Marine Science Training Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. Kitts Final Report

ReefFix: An Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) Ecosystem Services Valuation and Capacity Building Project for the Caribbean ST. KITTS AND NEVIS FIRST DRAFT REPORT JUNE 2013 PREPARED BY PATRICK I. WILLIAMS CONSULTANT CLEVERLY HILL SANDY POINT ST. KITTS PHONE: 1 (869) 765-3988 E-MAIL: [email protected] 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. Table of Contents 3 List of Figures 6 List of Tables 6 Glossary of Terms 7 Acronyms 10 Executive Summary 12 Part 1: Situational analysis 15 1.1 Introduction 15 1.2 Physical attributes 16 1.2.1 Location 16 1.2.2 Area 16 1.2.3 Physical landscape 16 1.2.4 Coastal zone management 17 1.2.5 Vulnerability of coastal transportation system 19 1.2.6 Climate 19 1.3 Socio-economic context 20 1.3.1 Population 20 1.3.2 General economy 20 1.3.3 Poverty 22 1.4 Policy frameworks of relevance to marine resource protection and management in St. Kitts and Nevis 23 1.4.1 National Environmental Action Plan (NEAP) 23 1.4.2 National Physical Development Plan (2006) 23 1.4.3 National Environmental Management Strategy (NEMS) 23 1.4.4 National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NABSAP) 26 1.4.5 Medium Term Economic Strategy Paper (MTESP) 26 1.5 Legislative instruments of relevance to marine protection and management in St. Kitts and Nevis 27 1.5.1 Development Control and Planning Act (DCPA), 2000 27 1.5.2 National Conservation and Environmental Protection Act (NCEPA), 1987 27 1.5.3 Public Health Act (1969) 28 1.5.4 Solid Waste Management Corporation Act (1996) 29 1.5.5 Water Courses and Water Works Ordinance (Cap. -

Caribbean Wildlife Undersea 2017

Caribbean Wildlife Undersea life This document is a compilation of wildlife pictures from The Caribbean, taken from holidays and cruise visits. Species identification can be frustratingly difficult and our conclusions must be checked via whatever other resources are available. We hope this publication may help others having similar problems. While every effort has been taken to ensure the accuracy of the information in this document, the authors cannot be held re- sponsible for any errors. Copyright © John and Diana Manning, 2017 1 Angelfishes (Pomacanthidae) Corals (Cnidaria, Anthozoa) French angelfish 7 Bipinnate sea plume 19 (Pomacanthus pardu) (Antillogorgia bipinnata) Grey angelfish 8 Black sea rod 20 (Pomacanthus arcuatus) (Plexaura homomalla) Queen angelfish 8 Blade fire coral 20 (Holacanthus ciliaris) (Millepora complanata) Rock beauty 9 Branching fire coral 21 (Holacanthus tricolor) (Millepora alcicornis) Townsend angelfish 9 Bristle Coral 21 (Hybrid) (Galaxea fascicularis) Elkhorn coral 22 Barracudas (Sphyraenidae) (Acropora palmata) Great barracuda 10 Finger coral 22 (Sphyraena barracuda) (Porites porites) Fire coral 23 Basslets (Grammatidae) (Millepora dichotoma) Fairy basslet 10 Great star coral 23 (Gramma loreto) (Montastraea cavernosa) Grooved brain coral 24 Bonnetmouths (Inermiidae) (Diploria labyrinthiformis) Boga( Inermia Vittata) 11 Massive starlet coral 24 (Siderastrea siderea) Bigeyes (Priacanthidae) Pillar coral 25 Glasseye snapper 11 (Dendrogyra cylindrus) (Heteropriacanthus cruentatus) Porous sea rod 25 (Pseudoplexaura -

A Review of Blue Crab Predators Status: TAES San Antonio Phone: 830-214-5878 Note: E-Mail: [email protected]

********************************************************************* ********************************************************************* Document-ID: 2225347 Patron: Note: NOTICE: ********************************************************************* ********************************************************************* Pages: 16 Printed: 02-22-12 11:45:34 Sender: Ariel/Windows Journal Title: proceedings of the blue crab 2/22/2012 8:35 AM , mortality symposium (ult state marine fisheries (Please update within 24 hours) commission publication) Ceil! #: SH380.45. L8 858 1999 Volume: Issue: 90 Month/Year: Pages: Nof Wanted 08/19/2012 Da~e: l' Article Author: Guillory, V and M Elliot Article Title: A review of blue crab predators Status: TAES San Antonio Phone: 830-214-5878 Note: E-mail: [email protected] Name: Bandel, Micaela T AES San Antonio 2632 Broadway, Suite 301 South San Antonio, TX 78215 I '' I i' Proceedings ofthe Blue Crab Symposium 69-83 n of d A Review of Blue Crab Predators \n. I ~s VINCENT GUILLORY AND MEGAN ELLIOT B- Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, P.O. Box 189, Bourg, Lou,,fana 70343 Abstract. - The diverse life history stages, abundance, and wide distributio> over a variety of habitats are attributes that expose blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus Rathbun) to nuinerous predators. An extensive literature search was undertaken on food habits of marine and estuarin,· invertebrate, and vertebrate species to identify predators of blue crab zoea, megalopae, and juveni k/adults. Ninety three species, which included invertebrates, fish, reptiles, birds, and mammals, were documented to prey upon blue crabs. An additional l l 9 sp~cies had other crab species or brachyur:m remains in their stomach contents. More fish species were identified as blue crab predators than any other taxonomic group (67), and 60 fish species were documented to prey upon unidentified crabs and/or brachyurans. -

Echidna Catenata (Chain Moray)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology Echidna catenata (Chain Moray) Family: Muraenidae (Morays) Order: Anguilliformes (True Eels and Morays) Class: Actinopterygii (Ray-Finned Fish) Fig. 1. Chain moray, Echidna catenata. [http://claycoleman.tripod.com/id130.htm, downloaded 2 March 2016] TRAITS. Chain morays, also commonly called little banded eels (Fig. 1), typically range from a few centimetres to a maximum of 70cm (Böhlke, 2013). Their physical appearance is a long, stout, snake-like body (Fig. 2), without ventral and pectoral fins. Beginning behind the head is a continuous fin, formed from the anal, dorsal and tail fins, which includes the tail and expands midway to the belly (Humann, 1989). Its head is short with a steep profile comprising of a short and rounded snout and its eyes are either above or just at the back of its mid jaw (Böhlke, 2013). The entire body lacks scales, but is covered by a protective layer of clear mucus. With regard to colouring, chain morays have yellow eyes and bodies that are dark brown to black with asymmetrical, chain like patterns. These chain-like markings are bright yellow and can be interconnected (Humann, 1989). Since they are carnivorous, they have short, powerful jaws, but unlike other eels, their teeth are short and blunt (Fig. 3) with some being molariform (Randall, 2004). UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology DISTRIBUTION. It is widely distributed and occurs in areas ranging from Florida to the Gulf of Mexico and the Florida Keys, the western Atlantic from Bermuda and throughout the Caribbean Sea, inclusive of the Bahamas. -

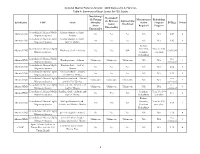

Stock Status Table

National Marine Fisheries Service - 2020 Status of U.S. Fisheries Table A. Summary of Stock Status for FSSI Stocks Overfishing? Overfished? (Is Fishing Management Rebuilding (Is Biomass Approaching Jurisdiction FMP Stock Mortality Action Program B/B Points below Overfished MSY above Required Progress Threshold?) Threshold?) Consolidated Atlantic Highly Atlantic sharpnose shark - Atlantic HMS No No No NA NA 2.08 4 Migratory Species Atlantic Consolidated Atlantic Highly Atlantic sharpnose shark - Atlantic HMS No No No NA NA 1.02 4 Migratory Species Gulf of Mexico Reduce Consolidated Atlantic Highly Mortality, Year 8 of 30- Atlantic HMS Blacknose shark - Atlantic Yes Yes NA 0.43-0.64 1 Migratory Species Continue year plan Rebuilding Consolidated Atlantic Highly not Atlantic HMS Blacktip shark - Atlantic Unknown Unknown Unknown NA NA 0 Migratory Species estimated Consolidated Atlantic Highly Blacktip shark - Gulf of Atlantic HMS No No No NA NA 2.62 4 Migratory Species Mexico Consolidated Atlantic Highly Finetooth shark - Atlantic Atlantic HMS No No No NA NA 1.30 4 Migratory Species and Gulf of Mexico Consolidated Atlantic Highly Great hammerhead - Atlantic not Atlantic HMS Unknown Unknown Unknown NA NA 0 Migratory Species and Gulf of Mexico estimated Consolidated Atlantic Highly Lemon shark - Atlantic and not Atlantic HMS Unknown Unknown Unknown NA NA 0 Migratory Species Gulf of Mexico estimated Consolidated Atlantic Highly Sandbar shark - Atlantic and Continue Year 16 of 66- Atlantic HMS No Yes NA 0.77 2 Migratory Species Gulf of Mexico -

MURAENIDAE Moray Eels by E.B

click for previous page 700 Bony Fishes MURAENIDAE Moray eels by E.B. Böhlke (deceased), Academy of Natural Sciences, Pennsylvania, USA proofs checked by D.G. Smith, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C., USA iagnostic characters: Body elongate, muscular, and laterally compressed. Dorsal profile of head Dabove and behind eye often raised due to the development of strong head muscles. Eye well devel- oped, above and near midgape. Snout short to elongate. Anterior nostril tubular, near tip of snout; posterior nostril above or before eye, a simple pore or in a tube. Mouth large, gape usually extending behind poste- rior margin of eye, lips without flanges. Teeth numerous and strong, with smooth or serrate margins, ranging from blunt rounded molars to long, slender, sharply pointed, and sometimes depressible canines;jaws short to elongate, usually about equal. On upper jaw, intermaxillary (anterior) teeth in 1 or 2 peripheral rows and usu- ally a median row of 1 to 3 teeth which are the longest in the mouth (sometimes missing in large specimens); maxillary (lateral) teeth in 1 or 2 rows on side of jaws;vomerine teeth (on roof of mouth) usually short and small, in 1 or 2 rows or in a patch, or sometimes absent. Dentary (lower jaw) teeth in 1 or more rows; in many species in the subfamily Muraeninae the first 4 teeth are larger, sometimes forming a short inner row. Gill opening a small round hole or slit at midside. Dorsal and anal fins variously developed, from long fins with dorsal fin usually beginning on head and anal fin immediately behind anus (subfamily Muraeninae), to both fins re- stricted to tail tip (subfamily Uropterygiinae); dorsal and anal fins continuous with caudal fin around tail tip; pectoral and pelvic fins absent. -

Federal Register/Vol. 70, No. 208/Friday, October 28, 2005/Rules

Federal Register / Vol. 70, No. 208 / Friday, October 28, 2005 / Rules and Regulations 62073 the Act, the Unfunded Mandates Reform nurse staffing data. This final rule will (A) Clear and readable format. Act of 1995 (Pub. L. 104–4), and have no consequential effect on the (B) In a prominent place readily Executive Order 13132. Executive Order governments mentioned or on the accessible to residents and visitors. 12866 directs agencies to assess all costs private sector. (3) Public access to posted nurse and benefits of available regulatory Executive Order 13132 establishes staffing data. The facility must, upon alternatives and, if regulation is certain requirements that an agency oral or written request, make nurse necessary, to select regulatory must meet when it promulgates a staffing data available to the public for approaches that maximize net benefits proposed rule (and subsequent final review at a cost not to exceed the (including potential economic, rule) that imposes substantial direct community standard. environmental, public health and safety requirement costs on State and local (4) Facility data retention effects, distributive impacts, and governments, preempts State law, or requirements. The facility must equity). A regulatory impact analysis otherwise has Federalism implications. maintain the posted daily nurse staffing (RIA) must be prepared for major rules Since this regulation will not impose data for a minimum of 18 months, or as with economically significant effects any costs on State or local governments, required by State law, whichever is ($100 million or more in any one year). the requirements of Executive Order greater. This rule does not reach the economic 13132 are not applicable. -

Baseline Ecological Inventory for Three Bays National Park, Haiti OCTOBER 2016

Baseline Ecological Inventory for Three Bays National Park, Haiti OCTOBER 2016 Report for the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) 1 To cite this report: Kramer, P, M Atis, S Schill, SM Williams, E Freid, G Moore, JC Martinez-Sanchez, F Benjamin, LS Cyprien, JR Alexis, R Grizzle, K Ward, K Marks, D Grenda (2016) Baseline Ecological Inventory for Three Bays National Park, Haiti. The Nature Conservancy: Report to the Inter-American Development Bank. Pp.1-180 Editors: Rumya Sundaram and Stacey Williams Cooperating Partners: Campus Roi Henri Christophe de Limonade Contributing Authors: Philip Kramer – Senior Scientist (Maxene Atis, Steve Schill) The Nature Conservancy Stacey Williams – Marine Invertebrates and Fish Institute for Socio-Ecological Research, Inc. Ken Marks – Marine Fish Atlantic and Gulf Rapid Reef Assessment (AGRRA) Dave Grenda – Marine Fish Tampa Bay Aquarium Ethan Freid – Terrestrial Vegetation Leon Levy Native Plant Preserve-Bahamas National Trust Gregg Moore – Mangroves and Wetlands University of New Hampshire Raymond Grizzle – Freshwater Fish and Invertebrates (Krystin Ward) University of New Hampshire Juan Carlos Martinez-Sanchez – Terrestrial Mammals, Birds, Reptiles and Amphibians (Françoise Benjamin, Landy Sabrina Cyprien, Jean Roudy Alexis) Vermont Center for Ecostudies 2 Acknowledgements This project was conducted in northeast Haiti, at Three Bays National Park, specifically in the coastal zones of three communes, Fort Liberté, Caracol, and Limonade, including Lagon aux Boeufs. Some government departments, agencies, local organizations and communities, and individuals contributed to the project through financial, intellectual, and logistical support. On behalf of TNC, we would like to express our sincere thanks to all of them. First, we would like to extend our gratitude to the Government of Haiti through the National Protected Areas Agency (ANAP) of the Ministry of Environment, and particularly Minister Dominique Pierre, Ministre Dieuseul Simon Desras, Mr. -

Fishery Conservation and Management Pt. 622, App. A

Fishery Conservation and Management Pt. 622, App. A vessel's unsorted catch of Gulf reef to complete prohibition), and seasonal fish: or area closures. (1) The requirement for a valid com- (g) South Atlantic golden crab. MSY, mercial vessel permit for Gulf reef fish ABC, TAC, quotas (including quotas in order to sell Gulf reef fish. equal to zero), trip limits, minimum (2) Minimum size limits for Gulf reef sizes, gear regulations and restrictions, fish. permit requirements, seasonal or area (3) Bag limits for Gulf reef fish. closures, time frame for recovery of (4) The prohibition on sale of Gulf golden crab if overfished, fishing year reef fish after a quota closure. (adjustment not to exceed 2 months), (b) Other provisions of this part not- observer requirements, and authority withstanding, a dealer in a Gulf state for the RD to close the fishery when a is exempt from the requirement for a quota is reached or is projected to be dealer permit for Gulf reef fish to re- reached. ceive Gulf reef fish harvested from the (h) South Atlantic shrimp. Certified Gulf EEZ by a vessel in the Gulf BRDs and BRD specifications. groundfish trawl fishery. [61 FR 34934, July 3, 1996, as amended at 61 FR 43960, Aug. 27, 1996; 62 FR 13988, Mar. 25, § 622.48 Adjustment of management 1997; 62 FR 18539, Apr. 16, 1997] measures. In accordance with the framework APPENDIX A TO PART 622ÐSPECIES procedures of the applicable FMPs, the TABLES RD may establish or modify the follow- TABLE 1 OF APPENDIX A TO PART 622Ð ing management measures: CARIBBEAN CORAL REEF RESOURCES (a) Caribbean coral reef resources. -

Final Report

Final Report i TABLE OF CONTENTS REPORT CREDITS ................................................................................................................................. IV EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 2 METHODS .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Plants ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 Birds ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Mammals ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Reptiles and Amphibians ................................................................................................................................. 3 Aquatic (Marine) .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Aquatic (Freshwater, Estuarine, Coastal Nearshore) ....................................................................................... -

CARIBBEAN MARINE BIODIVERSITY PROGRAM Cooperative Agreement No

Atlantic and Gulf Rapid Reef Assessment CARIBBEAN MARINE BIODIVERSITY PROGRAM Cooperative Agreement No. AID-OAA-A14-00064 Reef biophysical conditions across CMBP seascapes (2019) Submitted March 15, 2019 This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of The Nature Conservancy and its partners (CEBSE, FOPROBIM, C-CAM, and SusGren) and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Acknowledgements We are grateful to the many colleagues who helped conduct the 2015 and 2018 AGRRA surveys, and the boat captains, crew and SCUBA tank providers who enabled our diving safety. Emma Doyle, Giselle Hall, Patricia Kramer, Kenneth Marks and Aurelio Reyes are especially thanked for sharing insightful information during the drafting of this report. Citation Lang, Judith C. and Lynnette M. Roth. 2019. Reef biophysical conditions across CMBP seascapes. CARIBBEAN MARINE BIODIVERSITY PROGRAM Cooperative Agreement No. AID-OAA-A14-00064. 16+i pp. A benthic surveyor conducts a transect on a shoal reef lobe in the Bluefields Bay Special Fishery Conservation Area; a fish survey transect tape can be seen in the background. L. Meggs, 2018 ON THE COVER: Brown and white spotted moray and plate coral, macroalgae, turf algae and peyssonnelids, K. Marks, 2015 i TABLE OF CONTENTS page Jamaica: CMBP Coral Reef Index Sites and Condition Indicators…………...….……………………..……1 Haiti: CMBP Coral Reef Index Sites -

Vol. 76 Thursday, No. 135 July 14, 2011 Pages 41375–41588

Vol. 76 Thursday, No. 135 July 14, 2011 Pages 41375–41588 OFFICE OF THE FEDERAL REGISTER VerDate Mar 15 2010 18:58 Jul 13, 2011 Jkt 223001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\14JYWS.LOC 14JYWS sroberts on DSK5SPTVN1PROD with RULES II Federal Register / Vol. 76, No. 135 / Thursday, July 14, 2011 The FEDERAL REGISTER (ISSN 0097–6326) is published daily, SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Monday through Friday, except official holidays, by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records PUBLIC Administration, Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Subscriptions: Act (44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) and the regulations of the Administrative Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Committee of the Federal Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Assistance with public subscriptions 202–512–1806 Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 is the exclusive distributor of the official General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 edition. Periodicals postage is paid at Washington, DC. Single copies/back copies: The FEDERAL REGISTER provides a uniform system for making Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Assistance with public single copies 1–866–512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and (Toll-Free) Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general FEDERAL AGENCIES applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published Subscriptions: by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public interest. Paper or fiche 202–741–6005 Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions 202–741–6005 Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the issuing agency requests earlier filing.