Simon Lewis T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In and out of Africa She Was the Girl Who Lost It All – the Father, the Husband, the Farm and the Love of Her Life – but Won It Back by Writing About It

SCANDINAVIAN KAREN BLIXEN LEGENDS Bror and Karen Blixen as big game hunters in 1914. In and out of Africa She was the girl who lost it all – the father, the husband, the farm and the love of her life – but won it back by writing about it. KAREN huNtINg BLIXEN chose not to take her own life and against all odds she survived the syphilis she got from her husband – but died from undernourishment. Marianne Juhl tells the spectacular story of the foR A LIfE Danish author who became world famous for her novel Out of Africa. 2 SCANORAMA MARCH 2007 SCANORAMA MARCH 2007 3 n April 10, 1931, Karen Blixen sat down at Finch Hatton. Before long the two of them were embroiled in a the desk on her farm in the Ngong Hills in passionate affair. But Blixen was to lose Hatton, too. In 1931, his Kenya to write the most important letter little Gypsy Moth biplane crashed in flames in Kenya. Even if of her life. It was one week before her 46th there was much to suggest that the initial ardor in their relation- LEGENDS birthday and 17 years after she first came ship had cooled by this time, she nevertheless lost a close and to the country and the people whom she had grown to love with much-loved friend in the most dramatic of circumstances. oall her heart. Now, however, her coffee plantation was bankrupt She received the news of Hatton’s plane crash shortly before and had been sold. Karen had spent the past six months toiling learning she must leave the coffee farm in the Ngong Hills that she to gather in the final harvest and trying to secure the prospects had spent 17 years of her life running and fighting for – first with for her African helpers. -

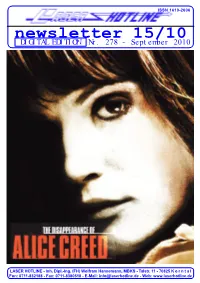

Newsletter 15/10 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 15/10 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 278 - September 2010 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 15/10 (Nr. 278) September 2010 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, auch jede Menge Filme auf dem liebe Filmfreunde! Fantasy Filmfest inspiziert. Diese sind Herzlich willkommen zum ersten jedoch in seinem Blog nicht enthalten, Newsletter nach unserer Sommer- sondern werden wie üblich zu einem pause. Es ist schon erstaunlich, wie späteren Zeitpunkt in einem separaten schnell so ein Urlaub vorbeigehen Artikel besprochen werden. Als ganz kann. Aber wie sollten wir es auch besonderes Bonbon werden wir in ei- merken? Denn die meiste Zeit ha- ner der nächsten Ausgaben ein exklu- ben wir im Kino verbracht. Unser sives Interview mit dem deutschstäm- Filmblogger Wolfram Hannemann migen Regisseur Daniel Stamm prä- hat es während dieser Zeit immer- sentieren, das unser Filmblogger wäh- hin auf satte 61 Filme gebracht! Da rend des Fantasy Filmfests anlässlich bleibt nicht viel Zeit für andere Ak- des Screenings von Stamms Film DER tivitäten, zumal einer der gesichte- LETZTE EXORZISMUS geführt ten Filme mit einer Lauflänge von 5 hat. ½ Stunden aufwartete. Während wir dieses Editorial schreiben ist er Sie sehen – es bleibt spannend! schon längst wieder dabei, Filmein- führungen für das bevorstehende Ihr Laser Hotline Team 70mm-Filmfestival der Karlsruher Schauburg zu schreiben. Am 1. Ok- tober geht’s los und hält uns und viele andere wieder für drei ganze Tage und Nächte auf Trab. -

Peetz: Erzählen Und Erzählungen in Blixen-Filmen

BERLINER BEITRÄGE ZUR SKANDINAVISTIK Titel/ »Erzählen und Erzählungen in Blixen-Filmen« title: Autor(in)/ Heike Peetz author: In: Heike Peetz, Stefanie von Schnurbein und Kirsten Wechsel (Hg.): Karen Blixen/Isak Dinesen/Tania Blixen. Eine internationale Erzählerin der Moderne. Berlin: Nordeuropa-Institut, 2008 ISBN: 3-932406-27-3 978-3-932406-27-0 Reihe/ Berliner Beiträge zur Skandinavistik, Bd. 12 series: ISSN: 0933-4009 Seiten/ 77-96 pages: © Copyright: Nordeuropa-Institut Berlin und Autoren © Copyright: Department for Northern European Studies Berlin and authors Diesen Band gibt es weiterhin zu kaufen. HEIKE PEETZ Erzählen und Erzählungen in Blixen-Filmen I Men muligheden for filmatiseringer af hendes arbejder interesserede hende al- tid, skønt hun selv var en sjælden gæst i biografen. Som sagt var hun helt naturligt interesseret i de indtægter, filmatiseringer kunne medføre, men alligevel var hun først og fremmest skeptisk overfor, hvad »filmmagere nu kunne finde på af fordrejninger«, som hun engang sagde.1 [Karen Blixen war immer an möglichen Verfilmungen ihrer Arbeiten interes- siert, auch wenn sie selbst selten ins Kino ging. Natürlich war sie an den Ein- nahmen aus den Verfilmungen interessiert, aber dennoch fragte sie sich vor al- lem skeptisch »auf was für Verdrehungen die Filmemacher kommen würden«, wie sie einmal sagte.] So äußert sich Keith Keller in seinem 1999 erschienenen Buch Karen Bli- xen og Filmen. Keller, der als Filmjournalist sowohl für dänische Tages- zeitungen als auch für das amerikanische Branchenblatt Variety schreibt, kannte die Autorin aus familiären Beziehungen. In seinem Buch stellt er diverse, häufig nicht verwirklichte Filmprojekte vor, die sich auf Blixen und ihre Werke beziehen. -

Study on out of Africa from the Perspective of Heterotopia

International Journal of Languages, Literature and Linguistics, Vol. 3, No. 4, December 2017 Study on Out of Africa from the Perspective of Heterotopia Yan Wang and Xiaolan Lei Abstract—Out of Africa gives us different imaginations of II RESEARCH STATUS spaces from the literal meaning, and many scholars have analyzed it from different perspectives. However, never has Karen Blixen has high visibility in European literary Foucault’s theory of heterotopia. This paper tries to give an circles. The British critic John Davenport spoke highly of analysis about the thinking spaces in this article combined with her,” In our time, few writers like her write less but refined the six features of Foucault's heterotopia, then shows us a [3]”. The Atlantic Monthly commended Karen “One of the different Africa and different ways of thinking. most elegant and unique artists of our time [3].” “The New York Times” commented that Karen was “a writer with Index Terms—Out of Africa, foucault, heterotopias. extraordinary imagination, smart and intelligent [3].” The literary critic, Jacques Henriksen, said that Karen is “the messenger of the distant journey, to tell people that there is I INTRODUCTION hope in the world [3].”For out of Africa, the British Victor·Hugo once said, “Africa is the most mysterious “Guardian” commented on it “depicts a passionate story, place in areas that people do not know [1].” In literature with the idyllic language to recall the lost homeland [3]”. field, this magic field also attracted many writers, and the Karen and Andersen are known as the Danish “literary famous Danish woman writer Isak Dinesen was one of treasures” and she is the winners of the Andersen Award them. -

Liebe Lesende

Vorwort 1 Liebe Lesende, wieder einmal wird es Winter und die Sonne scheint nicht mehr lange den lie- ben langen Tag. Aber da es auch abends und nachts noch schön ist, haben wir un- serem Heft diesmal einen dunklen Farbton gegeben, sodass Ihr es Euch damit auch im herbstlichen Park, der Bar oder zu Hause auf dem Sofa oder dem Bett gemütlich machen könnt, ohne dass Ihr unter dem grauen Himmel auffallt. Vielleicht wundert Ihr euch, wieder etwas von uns zu hören, doch obwohl un- sere Anschubfinanzierung durch die Ernst-Reuter-Gesellschaft mit dem letzten Heft endete, sind wir immer noch da. Der Dank dafür gilt den Instituten für Allgemeine und Vergleichende Literaturwissenschaften, Kunstgeschichte und Germanistik der Freien Universität Berlin und dem Bücherbasar e.V., die mit ihrer freundlichen finan- ziellen Unterstützung den Druck dieser Ausgabe ermöglicht haben. Dadurch könnt ihr auch in diesem Sommer einen Einblick in die Arbeit Eurer KommilitonInnen erhalten, und dafür geben wir Euch wieder eine Auswahl herausragender Texte aus dem weiten Feld der Geisteswissenschaften. Damit nicht genug – erstmals geben wir unserem Heft eine neue Ausrichtung und suchen unsere Beiträge jetzt auch bei den Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaf- ten. Die Antworten auf unseren call-for-notes aus diesem Fachbereich blieben lei- der noch recht vereinzelt, aber aller Anfang ist schwer. Wenn Ihr also dieses Heft in Händen haltet und Euch die eine oder andere eigene Hausarbeit in den Sinn kommt, oder aber wenn Ihr nach der Lektüre Lust bekommen habt, an der nächsten Ausgabe mitzuwirken, schreibt uns einfach eine Mail – wir freuen uns über jede Einsendung, die unser nächstes Heft bereichern und über jeden interessierten Helfer. -

History of the Karen Blixen Coffee Garden & Cottages

HISTORY OF THE KAREN BLIXEN COFFEE GARDEN & COTTAGES LTD. BY DR. BONNIE DUNBAR The Historic Swedo House was built around 1908 by the Swedo-African Coffee Company. Dr. Dunbar purchased the property and re- stored the old house in 1999. The Historic Swedo-House is a typical example of the architecture that existed during the pio- neering days of Kenya. It was built raised on stilts (still in place today with re-enforcement) which were to protect the building from water and termite damage. From “Letters From Africa The house was smaller than it is today, and consisted of 3 rooms and a veranda with a kitchen some yards away. It had corrugated iron walls lined with wood inside and a railed veranda and arched roof . In later years the walls outside “Swedo House” were “modernized” by removing the corrugated iron and replacing it with cement plastered over chicken wire. Inside the walls were paneled with Hessian which was painted with a thin layer of cement and finally white washed. The “prefabricated” slotted wood walls were imported from Europe sometime before the 1920s.The original colored lead windows remain intact today as they are shown with the original settlers. Anecdotal information from a neighbor (Mr. Russel) in Ka- ren is that his father built his house in 1908 and he knew that the Swedo house was two years older. (That house is no longer standing) It is told that United States President Theodore Roosevelt who was hosted by Sir Northrup McMillan hunted out of the Swedo House dur- ing his famous visit to Kenya in 1908 to collect specimens for the National Museums in Ameri- ca. -

Review of out of Africa

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research CUNY Graduate Center 2010 Review of Out of Africa Michael Adams City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_pubs/146 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Out of Africa (Blu-ray) (Universal, 4.27.2010) When people complain about the films undeservedly receiving the best-picture Oscar, Out of Africa is one of the frequent targets. As with The English Patient and Shakespeare in Love, Sydney Pollack’s film is the kind of lush, romantic drama that drives some, especially fanboys, nuts. Often dismissed a slick piece of Hollywood kitsch, Out of Africa succeeds in part because it’s a slick piece of Hollywood kitsch, with echoes of The Letter, Casablanca, The African Queen, and Lawrence of Arabia. One could easily imagine Katharine Hepburn or Ingrid Bergman playing Danish writer Karen Blixen, aka Isak Dinesen, but Meryl Streep is much better. Regardless of how you feel about the rest of Out of Africa, its main asset is Streep. I’m not sure how accurate her Danish accent is, but while some actors use accents as a crutch, even Streep herself at times (“A dingo ate my baby”), here it is simply one of several tools helping her to explore a complex character. Certainly Streep’s mannered, but when is she not? Her mannerisms are actually much subtler than usual. -

University of Copenhagen – ‘Carnival’ – Which Will Be the Subject of This Paper, Is Much Less Known

Flappers and Macabre Dandies Karen Blixen's "Carnival" in the Light of Søren Kierkegaard Bunch, Mads Published in: Scandinavica: An International Journal of Scandinavian Studies Publication date: 2012 Document version Early version, also known as pre-print Citation for published version (APA): Bunch, M. (2012). Flappers and Macabre Dandies: Karen Blixen's "Carnival" in the Light of Søren Kierkegaard. Scandinavica: An International Journal of Scandinavian Studies, 50(2), 74-108. Download date: 07. Apr. 2020 Scandinavica Vol 50 No 2 2011 Scandinavica Vol 50 No 2 2011 Flappers and Macabre Dandies: Introduction Karen Blixen’s ‘Carnival’ Two works, both influenced by Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, in the light of Søren Kierkegaard frame Karen Blixen’s production. Ehrengard – the late one – is by far the most famous. It was published a year after Karen Blixen’s death in 1963 and has had considerate attention from scholars, especially Mads Bunch in the past ten years (Sørensen, Møller and Kondrup). The early one University of Copenhagen – ‘Carnival’ – which will be the subject of this paper, is much less known. It is an early Gothic Tale, intended for the collection ‘Nine Tales by Nozdref’s Cook’ (Lasson 2008: 478), but it did not make Abstract the final cut (neither did ‘The Caryatids’) for what eventually became Despite almost making the cut for what later became Seven Seven Gothic Tales (1934) (Braad Thomsen 2011: 152). ‘Carnival’ was Gothic Tales (1934), Karen Blixen’s tale ‘Carnival’ has so far probably for the most part written in Africa 1926-27, but revised in had little attention by scholars. -

Kopi Fra DBC Webarkiv

Kopi fra DBC Webarkiv Kopi af: Lutherdom og teatralitet i Blichers "Præsten i Vejlbye" Dette materiale er lagret i henhold til aftale mellem DBC og udgiveren. www.dbc.dk e-mail: [email protected] 2014 Danske Studier Udgivet af Merete K. Jørgensen og Henrik Blicher under medvirken af David Svendsen-Tune Universitets-Jubilæets danske Samfund Universitets-Jubilæets danske Samfund nr. 586 Omslagsdesign: Jakob Brandt-Pedersen Printed in Denmark by Tarm Bogtryk A/S ISSN 0106-4525 ISBN 978-87-7674-879-1 Kommissionær: Syddansk Universitetsforlag, universitypress.dk Udgivet med støtte fra Det Frie Forskningsråd | Kultur og Kommunikation. Dette bind har været underkastet anonym fagfællebedømmelse. Alle årgange af Danske Studier fra 1904 til 2013 er nu frit tilgængelige på www.danskestudier.dk Bidrag til tidsskriftet sendes til: lektor Henrik Blicher seniorredaktør Institut for Nordiske Studier og Simon Boeck Skovgaard Sprogvidenskab Gammeldansk Ordbog Københavns Universitet Det Danske Sprog- og Njalsgade 120 Litteraturselskab 2300 København S Christians Brygge 1 1219 København K Redaktionen foretrækker at modtage bidrag elektronisk, og disse kan sendes til [email protected]. Bøger til redaktionen bedes sendt til Simon Boeck Skovgaard. Manuskripter (inkl. resume) skal være redaktionen i hænde inden 1. april 2015. Indhold Vibeke Sandersen, fhv. seniorforsker, dr.phil.: Ole Hansen Frølundes barndomserindringer og rejsedagbog fra Treårskrigen ........................................... 5 Lars Brink, professor, cand.mag., København og Jørgen Schack, seniorforsker, cand.mag., Dansk Sprognævn: Tale er sølv. Om begrebet syntaktisk ellipse ................. 45 Sune Gregersen, cand.mag.: Delt infinitiv i dansk ....................................... 76 Flemming Conrad, fhv. universitetslektor, dr.phil.: En diktat om dansk litteraturhistorie ....................... 88 Flemming Lundgren-Nielsen, docent, dr.phil, København: Ludvig Holbergs spejlkabinet. -

Finchatton Specializes

VANITY FAIR PROMOTION inchatton specializes in bespoke turn-key homes, the antithesis Andrew Dunn and Alex Michelin, co-founders of Finchatton, of “shouty luxury”, and introduce Twenty Grosvenor Square—their most ambitious to meet co-founders Andrew Dunn and project to date and home to the first stand-alone Four Seasons Alex Michelin is Private Residences in the world to understand why Mayfair Flair the emphasis is on “home” rather than Fproperty. The pair, friends who met at Charterhouse School, founded the international design and development company in 2001. The name emerged over a family Sunday lunch—a tribute to the charismatic big-game hunter and soulful lover of Karen Blixen in the film Out of Africa. Denys Finch Hatton was a renaissance man, a poet, pilot and safari adventurer, and it is this spirit of being one of a kind that gilds the Finchatton vision. Take their most ambitious project to date: Twenty Grosvenor Square, the first stand- alone Four Seasons Private Residences in the world. “It’s the pinnacle, the best address in Mayfair—a south-west facing property overlooking the grandest garden square in London,” says Michelin. “We’ve partnered with Four Seasons to create the best level of amenity in any building in London. It ticks all the boxes. It’s utterly unique, the culmination of our lives’ work to date, and it’s a responsibility we take seriously. We are cognisant of the history and want to develop and enhance this incredible classic property with a sensibility to make it one of the listed buildings of the future.” From its construction in the 1720s until the Second World War, Grosvenor Square, the largest garden square in Mayfair, was considered the most prestigious address in London. -

Karen Blixens Den Afrikanske Farm Og Moderne Boghistorie”

Abstract til speciale “Karen Blixens Den afrikanske Farm og moderne boghistorie” Karen Blixen or Isak Dinesen, as she is known inside the Anglo-American literature, is one of the most famous Danish authors in the world. Her second book from 1937, Den afrikanske Farm (Out of Africa) has been translated to more 20 different languages and is still her most popular book in Denmark. The book is, according to Blixen herself, a tale of the years she spent as a coffee farmer in the English colony, British East Africa (or Kenya) from 1914-31. Just like all the translation of her book, Blixen, her literature and Life has been the subject to many analyses. However, so far only one, with perspective of the discipline book history. Journalist Marianne Juhl wrote the article ”Om Den afrikanske Farm – tilblivelsen, udgivelsen og modtagelsen af Karen Blixens anden bog” in 1984, where she examined the history of Den afrikanske Farms publishing. She did, however, not use any tools or theories from book history. This I want to change. With the theory from Robert Darnton ground-breaking article ”What is the History of Books?” from 1982. In this paper, I wish develop Juhl’s work further by modifying the analytical model, Darntons proposed book historians to use, his Communications Circuit. The circuit runs through six general phases; the author, the publisher, the printers, the shippers, the booksellers and the readers. The circuit runs full with the reader, as authors often are readers themselves. I’ve chosen to focus on the author, the publisher and the -

Skibsdrengens Fortælling Sprog OG GENRE KAREN

SKOLETJENESTEMATERIALE KAREN bLIxENS LIV 3 HVEM ER JEG? 5 SKIbSdRENGENS fortæLLING 8 SpROG OG GENRE 10 KAREN bLIxENS AFRIKA 12 Hvem er jeg? Spørgsmålet om den menneskelige identitet, dvs. hvem man er, er et af de gennemgående temaer i Karen Blixens forfatterskab og er med til at gøre hendes fortællinger betydningsfulde og rele- vante i vores moderne verden. Flere af Karen Blixens fortællinger handler om den ofte svære overgang fra barn til voksen. Her formes vores identitet for alvor. Der er mange spørgsmål, der trænger sig på, samtidig med at man skal lære at klare sig selv. 7.-10. SKOLETJENESTEMATERIALE KLASSE FRA KAREN bLIxEN MuSEET < KAREN bLIxEN MuSEET SKOLETJENESTEMATERIALE Forsidefoto: Rie Nissen, 1935. / billedkunst.dk gerne 3 ”Frygtelig jeg have KAREN bLIxENS LIV ville …” været student Karen blixen Karen blixens baggrund Karen Blixen er en af Danmarks betydelig- Karen Blixens mor kom fra en velhavende søstre undervist hjemme på Rungstedlund ste digtere. Hun blev født på Rungstedlund borgerlig familie, der ernærede sig som af familie og privatlærerinder. Karen Blixen den 17. april 1885 og døde den 7. sep- handelsmænd, og som levede efter værdier var underlagt et stærkt kvindestyre, hvor tember 1962. Med undtagelse af de 17 år i som beskedenhed, flid og fromhed. Helt borgerlige værdier og dyder blev hyldet, Afrika levede Karen Blixen størstedelen af modsat farens familie, som havde aristokra- men det var hun konstant i opposition til. sit liv på Rungstedlund, som i dag huser tisk sindelag. Wilhelm Dinesens slægt hav- Karen Blixen Museet. de typisk levet som herremænd eller office- I Karen Blixens breve kan man læse, at hun Karen Blixen Museet rer.