Morobe Gold Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEIS Volume I

Morobe Consolidated Goldfields Limited Morobe Gold and Silver Project Socio-Economic Impact Study ► Volume I Introduction, analysis of social and political risks, recommendations Volume II Area study and social mapping Volume III Working Papers March 2001 proof corrections 9 May 2001 document format remediated in Word 2007, 22 August 2010 Author With the assistance of John Burton Peter Bennett, MCG In 2001: Morobe Consolidated Goldfields Ngawae Mitio, MCG In 2010: Australian National University Lengeto Giam, MCG Wayang Kawa, MCG Susy Bonnell, Subada Consulting Jennifer Krimbu, MCG Boina Yaya, MCG EXECUTIVE SUMMARY · This study characterises the stakeholder environment in the hinterland of the Morobe Gold and Silver Project. Its key objectives are to identify areas of risk in the inter- stakeholder relationships and to provide the means of ensuring equity in the distribution of mine-related benefits. · On present design, the project will be a small to medium sized operation, compared with the larger contemporary mining and petroleum operations in Papua New Guinea. Partly as a consideration of the project‘s size, this report deals only in passing with the project‘s macroeconomic contributions to Papua New Guinea, useful though they may be, instead looking much more closely at its effects within the District it is situated in, one of 89 in the country. · This emphasis is also helpful in focussing on the key social and political risks of the project at a time in the development of Papua New Guinea when contemporary political process has seen renewed efforts to de-centralise many of the planning and implementation functions of government to District level. -

Rotarians Against Malaria

ROTARIANS AGAINST MALARIA LONG LASTING INSECTICIDAL NET DISTRIBUTION REPORT MOROBE PROVINCE Bulolo, Finschafen, Huon Gulf, Kabwum, Lae, Menyamya, and Nawae Districts Carried Out In Conjunction With The Provincial And District Government Health Services And The Church Health Services Of Morobe Province With Support From Against Malaria Foundation and Global Fund 1 May to 31 August 2018 Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 3 Background ........................................................................................................................... 4 Schedule ............................................................................................................................... 6 Methodology .......................................................................................................................... 6 Results .................................................................................................................................10 Conclusions ..........................................................................................................................13 Acknowledgements ..............................................................................................................15 Appendix One – History Of LLIN Distribution In PNG ...........................................................15 Appendix Two – Malaria In Morobe Compared With Other Provinces ..................................20 -

RAPID ASSESSMENT of AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS and DIABETIC RETINOPATHY REPORT Papua New Guinea 2017

RAPID ASSESSMENT OF AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS AND DIABETIC RETINOPATHY REPORT Papua New Guinea 2017 RAPID ASSESSMENT OF AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS AND DIABETIC RETINOPATHY PAPUA NEW GUINEA, 2017 1 Acknowledgements The Rapid Assessment of Avoidable Blindness (RAAB) + Diabetic Retinopathy (DR) was a Brien Holden Vision Institute (the Institute) project, conducted in cooperation with the Institute’s partner in Papua New Guinea (PNG) – PNG Eye Care. We would like to sincerely thank the Fred Hollows Foundation, Australia for providing project funding, PNG Eye Care for managing the field work logistics, Fred Hollows New Zealand for providing expertise to the steering committee, Dr Hans Limburg and Dr Ana Cama for providing the RAAB training. We also wish to acknowledge the National Prevention of Blindness Committee in PNG and the following individuals for their tremendous contributions: Dr Jambi Garap – President of National Prevention of Blindness Committee PNG, Board President of PNG Eye Care Dr Simon Melengas – Chief Ophthalmologist PNG Dr Geoffrey Wabulembo - Paediatric ophthalmologist, University of PNG and CBM Mr Samuel Koim – General Manager, PNG Eye Care Dr Georgia Guldan – Professor of Public Health, Acting Head of Division of Public Health, School of Medical and Health Services, University of PNG Dr Apisai Kerek – Ophthalmologist, Port Moresby General Hospital Dr Robert Ko – Ophthalmologist, Port Moresby General Hospital Dr David Pahau – Ophthalmologist, Boram General Hospital Dr Waimbe Wahamu – Ophthalmologist, Mt Hagen Hospital Ms Theresa Gende -

Morobe Gold and Silver Project Socio-Economic Impact Study

Morobe Consolidated Goldfields Limited Morobe Gold and Silver Project Socio-Economic Impact Study Volume I Introduction, analysis of social and political risks, recommendations Volume II Area study and social mapping Volume III Working Papers March 2001 proof corrections 9 May 2001 document format remediated in Word 2007, 22 August 2010 Author With the assistance of John Burton Peter Bennett, MCG In 2001: Morobe Consolidated Goldfields Ngawae Mitio, MCG In 2010: Australian National University Lengeto Giam, MCG Wayang Kawa, MCG Susy Bonnell, Subada Consulting Jennifer Krimbu, MCG Boina Yaya, MCG EXECUTIVE SUMMARY · This study characterises the stakeholder environment in the hinterland of the Morobe Gold and Silver Project. Its key objectives are to identify areas of risk in the inter- stakeholder relationships and to provide the means of ensuring equity in the distribution of mine-related benefits. · On present design, the project will be a small to medium sized operation, compared with the larger contemporary mining and petroleum operations in Papua New Guinea. Partly as a consideration of the project’s size, this report deals only in passing with the project’s macroeconomic contributions to Papua New Guinea, useful though they may be, instead looking much more closely at its effects within the District it is situated in, one of 89 in the country. · This emphasis is also helpful in focussing on the key social and political risks of the project at a time in the development of Papua New Guinea when contemporary political process has seen renewed efforts to de-centralise many of the planning and implementation functions of government to District level. -

Financial Inclusion and Financial Capability

Financial Inclusion and Financial Capability in Morobe and Madang Provinces, Papua New Guinea Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized An initial report of the Papua New Guinea Public Disclosure Authorized National Financial Capability Survey Bank of Papua New Guinea Institute of National Affairs 9363_PNG FinancialCapacitySurvey_1601939_CVR.indd 1 11/19/15 8:17 AM Bank of Papua New Guinea Papua New Guinea Institute for National Affairs The World Bank Financial Inclusion and Financial Capability in Morobe and Madang Provinces Papua New Guinea An initial report of the Papua New Guinea National Financial Capability Survey This Project is financially supported by the Korean Poverty Reduction and Socio-Economic Development Trust Fund II 9363_PNG FinancialCapacitySurvey_1601939_CH00_FM.indd 1 11/18/15 10:15 AM Cataloguing-in-Publication Data ISBN 9980-77-182-8 National Library Service—Papua New Guinea First published: June 2015 Published by: Institute of National Affairs P.O. Box 1530 Port Moresby NCD Papua New Guinea Copyright: This report is a joint product of the project team composed of staff and consultants from Bank of Papua New Guinea, the Institute of National Affairs and The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this report are entirely those of the authors and should do not necessarily reflect the views of Board of the Bank of Papua New Guinea, the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent, or the Board of Institute of National Affairs. The Bank of Papua New Guinea, Institute of National Affairs, and The World Bank do not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. -

A Review of the Implementation of the OLPG &

ONSTITUTIONAL AND C LAW REFORM COMMISSION A Review of the Implementation of the OLPG & LLG: A Six Provinces Survey MONOGRAPH NO. 1 CONSTITUTIONAL AND LAW REFORM COMMISSION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA MONOGRAPH 1 REVIEW OF THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE OLPG & LLG ON SERVICE DELIVERY ARRANGEMENTS: A SIX PROVINCES SURVEY Edited by DR LAWRENCE KALINOE ii Published in Port Moresby by: Constitutional and Law Reform Commission Level 1, Bank South Pacific Building, Boroko National Capital District Website: www.clrc.gov.pg Telephone: (675) 325 2862 (675) 325 2840 Fax: (675) 325 3375 Email: [email protected] [email protected] The Constitutional and Law Reform Commission is a successor to the Law Reform Commission and the Constitutional Development Commission. It was established in 2005 pursuant to provisions of the Constitutional and Law Reform Commission Act (No. 24 of 2004) that was enacted on 24 th November, 2004 and proclaimed into force in March 2005. ISBN: 9980-9900-7-4 © 2009 Government of Papua New Guinea The text in this document (excluding the coat of arms) may be reproduced free of charge in any medium to the extent allowed under Copyright and Neighbouring Rights Act 2000. The material must be acknowledged as State copyright and the title of the document acknowledged. iv Foreword _________________ There has been concerns raised about the state of affairs in the system of decentralization that we now have under the current Organic Law on Provincial and Local-level Governments – essentially that under this current system, delivery of basic government provided services such as in health, education, transportation, communication, etc., have deteriorated and that the current system is not functioning well. -

2011 Annual Report

Buk bilong Pikinini Annual Report for 2011 Contents Contacts…………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 2 The Buk Bilong Pikinini Story………………………………………………………………………….... Page 3 Statement from the Founder……………………………………………………………………………. Page 5 Our Development Strategy………………………………………………………………………………. Page 8 Our Logic Framework………………………………………………………………………………………. Page 14 Operational Structure………………………………………………………………………………………. Page 15 Map of BbP’s work…………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 16 The Libraries……………………………………………………………………………………………………. Page 17 Port Moresby General Hospital……………………………………………………………… Page 18 Hohola………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Page 20 Lawes Road…………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 22 Lae………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 25 6 Mile……………………………………………………………………………………………………. Page 27 Goroka……………………………………………………………………………………………….… Page 29 Koki……………………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 31 University of PNG………………………………………………………………………………… Page 34 Our 5-year strategic plan………………………………………………………………………………… Page 36 Thank you to all our donors, staff and volunteers…………………………………………… Page 37 1 Contacts Buk bilong Pikinini Founder Executive Director Mrs Anne Sophie Hermann Mrs Ali Nott C/- PNG High Commission PO BOX 5791 39 – 41 Forster Crescent Boroko Yarralumla ACT 2600 Port Moresby Australia Papua New Guinea Phone: +61 2 6273 3322 Phone: +675 340 8827 Fax: +61 2 6273 3732 Fax: +675 325 5503 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] PNG Office Manager Early Childhood Development Co-ordinator Mrs -

CHAPTER 12 INFRASTRUCTURE and SERVICES PLAN (Sectoral)

The Project for the Study on Lae-Nadzab Urban Development Plan in Papua New Guinea CHAPTER 12 INFRASTRUCTURE AND SERVICES PLAN (Sectoral) Spatial and economic development master plans prepared in the previous Chapter 11 are the foundation of infrastructure and social service development projects. In this chapter, the Project target sector sub-projects are proposed based on the sector based current infrastructure and social service status studies illustrated in Chapter 6 of the Report. In particular, transportation sector, water supply sector, sanitation & sewage sector, waste management sector, storm water & drainage sector and social service sector (mainly education and healthcare) are discussed, and power supply sector and telecommunication sector possibilities are indicated. Each of these sub-projects is proposed in order to maximize positive impact to the regional economic development as well as spatial development in the Project Area. Current economic activities and market conditions in the region are taken into consideration with the economic development master plan in order to properly identify local needs of infrastructure and social services. The development of industry to improve economic activities in the region becomes the key to change such livelihood in Lae-Nadzab Area with stable job creation, and proposed infrastructure sub-projects will be so arranged to maximize the integration with economic development. 12.1 Land Transport 12.1.1 Travel Demand Forecasting Figure 12.1.1 shows the flowchart of the travel demand forecasting process of the Project Area. The travel analysis was based on the traditional four-step model. The data from the household survey, person trip survey, traffic count survey and roadside interview survey were the main inputs of the analysis. -

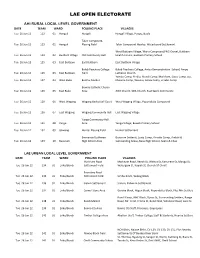

Lae Open Electorate

LAE OPEN ELECTORATE AHI RURAL LOCAL LEVEL GOVERNMENT DATE TEAM WARD POLLING PLACE VILLAGES Tue 26 Jun 12 122 01 Hengali Hengali Hengali Village, Poapu, Buala Talair Compound, Tue 26 Jun 12 123 01 Hengali Playing Field Talair Compound Nearby, Waterboard Settlement West Buitbam Village, Waria Compound,PNG Gravel, Buitbam Tue 26 Jun 12 124 02 Buitbam Village Old Community Hall Health Centre, Buitbam Primary School Tue 26 Jun 12 125 03 East Buitbam East Buitbam East Buitbam Village Balob Teachers College Balob Teachers College, Amba Demonstration School, Ampo Tue 26 Jun 12 126 03 East Buitbam Field Lutheran Church Yambo Comp, Pindiu, Mendi Comp, Markham, Siassi Comp, Sio, Tue 26 Jun 12 127 04 West Buko Bumbu Market Maiama Comp, Woseta, Amoa Comp, Zinabe Comp Bumbu Catholic Church Tue 26 Jun 12 128 05 East Buko Area AOG Church, SDA Church, East Sepik Community Tue 26 Jun 12 129 06 West Wagang Wagang Basketball Court West Wagang Village, Popondetta Compound Tue 26 Jun 12 130 07 East Wagang Wagang Community Hall East Wagang Village Yanga Community Hall Tue 26 Jun 12 131 08 Yanga Area Yanga Village, Bowali Primary School Tue 26 Jun 12 132 09 Gawang Hunter Playing Field Hunter Settlement Emmanuel Lutheran Busurum Settmnt, Lusip Comp, Arnotts Comp, Ambisi & Tue 26 Jun 12 133 10 Busurum High School Area Surrounding Areas, Busu High School, Seeto & Chan LAE URBAN LOCAL LEVEL GOVERNMENT DATE TEAM WARD POLLING PLACE VILLAGES Markham Road Markham Road, Beech St, Walnut St, Kamarere St, Mango St, Tue 26 Jun 12 134 01 Eriku/Bundi Settlement Field Watergum St, Kapiak St, Church Of Christ Boundary Road Tue 26 Jun 12 135 01 Eriku/Bundi Settlement Field Simbu Block, Wabag Block Tue 26 Jun 12 136 01 Eriku/Bundi Sialum Settlement Sialum, Kabwum Settlement Tue 26 Jun 12 137 01 Eriku/Bundi Corner Store Area Goroka Block, Hagen Block, Popondetta Block, Plus Mix Settlers Bundi Comp, NHC Block, Dysox St, Surrounding Settlers, Range Tue 26 Jun 12 138 01 Eriku/Bundi Bundi Market Road, Mr. -

Project Evaluation Report

Project Evaluation Report CS.0743 & CS.0820 Community Based Tribal Conflict Mitigation and Peace Building in Enga and Morobe Province, Papua New Guinea (COMBAT-COMIT) Phase I and II (December 2015 to November 2017) Funded by IOM Development Fund Final: 24 May 2019 Internal Evaluators: Reiko Matsuyama, Regional Project Development Officer & Sokleang Kim, Regional M&E Officer Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 3 1.1 Main Findings and Conclusions ..................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Recommendations ........................................................................................................................ 4 2. ACRONYMS ........................................................................................................... 6 3. BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................... 7 3.1 Context .......................................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Evaluation Purpose, Scope and Criteria ...................................................................................... 10 3.3 Evaluation Methodology ............................................................................................................. 12 3.4 Limitations .................................................................................................................................. -

Life Expectancy of Kokoda Track Authority Communities in Central Province, Papua New Guinea John Burton

34 Burton, Life expectancy of Kokoda Track communities Life expectancy of Kokoda Track Authority communities in Central Province, Papua New Guinea John Burton Abstract A cohort survival method is used to construct life tables for resident and non-resident families in Ward 18 of the Koiari Rural Local-Level Government. The life tables plausibly show that the rural-dwelling residents had a life expectancy of 49.9 years compared to 61.1 years for the Port Moresby-dwelling non-residents. The finding reveals a gap in life expectancy between rural and urban Papua New Guineans suggesting rural-dwellers are 30 years behind urban- dwellers in health status, the two figures matching life expectancy from the 1980 census (49.6 years) and as quoted by UNDP for PNG in 2010 (61.1 years). It backs the findings of general reviews that PNG’s rural health service is ‘impaired’ and ‘unable to fulfil basic functions’. Key words: Life expectancy, rural health. Introduction The Kokoda Initiative Social Mapping Project was part of a programme of technical assistance provided by the Australian government to the PNG Department of Environment and Conservation1 (DEC) under the first and second bilateral ‘Joint Understanding between PNG and Australia on the Kokoda Track and Owen Stanley Ranges’ agreements (Commonwealth of Australia & GoPNG, 2008, 2010). The objective of the project was to provide DEC and other Kokoda Initiative stakeholders with detailed profile of the communities making up the LLG wards of Kokoda Track Authority (KTA), an entity created in the late 1990s or early 2000s as a Special Purpose Authority under the Local-level Governments Administration 1997 (Filer, 2004, Table 1). -

Download 2.2 MB

Due Diligence Report Project Number: 41509-013 November 2016 PNG: Rural Primary Health Services Delivery Project (Loan 2785 and Grant 0259) Prepared by the Department of Health for the Asian Development Bank. This due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgements as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Papua New Guinea Rural Primary Health Services Delivery Project DUE DILIGENCE REPORT FOR ACQUISITION of the GARASA CHP SITE Morobe Province November, 2016 INDEX Executive Summary Project and Community Health Post Description Garasa Community Health Post Site - Description and Area Scope of Land Use/Purchase Socioeconomic Information Information Disclosure, Consultations and Participation Grievance Redress Mechanism Applicable Policies and Laws Agreements on Land Use Compensation and Benefits Budget and Sources of Funds Institutional Arrangements Implementation Schedule Monitoring and Reporting ANNEXURES (Available Upon Request) Annex One: Reports of Community Consultations Annex Two: Minutes of Landowner meeting Annex Three: Signed Customary Land Transfer Agreement Annex Four: Land survey of site Annex Five: Land Investigation Report Annex Six: Valuation Report Annex Seven: Certificate of Alienability Annex Eight: Deed of Release Annex Nine: Approved Layout Plan for Community Health Post The image on the cover of this Report depicts the area upon which the proposed Garasa CHP will be constructed.