Characterization of Body Knotting Behavior in Hagfish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acid-Base Regulation in the Atlantic Hagfish Myxine Glutinosa

/. exp. Biol. 161, 201-215 (1991) 201 Printed in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists Limited 1991 ACID-BASE REGULATION IN THE ATLANTIC HAGFISH MYXINE GLUTINOSA BY D. G. McDONALD*, V. CAVDEK*, L. CALVERT* AND C. L. MLLLIGANf Huntsman Marine Science Centre, St Andrews, New Brunswick, Canada Accepted 10 July 1991 Summary Blood acid-base status and net transfers of acidic equivalents to the external environment were studied in hagfish, Myxine glutinosa, infused with ammonium sulphate (4mequivkg~1 NH4+) or with sulphuric acid (Smequivkg"1 H+). Hagfish extracellular fluids (ECF) play a greater role in acid-base regulation than in teleosts. This is because hagfish have a much larger blood volume relative to teleosts, despite a relatively low blood buffering capacity. Consequently, infusion of ammonium sulphate produced only half of the acidosis produced in marine teleosts in comparable studies, and hagfish readily tolerated a threefold greater direct H+ load. Furthermore, the H+ load was largely retained and buffered in the extracellular space. Despite smaller acid-base disturbances, rates of net H+ excretion to the external environment were, nonetheless, comparable to those of marine teleosts, and net acid excretion persisted until blood acid-base disturb- ances were corrected. We conclude that the gills of the hagfish are at least as competent for acid-base regulation as those of marine teleosts. The nature of the H+ excretion mechanism is discussed. Introduction + + In 1984, Evans found evidence for Na /H and C1~/HCO3~ exchanges in the primitive osmoconforming hagfish Myxine glutinosa L., and was the first to suggest that acid-base regulation by the gills preceded osmoregulation in the evolution of the vertebrates. -

Brains of Primitive Chordates 439

Brains of Primitive Chordates 439 Brains of Primitive Chordates J C Glover, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway although providing a more direct link to the evolu- B Fritzsch, Creighton University, Omaha, NE, USA tionary clock, is nevertheless hampered by differing ã 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. rates of evolution, both among species and among genes, and a still largely deficient fossil record. Until recently, it was widely accepted, both on morpholog- ical and molecular grounds, that cephalochordates Introduction and craniates were sister taxons, with urochordates Craniates (which include the sister taxa vertebrata being more distant craniate relatives and with hemi- and hyperotreti, or hagfishes) represent the most chordates being more closely related to echinoderms complex organisms in the chordate phylum, particu- (Figure 1(a)). The molecular data only weakly sup- larly with respect to the organization and function of ported a coherent chordate taxon, however, indicat- the central nervous system. How brain complexity ing that apparent morphological similarities among has arisen during evolution is one of the most chordates are imposed on deep divisions among the fascinating questions facing modern science, and it extant deuterostome taxa. Recent analysis of a sub- speaks directly to the more philosophical question stantially larger number of genes has reversed the of what makes us human. Considerable interest has positions of cephalochordates and urochordates, pro- therefore been directed toward understanding the moting the latter to the most closely related craniate genetic and developmental underpinnings of nervous relatives (Figure 1(b)). system organization in our more ‘primitive’ chordate relatives, in the search for the origins of the vertebrate Comparative Appearance of Brains, brain in a common chordate ancestor. -

St. Kitts Final Report

ReefFix: An Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) Ecosystem Services Valuation and Capacity Building Project for the Caribbean ST. KITTS AND NEVIS FIRST DRAFT REPORT JUNE 2013 PREPARED BY PATRICK I. WILLIAMS CONSULTANT CLEVERLY HILL SANDY POINT ST. KITTS PHONE: 1 (869) 765-3988 E-MAIL: [email protected] 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. Table of Contents 3 List of Figures 6 List of Tables 6 Glossary of Terms 7 Acronyms 10 Executive Summary 12 Part 1: Situational analysis 15 1.1 Introduction 15 1.2 Physical attributes 16 1.2.1 Location 16 1.2.2 Area 16 1.2.3 Physical landscape 16 1.2.4 Coastal zone management 17 1.2.5 Vulnerability of coastal transportation system 19 1.2.6 Climate 19 1.3 Socio-economic context 20 1.3.1 Population 20 1.3.2 General economy 20 1.3.3 Poverty 22 1.4 Policy frameworks of relevance to marine resource protection and management in St. Kitts and Nevis 23 1.4.1 National Environmental Action Plan (NEAP) 23 1.4.2 National Physical Development Plan (2006) 23 1.4.3 National Environmental Management Strategy (NEMS) 23 1.4.4 National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NABSAP) 26 1.4.5 Medium Term Economic Strategy Paper (MTESP) 26 1.5 Legislative instruments of relevance to marine protection and management in St. Kitts and Nevis 27 1.5.1 Development Control and Planning Act (DCPA), 2000 27 1.5.2 National Conservation and Environmental Protection Act (NCEPA), 1987 27 1.5.3 Public Health Act (1969) 28 1.5.4 Solid Waste Management Corporation Act (1996) 29 1.5.5 Water Courses and Water Works Ordinance (Cap. -

Caribbean Wildlife Undersea 2017

Caribbean Wildlife Undersea life This document is a compilation of wildlife pictures from The Caribbean, taken from holidays and cruise visits. Species identification can be frustratingly difficult and our conclusions must be checked via whatever other resources are available. We hope this publication may help others having similar problems. While every effort has been taken to ensure the accuracy of the information in this document, the authors cannot be held re- sponsible for any errors. Copyright © John and Diana Manning, 2017 1 Angelfishes (Pomacanthidae) Corals (Cnidaria, Anthozoa) French angelfish 7 Bipinnate sea plume 19 (Pomacanthus pardu) (Antillogorgia bipinnata) Grey angelfish 8 Black sea rod 20 (Pomacanthus arcuatus) (Plexaura homomalla) Queen angelfish 8 Blade fire coral 20 (Holacanthus ciliaris) (Millepora complanata) Rock beauty 9 Branching fire coral 21 (Holacanthus tricolor) (Millepora alcicornis) Townsend angelfish 9 Bristle Coral 21 (Hybrid) (Galaxea fascicularis) Elkhorn coral 22 Barracudas (Sphyraenidae) (Acropora palmata) Great barracuda 10 Finger coral 22 (Sphyraena barracuda) (Porites porites) Fire coral 23 Basslets (Grammatidae) (Millepora dichotoma) Fairy basslet 10 Great star coral 23 (Gramma loreto) (Montastraea cavernosa) Grooved brain coral 24 Bonnetmouths (Inermiidae) (Diploria labyrinthiformis) Boga( Inermia Vittata) 11 Massive starlet coral 24 (Siderastrea siderea) Bigeyes (Priacanthidae) Pillar coral 25 Glasseye snapper 11 (Dendrogyra cylindrus) (Heteropriacanthus cruentatus) Porous sea rod 25 (Pseudoplexaura -

Lamprey, Hagfish

Agnatha - Lamprey, Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Super Class: Agnatha Hagfish Agnatha are jawless fish. Lampreys and hagfish are in this class. Members of the agnatha class are probably the earliest vertebrates. Scientists have found fossils of agnathan species from the late Cambrian Period that occurred 500 million years ago. Members of this class of fish don't have paired fins or a stomach. Adults and larvae have a notochord. A notochord is a flexible rod-like cord of cells that provides the main support for the body of an organism during its embryonic stage. A notochord is found in all chordates. Most agnathans have a skeleton made of cartilage and seven or more paired gill pockets. They have a light sensitive pineal eye. A pineal eye is a third eye in front of the pineal gland. Fertilization of eggs takes place outside the body. The lamprey looks like an eel, but it has a jawless sucking mouth that it attaches to a fish. It is a parasite and sucks tissue and fluids out of the fish it is attached to. The lamprey's mouth has a ring of cartilage that supports it and rows of horny teeth that it uses to latch on to a fish. Lampreys are found in temperate rivers and coastal seas and can range in size from 5 to 40 inches. Lampreys begin their lives as freshwater larvae. In the larval stage, lamprey usually are found on muddy river and lake bottoms where they filter feed on microorganisms. The larval stage can last as long as seven years! At the end of the larval state, the lamprey changes into an eel- like creature that swims and usually attaches itself to a fish. -

A Review of Blue Crab Predators Status: TAES San Antonio Phone: 830-214-5878 Note: E-Mail: [email protected]

********************************************************************* ********************************************************************* Document-ID: 2225347 Patron: Note: NOTICE: ********************************************************************* ********************************************************************* Pages: 16 Printed: 02-22-12 11:45:34 Sender: Ariel/Windows Journal Title: proceedings of the blue crab 2/22/2012 8:35 AM , mortality symposium (ult state marine fisheries (Please update within 24 hours) commission publication) Ceil! #: SH380.45. L8 858 1999 Volume: Issue: 90 Month/Year: Pages: Nof Wanted 08/19/2012 Da~e: l' Article Author: Guillory, V and M Elliot Article Title: A review of blue crab predators Status: TAES San Antonio Phone: 830-214-5878 Note: E-mail: [email protected] Name: Bandel, Micaela T AES San Antonio 2632 Broadway, Suite 301 South San Antonio, TX 78215 I '' I i' Proceedings ofthe Blue Crab Symposium 69-83 n of d A Review of Blue Crab Predators \n. I ~s VINCENT GUILLORY AND MEGAN ELLIOT B- Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, P.O. Box 189, Bourg, Lou,,fana 70343 Abstract. - The diverse life history stages, abundance, and wide distributio> over a variety of habitats are attributes that expose blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus Rathbun) to nuinerous predators. An extensive literature search was undertaken on food habits of marine and estuarin,· invertebrate, and vertebrate species to identify predators of blue crab zoea, megalopae, and juveni k/adults. Ninety three species, which included invertebrates, fish, reptiles, birds, and mammals, were documented to prey upon blue crabs. An additional l l 9 sp~cies had other crab species or brachyur:m remains in their stomach contents. More fish species were identified as blue crab predators than any other taxonomic group (67), and 60 fish species were documented to prey upon unidentified crabs and/or brachyurans. -

Evaluation of O2 Uptake in Pacific Hagfish Refutes a Major Respiratory Role for the Skin Alexander M

© 2016. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2016) 219, 2814-2818 doi:10.1242/jeb.141598 SHORT COMMUNICATION It’s all in the gills: evaluation of O2 uptake in Pacific hagfish refutes a major respiratory role for the skin Alexander M. Clifford1,2,*, Alex M. Zimmer2,3, Chris M. Wood2,3 and Greg G. Goss1,2 ABSTRACT hagfishes, citing the impracticality for O2 exchange across the – Hagfish skin has been reported as an important site for ammonia 70 100 µm epidermal layer, perfusion of capillaries with arterial excretion and as the major site of systemic oxygen acquisition. blood of high PO2 and the impact of skin boundary layers on diffusion. However, whether cutaneous O2 uptake is the dominant route of uptake remains under debate; all evidence supporting this Here, we used custom-designed respirometry chambers to isolate hypothesis has been derived using indirect measurements. Here, anterior (branchial+cutaneous) and posterior (cutaneous) regions of we used partitioned chambers and direct measurements of oxygen Pacific hagfish [Eptatretus stoutii (Lockington 1878)] to partition whole-animal Ṁ and ammonia excretion (J ). Exercise consumption and ammonia excretion to quantify cutaneous and O2 ̇ Amm branchial exchanges in Pacific hagfish (Eptatretus stoutii) at rest and typically leads to increases in MO2 and JAmm during post-exercise following exhaustive exercise. Hagfish primarily relied on the gills for recovery; therefore, we employed exhaustive exercise to determine the relative contribution of the gills and skin to elevations in both O2 uptake (81.0%) and ammonia excretion (70.7%). Following metabolic demand. Given that skin is proposed as the primary site exercise, both O2 uptake and ammonia excretion increased, but only ̇ across the gill; cutaneous exchange was not increased. -

Echidna Catenata (Chain Moray)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology Echidna catenata (Chain Moray) Family: Muraenidae (Morays) Order: Anguilliformes (True Eels and Morays) Class: Actinopterygii (Ray-Finned Fish) Fig. 1. Chain moray, Echidna catenata. [http://claycoleman.tripod.com/id130.htm, downloaded 2 March 2016] TRAITS. Chain morays, also commonly called little banded eels (Fig. 1), typically range from a few centimetres to a maximum of 70cm (Böhlke, 2013). Their physical appearance is a long, stout, snake-like body (Fig. 2), without ventral and pectoral fins. Beginning behind the head is a continuous fin, formed from the anal, dorsal and tail fins, which includes the tail and expands midway to the belly (Humann, 1989). Its head is short with a steep profile comprising of a short and rounded snout and its eyes are either above or just at the back of its mid jaw (Böhlke, 2013). The entire body lacks scales, but is covered by a protective layer of clear mucus. With regard to colouring, chain morays have yellow eyes and bodies that are dark brown to black with asymmetrical, chain like patterns. These chain-like markings are bright yellow and can be interconnected (Humann, 1989). Since they are carnivorous, they have short, powerful jaws, but unlike other eels, their teeth are short and blunt (Fig. 3) with some being molariform (Randall, 2004). UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology DISTRIBUTION. It is widely distributed and occurs in areas ranging from Florida to the Gulf of Mexico and the Florida Keys, the western Atlantic from Bermuda and throughout the Caribbean Sea, inclusive of the Bahamas. -

Myxine Glutinosa

Atlantic Hagfish − Myxine glutinosa Overall Vulnerability Rank = Moderate Biological Sensitivity = Moderate Climate Exposure = High Data Quality = 67% of scores ≥ 2 Expert Data Expert Scores Plots Myxine glutinosa Scores Quality (Portion by Category) Low Moderate Stock Status 2.4 0.2 High Other Stressors 1.6 1.1 Very High Population Growth Rate 2.6 0.6 Spawning Cycle 1.1 2.6 Complexity in Reproduction 1.9 1.0 Early Life History Requirements 1.1 2.1 Sensitivity to Ocean Acidification 1.5 1.9 Prey Specialization 1.0 2.6 Habitat Specialization 1.2 3.0 Sensitivity attributes Sensitivity to Temperature 1.6 2.7 Adult Mobility 3.0 2.2 Dispersal & Early Life History 2.7 1.4 Sensitivity Score Moderate Sea Surface Temperature 3.9 3.0 Variability in Sea Surface Temperature 1.0 3.0 Salinity 1.4 3.0 Variability Salinity 1.2 3.0 Air Temperature 1.0 3.0 Variability Air Temperature 1.0 3.0 Precipitation 1.0 3.0 Variability in Precipitation 1.0 3.0 Ocean Acidification 4.0 2.0 Exposure variables Variability in Ocean Acidification 1.0 2.2 Currents 2.1 1.0 Sea Level Rise 1.1 1.5 Exposure Score High Overall Vulnerability Rank Moderate Atlantic Hagfish (Myxine glutinosa) Overall Climate Vulnerability Rank: Moderate (92% certainty from bootstrap analysis). Climate Exposure: High. Two exposure factors contributed to this score: Ocean Surface Temperature (3.9) and Ocean Acidification (4.0). All life stages of Atlantic Hagfish use marine habitats. Biological Sensitivity: Moderate. Two sensitivity attributes scored above 2.5: Adult Mobility (3.0) and Dispersal and Early Life History (2.7). -

Training Manual Series No.15/2018

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CMFRI Digital Repository DBTR-H D Indian Council of Agricultural Research Ministry of Science and Technology Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute Department of Biotechnology CMFRI Training Manual Series No.15/2018 Training Manual In the frame work of the project: DBT sponsored Three Months National Training in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology for Fisheries Professionals 2015-18 Training Manual In the frame work of the project: DBT sponsored Three Months National Training in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology for Fisheries Professionals 2015-18 Training Manual This is a limited edition of the CMFRI Training Manual provided to participants of the “DBT sponsored Three Months National Training in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology for Fisheries Professionals” organized by the Marine Biotechnology Division of Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI), from 2nd February 2015 - 31st March 2018. Principal Investigator Dr. P. Vijayagopal Compiled & Edited by Dr. P. Vijayagopal Dr. Reynold Peter Assisted by Aditya Prabhakar Swetha Dhamodharan P V ISBN 978-93-82263-24-1 CMFRI Training Manual Series No.15/2018 Published by Dr A Gopalakrishnan Director, Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (ICAR-CMFRI) Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute PB.No:1603, Ernakulam North P.O, Kochi-682018, India. 2 Foreword Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI), Kochi along with CIFE, Mumbai and CIFA, Bhubaneswar within the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) and Department of Biotechnology of Government of India organized a series of training programs entitled “DBT sponsored Three Months National Training in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology for Fisheries Professionals”. -

Stock Status Table

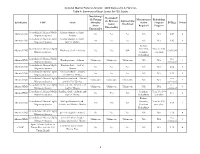

National Marine Fisheries Service - 2020 Status of U.S. Fisheries Table A. Summary of Stock Status for FSSI Stocks Overfishing? Overfished? (Is Fishing Management Rebuilding (Is Biomass Approaching Jurisdiction FMP Stock Mortality Action Program B/B Points below Overfished MSY above Required Progress Threshold?) Threshold?) Consolidated Atlantic Highly Atlantic sharpnose shark - Atlantic HMS No No No NA NA 2.08 4 Migratory Species Atlantic Consolidated Atlantic Highly Atlantic sharpnose shark - Atlantic HMS No No No NA NA 1.02 4 Migratory Species Gulf of Mexico Reduce Consolidated Atlantic Highly Mortality, Year 8 of 30- Atlantic HMS Blacknose shark - Atlantic Yes Yes NA 0.43-0.64 1 Migratory Species Continue year plan Rebuilding Consolidated Atlantic Highly not Atlantic HMS Blacktip shark - Atlantic Unknown Unknown Unknown NA NA 0 Migratory Species estimated Consolidated Atlantic Highly Blacktip shark - Gulf of Atlantic HMS No No No NA NA 2.62 4 Migratory Species Mexico Consolidated Atlantic Highly Finetooth shark - Atlantic Atlantic HMS No No No NA NA 1.30 4 Migratory Species and Gulf of Mexico Consolidated Atlantic Highly Great hammerhead - Atlantic not Atlantic HMS Unknown Unknown Unknown NA NA 0 Migratory Species and Gulf of Mexico estimated Consolidated Atlantic Highly Lemon shark - Atlantic and not Atlantic HMS Unknown Unknown Unknown NA NA 0 Migratory Species Gulf of Mexico estimated Consolidated Atlantic Highly Sandbar shark - Atlantic and Continue Year 16 of 66- Atlantic HMS No Yes NA 0.77 2 Migratory Species Gulf of Mexico -

Annotated Checklist of the Fish Species (Pisces) of La Réunion, Including a Red List of Threatened and Declining Species

Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde A, Neue Serie 2: 1–168; Stuttgart, 30.IV.2009. 1 Annotated checklist of the fish species (Pisces) of La Réunion, including a Red List of threatened and declining species RONALD FR ICKE , THIE rr Y MULOCHAU , PA tr ICK DU R VILLE , PASCALE CHABANE T , Emm ANUEL TESSIE R & YVES LE T OU R NEU R Abstract An annotated checklist of the fish species of La Réunion (southwestern Indian Ocean) comprises a total of 984 species in 164 families (including 16 species which are not native). 65 species (plus 16 introduced) occur in fresh- water, with the Gobiidae as the largest freshwater fish family. 165 species (plus 16 introduced) live in transitional waters. In marine habitats, 965 species (plus two introduced) are found, with the Labridae, Serranidae and Gobiidae being the largest families; 56.7 % of these species live in shallow coral reefs, 33.7 % inside the fringing reef, 28.0 % in shallow rocky reefs, 16.8 % on sand bottoms, 14.0 % in deep reefs, 11.9 % on the reef flat, and 11.1 % in estuaries. 63 species are first records for Réunion. Zoogeographically, 65 % of the fish fauna have a widespread Indo-Pacific distribution, while only 2.6 % are Mascarene endemics, and 0.7 % Réunion endemics. The classification of the following species is changed in the present paper: Anguilla labiata (Peters, 1852) [pre- viously A. bengalensis labiata]; Microphis millepunctatus (Kaup, 1856) [previously M. brachyurus millepunctatus]; Epinephelus oceanicus (Lacepède, 1802) [previously E. fasciatus (non Forsskål in Niebuhr, 1775)]; Ostorhinchus fasciatus (White, 1790) [previously Apogon fasciatus]; Mulloidichthys auriflamma (Forsskål in Niebuhr, 1775) [previously Mulloidichthys vanicolensis (non Valenciennes in Cuvier & Valenciennes, 1831)]; Stegastes luteobrun- neus (Smith, 1960) [previously S.