Lae Community Crime Survey, 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salamaua Falls

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89681-8 - The Battle for Wau: New Guinea’s Frontline 1942-1943 Phillip Bradley Excerpt More information CHAPTER 1 Salamaua Falls The town of Wau, at the head of the Bulolo Valley in what is now Papua New Guinea, had its foundation in gold. It was in the early 1920s that the first gold was found in the Bulolo Valley, with the first miner’s right issued in December 1923. As the goldfields developed, the coastal town of Salamaua became their key supply port. Salamaua lies some 50 kilometres to the northeast of Wau and almost 40 kilometres directly south of Lae across the Huon Gulf. The old town is on the isthmus of a peninsula that juts out into the Solomon Sea like an accusing finger, pointed to the northeast. On 21 October 1925 the first cargo boat, the MV Marsina, called at its port. As the news spread, more people came to Salamaua to head up into the mountains for the promise of riches at Wau. Both towns grew, though that growth would always be limited by the strenuous eight-day trek from the coast up to Wau. An air route was sorely needed. In 1927 a former Australian officer from the First World War, Cecil Levien, brought 250 native labourers to Lae and constructed a landing ground there. Ray Parer, who had been narrowly beaten by Sir Ross and Keith Smith as the first to fly from England to Australia, flew the first aeroplane, a De Havilland DH-4, from Rabaul to Lae. -

IEE: Papua New Guinea: Lae Port Development Project

Initial Environmental Examination October 2011 PNG: Lae Port Development Project – Additional Works Prepared by Independent Public Business Corporation for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 20 October 2011) Currency unit – kina (K) K1.00 = $0.454 $1.00 = K2.202 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BOD – biological oxygen demand CSC Construction Supervision Consultant CSD cutter suction dredger DO – dissolved oxygen DEC Department of Environment and Conservation DMP Drainage Management Plan DOE Director of Environment EIA – Environmental Impact Assessment EIA 2009 EIA approved in principle 2009 by DOE EIS Environmental Impact Statement EMP – environmental management plan ESA – Environmental and Safety Agent (Contractors) PMU – Environmental and Social Circle Division (in PMU) ESO – Environmental and Safety Officer (in PMU) ESS – Environmental and Safety Specialist (in CSC) GOP – Government of Papua New Guinea HIV – human immunodeficiency virus IEE – Initial Environmental Examination IES – International Environmental and Safety Specialist (in CSC) IPBC Independent Public Business Corporation IR Inception Report NES – National Environmental and Safety Specialist (in CSC) NGO – non-governmental organization LPDP – Lae Port Development Project MMP – Materials Management Plan MOE Minister of Environment MRA Mineral Resources Authority PMU – Project Implementation Unit (IPBC) PNGPCL PNG Ports Corporation Limited PPE – Personal Protective Equipment REA – rapid environmental assessment RP – Resettlement Plan Spoil Unusable peaty or clay dredged material SPS – ADB‟s Safeguard Policy Statement (2009) SR – sensitive receiver TA – Technical Assistance TOR – Terms of Reference TSP – total suspended particulate TSS – total suspended solids TOR – terms of reference TTMP – temporary Drainage management plan i WEIGHTS AND MEASURES dB(A) – Decibel (A-weighted) masl – Meters above sea level km – kilometer km/h – kilometer per hour m – meter m3 – cubic meter NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of Papua New Guinea ends on 31 December. -

Rotarians Against Malaria

ROTARIANS AGAINST MALARIA LONG LASTING INSECTICIDAL NET DISTRIBUTION REPORT MOROBE PROVINCE Bulolo, Finschafen, Huon Gulf, Kabwum, Lae, Menyamya, and Nawae Districts Carried Out In Conjunction With The Provincial And District Government Health Services And The Church Health Services Of Morobe Province With Support From Against Malaria Foundation and Global Fund 1 May to 31 August 2018 Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 3 Background ........................................................................................................................... 4 Schedule ............................................................................................................................... 6 Methodology .......................................................................................................................... 6 Results .................................................................................................................................10 Conclusions ..........................................................................................................................13 Acknowledgements ..............................................................................................................15 Appendix One – History Of LLIN Distribution In PNG ...........................................................15 Appendix Two – Malaria In Morobe Compared With Other Provinces ..................................20 -

Morobe Province

2021 QUARTER 1 PAYMENT 1 BATCH 1_Q1P1B121CENPPSV_MOROBE School CodeSchool Name Sector Code Province Name District Name Account No Bank Name Bb Name Enrollment Balance Pay 63001 ARIFIRAN COMMUNITY SCHOOL PRI MOROBE PROVINCE MARKHAM 1001282392 BSP Lae Market Service C252 9,273.60 63002 UMBANG PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI MOROBE PROVINCE NAWAE 1000352921 BSP Lae Top Town 201 7,396.80 63004 BOWALI PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI MOROBE PROVINCE LAE 1389854 WES Lae 797 29,329.60 63005 OGERANANG PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI MOROBE PROVINCE FINSCHAFEN 1000342403 BSP Lae Top Town 172 6,329.60 63006 BUMBUM PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI MOROBE PROVINCE MARKHAM 1000327931 BSP Lae Top Town 243 8,942.40 63007 BAYUNE PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI MOROBE PROVINCE BULOLO 1001388326 BSP Bulolo 349 12,843.20 63008 BUTIBAM PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI MOROBE PROVINCE LAE 2281540 WES Lae 744 27,379.20 63009 ERAP PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI MOROBE PROVINCE HUON 6000076603 WES Lae 735 27,048.00 63010 GABENSIS PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI MOROBE PROVINCE HUON 1000349314 BSP Lae Top Town 600 22,080.00 63011 GAGIDU PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI MOROBE PROVINCE FINSCHAFEN 1000386280 BSP Lae Top Town 463 17,038.40 63013 GUNAZAKING PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI MOROBE PROVINCE FINSCHAFEN 1000382053 BSP Lae Top Town 196 6,400.80 63014 HAKWANGE PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI MOROBE PROVINCE MENYAMYA 1000355804 BSP Lae Market Service C724 26,643.20 63015 HIAKWATA PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI MOROBE PROVINCE MENYAMYA 1000921345 BSP Bulolo 692 25,465.60 63016 HOBU PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI MOROBE PROVINCE LAE 1000056210 BSP Lae Commercial 429 15,787.20 63017 HOMPIRI PRIMARY SCHOOL PRI MOROBE PROVINCE -

Morobe & Madang Provinces

© Lonely Planet Publications 124 lonelyplanet.com MOROBE & MADANG PROVINCES •• History 125 HISTORY Volcanic eruptions at Rabaul in 1937 Ancient axe heads that have been found sug- prompted a decision to move the capital of Morobe & Madang gest people have been living in this part of New Guinea to Lae, but WWII intervened PNG for about 40,000 years. Simbai settle- and instead Lae, Salamaua and Rabaul be- ments date back 15,000 years. Bilbil and Yabob came major Japanese bases. The Japanese also Provinces people in Madang Province are famous for took Madang. their pots, which they’ve been trading with In early 1943 the Japanese, reeling from Morobe peoples and Highlanders for eons. defeats at Milne Bay and the Kokoda Track, If you have just rolled down the pot-holed roads of the Highlands on an arse-spanking The first European to spend any length attempted to take Port Moresby by attacking PMV, Morobe and Madang, with their beaches and bays, will be as welcome as a shot of of time on the PNG mainland was Russian towards Wau, marching over the mountains quinine after a bout of malaria. biologist Nicolai Miklouho-Maclay. He ar- from Salamaua. The Battle of Wau was fought rived at Astrolabe Bay, south of the present hand-to-hand after the ammunition ran out, Geographically speaking they are similar – both rise from pristine beaches and bays of site of Madang, in 1871 and stayed for 15 with villagers watching in much the same way that foreign researchers (with an advanced Papua New Guinea’s northern coast into a series of thickly forested hills, imposing mountain months before leaving to regain his health, which was badly affected by malaria. -

PACIFIC MANUSCRIPTS BUREAU Catalogue of South Seas

PACIFIC MANUSCRIPTS BUREAU Room 4201, Coombs Building College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200 Australia Telephone: (612) 6125 2521 Fax: (612) 6125 0198 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://rspas.anu.edu.au/pambu Catalogue of South Seas Photograph Collections Chronologically arranged, including provenance (photographer or collector), title of record group, location of materials and sources of information. Amended 18, 30 June, 26 Jul 2006, 7 Aug 2007, 11 Mar, 21 Apr, 21 May, 8 Jul, 7, 12 Aug 2008, 8, 20 Jan 2009, 23 Feb 2009, 19 & 26 Mar 2009, 23 Sep 2009, 19 Oct, 26, 30 Nov, 7 Dec 2009, 26 May 2010, 7 Jul 2010; 30 Mar, 15 Apr, 3, 28 May, 2 & 14 Jun 2011, 17 Jan 2012. Date Provenance Region Record Group & Location &/or Source Range Description 1848 J. W. Newland Tahiti Daguerreotypes of natives in Location unknown. Possibly in South America and the South the Historic Photograph Sea Islands, including Queen Collection at the University of Pomare and her subjects. Ref Sydney. (Willis, 1988, p.33; SMH, 14 Mar.1848. and Davies & Stanbury, 1985, p.11). 1857- Matthew New Guinea; Macarthur family albums, Original albums in the 1866, Fortescue Vanuatu; collected by Sir William possession of Mr Macarthur- 1879 Moresby Solomon Macarthur. Stanham. Microfilm copies, Islands Mitchell Library, PXA4358-1. 1858- Paul Fonbonne Vanuatu; New 334 glass negatives and some Mitchell Library, Orig. Neg. Set 1933 Caledonia, prints. 33. Noumea, Isle of Pines c.1850s- Presbyterian Vanuatu Photograph albums - Mitchell Library, ML 1890s Church of missions. -

2011 Annual Report

Buk bilong Pikinini Annual Report for 2011 Contents Contacts…………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 2 The Buk Bilong Pikinini Story………………………………………………………………………….... Page 3 Statement from the Founder……………………………………………………………………………. Page 5 Our Development Strategy………………………………………………………………………………. Page 8 Our Logic Framework………………………………………………………………………………………. Page 14 Operational Structure………………………………………………………………………………………. Page 15 Map of BbP’s work…………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 16 The Libraries……………………………………………………………………………………………………. Page 17 Port Moresby General Hospital……………………………………………………………… Page 18 Hohola………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Page 20 Lawes Road…………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 22 Lae………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 25 6 Mile……………………………………………………………………………………………………. Page 27 Goroka……………………………………………………………………………………………….… Page 29 Koki……………………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 31 University of PNG………………………………………………………………………………… Page 34 Our 5-year strategic plan………………………………………………………………………………… Page 36 Thank you to all our donors, staff and volunteers…………………………………………… Page 37 1 Contacts Buk bilong Pikinini Founder Executive Director Mrs Anne Sophie Hermann Mrs Ali Nott C/- PNG High Commission PO BOX 5791 39 – 41 Forster Crescent Boroko Yarralumla ACT 2600 Port Moresby Australia Papua New Guinea Phone: +61 2 6273 3322 Phone: +675 340 8827 Fax: +61 2 6273 3732 Fax: +675 325 5503 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] PNG Office Manager Early Childhood Development Co-ordinator Mrs -

CHAPTER 12 INFRASTRUCTURE and SERVICES PLAN (Sectoral)

The Project for the Study on Lae-Nadzab Urban Development Plan in Papua New Guinea CHAPTER 12 INFRASTRUCTURE AND SERVICES PLAN (Sectoral) Spatial and economic development master plans prepared in the previous Chapter 11 are the foundation of infrastructure and social service development projects. In this chapter, the Project target sector sub-projects are proposed based on the sector based current infrastructure and social service status studies illustrated in Chapter 6 of the Report. In particular, transportation sector, water supply sector, sanitation & sewage sector, waste management sector, storm water & drainage sector and social service sector (mainly education and healthcare) are discussed, and power supply sector and telecommunication sector possibilities are indicated. Each of these sub-projects is proposed in order to maximize positive impact to the regional economic development as well as spatial development in the Project Area. Current economic activities and market conditions in the region are taken into consideration with the economic development master plan in order to properly identify local needs of infrastructure and social services. The development of industry to improve economic activities in the region becomes the key to change such livelihood in Lae-Nadzab Area with stable job creation, and proposed infrastructure sub-projects will be so arranged to maximize the integration with economic development. 12.1 Land Transport 12.1.1 Travel Demand Forecasting Figure 12.1.1 shows the flowchart of the travel demand forecasting process of the Project Area. The travel analysis was based on the traditional four-step model. The data from the household survey, person trip survey, traffic count survey and roadside interview survey were the main inputs of the analysis. -

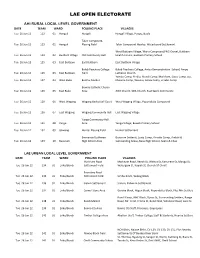

Lae Open Electorate

LAE OPEN ELECTORATE AHI RURAL LOCAL LEVEL GOVERNMENT DATE TEAM WARD POLLING PLACE VILLAGES Tue 26 Jun 12 122 01 Hengali Hengali Hengali Village, Poapu, Buala Talair Compound, Tue 26 Jun 12 123 01 Hengali Playing Field Talair Compound Nearby, Waterboard Settlement West Buitbam Village, Waria Compound,PNG Gravel, Buitbam Tue 26 Jun 12 124 02 Buitbam Village Old Community Hall Health Centre, Buitbam Primary School Tue 26 Jun 12 125 03 East Buitbam East Buitbam East Buitbam Village Balob Teachers College Balob Teachers College, Amba Demonstration School, Ampo Tue 26 Jun 12 126 03 East Buitbam Field Lutheran Church Yambo Comp, Pindiu, Mendi Comp, Markham, Siassi Comp, Sio, Tue 26 Jun 12 127 04 West Buko Bumbu Market Maiama Comp, Woseta, Amoa Comp, Zinabe Comp Bumbu Catholic Church Tue 26 Jun 12 128 05 East Buko Area AOG Church, SDA Church, East Sepik Community Tue 26 Jun 12 129 06 West Wagang Wagang Basketball Court West Wagang Village, Popondetta Compound Tue 26 Jun 12 130 07 East Wagang Wagang Community Hall East Wagang Village Yanga Community Hall Tue 26 Jun 12 131 08 Yanga Area Yanga Village, Bowali Primary School Tue 26 Jun 12 132 09 Gawang Hunter Playing Field Hunter Settlement Emmanuel Lutheran Busurum Settmnt, Lusip Comp, Arnotts Comp, Ambisi & Tue 26 Jun 12 133 10 Busurum High School Area Surrounding Areas, Busu High School, Seeto & Chan LAE URBAN LOCAL LEVEL GOVERNMENT DATE TEAM WARD POLLING PLACE VILLAGES Markham Road Markham Road, Beech St, Walnut St, Kamarere St, Mango St, Tue 26 Jun 12 134 01 Eriku/Bundi Settlement Field Watergum St, Kapiak St, Church Of Christ Boundary Road Tue 26 Jun 12 135 01 Eriku/Bundi Settlement Field Simbu Block, Wabag Block Tue 26 Jun 12 136 01 Eriku/Bundi Sialum Settlement Sialum, Kabwum Settlement Tue 26 Jun 12 137 01 Eriku/Bundi Corner Store Area Goroka Block, Hagen Block, Popondetta Block, Plus Mix Settlers Bundi Comp, NHC Block, Dysox St, Surrounding Settlers, Range Tue 26 Jun 12 138 01 Eriku/Bundi Bundi Market Road, Mr. -

Papua New Guinea: Lae Port Development Project

Completion Report Project Number: 40037 Loan Numbers: 2398, 2399, and 8237 Grant Number: 0102 Additional Financing Loan Numbers: 2803 and 2804 April 2017 Papua New Guinea: Lae Port Development Project This document is being disclosed to the public in accordance with ADB's Public Communications Policy 2011. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency unit – kina (K) At Appraisal At Additional At Project Completion Appraisal 31 July 2007 11 October 2011 16 December 2015 K1.00 = $0.3487 $0.4500 $0.3855 $1.00 = K2.810 K2.221 K2.600 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank EIRR – economic internal rate of return FIRR – financial internal rate of return IPBC – Independent Public Business Corporation JFPR – Japan Fund for Poverty Reduction KECC – Korean Engineering Consultants Corporation LIBOR – London interbank offered rate m – meter MPG – Morobe Provincial Government OFID – OPEC Fund for International Development OPEC – Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries PMU – project management unit PNG – Papua New Guinea PNGPCL – PNG Ports Corporation Limited PPP – public–private partnership PSC – project steering committee RHK – Royal Haskoning RRP – report and recommendation of the President Sida – Swedish Development Cooperation Agency SDR – special drawing right WACC – weighted average cost of capital NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of Papua New Guinea and its agencies ends on 31 December. (ii) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. Vice-President S. Groff, Operations 2 Director General X. Yao, Pacific Department (PARD) Country Director M. Minc, Papua New Guinea Resident Mission, PARD Team leader F. Ramos, Project Officer (Energy), PARD Team members J. Bego, Project Analyst, PARD D. Hill, Unit Head, Portfolio Management, PARD M. -

Tanget No 72, December 2017

PNG TANGET News Leaflet of Mariannhill in Papua New Guinea No. 72, Vol. XIX/3 Mariannhill College Bomana December 2017 P.O. Box 54, Gordons, NCD _______________________________________________________ _________________________ resignation as Bishop of Lae. It Our two Fratres, Alois Gende must feel like waiting for a bus on and Wilfred Salhun , whose Dear friends of Mariannhill PNG! the beach. For Bishop Chris it may coming on home leave to PNG I sometimes even be heavier to bear mentioned in the Tanget of last This edition was meant to be than the pain of his arthritis. July, were received in Lae with the written in October but, as already Some more suffering may be going traditional festive evening in the in the past, time went faster than on in our small community, but “haus win” of Mariannhill House my typing. Sori tru! everyone is occupied in his pasto- at Eriku on the 23 rd of July. Their ral task, covering up with hard stories confirmed that the We are nearing Christmas and we, work and happy face the cleaning experience of their integration in Mariannhillers in PNG, are all in of his soul by bearing his part of our Zambian CMM community reasonably good shape, if this can the cross, following in this the has not only given them more also be said of Fr. Anthony example of our founder Abbot physical but also moral and Mulderink , who is just coming Francis, who envisaged his multi- spiritual weight and strength. out of the hospital in Lae, recove- ple sufferings exactly as such. -

Morobe Province

DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION EDUCATION VACANCY GAZETTE 2021 Published by Authority Vol. 44, No. 01 WAIGANI, Friday 16th July 2021 _ MOROBE PROVINCE - 2 - T A B L E O F CO N T E N T S Pages SECTION A: INTRODUCTION/PREAMBLE DEFINITION……………………………………………………………… 4 OPERATIONAL TIMETABLE 1 OF 2021……………………………… 7 CHURCH CODE AND PHILOSOPHIES……………………….……...... 8 CODE FOR SUBJECT AREAS…………………………………….……. 13 POSTAL ADDRESS (Selection & Appointing Authorities) ……………. 14 SECTION B: ADVERTISED TEACHING VACANCIES PRIMARY SCHOOLS…………………………………………………….. 15 HIGH SCHOOLS ………………………………………………………….. 99 SECONDARY SCHOOLS…………………………...……………….…... 104 VOCATIONAL CENTRES.....….………................................................. 111 SECTION C: MISCELLANEOUS - ELIGIBILITY AWARDS ELIGIBILITY LISTS …………………………………………………… 115 - 3 - PAPUA NEW GUINEA TEACHING SERVICE VACANCIES (TEACHING SERVICE ACT NO. 12 OF 1988) DEFINITION Non-citizens outside PNG are not eligible to apply. In this preamble – WHO MUST APPLY “advertising authority” means the National Education Board (NEB) Concurrent Occupant – is a teacher who is substantive to “appointing authority” means the Provincial the level but is not the tenure holder of the position. The Education Board (PEB) and National teacher may have tenure on the same level elsewhere. Education Board (NEB) for national Unless they intend to return to their tenure position they must Institutions. apply for a new tenure position. “auxiliary member” means a person (non-citizen) who has been admitted to auxiliary membership of the Teaching Acting Occupant – The person who is acting on the position Service. higher than his or her substantive position. “member of the Teaching Service” or “member” means a national including a naturalized citizen who is a full member, a Anyone who is acting or a concurrent occupant must: provisional member, or an associate member of the Teaching apply upwards using their current eligibility.