Xenophobia, Radicalism, and Hate Crime in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MINOR POLITICAL PARTIES and the LANGUAGE of POLITICS in LATE COLONIAL BENGAL(L921-194?); ATTITUDE, ADJUSTMENT and REACTION

MINOR POLITICAL PARTIES AND THE LANGUAGE OF POLITICS IN LATE COLONIAL BENGAL(l921-194?); ATTITUDE, ADJUSTMENT AND REACTION THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL BY KOUSHIKIDASGUPTA ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF GOUR BANGA MALDA UPERVISOR PROFESSOR I. SARKAR DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL RAJA RAMMOHANPUR, DARJEELING WEST BENGAL 2011 IK 35 229^ I ^ pro 'J"^') 2?557i UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL Raja Rammohunpur P.O. North Bengal University Dist. Darjeeling - 734013 West Bengal (India) • Phone : 0353 - 2776351 Ref. No Date y.hU. CERTIFICATE OF GUIDE AND SUPERVISOR Certified that the Ph.D. thesis prepared by Koushiki Dasgupta on Minor Political Parties and the Language of Politics in Late Colonial Bengal ^921-194'^ J Attitude, Adjustment and Reaction embodies the result of her original study and investigation under my supervision. To the best of my knowledge and belief, this study is the first of its kind and is in no way a reproduction of any other research work. Dr.LSarkar ^''^ Professor of History Department of History University of North Bengal Darje^ingy^A^iCst^^a^r Department of History University nfVi,rth Bengal Darjeeliny l\V Bj DECLARATION I do hereby declare that the thesis entitled MINOR POLITICAL PARTIES AND THE LANGUAGE OF POLITICS IN LATE COLONIAL BENGAL (l921- 1947); ATTITUDE, ADJUSTMENT AND REACTION being submitted to the University of North Bengal in partial fulfillment for the award of Doctor of Philosophy in History is an original piece of research work done by me and has not been published or submitted elsewhere for any other degree in full or part of it. -

Historical Traumas in Post-War Hungary: Legacies and Representations of Genocide and Dictatorship

The Hungarian Historical Review New Series of Acta Historica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae Volume 6 No. 2 2017 Historical Traumas in Post-War Hungary: Legacies and Representations of Genocide and Dictatorship Balázs Apor Special Editor of the Thematic Issue Contents Articles Zsolt Győri Discursive (De)Constructions of the Depoliticized Private Sphere in The Resolution and Balaton Retro 271 tamás BeZsenyi and The Legacy of World War II and Belated Justice andrás lénárt in the Hungarian Films of the Early Kádár Era 300 Péter Fodor Erasing, Rewriting, and Propaganda in the Hungarian Sports Films of the 1950s 328 anna menyhért Digital Trauma Processing in Social Media Groups: Transgenerational Holocaust Trauma on Facebook 355 ZsóFia réti Past Traumas and Future Generations: Cultural Memory Transmission in Hungarian Sites of Memory 377 lóránt Bódi The Documents of a Fresh Start in Life: Marriage Advertisements Published in the Israelite Newspaper Új Élet (New Life) Between 1945–1952 404 http://www.hunghist.org HHR_2017-2.indb 1 9/26/2017 3:20:01 PM Contents Featured review The Routledge History of East Central Europe since 1700. Edited by Irina Livezeanu and Árpád von Klimó. Reviewed by Ferenc Laczó 427 Book reviews Central Europe in the High Middle Ages: Bohemia, Hungary and Poland, c. 900–c. 1300. By Nora Berend, Przemysław Urbańczyk, and Przemysław Wiszewski. Reviewed by Sébastien Rossignol 434 Deserting Villages – Emerging Market Towns: Settlement Dynamics and Land Management in the Great Hungarian Plain: 1300–1700. By Edit Sárosi. Reviewed by András Vadas 437 Das Reich als Netzwerk der Fürsten: Politische Strukturen unter dem Doppelkönigtum Friedrichs II. -

Hungarian Studies ^Eviezv Vol

Hungarian Studies ^eviezv Vol. XXV, Nos. 1-2 (Spring-Fall, 1998) Special Volume: Canadian Studies on Hungarians: A Bibliography (Third Supplement) Janos Miska, comp. This special volume contains a bibliography of recent (1995-1998) Canadian publications on Hungary and Hungarians in Canada and else- where. It also offers a guide to archival sources on Hungarian Canadians in Hungary and Canada; a list of Hungarian-Canadian newspapers, jour- nals and other periodicals ever published; as well as biographies of promi- nent Hungarian-Canadian authors, educators, artists, scientists and com- munity leaders. The volume is completed by a detailed index. The Hungarian Studies Review is a semi- annual interdisciplinary journal devoted to the EDITORS publication of articles and book reviews relat- ing to Hungary and Hungarians. The Review George Bisztray is a forum for the scholarly discussion and University of Toronto analysis of issues in Hungarian history, politics and cultural affairs. It is co-published by the N.F. Dreisziger Hungarian Studies Association of Canada and Royal Military College the National Sz£ch6nyi Library of Hungary. Institutional subscriptions to the HSR are EDITORIAL ADVISERS $12.00 per annum. Membership fees in the Hungarian Studies Association of Canada in- Oliver Botar clude a subscription to the journal. University of Manitoba For more information, visit our web-page: Geza Jeszenszky http://www.ccsp.sfu.ca/calj.hsr Budapest- Washington Correspondence should be addressed to: Ilona Kovacs National Szechenyi Library The Editors, Hungarian Studies Review, University of Toronto, Mlria H. Krisztinkovich 21 Sussex Ave., Vancouver Toronto, Ont., Canada M5S 1A1 Barnabas A. Racz Statements and opinions expressed in the HSR Eastern Michigan U. -

The City of Moscow in Russia's Foreign and Security Policy: Role

Eidgenössische “Regionalization of Russian Foreign and Security Policy” Technische Hochschule Zürich Project organized by The Russian Study Group at the Center for Security Studies and Conflict Research Andreas Wenger, Jeronim Perovic,´ Andrei Makarychev, Oleg Alexandrov WORKING PAPER NO.7 APRIL 2001 The City of Moscow in Russia’s Foreign and Security Policy: Role, Aims and Motivations DESIGN : SUSANA PERROTTET RIOS Moscow enjoys an exceptional position among the Russian regions. Due to its huge By Oleg B. Alexandrov economic and financial potential, the city of Moscow largely shapes the country’s economic and political processes. This study provides an overall insight into the complex international network that the city of Moscow is tied into. It also assesses the role, aims and motivations of the main regional actors that are involved. These include the political authorities, the media tycoons and the major financial-industrial groups. Special attention is paid to the problem of institutional and non-institutional interaction between the Moscow city authorities and the federal center in the foreign and security policy sector, with an emphasis on the impact of Putin’s federal reforms. Contact: Center for Security Studies and Conflict Research ETH Zentrum / SEI CH-8092 Zürich Switzerland Andreas Wenger, head of project [email protected] Jeronim Perovic´ , project coordinator [email protected] Oleg Alexandrov [email protected]; [email protected] Andrei Makarychev [email protected]; [email protected] Order of copies: Center for Security Studies and Conflict Research ETH Zentrum / SEI CH-8092 Zürich Switzerland [email protected] Papers available in full-text format at: http://www.fsk.ethz.ch/ Layout by Marco Zanoli The City of Moscow in Russia’s Foreign and Security Policy: Role, Aims and Motivations By Oleg B. -

Minutes of the 2020 SBI Telco Meeting Recommendations For

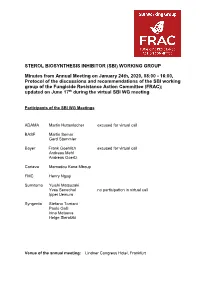

STEROL BIOSYNTHESIS INHIBITOR (SBI) WORKING GROUP Minutes from Annual Meeting on January 24th, 2020, 08:00 - 16:00, Protocol of the discussions and recommendations of the SBI working group of the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC); updated on June 17th during the virtual SBI WG meeting Participants of the SBI WG Meetings ADAMA Martin Huttenlocher excused for virtual call BASF Martin Semar Gerd Stammler Bayer Frank Goehlich excused for virtual call Andreas Mehl Andreas Goertz Corteva Mamadou Kane Mboup FMC Henry Ngugi Sumitomo Yuichi Matsuzaki Yves Senechal no participation in virtual call Ippei Uemura Syngenta Stefano Torriani Paolo Galli Irina Metaeva Helge Sierotzki Venue of the annual meeting: Lindner Congress Hotel, Frankfurt Hosting organization: FRAC/Crop Life International Disclaimer The technical information contained in the global guidelines/the website/the publication/the minutes is provided to CropLife International/RAC members, non- members, the scientific community and a broader public audience. While CropLife International and the RACs make every effort to present accurate and reliable information in the guidelines, CropLife International and the RACs do not guarantee the accuracy, completeness, efficacy, timeliness, or correct sequencing of such information. CropLife International and the RACs assume no responsibility for consequences resulting from the use of their information, or in any respect for the content of such information, including but not limited to errors or omissions, the accuracy or reasonableness of factual or scientific assumptions, studies or conclusions. Inclusion of active ingredients and products on the RAC Code Lists is based on scientific evaluation of their modes of action; it does not provide any kind of testimonial for the use of a product or a judgment on efficacy. -

Ildikó Barna, Bulcsú Hunyadi, Patrik Szicherle and Farah Rasmi Report

Ildikó Barna, Bulcsú Hunyadi, Patrik Szicherle and Farah Rasmi Report on Xenophobia, Radicalism and Hate Crime in Hungary in 2017 Table of Contents 1. CHANGES IN LEGISLATION AFFECTING THE INTERESTS OF MINORITIES IN 2017 ........................................... 4 LEGISLATIVE AMENDMENTS CONCERNING THE ROMA POPULATION ............................................................................ 4 2. LAW ENFORCEMENT PRACTICES AFFECTING MINORITIES IN 2017 ................................................................ 6 DISCRIMINATORY PRACTICES AGAINST THE ROMA ................................................................................................. 6 DECISIONS OF COURTS AND STATE AUTHORITIES REGARDING DISCRIMINATION AGAINST THE ROMA AND OTHER MINORITIES ..... 9 3. THE POSITION OF IMMIGRANTS IN HUNGARY IN 2017 ............................................................................... 12 LEGISLATIVE AMENDMENTS CONCERNING ASYLUM-SEEKERS ................................................................................... 12 LOCAL SELF-GOVERNMENT DECREES ON MIGRATION ............................................................................................ 14 DISCRIMINATORY PRACTICES AGAINST ASYLUM-SEEKERS ....................................................................................... 16 DECISIONS OF COURTS AND STATE AUTHORITIES REGARDING DISCRIMINATION AGAINST ASYLUM-SEEKERS ......................... 19 SOCIAL SUPPORT AVAILABLE FOR IMMIGRANTS .................................................................................................. -

New Parties in the Netherlands Andre´Krouwela and Paul Lucardieb Adepartment of Political Science, Free University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Acta Politica, 2008, 43, (278–307) r 2008 Palgrave Macmillan Ltd 0001-6810/08 $30.00 www.palgrave-journals.com/ap Waiting in the Wings: New Parties in the Netherlands Andre´Krouwela and Paul Lucardieb aDepartment of Political Science, Free University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands. E-mail: [email protected] bDocumentation Centre Dutch Political Parties, University of Groningen, the Netherlands. E-mail: [email protected] Even in the relatively open political system of the Netherlands, most new parties never pass the threshold of representation and keep waiting in vain in the wings of political power. Since 1989 only 10 out of 63 newcomers gained one or more seats in parliament, owing to a favourable political opportunity structure and significant resources. Three of them disappeared into political oblivion after one parliamen- tary term. Only two of them have participated in government. In this paper we offer some explanations as regards the variety in origins as well as a typology with respect to their differences in terms of ideology and policy agenda. The analysis shows that however short-lived parties in opposition may be they have an impact on the political agenda, in particular recently. Acta Politica (2008) 43, 278–307. doi:10.1057/ap.2008.9 Keywords: political parties; new parties; party formation; party origin Introduction: Why Study New Parties? Success sells better than failure. New parties receive therefore scant attention from political scientists as long as they remain marginal and fail to win seats in parliament. Yet, new parties waiting in the wings of the political system may maintain the pristine purity of political principles and ideas better than their established rivals in parliament, let alone parties in government. -

Chapter IV Minor Political Parties and Bengal Politics: 1939-1947

Chapter IV Minor Political Parties and Bengal Politics: 1939-1947 The final debacle of the leftists in the Tripuri session of the Congress of 1939 was resulted in the formation of a Left Consolidation Committee bv Subhas Bose for the purpose of bringing together the quarreling factions of the lefts. The committee set the ground for the unification of the entire radical anti imperialist elements on the basis of a minimum programme. The CSP, the CPI and the Royists apparently showed their eagerness to work with the Left Consolidation Committee but stood against the idea of joining the proposed new party of Subhas Chandra Bose. After his formal resignation from the Congress Presidentship, he declared the formation of Forward Block on 3rd May, 1939 as a left platform within the Congress at a public meeting in Calcutta.^ Among its three major objectives the idea of consolidating the leftist forces or launching an uncompromising struggle against the British had carried with it a direct appeal to the masses as well as to the other left parties.^ But the very objective of wining over the majority section of the Congress indeed opened the scopes for further explanation and confusion. In fact the leftist forces in 1939 had a numbers of reasons to defend their own position and the platform of left consolidation broke up under pressures from different angles. On one point all most all the important forces agreed with the other that in no circumstances they would join the Forward Block and if possible organize their own independent party." In case of the CPI, the situation was a bit tricky because of their general sympathy for the line of United Front which did not allow them to take a reactionary stand against 256 the rightists under Gandhi ^. -

Download Download

Religion and the Development of the Dutch Trade Union Movement, 1872-1914 by Erik HANSEN and Peter A. PROSPER, Jr.* In a recently published essay, ''Segmented Pluralism : Ideological Cleavages and Political Cohesion in the Smaller European Democracies," Val Lorwin examines the process whereby separate and distinct ideolog ical and religious groupings in Austria, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Switzerland have been able to accommodate each other and to evolve into stable, capitalist, parliamentary democracies in the post-World War 1 II era. • As a point of departure, Lorwin draws a sharp distinction be tweenfunctional groupings and those which are segmented. A trade union which bargains on behalf of Austri,.m metal workers is a functional asso ciation. However, a Roman Catholic metal workers union is segmented in that its Roman Catholic attribute carries with it something more than a purely socio-economic role. A segmented plural society is thus a group ing of ideological blocs, be they religious, liberal, or to one degree or another socialist. The blocs may be defined in terms of class and thus the labour or socialist groupings in Austria, Belgium, and the Netherlands with their respective liberal bourgeois counterparts, or they may be reli gious blocs such as the Roman Catholic communities in Austria, Belgium and the Netherlands or the Protestant churches in the Netherlands. A society in which these blocs maintain separate but parallel political parties, newspapers, various types of voluntary associations, e.g., women's leagues, youth clubs, athletic facilities and competition, trade unions and, in some instances, school systems, Lorwin terms segmented and pluralist. -

Criminal Geographical Journal February 2021 CRIMINAL GEOGRAPHICAL JOURNAL

2021 1-2. Criminal Geographical Journal February 2021 _ CRIMINAL GEOGRAPHICAL JOURNAL Number 1-2 Volume III. February 2021 ISSN 2676-9778 GÁBOR ANDROVICZ: Service placement and housing conditions of the Budapest police staff from the 1880s to the 1930s SZABOLCS MÁTYÁS – ZSOLT LIPPAI – ÁGOTA NÉMETH – PÉTER FELFÖLDI – IVETT NAGY – ERIKA GÁL: Criminal geographical analysis of cycling accidents in Budapest ANDREA PŐDÖR: Investigation of different visualisation methods for crime mapping MÁTÉ SIVADÓ: The basic patterns of drug use are in some parts of the world and the possible causes of differences Abstracts of the 1st Criminal Geography Conference of the Hungarian Assocation of Police Science Hungarian Association of Police Science 1 Criminal Geographical Journal February 2021 CGJ ___________________________________________________________________________ CRIMINAL GEOGRAPHICAL JOURNAL ___________________________________________________________________________ ACADEMIC AND APPLIED RESEARC IN CRIMINAL GEOGRAPHY SCIENCE VOLUME III / NUMBER 1-2 / FEBRUARY 2021 2 Criminal Geographical Journal February 2021 Academic and applied research in criminal geography science. CGR is a peer-reviewed international scientific journal. Published four times a year. Chairman of the editorial board: SZABOLCS MÁTYÁS Ph.D. assistant professor (University of Public Service, Hungary) Honorary chairman of the editorial board: JÁNOS SALLAI Ph.D. professor (University of Public Service, Hungary) Editor in chief: VINCE VÁRI Ph.D. assistant professor (University of Public Service, Hungary) Editorial board: UFUK AYHAN Ph.D. associate professor (Turkish National Police Academy, Turkey) MARJAN GJUROVSKI Ph.D. assistant professor (State University ’St. Kliment Ohridski’, Macedonia) LADISLAV IGENYES Ph.D. assistant professor (Academy of the Police Force in Bratislava, Slovakia) IVAN M. KLEYMENOV Ph.D. professor (National Research University Higher School of Economics, Russia) KRISTINA A. -

Government Documents Index by Title

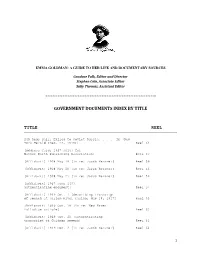

EMMA GOLDMAN: A GUIDE TO HER LIFE AND DOCUMENTARY SOURCES Candace Falk, Editor and Director Stephen Cole, Associate Editor Sally Thomas, Assistant Editor GOVERNMENT DOCUMENTS INDEX BY TITLE TITLE REEL 249 Reds Sail, Exiled to Soviet Russia. In [New York Herald (Dec. 22, 1919)] Reel 64 [Address Card, 1917 July? for Mother Earth Publishing Association] Reel 57 [Affidavit] 1908 May 18 [in re: Jacob Kersner] Reel 56 [Affidavit] 1908 May 20 [in re: Jacob Kersner] Reel 56 [Affidavit] 1908 May 21 [in re: Jacob Kersner] Reel 56 [Affidavit] 1917 June 1[0? authenticating document] Reel 57 [Affidavit] 1919 Oct. 1 [describing transcript of speech at Harlem River Casino, May 18, 1917] Reel 63 [Affidavit] 1919 Oct. 18 [in re: New Haven Palladium article] Reel 63 [Affidavit] 1919 Oct. 20 [authenticating transcript of Goldman speech] Reel 63 [Affidavit] 1919 Dec. 2 [in re: Jacob Kersner] Reel 64 1 [Affidavit] 1920 Feb. 5 [in re: Abraham Schneider] Reel 65 [Affidavit] 1923 March 23 [giving Emma Goldman's birth date] Reel 65 [Affidavit] 1933 Dec. 26 [in support of motion for readmission to United States] Reel 66 [Affidavit? 1917? July? regarding California indictment of Alexander Berkman (excerpt?)] Reel 57 Affirms Sentence on Emma Goldman. In [New York Times (Jan. 15, 1918)] Reel 60 Against Draft Obstructors. In [Baltimore Sun (Jan. 15, 1918)] Reel 60 [Agent Report] In re: A.P. Olson (or Olsson)-- Anarchist and Radical, New York, 1918 Aug. 30 Reel 61 [Agent Report] In re: Abraham Schneider--I.W.W., St. Louis, Mo. [19]19 Oct. 14 Reel 63 [Agent Report In re:] Abraham Schneider, St. -

Outgoing Chancellor Sebastian Kurz's People's Party (ÖVP) Favourite in the Snap Election in Austria on 29Th September Next

GENERAL ELECTION IN AUSTRIA 29th September 2019 European Outgoing Chancellor Sebastian Elections Monitor Kurz’s People’s Party (ÖVP) favourite in the snap election in Corinne Deloy Austria on 29th September next Analysis 6.4 million Austrians aged at least 16 are being called leadership of the FPÖ. He was replaced by Norbert Hofer, to ballot on 29th September to elect the 183 members Transport Minister and the unlucky candidate in the last of the National Council (Nationalrat), the lower house presidential election in 2016, when he won 48.3% of the of Parliament. This election, which is being held three vote and was beaten by Alexander Van der Bellen (51.7%) years ahead of schedule, follows the dismissal of the in the second round of the election on 4th December. government chaired by Chancellor Kurz (People’s Party, ÖVP) by the National Council on 27th May last. It was the The day after the European elections, Chancellor first time in the country’s history that a government lost Sebastian Kurz was removed from office. On 3rd June, a vote of confidence (103 of the 183 MPs voted against). Brigitte Bierlein, president of the Constitutional Court, It is even more remarkable that on the day before the became the first female Chancellor in Austria’s history. vote regarding his dismissal, the ÖVP easily won the Appointed by the President of the Republic Van der Bellen, European elections on 26th May with 34.55% of the vote. she has ensured the interim as head of government. On 21st June the Austrian authorities announced that a snap This vote of no-confidence followed the broadcast, ten election would take place on 29th September.