Latvia and the United States: a New Chapter in the Partnership

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Systems in Transition

61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 1 03/03/2020 09:55 Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Vol. Health Systems in Transition Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Health Systems in Transition: in Transition: Health Systems C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Latvia Latvia Health system review Daiga Behmane Alina Dudele Anita Villerusa Janis Misins The Observatory is a partnership, hosted by WHO/Europe, which includes other international organizations (the European Commission, the World Bank); national and regional governments (Austria, Belgium, Finland, Kristine Klavina Ireland, Norway, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the Veneto Region of Italy); other health system organizations (the French National Union of Health Insurance Funds (UNCAM), the Dzintars Mozgis Health Foundation); and academia (the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and the Giada Scarpetti London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM)). The Observatory has a secretariat in Brussels and it has hubs in London at LSE and LSHTM) and at the Berlin University of Technology. HiTs are in-depth profiles of health systems and policies, produced using a standardized approach that allows comparison across countries. They provide facts, figures and analysis and highlight reform initiatives in progress. Print ISSN 1817-6119 Web ISSN 1817-6127 61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 2 03/03/2020 09:55 Giada Scarpetti (Editor), and Ewout van Ginneken (Series editor) were responsible for this HiT Editorial Board Series editors Reinhard Busse, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Josep Figueras, European -

Download Download

Ajalooline Ajakiri, 2016, 3/4 (157/158), 477–511 Historical consciousness, personal life experiences and the orientation of Estonian foreign policy toward the West, 1988–1991 Kaarel Piirimäe and Pertti Grönholm ABSTRACT The years 1988 to 1991 were a critical juncture in the history of Estonia. Crucial steps were taken during this time to assure that Estonian foreign policy would not be directed toward the East but primarily toward the integration with the West. In times of uncertainty and institutional flux, strong individuals with ideational power matter the most. This article examines the influence of For- eign Minister Lennart Meri’s and Prime Minister Edgar Savisaar’s experienc- es and historical consciousness on their visions of Estonia’s future position in international affairs. Life stories help understand differences in their horizons of expectation, and their choices in conducting Estonian diplomacy. Keywords: historical imagination, critical junctures, foreign policy analysis, So- viet Union, Baltic states, Lennart Meri Much has been written about the Baltic states’ success in breaking away from Eastern Europe after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, and their decisive “return to the West”1 via radical economic, social and politi- Research for this article was supported by the “Reimagining Futures in the European North at the End of the Cold War” project which was financed by the Academy of Finland. Funding was also obtained from the “Estonia, the Baltic states and the Collapse of the Soviet Union: New Perspectives on the End of the Cold War” project, financed by the Estonian Research Council, and the “Myths, Cultural Tools and Functions – Historical Narratives in Constructing and Consolidating National Identity in 20th and 21st Century Estonia” project, which was financed by the Turku Institute for Advanced Studies (TIAS, University of Turku). -

Akasvayu Girona

AKASVAYU GIRONA OFFICIAL CLUB NAME: CVETKOVIC BRANKO 1.98 GUARD C.B. Girona SAD Born: March 5, 1984, in Gracanica, Bosnia-Herzegovina FOUNDATION YEAR: 1962 Career Notes: grew up with Spartak Subotica (Serbia) juniors…made his debut with Spartak Subotica during the 2001-02 season…played there till the 2003-04 championship…signed for the 2004-05 season by KK Borac Cacak…signed for the 2005-06 season by FMP Zeleznik… played there also the 2006-07 championship...moved to Spain for the 2007-08 season, signed by Girona CB. Miscellaneous: won the 2006 Adriatic League with FMP Zeleznik...won the 2007 TROPHY CASE: TICKET INFORMATION: Serbian National Cup with FMP Zeleznik...member of the Serbian National Team...played at • FIBA EuroCup: 2007 RESPONSIBLE: Cristina Buxeda the 2007 European Championship. PHONE NUMBER: +34972210100 PRESIDENT: Josep Amat FAX NUMBER: +34972223033 YEAR TEAM G 2PM/A PCT. 3PM/A PCT. FTM/A PCT. REB ST ASS BS PTS AVG VICE-PRESIDENTS: Jordi Juanhuix, Robert Mora 2001/02 Spartak S 2 1/1 100,0 1/7 14,3 1/4 25,0 2 0 1 0 6 3,0 GENERAL MANAGER: Antonio Maceiras MAIN SPONSOR: Akasvayu 2002/03 Spartak S 9 5/8 62,5 2/10 20,0 3/9 33,3 8 0 4 1 19 2,1 MANAGING DIRECTOR: Antonio Maceiras THIRD SPONSOR: Patronat Costa Brava 2003/04 Spartak S 22 6/15 40,0 1/2 50,0 2/2 100 4 2 3 0 17 0,8 TEAM MANAGER: Martí Artiga TECHNICAL SPONSOR: Austral 2004/05 Borac 26 85/143 59,4 41/110 37,3 101/118 85,6 51 57 23 1 394 15,2 FINANCIAL DIRECTOR: Victor Claveria 2005/06 Zeleznik 15 29/56 51,8 13/37 35,1 61/79 77,2 38 32 7 3 158 10,5 MEDIA: 2006/07 Zeleznik -

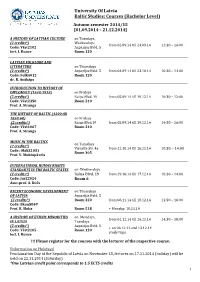

University of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level)

University Of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level) Autumn semester 2014/15 [01.09.2014 – 21.12.2014] A HISTORY OF LATVIAN CULTURE on Tuesdays, (2 credits*) Wednesdays from 02.09.14 till 24.09.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst2102 Azpazijas Bvld. 5 lect. I. Runce Room 120 LATVIAN FOLKLORE AND LITERATURE on Thursdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. 5 from 04.09.14 till 23.10.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: Folk4012 Room 120 dr. R. Auškāps INTRODUCTION TO HISTORY OF DIPLOMACY (1648-1918) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 10:30 – 12:00 Code: Vēst2350 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga THE HISTORY OF BALTIC (1200 till 1850-60) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd.19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 14:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst1067 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga MUSIC IN THE BALTICS on Tuesdays (2 credits*) Visvalža Str. 4a from 21.10.14 till 16.12.14 10:30. – 14:00 Code : MākZ1031 Room 305 Prof. V. Muktupāvels INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS STANDARTS IN THE BALTIC STATES on Wednesdays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 29.10.14 till 17.12.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: JurZ2024 Room 6 Asoc.prof. A. Kučs RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT on Thursdays OF LATVIA Azpazijas Bvld. 5 (2 credits*) Room 320 from 06.11.14 till 18.12.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Ekon5069 Prof. B. Sloka Room 518 + Monday, 10.11.14 A HISTORY OF ETHNIC MINORITIES on Mondays, from 01.12.14 till 16.12.14 14:30 – 18:00 IN LATVIA Tuesdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. -

Parent Perceptions on Identity Formation Among Latvian Emigrant Children in England Kamerāde, D and Skubiņa, I

Growing up to belong transnationally : parent perceptions on identity formation among Latvian emigrant children in England Kamerāde, D and Skubiņa, I http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12092-4 Title Growing up to belong transnationally : parent perceptions on identity formation among Latvian emigrant children in England Authors Kamerāde, D and Skubiņa, I Type Book Section URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/49752/ Published Date 2019 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. IMISCOE Research Series Rita Kaša Inta Mieriņa Editors The Emigrant Communities of Latvia National Identity, Transnational Belonging, and Diaspora Politics IMISCOE Research Series This series is the official book series of IMISCOE, the largest network of excellence on migration and diversity in the world. It comprises publications which present empirical and theoretical research on different aspects of international migration. The authors are all specialists, and the publications a rich source of information for researchers and others involved in international migration studies. The series is published under the editorial supervision of the IMISCOE Editorial Committee which includes leading scholars from all over Europe. The series, which contains more than eighty titles already, is internationally peer reviewed which ensures that the book published in this series continue to present excellent academic standards and scholarly quality. -

Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century

US Army TRADOC TRADOC G2 Handbook No. 1 AA MilitaryMilitary GuideGuide toto TerrorismTerrorism in the Twenty-First Century US Army Training and Doctrine Command TRADOC G2 TRADOC Intelligence Support Activity - Threats Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 15 August 2007 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. 1 Summary of Change U.S. Army TRADOC G2 Handbook No. 1 (Version 5.0) A Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century Specifically, this handbook dated 15 August 2007 • Provides an information update since the DCSINT Handbook No. 1, A Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century, publication dated 10 August 2006 (Version 4.0). • References the U.S. Department of State, Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism, Country Reports on Terrorism 2006 dated April 2007. • References the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), Reports on Terrorist Incidents - 2006, dated 30 April 2007. • Deletes Appendix A, Terrorist Threat to Combatant Commands. By country assessments are available in U.S. Department of State, Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism, Country Reports on Terrorism 2006 dated April 2007. • Deletes Appendix C, Terrorist Operations and Tactics. These topics are covered in chapter 4 of the 2007 handbook. Emerging patterns and trends are addressed in chapter 5 of the 2007 handbook. • Deletes Appendix F, Weapons of Mass Destruction. See TRADOC G2 Handbook No.1.04. • Refers to updated 2007 Supplemental TRADOC G2 Handbook No.1.01, Terror Operations: Case Studies in Terror, dated 25 July 2007. • Refers to Supplemental DCSINT Handbook No. 1.02, Critical Infrastructure Threats and Terrorism, dated 10 August 2006. • Refers to Supplemental DCSINT Handbook No. -

Political Visions and Historical Scores

Founded in 1944, the Institute for Western Affairs is an interdis- Political visions ciplinary research centre carrying out research in history, political and historical scores science, sociology, and economics. The Institute’s projects are typi- cally related to German studies and international relations, focusing Political transformations on Polish-German and European issues and transatlantic relations. in the European Union by 2025 The Institute’s history and achievements make it one of the most German response to reform important Polish research institution well-known internationally. in the euro area Since the 1990s, the watchwords of research have been Poland– Ger- many – Europe and the main themes are: Crisis or a search for a new formula • political, social, economic and cultural changes in Germany; for the Humboldtian university • international role of the Federal Republic of Germany; The end of the Great War and Stanisław • past, present, and future of Polish-German relations; Hubert’s concept of postliminum • EU international relations (including transatlantic cooperation); American press reports on anti-Jewish • security policy; incidents in reborn Poland • borderlands: social, political and economic issues. The Institute’s research is both interdisciplinary and multidimension- Anthony J. Drexel Biddle on Poland’s al. Its multidimensionality can be seen in published papers and books situation in 1937-1939 on history, analyses of contemporary events, comparative studies, Memoirs Nasza Podróż (Our Journey) and the use of theoretical models to verify research results. by Ewelina Zaleska On the dispute over the status The Institute houses and participates in international research of the camp in occupied Konstantynów projects, symposia and conferences exploring key European questions and cooperates with many universities and academic research centres. -

Illicit Trafficking in Firearms, Their Parts, Components and Ammunition To, from and Across the European Union

Illicit Trafficking in Firearms, their Parts, Components and Ammunition to, from and across the European Union REGIONAL ANALYSIS REPORT 1 UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Illicit Trafficking in Firearms, their Parts, Components and Ammunition to, from and across the European Union UNITED NATIONS Vienna, 2020 UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Illicit Trafficking in Firearms, their Parts, Components and Ammunition to, from and across the European Union REGIONAL ANALYSIS REPORT UNITED NATIONS Vienna, 2020 © United Nations, 2020. All rights reserved, worldwide. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copy- right holder, provided acknowledgment of the source is made. UNODC would appreciate receiving a copy of any written output that uses this publication as a source at [email protected]. DISCLAIMERS This report was not formally edited. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNODC, nor do they imply any endorsement. Information on uniform resource locators and links to Internet sites contained in the present publication are provided for the convenience of the reader and are correct at the time of issuance. The United Nations takes no responsibility for the continued accuracy of that information or for the content of any external website. This document was produced with the financial support of the European Union. The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to reflect -

STRATEGY of “CONSTRAINMENT” Countering Russia’S Challenge to the Democratic Order

Atlantic Council STRATEGY OF “CONSTRAINMENT” Countering Russia’s Challenge to the Democratic Order PREPARED BY Ash Jain and Damon Wilson (United States) Fen Hampson and Simon Palamar (Canada) Camille Grand (France) IN COLLABORATION WITH Go Myong-Hyun (South Korea) James Nixey (United Kingdom) Michal Makocki (European Union) Nathalie Tocci (Italy) Acknowledgment The Atlantic Council would like to acknowledge the generous financial support provided by the Smith Richardson Foundation for this effort. STRATEGY OF “CONSTRAINMENT” Countering Russia’s Challenge to the Democratic Order PREPARED BY Ash Jain and Damon Wilson, Atlantic Council (United States) Fen Hampson and Simon Palamar, Centre for International Governance Innovation (Canada) Camille Grand, Foundation for Strategic Research (France) IN COLLABORATION WITH Go Myong-Hyun, Asan Institute for Policy Studies (South Korea) James Nixey, Chatham House (United Kingdom) Michal Makocki, former official, European External Action Service (European Union) Nathalie Tocci, Institute of International Affairs (Italy) © 2017 The Atlantic Council of the United States and Centre for International Governance Innovation. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Atlantic Council or Centre for International Governance Innovation, except in the case of brief quotations in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. Please direct inquiries to: Atlantic Council Centre for International Governance Innovation 1030 15th Street, NW, 12th Floor 67 Erb Street West Washington, DC 20005 Waterloo, ON, Canada N2L 6C2 ISBN: 978-1-61977-434-6 Publication design: Krystal Ferguson The views expressed in this paper reflect those solely of the co-authors. -

BALTIC SUSTAINABLE ENERGY STRATEGY Stockholm Environment Institute Tallinn Centre

BALTIC SUSTAINABLE ENERGY STRATEGY Stockholm Environment Institute Tallinn Centre Tallinn-Riga-Kaunas, 2008 This strategy is prepared during the project "Baltic-Nordic cooperation for sustainable energy" that is a joint cooperation project of environmental NGOs and experts from Baltic and Nordic countries, North-West Russia and Belarus. The project is financially supported by the Nordic Council of Ministers. Project was coordinated by the Latvian Green Movement (www.zalie.lv). Strategy was prepared by Stockholm Environment Institute Tallinn Centre (www.seit.ee) and was discussed and amended by the participants of the international seminar "Sustainable energy policy for the Baltic Sea region: non-fossil and non-nuclear opportunities" that took place on February 26, 2008 in Riga, Latvia. 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………….6 2. Baltic States power sector developments….……………………………………………8 2.1. General characteristics………………………………………………..…………….....8 2.2. Estonia………………………………………………………………………………..10 2.3. Latvia…………………………………………………………………………………19 2.4. Lithuania………………………………………………………………………….…..26 2.5. Energy intensity of Baltic States..……………………………………………………33 3. Goals for the Energy sector in the Baltic States………………………………………36 4. Sustainable Energy Strategy for Baltic States…………………………………………41 4.1. Sustainable energy indicators………………………………………………………...43 4.2. External costs of energy production………………………………………………….48 4.3. Goals of the Baltic Sustainable Energy Strategy……………………………………..52 4.4. Measures to achieve BSES Goals……………………………………………………53 -

Latvia Towards Europe: Internal Security Issues

North Atlantic Treaty Organization Andris Runcis LATVIA TOWARDS EUROPE: INTERNAL SECURITY ISSUES Final Report The preparation of this Report was made possible through a NATO Award. Rîga, 1999 1 Content Introduction 3 1. The basic aspects of a country’s security 5 2. Latvia’s security concept 8 3. Corruption 10 4. Unemployment 17 5. Non-governmental organizations 19 6. The Latvian banking system and its crisis 27 7. Citizenship issue 32 Conclusion 46 Appendix 48 2 Introduction The security of small countries has been a difficult problem since ancient times. Now, when the Cold War has ended and Europe has moved from a bipolar to a multipolar system, when the communist system in Eastern Europe has collapsed and the Soviet empire has disintegrated – processes which have led to the appearance of a series of new and mostly small countries in Europe – we are witnessing a renaissance of small countries in the international arena. Since regaining independence Latvia’s general foreign policy orientation has been associated with integration into European economic, political and military structures where full membership in the European Union (EU) is the cornerstone. The issue has been one of the most consolidated and undisputed on the country’s political agenda. Latvian politicians have stressed the country’s wish to become a member state of the European Union. On October 14, 1995, all political parties represented in the Parliament supported the State President’s proposed Declaration on the Policy of Latvian Integration in the European Union. On October 27, Latvia submitted its application for membership to the EU. -

Estonian Academy of Sciences Yearbook 2018 XXIV

Facta non solum verba ESTONIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES YEARBOOK FACTS AND FIGURES ANNALES ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARUM ESTONICAE XXIV (51) 2018 TALLINN 2019 This book was compiled by: Jaak Järv (editor-in-chief) Editorial team: Siiri Jakobson, Ebe Pilt, Marika Pärn, Tiina Rahkama, Ülle Raud, Ülle Sirk Translator: Kaija Viitpoom Layout: Erje Hakman Photos: Annika Haas p. 30, 31, 48, Reti Kokk p. 12, 41, 42, 45, 46, 47, 49, 52, 53, Janis Salins p. 33. The rest of the photos are from the archive of the Academy. Thanks to all authos for their contributions: Jaak Aaviksoo, Agnes Aljas, Madis Arukask, Villem Aruoja, Toomas Asser, Jüri Engelbrecht, Arvi Hamburg, Sirje Helme, Marin Jänes, Jelena Kallas, Marko Kass, Meelis Kitsing, Mati Koppel, Kerri Kotta, Urmas Kõljalg, Jakob Kübarsepp, Maris Laan, Marju Luts-Sootak, Märt Läänemets, Olga Mazina, Killu Mei, Andres Metspalu, Leo Mõtus, Peeter Müürsepp, Ülo Niine, Jüri Plado, Katre Pärn, Anu Reinart, Kaido Reivelt, Andrus Ristkok, Ave Soeorg, Tarmo Soomere, Külliki Steinberg, Evelin Tamm, Urmas Tartes, Jaana Tõnisson, Marja Unt, Tiit Vaasma, Rein Vaikmäe, Urmas Varblane, Eero Vasar Printed in Priting House Paar ISSN 1406-1503 (printed version) © EESTI TEADUSTE AKADEEMIA ISSN 2674-2446 (web version) CONTENTS FOREWORD ...........................................................................................................................................5 CHRONICLE 2018 ..................................................................................................................................7 MEMBERSHIP