possibilities are indicated. Each of these sub-projects is proposed in order to maximize positive impact to the regional economic development as well as spatial development in the Project Area. Current economic activities and market conditions in the region are taken into consideration with the economic development master plan in order to properly identify local needs of infrastructure and social services. The development of industry to improve economic activities in the region becomes the key to change such livelihood in Lae-Nadzab Area with stable job creation, and proposed infrastructure sub-projects will be so arranged to maximize the integration with economic development. 12.1 Land Transport 12.1.1 Travel Demand Forecasting Figure 12.1.1 shows the flowchart of the travel demand forecasting process of the Project Area. The travel analysis was based on the traditional four-step model. The data from the household survey, person trip survey, traffic count survey and roadside interview survey were the main inputs of the analysis. -

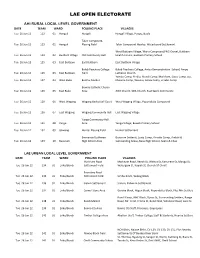

Lae Open Electorate

LAE OPEN ELECTORATE AHI RURAL LOCAL LEVEL GOVERNMENT DATE TEAM WARD POLLING PLACE VILLAGES Tue 26 Jun 12 122 01 Hengali Hengali Hengali Village, Poapu, Buala Talair Compound, Tue 26 Jun 12 123 01 Hengali Playing Field Talair Compound Nearby, Waterboard Settlement West Buitbam Village, Waria Compound,PNG Gravel, Buitbam Tue 26 Jun 12 124 02 Buitbam Village Old Community Hall Health Centre, Buitbam Primary School Tue 26 Jun 12 125 03 East Buitbam East Buitbam East Buitbam Village Balob Teachers College Balob Teachers College, Amba Demonstration School, Ampo Tue 26 Jun 12 126 03 East Buitbam Field Lutheran Church Yambo Comp, Pindiu, Mendi Comp, Markham, Siassi Comp, Sio, Tue 26 Jun 12 127 04 West Buko Bumbu Market Maiama Comp, Woseta, Amoa Comp, Zinabe Comp Bumbu Catholic Church Tue 26 Jun 12 128 05 East Buko Area AOG Church, SDA Church, East Sepik Community Tue 26 Jun 12 129 06 West Wagang Wagang Basketball Court West Wagang Village, Popondetta Compound Tue 26 Jun 12 130 07 East Wagang Wagang Community Hall East Wagang Village Yanga Community Hall Tue 26 Jun 12 131 08 Yanga Area Yanga Village, Bowali Primary School Tue 26 Jun 12 132 09 Gawang Hunter Playing Field Hunter Settlement Emmanuel Lutheran Busurum Settmnt, Lusip Comp, Arnotts Comp, Ambisi & Tue 26 Jun 12 133 10 Busurum High School Area Surrounding Areas, Busu High School, Seeto & Chan LAE URBAN LOCAL LEVEL GOVERNMENT DATE TEAM WARD POLLING PLACE VILLAGES Markham Road Markham Road, Beech St, Walnut St, Kamarere St, Mango St, Tue 26 Jun 12 134 01 Eriku/Bundi Settlement Field Watergum St, Kapiak St, Church Of Christ Boundary Road Tue 26 Jun 12 135 01 Eriku/Bundi Settlement Field Simbu Block, Wabag Block Tue 26 Jun 12 136 01 Eriku/Bundi Sialum Settlement Sialum, Kabwum Settlement Tue 26 Jun 12 137 01 Eriku/Bundi Corner Store Area Goroka Block, Hagen Block, Popondetta Block, Plus Mix Settlers Bundi Comp, NHC Block, Dysox St, Surrounding Settlers, Range Tue 26 Jun 12 138 01 Eriku/Bundi Bundi Market Road, Mr. -

Tanget No 72, December 2017

PNG TANGET News Leaflet of Mariannhill in Papua New Guinea No. 72, Vol. XIX/3 Mariannhill College Bomana December 2017 P.O. Box 54, Gordons, NCD _______________________________________________________ _________________________ resignation as Bishop of Lae. It Our two Fratres, Alois Gende must feel like waiting for a bus on and Wilfred Salhun , whose Dear friends of Mariannhill PNG! the beach. For Bishop Chris it may coming on home leave to PNG I sometimes even be heavier to bear mentioned in the Tanget of last This edition was meant to be than the pain of his arthritis. July, were received in Lae with the written in October but, as already Some more suffering may be going traditional festive evening in the in the past, time went faster than on in our small community, but “haus win” of Mariannhill House my typing. Sori tru! everyone is occupied in his pasto- at Eriku on the 23 rd of July. Their ral task, covering up with hard stories confirmed that the We are nearing Christmas and we, work and happy face the cleaning experience of their integration in Mariannhillers in PNG, are all in of his soul by bearing his part of our Zambian CMM community reasonably good shape, if this can the cross, following in this the has not only given them more also be said of Fr. Anthony example of our founder Abbot physical but also moral and Mulderink , who is just coming Francis, who envisaged his multi- spiritual weight and strength. out of the hospital in Lae, recove- ple sufferings exactly as such. -

1-Tok-Kaunselin Helpim Lain Service Provider Directory 2017

1-Tok Kaunselin Helpim Lain - 7150 8000 - Service Provider Directory A special thank you is extended to consultant Helen Haro who supported this work in partnership with ChildFund Papua New Guinea and to the 1-Tok Kaunselin Helpim Lain Counsellors who travelled to a range of provinces to carry out awareness with services across the referral network and collect new contact details. Thank you to all of the service providers across the network who work with the 1-Tok Kaunselin Helpim Lain to support survivors of gender based violence across Papua New Guinea. The 1-Tok Kaunselin Helpim Lain is a partnership between ChildFund Papua New Guinea, FSVAC (CIMC) and FHI 360, supported by the New Zealand Aid Programme, USAID, ChildFund New Zealand and ChildFund Australia. ChildFund Papua New Guinea ChildFund Papua New Guinea works in partnership with children and their communities to create lasting and meaningful change by supporting long-term community development and promoting child rights. ChildFund Papua New Guinea PO Box 671, Gordons NCD T: +675 323 2544 D: +675 7030 0297 W: www.childfund.org.au 1-Tok Kaunselin Helpim Lain - 7150 8000 - Service Provider Directory Contents Introduction to the 1-Tok Kaunselin Helpim Lain 3 The 1-Tok Kaunselin Helpim Lain Service Provider Directory 4 National Capital District 5 Bougainville 9 Central 12 Chimbu 13 Eastern Highlands 15 East New Britain 15 East Sepik 16 Enga 17 Gulf 18 Hela 18 Jiwaka 18 Madang 19 Manus 19 Milne Bay 20 Morobe 20 New Ireland 21 Oro 22 Sandaun 22 Southern Highlands 23 Western 23 Western -

Lae Lshed 140518

LOAD SHEDDING SCHEDULE LAE : EFFECTIVE DATE: Tuesday 15/05/18 . To be continued till Tuesday 29/05/18 Time Areas Aected NCI Laga Industry, Atlas steel, Mapai Transport, East/West Taraka, 09:00am - 09:30am, 1:00pm - 1:30pm Unitech Residential, Igam Barracks, Bumayong, Tent City, PTC & Back road area. 08:00am - 08:30am, Nawae/Bundi Camp, Bumbu Police Barracks, Lae Poly Tech, & Eriku 2:00pm - 2:30pm Shopping Centre. Lae Biscuit, Speedway, Kamkumung/Butibam Villages, China Town, 11:00am - 11:30am Nestle Factory, Hanta/Balop, Malahang Industrial area, Majestic Sea food & back road area. Dunlop Niugini Electrical, ESCO, ANZ Bank Main Land Hard ware, BSP 11:00am - 11:30am Market, Raumai Super Market, Main Market Shopping Centres, Bishop Brothers, Inter Oil Depot, Niugini Oil Company, ORICA, SP Brewery, Flour Mill, Amal Pack. Boroko Motors, Pelgens Freezer, COCA COLA Industry, PNG Ports Corpora- 10:00am - 10:30am, tion, Trukai Industries, Lae International Hospital, NGI Steel, Atlas Steel, 3:00pm - 3:30pm Zenag Freezer PNG Motors, K. K. Kingston, Papuan Compound residential area, BNBM home Centre, BNG Freezer. Fire Station, Golf Club & Eriku residential area, FRI, 7- 12 streets residen- 4:00pm - 4:30pm tial areas, Morobe Motel, Travellers Inn, Angao Nursing Quarters , Food Mart, Top Town area &Morobe Provincial Head Oces. PPL Workshop, Fredis Shop, Salamada/Javani residential areas, Bugandi 12:00pm - 12:30pm Secondary, 2-14 mile areas, Niugini Table Birds, Muya primary & Gaben- sis/Mare villages. Load shedding schedule Lae for Daewoo power plant maintenance. Schedule is subject to change as per generation and load demand without notice according to operational requirements only. -

Analytical Protocol to Estimate the Relative Importance Of

hydrology Communication Analytical Protocol to Estimate the Relative Importance of Environmental and Anthropogenic Factors in Influencing Runoff Quality in the Bumbu Watershed, Papua New Guinea Willie Doaemo 1,2 , Lawrence Wuest 3,*, Shaurya Bajaj 4, Wan Shafrina Wan Mohd Jaafar 5 and Midhun Mohan 4,6 1 Department of Civil Engineering, Papua New Guinea University of Technology, Lae 00411, Papua New Guinea; [email protected] 2 Morobe Development Foundation, Doyle Street, Trish Avenue-Eriku, Lae 00411, Papua New Guinea 3 United Nations Volunteer, Stanley, NB E6B 2K5, Canada 4 United Nations Volunteer, Morobe Development Foundation, Lae 00411, Papua New Guinea; [email protected] (S.B.); [email protected] (M.M.) 5 Earth Observation Centre, Institute of Climate Change, National University of Malaysia (UKM), Bangi 43600, Selangor, Malaysia; [email protected] 6 Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 9 September 2020; Accepted: 12 October 2020; Published: 14 October 2020 Abstract: The wellbeing, socio-economic viability and the associated health of the inhabitant species of any ecosystem are largely dependent on the quality of its water resources. In this regard, we developed a protocol to measure the potential impact of various environmental and anthropogenic factors on runoff quality at 22 water sampling sites across the Bumbu Watershed in Papua New Guinea. For this purpose, we utilized Digital Elevation Models and several GIS techniques for delineation of stream drainage patterns, classification of the watershed based on Land Use/Land Cover, spatial interpolation of rainfall patterns and computation of the corresponding factor runoff. -

PIMS 5261 R2R Project TE Final

United Nations Development Programme Global Environmental Facility FINAL (12/29/2020) Terminal Evaluation of the UNDP-Supported GEF-Financed Project R2R Strengthening the Management Effectiveness of the National System of Protected Areas GEF Project ID: 5510 UNDP PIMS ID: 5261 Country: Papua New Guinea Region: Asia and the Pacific GEF Focal Area: Multi-focal area: Biodiversity and Land Degradation (GEF-5) GEF Implementing Agency: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Project Executing Agencies: Conservation and Environment Protection Authority (CEPA) Woodlands Park Zoo (WPZ) Tenkile Conservation Alliance (TCA) Evaluation Time Frame: 1 September – 31 December 2020 Evaluation Team: Ms. Virginia Ravndal, International Consultant, Team Leader ([email protected]) Ms. Maureen Ewai, National Expert Consultant ([email protected]) Final TE Report PIMS 5261 Acknowledgments The evaluators thank all those who patiently took part in interviews and generously took time out of their busy days to share their perspectives and information crucial to the conduct of this evaluation. A haus tambaran of the Sepik culture, Drekikir District. Photo Credit: Madline Lahari (2020) i Final TE Report PIMS 5261 Contents 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Information Table ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Research Report

THE PAPUA NEW GUINEA RESEARCH REPORT Compiled and Edited by Department of Agriculture PNG University of Technology THE PAPUA NEW GUINEA UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH REPORT 2019 Compiled and Edited by Professor Shamsul Akanda Department of Agriculture RESEARCH REPORT 2019 PNG University of Technology CONTENTS Contents Page Contents i Foreword from the Research Committee Chairman ii Research Committee Terms of Reference and Membership iii Executive Summary iv Journal Publications from Academic Departments (2013-2019) vi Departmental Research Reports 1 Department of Agriculture 2 Department of Applied Physics 15 Department of Applied Sciences 17 Department of Architecture and Building 24 Department of Business Studies 26 Department of Civil Engineering 32 Department of Communication and Development Studies 40 Department of Electrical and Communication Engineering 59 Department of Forestry 74 Department of Mathematics and Computer Science 98 Department of Mechanical Engineering 101 Department of Mining Engineering 108 Department of Surveying and Lands Studies 109 Allocation of Research Fund 123 Allocation of Conference Fund 125 Abstracts – Unitech Seminar Series 126 RESEARCH REPORT 2019 i PNG University of Technology FOREWORD On behalf of the Research Committee of Unitech, I am delighted to present the 2019 Research Report of Papua New Guinea University of Technology. This is a compilation of the research activities of the fourteen academic departments and four research units of the university. I am very thankful to the Dean of Postgraduate School, Professor Shamsul Akanda, for compiling and editing the report. The Academic Board of Unitech has a Research Committee that receives applications for research funding from staff and students and allocates funds to them. -

Morobe Gold Project

Morobe Consolidated Goldfields Limited Morobe Gold Project Socio-Economic Impact Study Volume I Introduction, analysis of social and political risks, recommendations ► Volume II Area study and social mapping Volume III Working Papers March 2001 proof corrections 10 May 2001 document format remediated in Word 2007, 22 August 2010 Author With the assistance of John Burton Peter Bennett, MCG In 2001: Morobe Consolidated Goldfields Ngawae Mitio, MCG In 2010: Australian National University Lengeto Giam, MCG Wayang Kawa, MCG Susy Bonnell, Subada Consulting Jennifer Krimbu, MCG Boina Yaya, MCG CONTENTS Contents ............................................................................................................... i Abbreviations .................................................................................................... iv Chapter 1 Introduction and coverage of the report ....................................... 1 Topics summarily treated here .................................................................................................................... 1 Women‘s issues and village liaison work .................................................................................................. 1 Business development ................................................................................................................................ 1 National political linkages ......................................................................................................................... 1 Primary economy ...................................................................................................................................... -

Papua New Guinea: DREF Operation N° MDRPG004 GLIDE No

Papua New Guinea: DREF operation n° MDRPG004 GLIDE no. EP-2009-000185-PNG Cholera, dysentery and Update no. 1 influenza outbreaks 7 October 2009 The International Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) is a source of un-earmarked money created by the Federation in 1985 to ensure that immediate financial support is available for Red Cross and Red Crescent response to emergencies. The DREF is a vital part of the International Federation’s disaster response system and increases the ability of national societies to respond to disasters. Period covered by this update: 7 September to 7 October 2009. Summary: The Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) extension has been granted for CHF 359,058 to the Papua New Guinea Red Cross Society on 7 October 2009 to directly reach 300,000 people in 13 out of 20 provinces. Initially, CHF 43,878 (USD 41,339 or EUR 28,923) was allocated from DREF to support Papua New Guinea Red Cross Society (PNGRCS) in delivering immediate assistance to some 5,000 beneficiaries on 7 September 2009 in response to the outbreak. Unearmarked funds to repay DREF are encouraged. PNGRCS will continue to meet the needs of the people affected by extending the existing DREF and The Chairman of the Papua New Guinea Red implementing a strategy that includes hygiene Cross Society gaining insights at ground level information dissemination and community awareness assessment. Photo: International Federation to minimize or contain the spread of cholera, dysentery and influenza over a three-month timeframe. Recent developments include increasing the scope and the budget for this operation, which will now directly reach approximately 300,000 people, and indirectly reach 2.4 million people.