Confucianism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kūnqǔ in Practice: a Case Study

KŪNQǓ IN PRACTICE: A CASE STUDY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THEATRE OCTOBER 2019 By Ju-Hua Wei Dissertation Committee: Elizabeth A. Wichmann-Walczak, Chairperson Lurana Donnels O’Malley Kirstin A. Pauka Cathryn H. Clayton Shana J. Brown Keywords: kunqu, kunju, opera, performance, text, music, creation, practice, Wei Liangfu © 2019, Ju-Hua Wei ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to the individuals who helped me in completion of my dissertation and on my journey of exploring the world of theatre and music: Shén Fúqìng 沈福庆 (1933-2013), for being a thoughtful teacher and a father figure. He taught me the spirit of jīngjù and demonstrated the ultimate fine art of jīngjù music and singing. He was an inspiration to all of us who learned from him. And to his spouse, Zhāng Qìnglán 张庆兰, for her motherly love during my jīngjù research in Nánjīng 南京. Sūn Jiàn’ān 孙建安, for being a great mentor to me, bringing me along on all occasions, introducing me to the production team which initiated the project for my dissertation, attending the kūnqǔ performances in which he was involved, meeting his kūnqǔ expert friends, listening to his music lessons, and more; anything which he thought might benefit my understanding of all aspects of kūnqǔ. I am grateful for all his support and his profound knowledge of kūnqǔ music composition. Wichmann-Walczak, Elizabeth, for her years of endeavor producing jīngjù productions in the US. -

Dai Zhen's Ethical Philosophy of the Human Being

Dai Zhen’s Ethical Philosophy of the Human Being By Ho Young Lee Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of the Study of Religions School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 2006 ProQuest Number: 10672979 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672979 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 Abstract The moral philosophy of Dai Zhen can be summarised as “fulfil desires and express feelings”. Because he believed that life is the most cherished thing for all man and thing, he maintains that “whatever issues from desire is always for the sake of life and nurture.” He also claimed that “caring for oneself, and extending this care to those close to oneself, are both aspects of humanity" He set up a strong monastic moral philosophy based on individual human desire and feeling. As the title ‘Dai Zhen’s philosophy of the ethical human being’ demonstrate, human physical body and activities of life is ethical base of philosophy of Dai Zhen. -

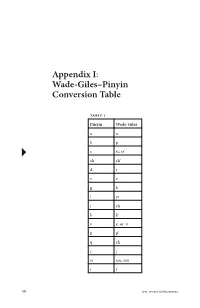

Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table

Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table Table 1 Pinyin Wade-Giles aa bp c ts’, tz’ ch ch’ dt ee gk iyi jch kk’ oe or o pp’ qch rj si ssu, szu tt’ 58 DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table 59 xhs yi i yu u, yu you yu z ts, tz zh ch zi tzu -i (zhi) -ih (chih) -ie (lie) -ieh (lieh) -r (er) rh (erh) Examples jiang chiang zhiang ch’iang zi tzu zhi chih cai tsai Zhu Xi Chu Hsi Xunzi Hsün Tzu qing ch’ing xue hsüeh DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 60 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table Table 2 Wade–Giles Pinyin aa ch’ ch ch j ch q ch zh ee e or oo ff hh hs x iyi -ieh (lieh) -ie (lie) -ih (chih) -i (zhi) jr kg k’ k pb p’ p rh (erh) -r (er) ssu, szu si td t’ t ts’, tz’ c ts, tz z tzu zi u, yu u yu you DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table 61 Examples chiang jiang ch’iang zhiang ch‘ing qing chih zhi Chu Hsi Zhu Xi hsüeh xue Hsün Tzu Xunzi tsai cai tzu zi DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix II: Concordance of Key Philosophical Terms ⠅ai (To love) 1.5, 1.6, 3.17, 12.10, 12.22, 14.7, 17.4, 17.21 (9) 䘧 dao (Way, Path, Road, The Way, To tread a path, To speak, Doctrines, etc.) 1.2, 1.5, 1.11, 1.12, 1.14, 1.15, 2.3, 3.16, 3.24, 4.5, 4.8, 4.9, 4.15, 4.20, 5.2, 5.7, 5.13, 5.16, 5.21, 6.12, 6.17, 6.24, 7.6, 8.4, 8.7, 8.13, 9.12, 9.27, 9.30, 11.20, 11.24, 12.19, 12.23, 13.25, 14.1, 14.3, 14.19, 14.28, 14.36, 15.7, 15.25, 15.29, 15.32, 15.40, 15.42, 16.2, 16.5, 16.11, 17.4, 17.14, 18.2, 18.5, 18.7, 19.2, 19.4, 19.7, 19.12, 19.19, 19.22, 19.25. -

China's Smiling Face to the World: Beijing's English

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CHINA’S SMILING FACE TO THE WORLD: BEIJING’S ENGLISH-LANGUAGE MAGAZINES IN THE FIRST DECADE OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC Leonard W. Lazarick, M.A. History Directed By: Professor James Z. Gao Department of History In the 1950s, the People’s Republic of China produced several English-language magazines to inform the outside world of the remarkable transformation of newly reunified China into a modern and communist state: People’s China, begun in January 1950; China Reconstructs, starting in January 1952; and in March 1958, Peking Review replaced People’s China. The magazines were produced by small staffs of Western- educated Chinese and a few experienced foreign journalists. The first two magazines in particular were designed to show the happy, smiling face of a new and better China to an audience of foreign sympathizers, journalists, academics and officials who had little other information about the country after most Western journalists and diplomats had been expelled. This thesis describes how the magazines were organized, discusses key staff members, and analyzes the significance of their coverage of social and cultural issues in the crucial early years of the People’s Republic. CHINA’S SMILING FACE TO THE WORLD: BEIJING’S ENGLISH-LANGUAGE MAGAZINES IN THE FIRST DECADE OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC By Leonard W. Lazarick Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2005 Advisory Committee: Professor James Z. Gao, Chair Professor Andrea Goldman Professor Lisa R. -

Stony Brook University

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... The Making of National Women: Gender, Nationalism and Social Mobilization in China’s Anti-Japanese War of Resistance, 1937-45 A Dissertation Presented by Dewen Zhang to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University December 2013 Copyright by Dewen Zhang 2013 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Dewen Zhang We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Iona Man-Cheong – Dissertation Advisor Associate Professor, Department of History Nancy Tomes - Chairperson of Defense Professor, Department of History Victoria Hesford Assistant Professor, Department of Cultural Analysis and Theory Danke Li Professor, Department of History Fairfield University This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation The Making of National Women: Gender, Nationalism and Social Mobilization in China’s Anti-Japanese War of Resistance, 1937-45 by Dewen Zhang Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University 2013 Drawing on materials from the Second Historical Archive of China, the Rockefeller Archive Center, the Special Collection of American Bureau for Medical Aid to China, as well as other published and unpublished materials gathered in mainland China, Taiwan and the U.S., this dissertation discusses a broad spectrum of women of various social and political affiliations performed a wide range of work to mobilize collective resistance against Japanese aggression. -

East Asian Studies Undergraduate Course List for 2013-2014

EAST ASIAN STUDIES UNDERGRADUATE COURSE LIST FOR 2013-2014 CEAS Provisional Course Listing as of August 23rd, 2013 Some of the information contained here may have changed since the time of publication. Always check with the department under which the course is listed, or on the Official Yale Online Course Information website found at www.yale.edu/courseinfo to see whether the courses you are interested in are still being offered and that the times have not changed. Please note that course numbers listed with an "a" are offered in the 2013 fall term and those with a "b" are offered in the 2014 spring term. Courses with a ** satisfy the pre-modern requirement for the East Asian Studies major. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ANTHROPOLOGY ANTH 170a Chinese Culture, Society, and History Helen Siu MWF 9.25-10.15 Anthropological explorations of basic institutions in traditional and contemporary Chinese society. Topics include kinship and marriage, religion and ritual, economy and social stratification, state culture, socialist revolution, and market reform. ANTH 234a/WGSS 234a Disability and Culture Karen Nakamura MW 11.35-12.50 Exploration of disability from a cross-cultural perspective, using examples from around the globe. Disability as it relates to identity, culture, law, and politics. Case studies may include deafness in Japan, wheelchair mobility in the United States, and mental illness in the former Soviet republics. ANTH 254b Japan: Culture, Society, Modernity Karen Nakamura MW 1.00-2.50 Introduction to Japanese society and culture. The historical development of Japanese society; family, work, and education in contemporary Japan; Japanese aesthetics; and psychological, sociological, and cultural interpretations of Japanese behavior. -

University at Buffalo Confucius Institute Event Listing 2009 to the Present in Reverse Chronological Order

UNIVERSITY AT BUFFALO CONFUCIUS INSTITUTE EVENT LISTING 2009 TO THE PRESENT IN REVERSE CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER 2021 COVID 19: HUMAN RIGHTS AND INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION April 30, 8:30-3:00PM 2021 Alison Des Forges International Virtual Symposium, cosponsored by the Confucius Institute THE URBANIZATION OF PEOPLE: DEVELOPMENT, LABOR MARKETS AND SCHOOLING IN THE CHINESE CITY April 23, 12:30-1:30PM Zoom presentation by Eli Friedman, Associate Professor of International and Comparative Labor, ILR School, Cornell University Cosponsored by the UB Graduate School of Education UB CONFUCIUS INSTITUTE / DISTINGUISHED ARCHITECTURE LECTURE April 21, 6:00-7:30PM Zoom presentation by Tiantian Xu, Founding Principal, DnA_Design and Architecture, Beijing Part of the UB School of Architecture and Planning 2020-21 “Toward Racial Justice” lecture series COLLABORATING TO PROVIDE EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES FOR CHILDREN WITH AUTISM IN CHINA April 1, 12:30-1:30PM Zoom presentation by Helen McCabe, Associate Professor of Education, Daemen College, and Executive Director of The Five Project U.S.-CHINA THIRD SPACE: STORY CIRCLE WORKSHOP FOR HIGH SCHOOL TEACHERS February 27, 1-2:30PM, with follow up session on March 2, 7:30-8:30PM Presented by Frank Dolce, PhD, for U.S.-China Heartland Association and the St. Cloud State University Confucius Institute FAMINE AND MARITAL ASSORTATIVE MATCHING: EVIDENCE FROM CHINA February 25, 9:30-11:00AM Zoom presentation by Yiru Wang, Assistant Professor of Economics, Southwest University of Finance and Economics (Chengdu) Cosponsored by the UB Department of Economics CELEBRATION OF THE YEAR OF THE OX WITH THE GREAT LAKES CHINESE CONSORTIUM February 13 Online program cohosted with the Confucius Institute at St. -

Yale and China: Yale and China: at a Glance at a Glance

SUMMARY OF YALE UNIVERSITY’S SUMMARY OF YALE UNIVERSITY’S COLLABORATIONS AND HISTORY WITH CHINA COLLABORATIONS AND HISTORY WITH CHINA Yale University has had a longer and deeper relationship with China than any other university in Yale University has had a longer and deeper relationship with China than any other university in the West. Its ties to China date to 1835 when Yale graduate Peter Parker opened China’s first the West. Its ties to China date to 1835 when Yale graduate Peter Parker opened China’s first Western-style hospital in Guangzhou. His papers and medical illustrations sparked the interest Western-style hospital in Guangzhou. His papers and medical illustrations sparked the interest of Yale’s students and faculty in China. Recruited by Parker, Yung Wing (sometimes known as of Yale’s students and faculty in China. Recruited by Parker, Yung Wing (sometimes known as Rong Hong), became the first person from China to earn a degree from an American university Rong Hong), became the first person from China to earn a degree from an American university when he graduated from Yale in 1854. In turn, he helped pave the way to Yale for other Chinese when he graduated from Yale in 1854. In turn, he helped pave the way to Yale for other Chinese students who subsequently played major roles in China. students who subsequently played major roles in China. This unique relationship has grown dramatically stronger over the years through joint This unique relationship has grown dramatically stronger over the years through joint educational and research projects, student and faculty exchange programs, and an ever- educational and research projects, student and faculty exchange programs, and an ever- increasing number of Chinese students and scholars at Yale. -

Asian Philosophy Vol. 11, No. 1

APA Newsletters NEWSLETTER ON ASIAN AND ASIAN-AMERICAN PHILOSOPHERS AND PHILOSOPHY Volume 11, Number 1 Fall 2011 FROM THE EDITOR, DAVID H. KIM ARTICLES A. MINH NGUYEN “Teaching Chinese Philosophy: A Survey of the Field” FALGUNI A. SHETH “Report on ‘(Mis)Recognition: Race, Emotion, Embodiment’ Panel” © 2011 by The American Philosophical Association ISSN 2155-9708 APA NEWSLETTER ON Asian and Asian-American Philosophers and Philosophies David H. Kim, Editor Fall 2011 Volume 11, Number 1 on this philosophical tradition in progress (with Professor Bang FROM THE EDITOR at Kyungpook National University, South Korea) and translating Chong, Yak-Yong (丁若鏞)’s “Four Commentaries on Yi-Jing” (周易四箋) (also with Professor Bang). JeeLoo Liu is Associate Professor of Philosophy at David H. Kim CSU Fullerton and President of the Association of Chinese University of San Francisco Philosophers in America (ACPA). Her research interests are Chinese Philosophy and Philosophy of Mind. She is the author of The value of Chinese Philosophy—not to mention Asian An Introduction to Chinese Philosophy: From Ancient Philosophy Philosophy generally—warrants much greater recognition in the to Chinese Buddhism (Blackwell, 2006) and co-editor, with profession than it currently receives. The teaching of Chinese John Perry, of Consciousness and the Self (Cambridge philosophy, then, is a significant matter, and this edition of the University Press, December 2011). Currently, she is working Newsletter begins with an important service to the profession, on a monograph on Neo-Confucianism, tentatively entitled a survey article by Professor Minh Nguyen on current teaching Metaphysics, Morality, and Mind: An Analytic Reconstruction of Chinese Philosophy in various parts of the world and in of Neo-Confucianism. -

A Wretched Idealist”: Tragedy in “Love Must Not Be Forgotten” Daijuan Gao [email protected]

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs) Spring 5-15-2016 “A Wretched Idealist”: Tragedy in “Love Must Not Be Forgotten” Daijuan Gao [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gao, Daijuan, "“A Wretched Idealist”: Tragedy in “Love Must Not Be Forgotten”" (2016). Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs). 2182. http://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations/2182 Abstract Since its publication in 1979 and the ensuing controversy it evoked about the morality of an extramarital love affair (albeit platonic), Zhang Jie’s short story, “Love Must Not Be Forgotten” has continued to captivate readers and literary scholars. While the values of Zhang’s story, with its challenges to traditional ethics and its provocation of female consciousness, have been acknowledged by critics and commentators, examination of the aesthetics of the story’s tragic effect has thus far remained marginal. “Love” engendered pity and fear in readers, particularly during the time following the Cultural Revolution when the lives of Chinese people were firmly constrained by both established conventions and Communist ideology. It especially resonated with people who were miserable in their loveless marriages as it had provided them with a script of their own stories. The root of the tragedy in “Love” is multifaceted. While Zhong Yu’s unwavering Romantic ideals, the cadre’s “hamartia” (marrying his wife out of a sense of duty), and the confinement of society’s orthodox values all contribute to the tragic affair, chance and destiny also play a pivotal role in the characters’ lives. -

Confucius” (2010)

From Philosopher to Cultural Icon: Reflections on Hu M ei’s “Confucius” (2010) Joseph Tse-Hei Lee, Ronald K. Frank, Renqiu Yu, and Bing Xu Occasional Paper No. 11 M arch 2011 Centre for Qualitative Social Research Center for East Asian Studies Department of Sociology Department of History Hong Kong Shue Yan University Pace University Hong Kong SAR, China New York, USA From Philosopher to Cultural Icon: Ref lections on Hu M ei’s “Confucius” (2010) Joseph Tse-Hei Lee, Ronald K. Frank, Renqiu Yu, and Bing Xu Social and Cultural Research Occasional Paper Series Social and Cultural Research is an occasional paper series that prom otes the interdisciplinary study of social and historical change in Hong Kong, China and other parts of Asia. The appearance of papers in this series does not preclude later publication in revised version in an academ ic journal or book. Editors Siu-Keung CHEUNG Joseph Tse-Hei LEE Centre for Qualitative Social Research Center for East Asian Studies Departm ent of Sociology Departm ent of History Hong Kong Shue Yan University Pace University Email: [email protected] Em ail: [email protected] Harold TRAVER Ronald K. FRANK Centre for Qualitative Social Research Center for East Asian Studies Departm ent of Sociology Departm ent of History Hong Kong Shue Yan University Pace University Em ail: [email protected] Em ail: [email protected] Published and distributed by Centre for Qualitative Social Research Center for East Asian Studies Departm ent of Sociology Departm ent of History Hong Kong Shue Yan University Pace University 10 W ai Tsui Crescent, Braemar Hill 1 Pace Plaza North Point, Hong Kong SAR, China New York, 10038, USA Tel: (852) 2570 7110 Tel: (1) 212-3461827 Email: [email protected] Em ail: [email protected] ISSN 1996-6784 Printed in Hong Kong Copyright of each paper rests with its author(s). -

The Macmillan Center for International and Area Studies at Editor: David J

September 10, 2006 ale university 2007 – Number 15 bulletin of y Series 102 The MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies 2006 bulletin of yale university September 10, 2006 MacMillan Center Periodicals postage paid New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8227 ct bulletin of yale university bulletin of yale New Haven Bulletin of Yale University The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and affirmatively seeks to attract Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, to its faculty, staff, and student body qualified persons of diverse backgrounds. In accordance with PO Box 208227, New Haven ct 06520-8227 this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admis- sions, educational programs, or employment against any individual on account of that individual’s PO Box 208230, New Haven ct 06520-8230 Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, status as a special disabled veteran, veteran of the Vietnam era, or other covered veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis Issued seventeen times a year: one time a year in May, November, and December; two times of sexual orientation. a year in June; three times a year in July and September; six times a year in August University policy is committed to affirmative action under law in employment of women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, special disabled veterans, veterans of the Managing Editor: Linda Koch Lorimer Vietnam era, and other covered veterans.