AUC Philologica 1 2020 7390.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas Dinesen Junior Speech 12-10-2018 P.1/3 Your Majesty, You

Your Majesty, you’re Excellences, Ladies and Gentlemen I am, very honored, proud and thankful, to represent the family today and take part in the unveiling of the bust of our grandfather Thomas Dinesen, in connection with the commemoration of the centenary of the end of the Great war. Our grandfather Thomas Dinesen, was an exceptional man in many ways. As a soldier, sailor, hunter, resistance fighter, author, adventurer, public figure, brother, husband, and patriac. Today however, we are focusing on his role as cofounder and later Chairman of The Danish War Veterans of the Allies. And of course as a private soldier in the 42 Battalion, Royal Highlanders of Canada– The Black Watch, during the 1 st World War, where he was awarded the Victoria Cross “for valour”. Denmark was neutral during the war. As a consequence, the knowledge and understanding of the historic events between 1914 and 1918, is for Denmark that of a bystander. In the same way understanding the uniqueness, of the Victoria Cross and how it`s recipients are perceived in Great Britain and the Commonwealth, are somewhat lost on most Danes. Personally I have a different perspective, maybe quite naturally from being brought up with the stories of Grandfather`s deeds, both from himself and other family members, but also from having gone to School in England. I have a brother who lives and is married in England, I have been in the Danish army and am a member of the Special Forces club, based in London. So I have often been exposed, to how the British view this very special decoration rewarded, for courage in the face of the enemy. -

In and out of Africa She Was the Girl Who Lost It All – the Father, the Husband, the Farm and the Love of Her Life – but Won It Back by Writing About It

SCANDINAVIAN KAREN BLIXEN LEGENDS Bror and Karen Blixen as big game hunters in 1914. In and out of Africa She was the girl who lost it all – the father, the husband, the farm and the love of her life – but won it back by writing about it. KAREN huNtINg BLIXEN chose not to take her own life and against all odds she survived the syphilis she got from her husband – but died from undernourishment. Marianne Juhl tells the spectacular story of the foR A LIfE Danish author who became world famous for her novel Out of Africa. 2 SCANORAMA MARCH 2007 SCANORAMA MARCH 2007 3 n April 10, 1931, Karen Blixen sat down at Finch Hatton. Before long the two of them were embroiled in a the desk on her farm in the Ngong Hills in passionate affair. But Blixen was to lose Hatton, too. In 1931, his Kenya to write the most important letter little Gypsy Moth biplane crashed in flames in Kenya. Even if of her life. It was one week before her 46th there was much to suggest that the initial ardor in their relation- LEGENDS birthday and 17 years after she first came ship had cooled by this time, she nevertheless lost a close and to the country and the people whom she had grown to love with much-loved friend in the most dramatic of circumstances. oall her heart. Now, however, her coffee plantation was bankrupt She received the news of Hatton’s plane crash shortly before and had been sold. Karen had spent the past six months toiling learning she must leave the coffee farm in the Ngong Hills that she to gather in the final harvest and trying to secure the prospects had spent 17 years of her life running and fighting for – first with for her African helpers. -

Danish Victoria Cross Recipients

DANISH VICTORIA CROSS RECIPIENTS ED EMERING During World War I and World War II four Danes were occasions in the face of intense fire and managed awarded the Victoria Cross (Figure 1). Their names and to rescue six of the wounded. For his bravery and a brief biography of each is given below. leadership, he was the first Dane to receive the Victoria Cross. He continued serving during World War I and World War II and was eventually promoted to Brigadier. His Victoria Cross, along with his other medals, is on display at the Imperial War Museum in London. He is buried at the Garrison Cemetery in Copenhagen. Figure 1: The Victoria Cross. Brigadier Percy Hansen, VC, DSO and Bar, MC, (1890- 1951) (Figure 2) was born in Durban, South Africa. At age 24, he found himself serving as a Captain in the 6th Battalion of the Lincolnshire Regiment at Gallipoli, Turkey. On August 9, 1915, his Battalion was forced to retreat in the face of a deliberately set bush fire, leaving Figure 3: Corporal Jorgen Christian Jensen, VC. several wounded members on the field and in danger of being burned to death. Captain Hansen, along with Corporal Jorgen Christian Jensen, VC, (1891-1922) some volunteers re-entered the battlefield on several (Figure 4), who was born in Logstor, Denmark and who later became a British subject, received his Victoria Cross for actions at Noreuil, France during April 1917. On April 2nd, along with five comrades, he attacked a German barricade and machine gun position, resulting in the death of one German and the surrender of 45 others. -

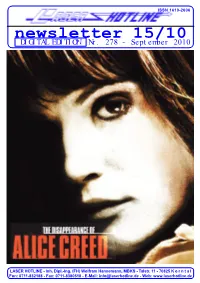

Newsletter 15/10 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 15/10 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 278 - September 2010 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 15/10 (Nr. 278) September 2010 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, auch jede Menge Filme auf dem liebe Filmfreunde! Fantasy Filmfest inspiziert. Diese sind Herzlich willkommen zum ersten jedoch in seinem Blog nicht enthalten, Newsletter nach unserer Sommer- sondern werden wie üblich zu einem pause. Es ist schon erstaunlich, wie späteren Zeitpunkt in einem separaten schnell so ein Urlaub vorbeigehen Artikel besprochen werden. Als ganz kann. Aber wie sollten wir es auch besonderes Bonbon werden wir in ei- merken? Denn die meiste Zeit ha- ner der nächsten Ausgaben ein exklu- ben wir im Kino verbracht. Unser sives Interview mit dem deutschstäm- Filmblogger Wolfram Hannemann migen Regisseur Daniel Stamm prä- hat es während dieser Zeit immer- sentieren, das unser Filmblogger wäh- hin auf satte 61 Filme gebracht! Da rend des Fantasy Filmfests anlässlich bleibt nicht viel Zeit für andere Ak- des Screenings von Stamms Film DER tivitäten, zumal einer der gesichte- LETZTE EXORZISMUS geführt ten Filme mit einer Lauflänge von 5 hat. ½ Stunden aufwartete. Während wir dieses Editorial schreiben ist er Sie sehen – es bleibt spannend! schon längst wieder dabei, Filmein- führungen für das bevorstehende Ihr Laser Hotline Team 70mm-Filmfestival der Karlsruher Schauburg zu schreiben. Am 1. Ok- tober geht’s los und hält uns und viele andere wieder für drei ganze Tage und Nächte auf Trab. -

Scan D Inavistica Viln Ensis 3

IS SCAN S D N 3 I N E A N V L I I S V T I A C Centre of Scandinavian Studies Faculty of Philology Vilnius University Ieva Steponavi)i*t+ Texts at Play Te Ludic Aspect of Karen Blixen’s Writings Vilnius University 2011 UDK / UDC 821.113.4(092) St-171 Te production of this book was funded by a grant (No MOK-23/2010) from the Research Council of Lithuania. Reviewed by Charlote Engberg, Associate Professor, Lic Phil (Roskilde University, Denmark) Jørgen Stender Clausen, Professor Emeritus (University of Pisa, Italy) Editorial board for the Scandinavistica Vilnensis series Dr Habil Jurij K. Kusmenko (Institute for Linguistic Studies under the Russian Academy of Sciences, Saint Petersburg / Humboldt University, Germany) Dr Phil Anatoly Liberman (University of Minnesota, USA) Dr Ērika Sausverde (Vilnius University) Dr Ieva Steponavičiūtė-Aleksiejūnienė (Vilnius University) Dr Aurelijus Vijūnas (National Kaohsiung Normal University, Taiwan) Approved for publishing at the meeting of the Council of the Faculty of Philology of Vilnius University (17 06 2011, record No 7) Designer Tomas Mrazauskas © Ieva Steponavičiūtė, 2011 © Vilnius University, 2011 ISSN 2029-2112 ISBN 978-9955-634-80-5 Vilnius University, Universiteto g. 3, LT-01513 Vilnius Tel. +370 5 268 7260 · www.leidykla.eu Centre of Scandinavian Studies · Faculty of Philology · Vilnius University Universiteto g. 5, LT-01513 Vilnius Tel. +370 5 268 7235 · www.skandinavistika.ff.vu.lt To my family Much is demanded of those who are to be really profcient at play. Courage and imagination, humor and intelligence, but in particular that blend of unselfshness, generosity, self-control and courtesy that is called gentilezza. -

Peetz: Erzählen Und Erzählungen in Blixen-Filmen

BERLINER BEITRÄGE ZUR SKANDINAVISTIK Titel/ »Erzählen und Erzählungen in Blixen-Filmen« title: Autor(in)/ Heike Peetz author: In: Heike Peetz, Stefanie von Schnurbein und Kirsten Wechsel (Hg.): Karen Blixen/Isak Dinesen/Tania Blixen. Eine internationale Erzählerin der Moderne. Berlin: Nordeuropa-Institut, 2008 ISBN: 3-932406-27-3 978-3-932406-27-0 Reihe/ Berliner Beiträge zur Skandinavistik, Bd. 12 series: ISSN: 0933-4009 Seiten/ 77-96 pages: © Copyright: Nordeuropa-Institut Berlin und Autoren © Copyright: Department for Northern European Studies Berlin and authors Diesen Band gibt es weiterhin zu kaufen. HEIKE PEETZ Erzählen und Erzählungen in Blixen-Filmen I Men muligheden for filmatiseringer af hendes arbejder interesserede hende al- tid, skønt hun selv var en sjælden gæst i biografen. Som sagt var hun helt naturligt interesseret i de indtægter, filmatiseringer kunne medføre, men alligevel var hun først og fremmest skeptisk overfor, hvad »filmmagere nu kunne finde på af fordrejninger«, som hun engang sagde.1 [Karen Blixen war immer an möglichen Verfilmungen ihrer Arbeiten interes- siert, auch wenn sie selbst selten ins Kino ging. Natürlich war sie an den Ein- nahmen aus den Verfilmungen interessiert, aber dennoch fragte sie sich vor al- lem skeptisch »auf was für Verdrehungen die Filmemacher kommen würden«, wie sie einmal sagte.] So äußert sich Keith Keller in seinem 1999 erschienenen Buch Karen Bli- xen og Filmen. Keller, der als Filmjournalist sowohl für dänische Tages- zeitungen als auch für das amerikanische Branchenblatt Variety schreibt, kannte die Autorin aus familiären Beziehungen. In seinem Buch stellt er diverse, häufig nicht verwirklichte Filmprojekte vor, die sich auf Blixen und ihre Werke beziehen. -

Study on out of Africa from the Perspective of Heterotopia

International Journal of Languages, Literature and Linguistics, Vol. 3, No. 4, December 2017 Study on Out of Africa from the Perspective of Heterotopia Yan Wang and Xiaolan Lei Abstract—Out of Africa gives us different imaginations of II RESEARCH STATUS spaces from the literal meaning, and many scholars have analyzed it from different perspectives. However, never has Karen Blixen has high visibility in European literary Foucault’s theory of heterotopia. This paper tries to give an circles. The British critic John Davenport spoke highly of analysis about the thinking spaces in this article combined with her,” In our time, few writers like her write less but refined the six features of Foucault's heterotopia, then shows us a [3]”. The Atlantic Monthly commended Karen “One of the different Africa and different ways of thinking. most elegant and unique artists of our time [3].” “The New York Times” commented that Karen was “a writer with Index Terms—Out of Africa, foucault, heterotopias. extraordinary imagination, smart and intelligent [3].” The literary critic, Jacques Henriksen, said that Karen is “the messenger of the distant journey, to tell people that there is I INTRODUCTION hope in the world [3].”For out of Africa, the British Victor·Hugo once said, “Africa is the most mysterious “Guardian” commented on it “depicts a passionate story, place in areas that people do not know [1].” In literature with the idyllic language to recall the lost homeland [3]”. field, this magic field also attracted many writers, and the Karen and Andersen are known as the Danish “literary famous Danish woman writer Isak Dinesen was one of treasures” and she is the winners of the Andersen Award them. -

Liebe Lesende

Vorwort 1 Liebe Lesende, wieder einmal wird es Winter und die Sonne scheint nicht mehr lange den lie- ben langen Tag. Aber da es auch abends und nachts noch schön ist, haben wir un- serem Heft diesmal einen dunklen Farbton gegeben, sodass Ihr es Euch damit auch im herbstlichen Park, der Bar oder zu Hause auf dem Sofa oder dem Bett gemütlich machen könnt, ohne dass Ihr unter dem grauen Himmel auffallt. Vielleicht wundert Ihr euch, wieder etwas von uns zu hören, doch obwohl un- sere Anschubfinanzierung durch die Ernst-Reuter-Gesellschaft mit dem letzten Heft endete, sind wir immer noch da. Der Dank dafür gilt den Instituten für Allgemeine und Vergleichende Literaturwissenschaften, Kunstgeschichte und Germanistik der Freien Universität Berlin und dem Bücherbasar e.V., die mit ihrer freundlichen finan- ziellen Unterstützung den Druck dieser Ausgabe ermöglicht haben. Dadurch könnt ihr auch in diesem Sommer einen Einblick in die Arbeit Eurer KommilitonInnen erhalten, und dafür geben wir Euch wieder eine Auswahl herausragender Texte aus dem weiten Feld der Geisteswissenschaften. Damit nicht genug – erstmals geben wir unserem Heft eine neue Ausrichtung und suchen unsere Beiträge jetzt auch bei den Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaf- ten. Die Antworten auf unseren call-for-notes aus diesem Fachbereich blieben lei- der noch recht vereinzelt, aber aller Anfang ist schwer. Wenn Ihr also dieses Heft in Händen haltet und Euch die eine oder andere eigene Hausarbeit in den Sinn kommt, oder aber wenn Ihr nach der Lektüre Lust bekommen habt, an der nächsten Ausgabe mitzuwirken, schreibt uns einfach eine Mail – wir freuen uns über jede Einsendung, die unser nächstes Heft bereichern und über jeden interessierten Helfer. -

History of the Karen Blixen Coffee Garden & Cottages

HISTORY OF THE KAREN BLIXEN COFFEE GARDEN & COTTAGES LTD. BY DR. BONNIE DUNBAR The Historic Swedo House was built around 1908 by the Swedo-African Coffee Company. Dr. Dunbar purchased the property and re- stored the old house in 1999. The Historic Swedo-House is a typical example of the architecture that existed during the pio- neering days of Kenya. It was built raised on stilts (still in place today with re-enforcement) which were to protect the building from water and termite damage. From “Letters From Africa The house was smaller than it is today, and consisted of 3 rooms and a veranda with a kitchen some yards away. It had corrugated iron walls lined with wood inside and a railed veranda and arched roof . In later years the walls outside “Swedo House” were “modernized” by removing the corrugated iron and replacing it with cement plastered over chicken wire. Inside the walls were paneled with Hessian which was painted with a thin layer of cement and finally white washed. The “prefabricated” slotted wood walls were imported from Europe sometime before the 1920s.The original colored lead windows remain intact today as they are shown with the original settlers. Anecdotal information from a neighbor (Mr. Russel) in Ka- ren is that his father built his house in 1908 and he knew that the Swedo house was two years older. (That house is no longer standing) It is told that United States President Theodore Roosevelt who was hosted by Sir Northrup McMillan hunted out of the Swedo House dur- ing his famous visit to Kenya in 1908 to collect specimens for the National Museums in Ameri- ca. -

Min Karen Blixen-Samling Og Et Praktisk Problem

Min Karen Blixen-samling og et praktisk problem Af K.F.Plesner Egentlig totalsamler af nogen enkelt forfatter har jeg aldrig været. Ikke engang af Baggesen. Sa skulle det snarere være af Johannes Smith, fordi vi for en menneskealder siden blev enige om for alle tilfældes skyld at udstationere et eksemplar af hvad vi skrev hos hinanden. Derimod har jeg af ikke så få forfattere nogenlunde fuld stændige rækker af originaludgaver — og, som jeg har sagt før: original er enhver udgave som bringer en ny, ændret eller øget text, fra senere optryk kan man roligt se bort, medmindre de skulle rumme et videnskabeligt noteapparat, som jo i så fald er originalt. En totalsamler af Karen Blixen måtte vel til at begynde med sla fast, at hun hører til en skrivende familie. Udgangspunktet måtte da blive hendes bedstefar A. W. Dinesens sjældne lille bog Abd-el-Kader, 1840, om krigen i Algier, hvori han deltog som frivillig. Dernæst hendes far Wilhelm Dinesen, af hvem man foruden de to samlinger Jagtbreve, 1889, og Nye Jagt breve, 1892, helst i de kønne, grønne komponerede shirtings bind, ikke blot skulle have bogen om kampen om Dybbøl, Fra ottende Brigade, 1889, og om hans deltagelse i den fransk tyske krig, Paris under Gommunen, 1872, men også de to udsnit fra Tilskueren 1887 om hans Ophold i De forenede Stater. Af hendes bror Thomas Dinesen er der både hans skildringer fra første verdenskrig No Man's Land, 1928, og hans egne uhyggelige og fantastiske fortællinger Syrenbusken, 1966 213 K. F. PLESNER 1952. Og endelig søsteren Ellen Dahl, der bl.a. -

Review of out of Africa

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research CUNY Graduate Center 2010 Review of Out of Africa Michael Adams City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_pubs/146 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Out of Africa (Blu-ray) (Universal, 4.27.2010) When people complain about the films undeservedly receiving the best-picture Oscar, Out of Africa is one of the frequent targets. As with The English Patient and Shakespeare in Love, Sydney Pollack’s film is the kind of lush, romantic drama that drives some, especially fanboys, nuts. Often dismissed a slick piece of Hollywood kitsch, Out of Africa succeeds in part because it’s a slick piece of Hollywood kitsch, with echoes of The Letter, Casablanca, The African Queen, and Lawrence of Arabia. One could easily imagine Katharine Hepburn or Ingrid Bergman playing Danish writer Karen Blixen, aka Isak Dinesen, but Meryl Streep is much better. Regardless of how you feel about the rest of Out of Africa, its main asset is Streep. I’m not sure how accurate her Danish accent is, but while some actors use accents as a crutch, even Streep herself at times (“A dingo ate my baby”), here it is simply one of several tools helping her to explore a complex character. Certainly Streep’s mannered, but when is she not? Her mannerisms are actually much subtler than usual. -

Wechsel: Wa(H)Re Identität

BERLINER BEITRÄGE ZUR SKANDINAVISTIK Titel/ »Wa(h)re Identität. Karen Blixens/Isak Dinesens Autorschaft im title: Zeichen der Kulturindustrie« Autor(in)/ Kirsten Wechsel author: In: Heike Peetz, Stefanie von Schnurbein und Kirsten Wechsel (Hg.): Karen Blixen/Isak Dinesen/Tania Blixen. Eine internationale Erzählerin der Moderne. Berlin: Nordeuropa-Institut, 2008 ISBN: 3-932406-27-3 978-3-932406-27-0 Reihe/ Berliner Beiträge zur Skandinavistik, Bd. 12 series: ISSN: 0933-4009 Seiten/ 151-170 pages: © Copyright: Nordeuropa-Institut Berlin und Autoren © Copyright: Department for Northern European Studies Berlin and authors Diesen Band gibt es weiterhin zu kaufen. KIRSTEN WECHSEL Wa(h)re Identität. Karen Blixens/Isak Dinesens Autorschaft im Zeichen der Kulturindustrie1 Die dänische Schriftstellerin Karen Blixen (1885–1962) – ihrem angelsäch- sischen Publikum unter dem Pseudonym Isak Dinesen bekannt – war immer wieder Gegenstand sowohl populärer Biographik als auch biogra- phisch gefärbter Literaturwissenschaft. In seiner ›queeren‹ Blixen-Lek- türe stellt der dänische Literaturwissenschaftler Dag Heede das immense biographische Interesse an Blixen in einen Zusammenhang mit ihrem ›posthumanen‹ Weltbild. In ihren Texten gäbe es, so lautet Heedes These, weder ›Menschen‹ noch ›Männer‹ oder ›Frauen‹, vielmehr dekonstruier- ten sie die Grundvorstellungen der modernen westlichen Kultur und ver- drängten das Subjekt aus dem Zentrum. Dies provoziere einen biographi- schen Diskurs, der das Menschliche hinter den so bedrohlich menschen- leeren Texten aufzuspüren