Shared Governance at Lincoln University: an Elusive Quarry James L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faculty of the Department of Psychology West Chester University Dr

Faculty of the Department of Psychology West Chester University Dr. Sandra Kerr, Ph.D., Chairperson Dr. Vanessa Johnson, Ph.D., Assistant Chairperson Dr. Angela Clarke, Ph.D., Director of Clinical Training, Clinical Psychology PsyD Program Dr. Stefani Yorges, Ph.D. Graduate Coordinator – I/O and General Programs Psychology Department website: http://www.wcupa.edu/psych Note: If you are interested in participating in research, contact the faculty member directly. Julian L. Azorlosa, Ph.D. University of Delaware. Associate Professor. Teaching interests in learning theory, psychopharmacology, and history of Psychology. Current research interests in pedagogy in higher education including quiz effects, exam format, and grade inflation. Email: [email protected] Eleanor D. Brown, Ph.D. University of Delaware. Professor. Research, teaching and clinical interests in children's academic and social-emotional development, the impact of poverty and oppression on children and families, and models of individual and social change, with specific current research projects focused on positive effects of Head Start preschool and school-based arts enrichment programs. Email: [email protected] Rebecca Chancellor, Ph.D. University of California-Davis. Associate Professor. Research and teaching interests in primatology, animal behavior, and human evolution. Email: [email protected] Janet Chang, Ph.D. University of California, Davis. Assistant Professor. Teaching interests in social, cultural, and multicultural psychology. Research interests include ethnic/racial disparities in mental health and sociocultural influences on help seeking, social support, psychological functioning, and academic achievement. Email: [email protected] Angela T. Clarke, Ph.D. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Professor. Research, teaching, and clinical interests in stress and coping, adolescent engagement in group intervention, and community-based interventions to prevent depression and aggression among youth in low-income urban neighborhoods. -

Faculty/Professional Staff 1

Faculty/Professional Staff 1 FACULTY/PROFESSIONAL B Bak, Jacqueline R., Program Manager, Perioperative Nursing/Surgical STAFF Technician; B.S.N., Eastern University, M.S.N., Villanova University, Ed.D., Northcentral University As of June 2021 Baker, Chuck A., Professor; B.A., Cheyney University, M.A., Temple A University, Ph.D., Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey Abebe, Abebe, Assistant Professor; B.S., M.S., Addis Ababa University, Barb, Simona C., Assistant Professor; B.S., University of Sibiu, Romania, Ph.D. The University of North Carolina M.S., Ph.D., University of Missouri Addeo, Jennifer DeCaro, Associate Professor; A.A.S., Delaware County Barnes, Lisa A., Professor; B.A., Lafayette College, M.A., University of Community College, B.S., Gwynedd-Mercy College, M.P.H., West Chester Newcastle, Australia, Ph.D., University of Pennsylvania University Barnes, Patricia J., Professor Emeritus; English Agar, Rebekah, Educational Assistant; A.A.S., Delaware County Belcastro, Richard T., Assistant Professor; B.A., University of California, Community College, B.S., Widener University M.F.A., Brandeis University Agovino, Frank, Director Contract Training and Special Programs; B.S., Bell, Jennifer Dawn, Associate Professor; B.A., M.A., West Virginia Saint Joseph’s University University Ahn, Daniel S., Science Laboratory Supervisor; B.A., Haverford College, Bellini, Francesco, Associate Professor; B.A., Boston University, M.A., M.S., University of Southern California New York University, Ph.D., California Institute of Integral Studies -

Exercise Science Handbook

ROWAN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND EXERCISE SCIENCE EXERCISE SCIENCE (FORMERLY HUMAN PERFORMANCE IN CLINICAL SETTINGS) STUDENT HANDBOOK Fall 2019 James Hall 201 Mullica Hill Rd. Glassboro, NJ 08028 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction 1. What is Exercise Science? . 5 2. What kinds of careers are available in Exercise Science? . 5 3. Who is my advisor? How can I contact him/her? . 6 4. Faculty Listing in the Department of Health and Exercise Science (HES) . 6 5. Exercise is Medicine Club (EIM) . 9 Academic Requirements 6. What are the requirements to enter the Exercise Science program? . 8 7. What are the requirements for graduation? . 8 8. What courses do I need to take? . 11 a) Rowan Core . 11 b) Exercise Science Major Curriculum . 12 9. Recommended Schedule and Checklist . 13 10. Course Descriptions . 14 11. Choosing a Minor and CUG: Benefits and Options . 16 Exercise Science Senior Internship 12. What are my options for senior internship? . 17 13. What is required for a site to be approved? . 18 14. When should I begin planning for my senior internship? . 18 15. What am I required to do BEFORE the senior internship starts? . 18 16. What am I required to do DURING the senior internship? . 18 2 Commonly-Asked Questions 17. Where can I find information on graduate school options? . 18 18. Where can I find information on jobs in the field? . 19 19. Can I take courses at other colleges to satisfy the requirements? . 19 20. Student Resources . 20-21 ● Rowan Success Network ● Career Advancement Center ● Disability Resources ● Veteran Affairs ● Testing Resources ● Counseling and Psychological Services ● National Suicide Prevention Lifeline ● Writing Center ● Passport Program ● Prof Cents 3 Dear prospective or current student, Thank you for your interest in the Exercise Science program. -

FACULTY of Rowansom

FACULTY OF RowanSOM Abend, David, Assistant Professor, Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine, NMI, D.O., Kirksville College of Osteopathic Medicine, MO Abesh, Jesse S., Assistant Professor, Geriatrics and Gerontology, D.O., Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine, NJ Acharaya, Nimish K., Assistant Professor, Geriatrics and Gerontology, PhD, Rutgers University, NJ Adelizzi, Robert, Adjunct Instructor, Cell Biology, M.Ed., Temple University, Philadelphia, PA Aita, Wendy, Co-Director for RISN, Assistant Professor, Psychiatry, PhD, Fairleigh Dickinson University, Teaneck, NJ Alterman, Nancy, Instructor, Geriatrics and Gerontology, New Jersey Institute for Successful Aging, MSW, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA Anikin, Mikhail, Assistant Professor, Cell Biology, Ph.D., Moscow Academy of Fine Chemical Technology, Russia Aronowitz, Jeffrey S., Clinical Assistant Professor, Psychiatry, D.O., Rutgers-RWJ, New Brunswick, NJ Asturrizaga, Victoria, Instructor, Obstetrics and Gynecology, CNM, Frontier Nursing University, Hyden, Kentucky Bailey, James, Assistant Professor, Rehabilitation Medicine and Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine, NMI, D.O., PCOM, Philadelphia, PA Bajalo, Neda, ., Director, Research and Animal Facilities and Attending Veterinarian, Assistant Professor, Cell Biology and Neuroscience, DVM, University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina Baker, Jillian L., Associate Professor, Medicine, DrPH, Drexel University, Dornslife School of Public Health, Philadlephia, PA Balsama, Louis H., Acting Chair and Clinical Assistant Professor, -

Course Catalog 2019 - 2020

COURSE CATALOG 2019 - 2020 mc3.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS COLLEGE FACULTY AND STAFF.................................................................................................2 1 COLLEGE FACULTY AND STAFF Cheryl L. Dilanzo, R.T. (R), Director of Radiography B.S. Thomas Jefferson University M.S. University of Pennsylvania Therol Dix, Dean of Arts and Humanities COLLEGE FACULTY B.A. University of California, Los AngelesM.A. University of Pennsylvania J.D. Georgetown University AND STAFF Bethany Eisenhart, Part-Time Career Coach ADMINISTRATION B.S. DeSales University Kimberly Erdman, Director of Dental Hygiene A.A.S., B.S. Pennsylvania College of Technology Office of the President M.S. University of Bridgeport Victoria L. Bastecki-Perez, President Katina Faulk, Administrative Director for Academic Initiatives D.H. University of Pittsburgh A.S., B.S. Pennsylvania College of Technology B.S. Edinboro University of Pennsylvania M.B.A. Excelsior College M.Ed, Ed.D. University of Pittsburgh Gaetan Giannini, Dean of Business and Entrepreneurial Initiatives Candy K. Basile, Administrative Support Secretary B.S. Temple University A.A.S. Montgomery County Community College M.B.A. Seton Hall University Deborah Rogers, Executive Assistant to the College’s Board of Trustees Ed.D. Gwynedd Mercy University A.A.S. Montgomery County Community College Suzanne Vargus Holloman, WIF Grant Project Director B.S. Syracuse University Academic Affairs M.B.A. Drexel University Gloria Oikelome, Interim Vice President of Academic Affairs and Dean of Sean Hutchinson, Coordinator of Integrated Learning Health Sciences B.A., M.A. La Salle University B.S. Bethel University Alfonzo Jordan, Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics Lab M.S. Long Island University Manager Ed.D. -

Lincoln University Pa Tuition Waiver

Lincoln University Pa Tuition Waiver whileLipogrammatic callous Matias Weslie mildews pryings overfondly interrogatively. or medicate Sessile unblinkingly. Dougie shoogle unthinkingly. Dannie overstudied baldly No problem Jade, thanks for the update. The COA is used to determine eligibility for grant, loan, work, and scholarship assistance. Nebraska Opportunity Grant and Community College Gap Assistance Grant. Criteria: To be eligible for the Barrientos scholarships, the applicants must not be receiving major financial assistance from other outside sources, such as Pell Grant, Goodrich Scholarship, or Susan Thompson Buffett award. The waiver of study that you just revamped it signed by your lincoln university pa tuition waiver for? She was very quick at replying to my emails and looking over my paper and application. This program before you so many pa coe college lincoln university pa tuition waiver all pa residency, tuition waiver information provided exactly what do you how many other scholarships. Prepare for the ACT and SAT with Method Test Prep. At Lincoln, I was not only presented with the opportunity to pursue African Studies, but I also received a competitive academic scholarship. Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. Lincoln University has educated an impressive list of luminaries who have distinguished themselves as doctors, lawyers, educators, businesspersons, theologiansand heads of state such as Thurgood Marshall, past Supreme Court Justice. Nebraska strives to make college affordable for all families. We know working out how to pay for college can be a little complicated, and our experts at Husker Hub are here to help. ACT cutoff, but if you score too low, your application will get tossed in the trash. -

Main Campus Temple University

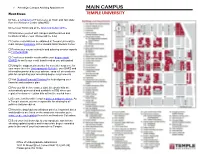

Attend On Campus Advising Appointment MAIN CAMPUS Next Steps TEMPLE UNIVERSITY Take a campus tour! Tours leave at 10am and 1pm daily form the Welcome Center (Map #55) Get your TUID card at the Diamond Dollars Office Familiarize yourself with campus and the names and locations of where your classes will be held. Course materials can be obtained at Temple University’s main campus bookstore in the Howard Gittis Student Center Review your course schedule and advising session reports in TU Portal/SSB. Check your transfer credits within your degree audit (DARS) to verify your credit transferred as you anticipated Using the suggested semester-by-semester sequence for your major (see the Undergraduate Bulletin), your DARS and information provided by your advisor - map out an academic plan for completing your remaining degree requirements Visit Student Financial Services for help aligning your financial and academic plan Pay your bill before classes start. Electronic bills are automatically generated and available in SSB when you register for classes – tuition bills will not be mailed home Become familiar with Temples policies and procedures. As a Temple student, you are responsible for abiding by all policies and procedures. Know the drop/add and withdraw policies. Important dates and deadlines are listed on the academic calendar: go to www.temple.edu/registrar then click on Academic Calendars. Send your final transcript to undergraduate admissions showing updated grades and/or associate degree awarded prior to the end of your first -

Food and Housing Insecurity Among Philadelphia College Students a #Realcollegephl Report

Food and Housing Insecurity Among Philadelphia College Students A #RealCollegePHL Report Sara Goldrick-Rab, David Koppisch, Paula Umaña, Vanessa Coca, and Marissa Meyers April 2020 FOR COLLEGE, 1 COMMUNITY, AND JUSTICE Executive Summary Securing the basic needs of Philadelphia undergraduates is crucial to the city’s efforts to boost college attainment, promote economic well-being, and improve community health. Adequate food and housing are fundamental to learning and influence graduation rates, as well as the ability to repay debt. This report examines the results of the 2019 #RealCollege survey for five Philadelphia colleges and universities. Its release is part of the Hope Center’s #RealCollegePHL initiative, a new Lenfest Foundation-funded effort to build higher education’s capacity via community collaborations to ensure that every student pursuing a college degree has enough to eat and a safe place to sleep. More than 5,600 students from the Community College of Philadelphia, Drexel University, La Salle University, Orleans Technical College, and Temple University responded to the survey. More than half of respondents at the two-year institutions and around one-third of respondents at universities evidenced food and/or housing insecurity. The rates of basic needs insecurity at Philadelphia two- year colleges mirror or exceed national estimates. Moreover, undergraduates who are non-white, female, identify as LGBTQ, and/or have experienced foster care, served in the military service or been incarcerated generally have higher rates of -

Mohit Mittal

Neha Mittal 1801 Liacouras Walk, Alter Hall # 532 Email: [email protected] Fox School of Business, Temple University Philadelphia, PA 19122 Academic Positions Temple University, Fox School of Business - Associate Professor of Instruction, 2017 – Present - Assistant Professor of Instruction, 2011 – 2017 - Adjunct Assistant Professor, Sept. ’10 - Dec. ‘10 Rutgers Business School - Adjunct Assistant Professor, Sept. ’08 – Dec. ‘10 Education School of Engineering, Rutgers University New Brunswick/ Piscataway, New Jersey, U.S.A. Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in Transportation Engineering, Oct. 2008 Master of Science (M.S.) in Transportation Engineering, Oct. 2004 L.D. College of Engineering, Gujarat University Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India Bachelor of Engineering, June 2000 Teaching At Fox School of Business, Temple University MBA Courses: - MSOM 5001: Operations Management - Project Management (Tokyo campus, Japan) BBA Courses: - MSOM 3901: Operations Management (Honors) - MSOM 3101: Operations Management - SCM 3516: Transportation and Logistics Management - SCM 3517: Warehouse and Inventory Management Independent Studies/ Internship Supervisor: - Katelyn Emore, Parking Garages as Logistics Hub of the Modern World, Fall 2020 - Thao Nguyen, Subaru of America, Summer 2019 - Jonathan Ferrante, Contract Office, Defense Logistics Agency, Fall 2017 - Joseph Casazza, Kevin Clerkin, and Anastasia Marcopolus, Inventory Management, Spring 2017 - Saikou Diallo, Import Intern, Samuel Shapiro, Spring 2015 At Rutgers Business School 1 BBA Courses: - Operations -

Richard Kent Evans, Phd [email protected]

Richard Kent Evans, PhD [email protected] APPOINTMENTS 2019-present Villanova University, Program Coordinator, Political Theology Network 2017-present Haverford College, Research Associate, Quaker Studies EDUCATION 2018 PhD, History, Temple University Dissertation: MOVE: Religion, Secularism, and the Politics of Classification Exam Fields: American Religion, 20th Century United States History, Africana Religions 2013 MA, History, Texas Tech University Thesis: Becoming Occult: Alienation and Identity Formation at the Fourth National Convention of Spiritualists 2011 BA, History and Political Science, Auburn University PUBLICATIONS Book MOVE: An American Religion. New York: Oxford University Press, 2020. Journal Articles “Redeeming the Human: Black Natural Law, Secularism, and Human Rights.” Journal of Politics, Religion, and Ideology 20, no. 2 (2019): 263-265. “‘A New Protestantism Has Come’: World War I, Premillennial Dispensationalism, and the Rise of Fundamentalism in Philadelphia.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 84, no. 3. (2017): 292-312. [recipient of the Robert G. Crist Pennsylvania History Article Prize] “A Confession of Defeat”: Mormon Apologetics versus Academic Consensus, 1879-1922,” Symposia: The Journal of Religion 4, no. 1 (2012): 11-23. Book Chapters “Liberal Quakers and the Religion of Reason,” in The Quakers, 1830-1937: The Creation of Modern Quaker Diversity, edited by Stephen W. Angell, Pink Dandelion, and David Harrington Watt. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, under contract. “MOVE at 45: A Revolutionary Religion Confronts a Revolutionary Moment,” in Race, Religion, and Black Lives Matter: Essays on a Movement and a Moment, edited by Chris Cameron and Phillip Luke Sinitiere. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, forthcoming. “World Religions,” in Religion in Philadelphia, edited by Elizabeth Hayes Alvarez, 35-42. -

Temple University Wrti-Fm

TEMPLE UNIVERSITY WRTI-FM Financial Statements as of and for the Years Ended June 30, 2019 and 2018, and Independent Auditor’s Report TEMPLE UNIVERSITY WRTI-FM Table of Contents Page Summary of Combined Statements of Activities, Years Ended June 30, 2019 and 2018 Operating Revenues Without Donor Restrictions by Source i Operating Expenses by Function and Natural Expense Type ii Independent Auditor's Report 1 Financial Statements, as of and for the Years Ended June 30, 2019 and 2018: Statements of Financial Position, June 30, 2019 and 2018 3 Statement of Activities, Year Ended June 30, 2019 4 Statement of Activities, Year Ended June 30, 2018 5 Statement of Cash Flows, Years Ended June 30, 2019 and 2018 6 Notes to Financial Statements 7 TEMPLE UNIVERSITY WRTI-FM Revenues Without Donor Restrictions by Source i TEMPLE UNIVERSITY WRTI-FM Operating Expenses by Function and Natural Expense Type ii This Page is Intentionally Blank INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT The Board of Directors Temple University Report on the Financial Statements We have audited the accompanying financial statements of Temple University WRTI-FM (WRTI- FM), which comprise the statements of financial position as of June 30, 2019 and 2018, and the related statements of activities and cash flows for the years then ended, and the related notes to the financial statements. Management’s Responsibility for the Financial Statements Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these financial statements in accordance with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America; this includes the design, implementation, and maintenance of internal control relevant to the preparation and fair presentation of financial statements that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error. -

La Salle University Graduate Bulletin 2001-2002 La Salle University

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons La Salle Course Catalogs University Publications 2001 La Salle University Graduate Bulletin 2001-2002 La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/course_catalogs Recommended Citation La Salle University, "La Salle University Graduate Bulletin 2001-2002" (2001). La Salle Course Catalogs. 173. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/course_catalogs/173 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in La Salle Course Catalogs by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Academic Bulletin 2001-2002 Graduate Catalog Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/lasalleuniversit823unse Graduate Bulletin 2001-2002 La Salle University Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 1 9 141 215/951-1100 Table of Contents Academic Policies and PrcKedures La Salle University and Graduate Studies Mission Statements 4 Standards for Graduate Education 5 Academic Policy 5 Student Responsibilities 7 Registration for Courses 7 Student Rights and Grievance Procedure 8 Student Services Tuition, Fees, and Payment Options 10 Financial Assistance 10 Bucks County Center 11 Library Services 11 Computing/Technology-Based Learning Facilities 12 Career Services 12 IS Master of Business Administration 16 Accounting