Mediterranean Sea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mediterranean Marine Science

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by National Documentation Centre - EKT journals Mediterranean Marine Science Vol. 20, 2019 Twelve new records of gobies and clingfishes (Pisces: Teleostei) significantly increase small benthic fish diversity of Maltese waters KOVAČIĆ MARCELO Natural History Museum Rijeka SCHEMBRI PATRICK University of Malta https://doi.org/10.12681/mms.19816 Copyright © 2019 Mediterranean Marine Science To cite this article: KOVAČIĆ, M., & SCHEMBRI, P. (2019). Twelve new records of gobies and clingfishes (Pisces: Teleostei) significantly increase small benthic fish diversity of Maltese waters. Mediterranean Marine Science, 20(2), 287-296. doi:https://doi.org/10.12681/mms.19816 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 23/03/2020 08:31:30 | Research Article Mediterranean Marine Science Indexed in WoS (Web of Science, ISI Thomson) and SCOPUS The journal is available on line at http://www.medit-mar-sc.net DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/mms.19816 Twelve new records of gobies and clingfishes (Pisces: Teleostei) significantly increase small benthic fish diversity of Maltese waters Marcelo KOVAČIĆ¹ and Patrick J. SCHEMBRI² ¹Natural History Museum Rijeka, Lorenzov prolaz 1, HR-51000 Rijeka ²Department of Biology, University of Malta, Msida MSD2080, Malta Corresponding author: [email protected] Handling Editor: Argyro ZENETOS Received: 25 February 2019; Accepted: 23 March 2019; Published on line: 28 May 2019 Abstract Twelve new first records of species from two families are added to the list of known marine fishes from Malta based on labo- ratory study of material collected during fieldwork over a period of more than twenty years. -

CHECKLIST and BIOGEOGRAPHY of FISHES from GUADALUPE ISLAND, WESTERN MEXICO Héctor Reyes-Bonilla, Arturo Ayala-Bocos, Luis E

ReyeS-BONIllA eT Al: CheCklIST AND BIOgeOgRAphy Of fISheS fROm gUADAlUpe ISlAND CalCOfI Rep., Vol. 51, 2010 CHECKLIST AND BIOGEOGRAPHY OF FISHES FROM GUADALUPE ISLAND, WESTERN MEXICO Héctor REyES-BONILLA, Arturo AyALA-BOCOS, LUIS E. Calderon-AGUILERA SAúL GONzáLEz-Romero, ISRAEL SáNCHEz-ALCántara Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada AND MARIANA Walther MENDOzA Carretera Tijuana - Ensenada # 3918, zona Playitas, C.P. 22860 Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur Ensenada, B.C., México Departamento de Biología Marina Tel: +52 646 1750500, ext. 25257; Fax: +52 646 Apartado postal 19-B, CP 23080 [email protected] La Paz, B.C.S., México. Tel: (612) 123-8800, ext. 4160; Fax: (612) 123-8819 NADIA C. Olivares-BAñUELOS [email protected] Reserva de la Biosfera Isla Guadalupe Comisión Nacional de áreas Naturales Protegidas yULIANA R. BEDOLLA-GUzMáN AND Avenida del Puerto 375, local 30 Arturo RAMíREz-VALDEz Fraccionamiento Playas de Ensenada, C.P. 22880 Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Ensenada, B.C., México Facultad de Ciencias Marinas, Instituto de Investigaciones Oceanológicas Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Carr. Tijuana-Ensenada km. 107, Apartado postal 453, C.P. 22890 Ensenada, B.C., México ABSTRACT recognized the biological and ecological significance of Guadalupe Island, off Baja California, México, is Guadalupe Island, and declared it a Biosphere Reserve an important fishing area which also harbors high (SEMARNAT 2005). marine biodiversity. Based on field data, literature Guadalupe Island is isolated, far away from the main- reviews, and scientific collection records, we pres- land and has limited logistic facilities to conduct scien- ent a comprehensive checklist of the local fish fauna, tific studies. -

Diurnal Patterns in Gulf of Mexico Epipelagic Predator Interactions with Pelagic Longline Gear: Implications for Target Species Catch Rates and Bycatch Mitigation

Bull Mar Sci. 93(2):573–589. 2017 research paper https://doi.org/10.5343/bms.2016.1008 Diurnal patterns in Gulf of Mexico epipelagic predator interactions with pelagic longline gear: implications for target species catch rates and bycatch mitigation 1 National Marine Fisheries Eric S Orbesen 1 * Service, Southeast Fisheries 1 Science Center, 75 Virginia Beach Derke Snodgrass 2 Drive, Miami, Florida 33149. Geoffrey S Shideler 1 2 University of Miami, Rosenstiel Craig A Brown School of Marine & Atmospheric John F Walter 1 Science, 4600 Rickenbacker Causeway, Miami, Florida 33149. * Corresponding author email: <[email protected]>. ABSTRACT.—Bycatch in pelagic longline fisheries is of substantial international concern, and the mitigation of bycatch in the Gulf of Mexico has been considered as an option to help restore lost biomass following the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill. The most effective bycatch mitigation measures operate upon a differential response between target and bycatch species, ideally maintaining target catch while minimizing bycatch. We investigated whether bycatch vs target catch rates varied between day and night sets for the United States pelagic longline fishery in the Gulf of Mexico by comparing the influence of diel time period and moon illumination on catch rates of 18 commonly caught species/species groups. A generalized linear model approach was used to account for operational and environmental covariates, including: year, season, water temperature, hook type, bait, and maximum hook depth. Time of day or moon -

Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean Volume

ISBN 0-9689167-4-x Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean (Davis Strait, Southern Greenland and Flemish Cap to Cape Hatteras) Volume One Acipenseriformes through Syngnathiformes Michael P. Fahay ii Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean iii Dedication This monograph is dedicated to those highly skilled larval fish illustrators whose talents and efforts have greatly facilitated the study of fish ontogeny. The works of many of those fine illustrators grace these pages. iv Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean v Preface The contents of this monograph are a revision and update of an earlier atlas describing the eggs and larvae of western Atlantic marine fishes occurring between the Scotian Shelf and Cape Hatteras, North Carolina (Fahay, 1983). The three-fold increase in the total num- ber of species covered in the current compilation is the result of both a larger study area and a recent increase in published ontogenetic studies of fishes by many authors and students of the morphology of early stages of marine fishes. It is a tribute to the efforts of those authors that the ontogeny of greater than 70% of species known from the western North Atlantic Ocean is now well described. Michael Fahay 241 Sabino Road West Bath, Maine 04530 U.S.A. vi Acknowledgements I greatly appreciate the help provided by a number of very knowledgeable friends and colleagues dur- ing the preparation of this monograph. Jon Hare undertook a painstakingly critical review of the entire monograph, corrected omissions, inconsistencies, and errors of fact, and made suggestions which markedly improved its organization and presentation. -

An Annotated Checklist of the Shorefishes of the Canary Islands

AMERICAN MUSEUM Novitates PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK, N.Y. 10024 Number 2824, pp. 1-49, figs. 1-5 August 7, 1985 An Annotated Checklist of the Shorefishes of the Canary Islands JAMES K. DOOLEY,' JAMES VAN TASSELL,2 AND ALBERTO BRITO3 ABSTRACT The inshore canarian fish fauna includes 217 The fish fauna contains elements from the Med- species from 67 families. Fifteen new records (in- iterranean-Atlantic and West African areas, but cluding two undescribed species) and numerous does not exhibit any clear transition. Three en- rare species have been included. The number of demic species of fishes have been confirmed. The fishes documented from the Canary Islands and families with the greatest diversification include: nearby waters total approximately 400 species. Sparidae (21 species), Scorpaenidae (1 1), Gobiidae This figure includes some 200 pelagic, deepwater, (1 1), Blenniidae (10), Serranidae (9), Carangidae and elasmobranch species not treated in this study. (9), Muraenidae (7), and Labridae (7). RESUMEN La fauna ictiologica de las aguas costeras se las en el presente trabajo. La fauna contiene elemen- Islas Canarias comprende 217 especies de 67 fa- tos de las regiones Atlantico-Mediterranea y Oeste milias. Se incluyen quince citas nuevas (incluyen Africana, pero no muestra una clara transicion. dos especies no describen) y numerosas especies Tres especie endemica existe. Las familias con ma- raras. El nu'mero de peces de las aguas canarias se yor diversificacion son: Sparidae (21 especies), eleva aproximadamente a 400 especies. Este nui- Scorpaenidae (1 1), Gobiidae (1 1), Blenniidae (10), mero incluye casi 200 especies pelagicas, de aguas Serranidae (9), Carangidae (9), Muraenidae (7), y profundas y elasmobranquios que no se discuten Labridae (7). -

First Record of the Clingfish Apletodon Dentatus (Gobiesocidae) in The

Bulletin of Fish Biology Volume 13 Nos. 1/2 30.11.2011 65-69 Short note/Kurze Mitteilung First record of the clingfi sh Apletodon dentatus (Gobiesocidae) in the Adriatic Sea and a description of a simple method to collect clingfi shes Erster Nachweis des Schildfi sches Apletodon dentatus (Gobiesocidae) in der Adria und eine Beschreibung einer simplen Fangmethode für Schildfi sche Simon Brandl1, Maximilian Wagner1, Robert Hofrichter2 & Robert A. Patzner2 1University of Innsbruck, Technikerstr. 15, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria; [email protected]; 2University of Salzburg, Hellbrunnerstr. 34, 5020 Salzburg, Austria. Zusammenfassung: Zwei Exemplare der Schildfi schart Apletodon dentatus (Facciola, 1887) wurden in der Bucht von Sv. Petar auf der Insel Krk (nördliche Adria, Kroatien) gefangen. Dies ist der erste Nachweis dieser Art in der Adria. Eine einfache und effektive Methode Schildfi sche zu fangen, besteht darin, Teller umgekehrt auf das Substrat zu legen.Diese werden von den Schildfi schen als Höhle angenommen. Clingfi shes (Gobiesocidae) are small crypto- with common methods like nets and baited benthic fi shes, characterized by a scaleless and traps, a simple but effective collecting method fl attened body, an adhesive sucking disc at the was developed. ventral body surface and the absence of a swim To examine the occurrence of clingfish bladder. There are currently eight species known species, the bay Sv. Petar at the island of Krk, in the Mediterranean Sea: Apletodon dentatus Croatia, (fi g. 1) was chosen as it provides many (Facciola, 1887), Apletodon incognitus (Hofrichter different habitats, including a sandy bottom, a & Patzner, 1997), Diplecogaster bimaculata (Bon- sea grass meadow (Cymodocea nodosa), a rocky naterre, 1788), Gouania wildenowi (Risso, 1810), slope with different kinds of brown algae and a Lepadogaster candollei (Risso, 1810), Lepadogaster rocky ground with pebbles and stones. -

Updated Checklist of Marine Fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the Proposed Extension of the Portuguese Continental Shelf

European Journal of Taxonomy 73: 1-73 ISSN 2118-9773 http://dx.doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2014.73 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2014 · Carneiro M. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9A5F217D-8E7B-448A-9CAB-2CCC9CC6F857 Updated checklist of marine fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf Miguel CARNEIRO1,5, Rogélia MARTINS2,6, Monica LANDI*,3,7 & Filipe O. COSTA4,8 1,2 DIV-RP (Modelling and Management Fishery Resources Division), Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera, Av. Brasilia 1449-006 Lisboa, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 3,4 CBMA (Centre of Molecular and Environmental Biology), Department of Biology, University of Minho, Campus de Gualtar, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] * corresponding author: [email protected] 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:90A98A50-327E-4648-9DCE-75709C7A2472 6 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:1EB6DE00-9E91-407C-B7C4-34F31F29FD88 7 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:6D3AC760-77F2-4CFA-B5C7-665CB07F4CEB 8 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:48E53CF3-71C8-403C-BECD-10B20B3C15B4 Abstract. The study of the Portuguese marine ichthyofauna has a long historical tradition, rooted back in the 18th Century. Here we present an annotated checklist of the marine fishes from Portuguese waters, including the area encompassed by the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf and the Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ). The list is based on historical literature records and taxon occurrence data obtained from natural history collections, together with new revisions and occurrences. -

Factors Influencing Habitat Selection of Three Cryptobenthic Clingfish

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Factors Influencing Habitat Selection of Three Cryptobenthic Clingfish Species in the Shallow North Adriatic Sea Domen Trkov 1,2,* , Danijel Ivajnšiˇc 3,4 , Marcelo Kovaˇci´c 5 and Lovrenc Lipej 1,2 1 Marine Biology Station Piran, National Institute of Biology, Fornaˇce41, 6330 Piran, Slovenia; [email protected] 2 Jožef Stefan Institute and Jožef Stefan International Postgraduate School, Jamova Cesta 39, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia 3 Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, University of Maribor, Koroška Cesta 160, 2000 Maribor, Slovenia; [email protected] 4 Faculty of Arts, University of Maribor, Koroška Cesta 160, 2000 Maribor, Slovenia 5 Natural History Museum Rijeka, Lorenzov Prolaz 1, 51000 Rijeka, Croatia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Cryptobenthic fishes were often overlooked in the past due to their cryptic lifestyle, so knowledge of their ecology is still incomplete. One of the most poorly studied taxa of fishes in the Mediterranean Sea is clingfish. In this paper we examine the habitat preferences of three clingfish species (Lepadogaster lepadogaster, L. candolii, and Apletodon incognitus) occurring in the Gulf of Trieste (Northern Adriatic). The results show that all three species have a cryptic lifestyle and are well- segregated based on their depth distribution and macro- and microhabitat preferences. L. lepadogaster inhabits shallow waters of the lower mediolittoral and upper infralittoral, where it occurs on rocky bottoms under stones. L. candolii similarly occurs in the rocky infralittoral under stones, but below the Citation: Trkov, D.; Ivajnšiˇc,D.; lower distribution limit of L. lepadogaster, and in seagrass meadows, where it occupies empty seashells. -

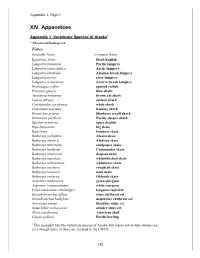

XIV. Appendices

Appendix 1, Page 1 XIV. Appendices Appendix 1. Vertebrate Species of Alaska1 * Threatened/Endangered Fishes Scientific Name Common Name Eptatretus deani black hagfish Lampetra tridentata Pacific lamprey Lampetra camtschatica Arctic lamprey Lampetra alaskense Alaskan brook lamprey Lampetra ayresii river lamprey Lampetra richardsoni western brook lamprey Hydrolagus colliei spotted ratfish Prionace glauca blue shark Apristurus brunneus brown cat shark Lamna ditropis salmon shark Carcharodon carcharias white shark Cetorhinus maximus basking shark Hexanchus griseus bluntnose sixgill shark Somniosus pacificus Pacific sleeper shark Squalus acanthias spiny dogfish Raja binoculata big skate Raja rhina longnose skate Bathyraja parmifera Alaska skate Bathyraja aleutica Aleutian skate Bathyraja interrupta sandpaper skate Bathyraja lindbergi Commander skate Bathyraja abyssicola deepsea skate Bathyraja maculata whiteblotched skate Bathyraja minispinosa whitebrow skate Bathyraja trachura roughtail skate Bathyraja taranetzi mud skate Bathyraja violacea Okhotsk skate Acipenser medirostris green sturgeon Acipenser transmontanus white sturgeon Polyacanthonotus challengeri longnose tapirfish Synaphobranchus affinis slope cutthroat eel Histiobranchus bathybius deepwater cutthroat eel Avocettina infans blackline snipe eel Nemichthys scolopaceus slender snipe eel Alosa sapidissima American shad Clupea pallasii Pacific herring 1 This appendix lists the vertebrate species of Alaska, but it does not include subspecies, even though some of those are featured in the CWCS. -

Marine Fishes of the Azores: an Annotated Checklist and Bibliography

MARINE FISHES OF THE AZORES: AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST AND BIBLIOGRAPHY. RICARDO SERRÃO SANTOS, FILIPE MORA PORTEIRO & JOÃO PEDRO BARREIROS SANTOS, RICARDO SERRÃO, FILIPE MORA PORTEIRO & JOÃO PEDRO BARREIROS 1997. Marine fishes of the Azores: An annotated checklist and bibliography. Arquipélago. Life and Marine Sciences Supplement 1: xxiii + 242pp. Ponta Delgada. ISSN 0873-4704. ISBN 972-9340-92-7. A list of the marine fishes of the Azores is presented. The list is based on a review of the literature combined with an examination of selected specimens available from collections of Azorean fishes deposited in museums, including the collection of fish at the Department of Oceanography and Fisheries of the University of the Azores (Horta). Personal information collected over several years is also incorporated. The geographic area considered is the Economic Exclusive Zone of the Azores. The list is organised in Classes, Orders and Families according to Nelson (1994). The scientific names are, for the most part, those used in Fishes of the North-eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean (FNAM) (Whitehead et al. 1989), and they are organised in alphabetical order within the families. Clofnam numbers (see Hureau & Monod 1979) are included for reference. Information is given if the species is not cited for the Azores in FNAM. Whenever available, vernacular names are presented, both in Portuguese (Azorean names) and in English. Synonyms, misspellings and misidentifications found in the literature in reference to the occurrence of species in the Azores are also quoted. The 460 species listed, belong to 142 families; 12 species are cited for the first time for the Azores. -

Otolith Atlas for the Western Mediterranean, North and Central Eastern Atlantic

SCIENTIA MARINA 72S1 July 2008, 7-198, Barcelona (Spain) ISSN: 0214-8358 Otolith atlas for the western Mediterranean, north and central eastern Atlantic VICTOR M. TUSET 1, ANTONI LOMBARTE 2 and CARLOS A. ASSIS 3 1 Instituto Canario de Ciencias Marinas, Departamento de Biología Pesquera, P.O. Box. 56, E-35200 Telde (Las Palmas), Canary Islands, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Institut de Ciències del Mar-CSIC, Departament de Recursos Marins Renovables, Passeig Marítim 37-49, Barcelona 08003, Catalonia, Spain. 3 Instituto de Oceanografia e Departamento de Biologia Animal, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Campo Grande 1749-016, Lisboa, Portugal. SUMMARY: The sagittal otolith of 348 species, belonging to 99 families and 22 orders of marine Teleostean fishes from the north and central eastern Atlantic and western Mediterranean were described using morphological and morphometric characters. The morphological descriptions were based on the otolith shape, outline and sulcus acusticus features. The mor- phometric parameters determined were otolith length (OL, mm), height (OH, mm), perimeter (P; mm) and area (A; mm2) and were expressed in terms of shape indices as circularity (P2/A), rectangularity (A/(OL×OH)), aspect ratio (OH/OL; %) and OL/fish size. The present Atlas provides information that complements the characterization of some ichthyologic taxa. In addition, it constitutes an important instrument for species identification using sagittal otoliths collected in fossiliferous layers, in archaeological sites or in feeding remains of bony fish predators. Keywords: otolith, sagitta, morphology, morphometry, western Mediterranean, north eastern Atlantic, central eastern Atlantic. RESUMEN: Otolitos de peces del mediterráneo occidental y del atlántico central y nororiental. -

FAMILY Ophichthidae Gunther, 1870

FAMILY Ophichthidae Gunther, 1870 - snake eels and worm eels SUBFAMILY Myrophinae Kaup, 1856 - worm eels [=Neenchelidae, Aoteaidae, Muraenichthyidae, Benthenchelyini] Notes: Myrophinae Kaup, 1856a:53 [ref. 2572] (subfamily) Myrophis [also Kaup 1856b:29 [ref. 2573]] Neenchelidae Bamber, 1915:478 [ref. 172] (family) Neenchelys [corrected to Neenchelyidae by Jordan 1923a:133 [ref. 2421], confirmed by Fowler 1934b:163 [ref. 32669], by Myers & Storey 1956:21 [ref. 32831] and by Greenwood, Rosen, Weitzman & Myers 1966:393 [ref. 26856]] Aoteaidae Phillipps, 1926:533 [ref. 6447] (family) Aotea [Gosline 1971:124 [ref. 26857] used Aotidae; family name sometimes seen as Aoteidae or Aoteridae] Muraenichthyidae Whitley, 1955b:110 [ref. 4722] (family) Muraenichthys [name only, used as valid before 2000?; not available] Benthenchelyini McCosker, 1977:13, 57 [ref. 6836] (tribe) Benthenchelys GENUS Ahlia Jordan & Davis, 1891 - worm eels [=Ahlia Jordan [D. S.] & Davis [B. M.], 1891:639] Notes: [ref. 2437]. Fem. Myrophis egmontis Jordan, 1884. Type by original designation (also monotypic). •Valid as Ahlia Jordan & Davis, 1891 -- (McCosker et al. 1989:272 [ref. 13288], McCosker 2003:732 [ref. 26993], McCosker et al. 2012:1191 [ref. 32371]). Current status: Valid as Ahlia Jordan & Davis, 1891. Ophichthidae: Myrophinae. Species Ahlia egmontis (Jordan, 1884) - key worm eel [=Myrophis egmontis Jordan [D. S.], 1884:44, Leptocephalus crenatus Strömman [P. H.], 1896:32, Pl. 3 (figs. 4-5), Leptocephalus hexastigma Regan [C. T.] 1916:141, Pl. 7 (fig. 6), Leptocephalus humilis Strömman [P. H.], 1896:29, Pl. 2 (figs. 7-9), Myrophis macrophthalmus Parr [A. E.], 1930:10, Fig. 1 (bottom), Myrophis microps Parr [A. E.], 1930:11, Fig. 1 (top)] Notes: [Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia v.