CHARLES UNIVERSITY in PRAGUE Diplomacy and Diplomatic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

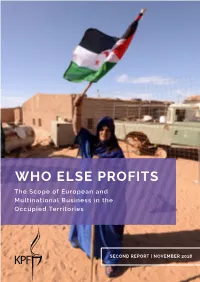

Who Else Profits the Scope of European and Multinational Business in the Occupied Territories

WHO ELSE PROFITS The Scope of European and Multinational Business in the Occupied Territories SECOND RepORT | NOVEMBER 2018 A Saharawi woman waving a Polisario-Saharawi flag at the Smara Saharawi refugee camp, near Western Sahara’s border. Photo credit: FAROUK BATICHE/AFP/Getty Images WHO ELse PROFIts The Scope of European and Multinational Business in the Occupied Territories This report is based on publicly available information, from news media, NGOs, national governments and corporate statements. Though we have taken efforts to verify the accuracy of the information, we are not responsible for, and cannot vouch, for the accuracy of the sources cited here. Nothing in this report should be construed as expressing a legal opinion about the actions of any company. Nor should it be construed as endorsing or opposing any of the corporate activities discussed herein. ISBN 978-965-7674-58-1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 WORLD MAp 7 WesteRN SAHARA 9 The Coca-Cola Company 13 Norges Bank 15 Priceline Group 18 TripAdvisor 19 Thyssenkrupp 21 Enel Group 23 INWI 25 Zain Group 26 Caterpillar 27 Biwater 28 Binter 29 Bombardier 31 Jacobs Engineering Group Inc. 33 Western Union 35 Transavia Airlines C.V. 37 Atlas Copco 39 Royal Dutch Shell 40 Italgen 41 Gamesa Corporación Tecnológica 43 NAgoRNO-KARABAKH 45 Caterpillar 48 Airbnb 49 FLSmidth 50 AraratBank 51 Ameriabank 53 ArmSwissBank CJSC 55 Artsakh HEK 57 Ardshinbank 58 Tashir Group 59 NoRTHERN CYPRUs 61 Priceline Group 65 Zurich Insurance 66 Danske Bank 67 TNT Express 68 Ford Motor Company 69 BNP Paribas SA 70 Adana Çimento 72 RE/MAX 73 Telia Company 75 Robert Bosch GmbH 77 INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION On March 24, 2016, the UN General Assembly Human Rights Council (UNHRC), at its 31st session, adopted resolution 31/36, which instructed the High Commissioner for human rights to prepare a “database” of certain business enterprises1. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2010 5 Donate.Himnadram.Org Donate.Himnadram.Org 6 HAYASTAN ALL-ARMENIAN FUND Message from Bako Sahakyan, President of the Republic of Artsakh

CONTENT BOARD OF TRUSTEES 3-8 Message from RA President 4 Message from NKR President 6 Board of Trustees 8 ACTIVITY REPORT 9-38 Executive director’s message 10 EDUCATION SECTOR 12-19 Artsakh 12 Armenia 17 HEALTHCARE SECTOR 20-25 Armenia 20 Artsakh 25 OUR SHUSHI 26-29 WATER SUPPLY 30-33 Artsakh 30 Armenia 32 RURAL DEVELOPMENT 34-35 Armenia 34 PRESIDENT’S PRIZE 36 FUNDRAISING 2010 37-38 FINANCIAL REPORT 39-56 Auditor’s report 40 Annual consolidated balance 41 Participation by countries 42 EDUCATION SECTOR 44-47 Armenia 44 Artsakh 46 EDUCATION SECTOR Armenia 48 Artsakh 49 ECONOMIC INFRASTRUCTURES 50 WATER SUPPLY 51 SOCIAL , CULTURAL AND OTHER PROJECTS Armenia 52 Artsakh 55 GOLDEN BOOK 57-59 donate.himnadram.org 2 HAYASTAN ALL-ARMENIAN FUND Board of Trustees 3 donate.himnadram.org 4 HAYASTAN ALL-ARMENIAN FUND Message from Serzh Sargsyan, President of the Republic of Armenia Throughout 2010, the Hayastan All-Armenian Fund demonstrated that it remains steadfast in realizing its extraordinary mission, that it continues to enjoy the high regard of all segments of our people. Trust of this order has been earned through as much hard work as the scale and quality of completed projects. Despite the severe economic downturn that impacted Armenia and the rest of the world in 2010, the fund not only stayed the course, but went on to raise the bar in terms of fundraising objectives. Such a singular accomplishment belongs equally to the Hayastan All-Armenian Fund and the Armenian nation as a whole. Development projects implemented in 2010 as well as ongoing initiatives are of vital and strategic significance to our people. -

Pashinyan Urges End to Anti- Government Protests in Artsakh

JUNE 9, 2018 Mirror-SpeTHE ARMENIAN ctator Volume LXXXVIII, NO. 46, Issue 4541 $ 2.00 NEWS The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 INBRIEF Pashinyan Meets with Pashinyan Urges End to Anti- Catholicos, Supreme Spiritual Council YEREVAN (Armenpress) — Prime Minister Nikol Government Protests in Artsakh Pashinyan visited the Mother See of Holy Echmiadzin where he met with the participants of STEPANAKERT (RFE/RL) — Armenia’s the annual meeting of the Supreme Spiritual Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan on Council and the Bishops’ Assembly. Monday, June 4, called for an end to anti- Karekin II, Supreme Patriarch and Catholicos of government protests in Nagorno-Karabakh All Armenians, congratulated the prime minister (Artsakh) sparked by a violent dispute on his birthday and wished him success. Touching between security officers and other local upon the recent domestic political events in residents. Armenia, Karekin II highlighted their peaceful res- Pashinyan made what he described as a olution and stated that as a result of it the coun- “brotherly request” as about 200 people try’s and people’s reputation has increased among demonstrated in Stepanakert for a fourth the international community. He expressed confi- day to demand the resignation of the heads dence that it is possible to create a powerful, pro- of Artsakh’s two main law-enforcement gressive country by the joint work of the leader- agencies blamed for the violence. ship, the church and the people. The starting incident was a brawl that Pashinyan thanked the catholicos for the warm broke out outside a Stepanakert car wash sentiments. -

The Armenian Govern - Christian Roots, the Left-To-Right Direction - Karabagh Region

OCTOBER 18, 2014 MirTHErARoMENr IAN -Spe ctator Volume LXXXV, NO. 14, Issue 4357 $ 2.00 NEWS IN BRIEF The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 Baku Furious Over Armenia’s Eurasian Accession: Security Guarantee the Game Changer French Karabagh Visit to turn down a potential association agree - point to long historical associations with BAKU (RFE/RL) — Azerbaijan is irate over a By Pietro A. Shakarian ment with the European Union (EU). Europe. These include their shared French mayor’s visit to the breakaway Nagorno- The decision by the Armenian govern - Christian roots, the left-to-right direction - Karabagh region. ment has sparked debate in Armenian ality of the Armenian alphabet, contacts The Foreign Ministry in Baku said the October YEREVAN (Hetq) — On October 10, society about the respective benefits of between the old Armenian kingdoms and 4-6 visit by the mayor of the French town of Armenia officially joined the Eurasian the two rival blocs. It is true that the West, and even the very personality of Bourg-les-Valence, Marlene Mourier, was a Customs Union. It was more than a year Armenians have long sought to integrate Charles Aznavour. In fact, to an Armenian “provocation” ahead of a meeting between the ago that the country made its fateful deci - their country with Europe and, like their or Georgian, the idea of possibly joining presidents of Azerbaijan and Armenia in Paris sion to join the Moscow-backed union and northern neighbors the Georgians, they see EURASIA, page 2 later this month. The ministry’s -

Turkey, Azerbaijan Launch Attack on Artsakh, Armenia

OCTOBER 3, 2020 MMirror-SpeirTHEror-SpeARMENIAN ctator Volume LXXXXI, NO. 12, Issue 4654 $ 2.00 NEWS The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 IN BRIEF Biden Calls on Trump APPEAL FROM THE ADL SUPREME COUNCIL Administration to Demand Turkey Stay are heading towards the border, as the homeland is in Armenia under Attack danger. Out of Conflict Therefore, the Armenian Democratic Liberal Party WASHINGTON (Public Radio of Armenia) — US Recent bellicose rhetoric by Azerbaijani and (ADL) Supreme Council condemns, in no uncertain presidential candidate Joe Biden has called on the Turkish public figures turned into acts of aggression terms, the Azerbaijani aggression, and expresses its Trump Administration to demand from Turkey to on the morning of September 27, as Azerbaijani solidarity with the people of Armenia and Artsakh. stay out of the Karabakh conflict. armed forces, violating the terms of the ceasefire, The mobilization in Armenia must take place also in “With casualties rapidly mounting in and around launched a massive attack along the line of contact, pri- the diaspora, and encourage the volunteer movement, heal the Nagorno-Karabakh, the Trump Administration marily the Artsakh-Azerbaijani border. Despite Armenia’s pow- wounded, and support the Armenian people in Artsakh and needs to call the leaders of Armenia and Azerbaijan erful retaliation, there are Armenian military and civilian casu- Armenia. Mobilization in the diaspora must lead to massive immediately to de-escalate the situation. It must alties. Hundreds are reported wounded and 16 killed. The pop- protests in front of Azerbaijani and Turkish official institutions also demand others — like Turkey — stay out of this ulations of Armenia and Artsakh (Karabakh) have been mobi- and diplomatic offices, massive news coverage to sensitize conflict,” Joe Biden said in a Twitter post. -

Amaanewsaprilmayjune2020.Pdf

AMYRIGA#I HA# AVYDARAN{AGAN UNGYRAGXOV:IVN ARMENIAN MISSIONARY ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA AMAA LIIILIV 32 April-May-June In This Issue: 2020 COVID-19 REVELATIONS By Susan Jerian, M.D. - Story Page 4 CONTENTS APRIL • MAY • JUNE 2020 /// LIV2 3 Editorial - The MISSION In the Era of COVID-19 By Zaven Khanjian 1918 2018 4 COVID-19 Revelations By Susan Jerian, M.D. 11 Inspirational Corner - Starve Your Fear, Feed Your Faith By Rev. Dr. Avedis Boynerian 12 Easter Faith By Rev. Dr. Vahan H. Tootikian AMAA NEWS 13 AMAA Executive Director/CEO Zaven Khanjian’s New York Times Square is a publication of Virtual Armenian Genocide Commemoration Message The Armenian Missionary Association of America 31 West Century Road, Paramus, NJ 07652 14 Around the Globe - Armenian Evangelical Churches of Iran Tel: (201) 265-2607; Fax: (201) 265-6015 E-mail: [email protected] 16 Meet Our Veteran Pastors - Rev. Abraham Chaparian Website: www.amaa.org (ISSN 1097-0924) 17 AMAA’s Generational Impact in Armenia and Artsakh By William Denk The AMAA is a tax-exempt, not for profit 20 Maestro Tigran Mansurian Visits AMAA’s Avedisian School in Yerevan organization under IRS Code Section 501(c)(3) 21 AMAA Executive Director/CEO Zaven Khanjian's Congratulatory Letter to Zaven Khanjian, Executive Director/CEO Arayik Harutyunyan, Newly Elected President of Artsakh Republic OFFICERS Nazareth Darakjian, M.D., President 22 David Sargsyan, Mayor of Stepanakert, Artsakh Meets with AMAA’s Michael Voskian, D.M.D., Vice President Representative in Artsakh Mark Kassabian, Esq., Co-Recording Secretary Thomas Momjian, Esq., Co-Recording Secretary 22 Meet Our Staff - Jane Wenning, AMAA News & Correspondence Support/Assistant Nurhan Helvacian, Ph.D., Treasurer 23 Central High School Alumni Association Holds 30th Anniversary Banquet EDITORIAL BOARD Zaven Khanjian, Editor in Chief 24 Rev. -

Annual Report 2017/18 Celebrating a Century of Faith, Love and Service 1918 2018 Foreword

ARMENIAN MISSIONARY ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Ամերիկայի Հայ Աւետարանչական Ընկերակցութիւն ANNUAL REPORT 2017/18 CELEBRATING A CENTURY OF FAITH, LOVE AND SERVICE 1918 2018 FOREWORD I thank God for giving me the calling to serve Him through the Armenian Missionary Association of America (AMAA) and the privilege to present to you, our supporters, friends and prayer partners, the Annual Report of the Armenian Missionary Association of America for the fiscal year 2017-2018. Pursuant to our policy of full disclosure and accountability, we have provided the Statements of Financial Position of the AMAA as of July 31, 2018, and Statements of Income and Expenditures for the past fiscal year, as prepared by our Auditors, Sax LLP, Independent Certified Public Accountants. These reports and financial statements were reviewed and acted upon at the 99th Annual Meeting of the Association held on October 20, 2018 at the United Table of Contents Armenian Congregational Church in Los Angeles, CA. Based on the approval of the reports, we have prepared this Annual Report which is available to all AMAA members, friends and supporting agencies worldwide and accessible on the AMAA website at www.amaa.org. We are grateful to God for blessing our wonderful organization for another year. We uphold all those who in the past, through their passion, dedication, sacrifice and hard work, built the foundation of AMAA. We also would like to thank all those who supported our organization with their prayers, participation and financial support during this past year. We invite you to make every effort to support your organization with greater enthusiasm, and invite others to join us in our worldwide outreach to preach the Gospel and provide a glass of cold water in His name. -

THE ARMENIAN Ctator Volume LXXXVII, NO

JUNE 10, 2017 Mirror-SpeTHE ARMENIAN ctator Volume LXXXVII, NO. 47, Issue 4491 $ 2.00 NEWS The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 INBRIEF ICG: Armenia, Azerbaijan Closer to War Over Nagorno- Georgia, Azerbaijan and Turkey to Hold Military Karabakh Than at Any Time Since 1994 Drills of the conflict in the South Caucasus, findings of analysts who had talked to resi- TBILISI (Anadoou) — Tbilisi will host military By Margarita Antidze which is criss-crossed by oil and gas dents and observers on the ground, said drills held jointly by Georgia, Azerbaijan and pipelines, have failed despite mediation led the settlement process had stalled, making Turkey this past week, the Georgian Defense by France, Russia and the United States, the use of force tempting, at least for tacti- Ministry reported. TBILISI (Reuters) — The former Soviet cal purposes, and both The Caucasus Eagle drills have been held since republics of Armenia and Azerbaijan are sides appeared ready 2009. This is the third time the exercises have been closer to war over Nagorno-Karabakh than for confrontation. held in the trilateral format. at any point since a ceasefire brokered “These tensions Earlier this May, the defense ministers of the more than 20 years ago, the International could develop into larg- three countries signed a joint statement indicating Crisis Group (ICG) said. er-scale conflict, lead- the parties’ willingness to continue efforts on Fighting between ethnic Azeris and ing to significant civil- securing stability and peace and recognizing the Armenians first erupted in 1991 and a ian casualties and pos- territorial integrity of each of the three countries. -

Life After Babylon

MARCH 16, 2019 Mirror-SpeTHE ARMENIAN ctator Volume LXXXIX, NO. 34, Issue 4578 $ 2.00 NEWS The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 INBRIEF Putin, Pashinyan Appeals Court in Armenia Rejects Spokespersons Meet in Russia Sergio Nahabedian’s Suit against ADL MOSCOW (Armenpress) — Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s spokesperson Vladimir YEREVAN (Azg) — On February 20, the Court of Republic of Armenia, be changed. Karapetyan in Moscow on a working visit, met with Appeals of the Republic of Armenia rejected an The same individual in February 2018 had applied President Vladimir Putin’s spokesperson Dmitry appeal by Sergio Nahabedian of Argentina against to a court of general jurisdiction of the city of Peskov, according to the embassy. Armenia’s the Democratic Liberal Party (ADL) of Armenia. Yerevan, which by its decision of December 13, 2018 Ambassador to Russia Vardan Toghanyan also took Nahabedian, representing himself as the completely rejected the plaintiff’s case. The rejection part in the meeting. “Chairman of the Democratic Liberal Party,” had of the plaintiff by the Appeals Court confirms explicit- During the meeting various issues regarding submitted a protest to the court demanding that the ly that the claims of the plaintiff and his “executive” to be cooperation between the press services of the two name, coat of arms and seal of the Democratic Liberal legal heirs of the ADL founded in Constantinople in 1921 are sides were discussed. Particularly, the sides Party, which are recorded in the bylaws of the party and baseless attempts to change the bylaws of the party which addressed the partnership between the press ser- ratified by the appropriate governmental body of the have been legally registered in Armenia. -

War Shows No Sign of Abating

NOVEMBER 7, 2020 MMirror-SpeirTHEror-SpeARMENIAN ctator Volume LXXXXI, NO. 17, Issue 4659 $ 2.00 NEWS The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 IN BRIEF Kocharyan Contracts Tekeyan Cultural Association Allocates $100,000 COVID To Armenia Fund to Support Artsakh YEREVAN (RFE/RL) — Despite no obstacles WATERTOWN — At an urgently convened Central Board meeting, the Tekeyan Cultural Association from the government Armenia’s former President of the United States and Canada (TCA) voted to allocate $100,000 to the Armenia Fund in support of Robert Kocharyan has not been able to leave for the Republic of Nagorno Karabakh (Artsakh). This decision was taken in light of Karabakh’s existen- Moscow for “discussions with Russian elites” tial struggle which has mobilized the entire Armenian people around the world. over ways to end the Nagorno-Karabakh war due see SUPPORT, page 12 to testing positive for the novel coronavirus, his office said on Friday, October 30. Earlier, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s spokesperson Mane Gevorkyan revealed that still on October 20 the current Armenian leader effec- War Shows tively gave the green light to Kocharyan and another former Armenian President Levon Ter- Petrosian to use their ties and political clout in Russia to get concrete proposals for ending hos- No Sign of tilities with Azerbaijan in Nagorno-Karabakh. “Stressing that he could not raise objections to any possible step for the benefit of Armenia and Abating Nagorno-Karabakh, Prime Minister Pashinyan agreed to that proposal,” said Gevorkyan, adding that according to her information neither Kocharyan nor Increased Turkish, Ter-Petrosian have made the trip yet. -

Making Immigration Great Again at Tribute to Afeyan

SEPTEMBER 28, 2019 Mirror-SpeTHE ARMENIAN ctator Volume LXXXX, NO. 11, Issue 4604 $ 2.00 NEWS The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 INBRIEF Foreign Minister Meets Pashinyan, With OSCE Minsk Former Security Group Co-Chairs NEW YORK (Armenpress) — Armenian Foreign Chief Step Up Minister Zohrab Mnatsakanyan, in New York on a working visit to take part in the 74th session of the UN General Assembly, on September 23 met with War of Words the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Minsk Group Co-Chairs Igor Popov YEREVAN (RFE/RL) — Prime Minister of the Russian Federation, Stéphane Visconti of Nikol Pashinyan and Artur Vanetsyan, the France, and Andrew Schofer of the United States of former head of Armenia’s National Security America, as well as Andrzej Kasprzyk, the Personal Service (NSS) forced to resign last week, have Representative of the OSCE Chairperson-in-Office. traded fresh and more bitter recriminations. The sides touched upon the developments fol- Vanetsyan hit out at Pashinyan when he lowing the Washington meeting on June 20, the announced his resignation in a statement current situation of the peaceful settlement process issued on September 16. He said that the of the Nagorno Karabakh conflict and the oppor- latter’s “impulsive” leadership style is not tunities to implement the agreements reached pre- good for Armenia and runs counter to the viously. NSS “officer’s honor.” Mnatsakanyan and the OSCE Minsk Group Co- Pashinyan swiftly rounded on Vanetsyan Chairs exchanged views on the upcoming meeting through his press secretary. His chief of of the Armenian and Azerbaijani FMs, as well as staff said afterwards the former NSS chief touched upon the upcoming actions planned in the co-chairs’ calendar. -

Dr. Anahit Khosroeva, Center for Assyrian Genocide Studies, Chicago, 2007, 127 Pages

Anahit Khosroeva, PhD CURRICULUM VITAE Anahit Khosroeva, Ph.D. Full Legal Name: Anahit Khosroeva Telephone, etc.: +37410-529263/work/, E-mail: [email protected] Languages: Armenian, Russian, English, Assyrian (Limited) Education: 2003 Ph.D. on Assyrian Genocide Studies, Institute of Oriental Studies, National Academy of Sciences, Republic of Armenia 1998-2003 Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences, Republic of Armenia 1994-1998 M.A, General History, Armenian State Teacher’s Training University, Yerevan city, Republic of Armenia 1982-1992 High school, Vanadzor city, Republic of Armenia Title of Ph.D. Thesis: The Assyrian Massacres in the Ottoman Turkey and on the Turkish Territories of Iran (late 19th – the first quarter of the 20th century) 1 Anahit Khosroeva, PhD EMPLOYMENT: 2015 – Present Leading Researcher at the Department of Armenian Genocide Studies, Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences, Republic of Armenia 2013 - Currently Associate Professor at Yerevan State University, Armenia 2003 – 2015 Senior researcher at the Department of Armenian Genocide Studies, Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences, Republic of Armenia 2006 – Currently Scholar in residence, Center for Middle Eastern Studies, North Park University of Chicago, USA 2004 - 2006 Associate Professor at “Haybusak” University, Yerevan, Armenia HONORS, AWARDS & MEDALS: 2019 For the services provided to Assyrian people awarded with special plaque “In Him we grow”, Sydney - St. Narsai Assyrian Christian College, Australia 2019 For the