New Parties in the Netherlands Andre´Krouwela and Paul Lucardieb Adepartment of Political Science, Free University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MINOR POLITICAL PARTIES and the LANGUAGE of POLITICS in LATE COLONIAL BENGAL(L921-194?); ATTITUDE, ADJUSTMENT and REACTION

MINOR POLITICAL PARTIES AND THE LANGUAGE OF POLITICS IN LATE COLONIAL BENGAL(l921-194?); ATTITUDE, ADJUSTMENT AND REACTION THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL BY KOUSHIKIDASGUPTA ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF GOUR BANGA MALDA UPERVISOR PROFESSOR I. SARKAR DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL RAJA RAMMOHANPUR, DARJEELING WEST BENGAL 2011 IK 35 229^ I ^ pro 'J"^') 2?557i UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL Raja Rammohunpur P.O. North Bengal University Dist. Darjeeling - 734013 West Bengal (India) • Phone : 0353 - 2776351 Ref. No Date y.hU. CERTIFICATE OF GUIDE AND SUPERVISOR Certified that the Ph.D. thesis prepared by Koushiki Dasgupta on Minor Political Parties and the Language of Politics in Late Colonial Bengal ^921-194'^ J Attitude, Adjustment and Reaction embodies the result of her original study and investigation under my supervision. To the best of my knowledge and belief, this study is the first of its kind and is in no way a reproduction of any other research work. Dr.LSarkar ^''^ Professor of History Department of History University of North Bengal Darje^ingy^A^iCst^^a^r Department of History University nfVi,rth Bengal Darjeeliny l\V Bj DECLARATION I do hereby declare that the thesis entitled MINOR POLITICAL PARTIES AND THE LANGUAGE OF POLITICS IN LATE COLONIAL BENGAL (l921- 1947); ATTITUDE, ADJUSTMENT AND REACTION being submitted to the University of North Bengal in partial fulfillment for the award of Doctor of Philosophy in History is an original piece of research work done by me and has not been published or submitted elsewhere for any other degree in full or part of it. -

Gender and Right-Wing Populism in the Low Countries: Ideological Variations Across Parties and Time Sarah L

This article was downloaded by: [Harvard Library] On: 05 March 2015, At: 06:40 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Patterns of Prejudice Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rpop20 Gender and right-wing populism in the Low Countries: ideological variations across parties and time Sarah L. de Lange & Liza M. Mügge Published online: 26 Feb 2015. Click for updates To cite this article: Sarah L. de Lange & Liza M. Mügge (2015): Gender and right-wing populism in the Low Countries: ideological variations across parties and time, Patterns of Prejudice, DOI: 10.1080/0031322X.2015.1014199 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0031322X.2015.1014199 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe by Kimberly Ann Twist a Dissertation Submitted In

The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe by Kimberly Ann Twist A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Jonah D. Levy, Chair Professor Jason Wittenberg Professor Jacob Citrin Professor Katerina Linos Spring 2015 The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe Copyright 2015 by Kimberly Ann Twist Abstract The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe by Kimberly Ann Twist Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Jonah D. Levy, Chair As long as far-right parties { known chiefly for their vehement opposition to immigration { have competed in contemporary Western Europe, scholars and observers have been concerned about these parties' implications for liberal democracy. Many originally believed that far- right parties would fade away due to a lack of voter support and their isolation by mainstream parties. Since 1994, however, far-right parties have been included in 17 governing coalitions across Western Europe. What explains the switch from exclusion to inclusion in Europe, and what drives mainstream-right parties' decisions to include or exclude the far right from coalitions today? My argument is centered on the cost of far-right exclusion, in terms of both office and policy goals for the mainstream right. I argue, first, that the major mainstream parties of Western Europe initially maintained the exclusion of the far right because it was relatively costless: They could govern and achieve policy goals without the far right. -

The Rise of Kremlin-Friendly Populism in the Netherlands

CICERO FOUNDATION GREAT DEBATE PAPER No. 18/04 June 2018 THE RISE OF KREMLIN-FRIENDLY POPULISM IN THE NETHERLANDS MARCEL H. VAN HERPEN Director The Cicero Foundation Cicero Foundation Great Debate Paper No. 18/04 © Marcel H. Van Herpen, 2018. ISBN/EAN 978-90-75759-17-4 All rights reserved The Cicero Foundation is an independent pro-Atlantic and pro-EU think tank, founded in Maastricht in 1992. www.cicerofoundation.org The views expressed in Cicero Foundation Great Debate Papers do not necessarily express the opinion of the Cicero Foundation, but they are considered interesting and thought-provoking enough to be published. Permission to make digital or hard copies of any information contained in these web publications is granted for personal use, without fee and without formal request. Full citation and copyright notice must appear on the first page. Copies may not be made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage. 2 The Rise of Kremlin-Friendly Populism in the Netherlands Marcel H. Van Herpen EARLY POPULISM AND THE MURDERS OF FORTUYN AND VAN GOGH The Netherlands is known as a tolerant and liberal country, where extremist ideas – rightwing or leftwing – don’t have much impact. After the Second World War extreme right or populist parties played only a marginal role in Dutch politics. There were some small fringe movements, such as the Farmers’ Party ( Boerenpartij ), led by the maverick “Boer Koekoek,” which, in 1967, won 7 seats in parliament. In 1981 this party lost its parliamentary representation and another party emerged, the extreme right Center Party ( Centrum Partij ), led by Hans Janmaat. -

Populism in Europe: Netherlands

Demos is a think-tank focused on power and politics. Our unique approach challenges the traditional, 'ivory tower' model of policymaking by giving a voice to people and communities. We work together with the groups and individuals who are the focus of our research, including them in citizens’ juries, deliberative workshops, focus groups and ethnographic research. Through our high quality and socially responsible research, Demos has established itself as the leading independent think-tank in British politics. In 2012, our work is focused on four programmes: Family and Society; Public Services and Welfare; Violence and Extremism; and Citizens. Alongside and connected with our research programes, Demos has political projects focused on the burning issues in current political thinking, including the Progressive Conservatism Project, the Centre for London at Demos and Demos Collections, bringing together topical essays by leading thinkers and commentators. Our work is driven by the goal of a society populated by free, capable, secure and powerful citizens. Find out more at www.demos.co.uk. POPULISM IN EUROPE: NETHERLANDS Jamie Bartlett Jonathan Birdwell Sarah de Lange First published in 2012 © Demos. Some rights reserved Magdalen House, 136 Tooley Street London, SE1 2TU, UK ISBN 978-1-906693-15-1 Copy edited by Susannah Wight Series design by modernactivity Typeset by modernactivity Set in Gotham Rounded and Baskerville 10 Open access. Some rights reserved. As the publisher of this work, Demos wants to encourage the circulation of our work as widely as possible while retaining the copyright. We therefore have an open access policy which enables anyone to access our content online without charge. -

The Conservative Embrace of Progressive Values Oudenampsen, Merijn

Tilburg University The conservative embrace of progressive values Oudenampsen, Merijn Publication date: 2018 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Oudenampsen, M. (2018). The conservative embrace of progressive values: On the intellectual origins of the swing to the right in Dutch politics. [s.n.]. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. sep. 2021 The conservative embrace of progressive values On the intellectual origins of the swing to the right in Dutch politics The conservative embrace of progressive values On the intellectual origins of the swing to the right in Dutch politics PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. E.H.L. Aarts, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de aula van de Universiteit op vrijdag 12 januari 2018 om 10.00 uur door Merijn Oudenampsen geboren op 1 december 1979 te Amsterdam Promotor: Prof. -

Chapter IV Minor Political Parties and Bengal Politics: 1939-1947

Chapter IV Minor Political Parties and Bengal Politics: 1939-1947 The final debacle of the leftists in the Tripuri session of the Congress of 1939 was resulted in the formation of a Left Consolidation Committee bv Subhas Bose for the purpose of bringing together the quarreling factions of the lefts. The committee set the ground for the unification of the entire radical anti imperialist elements on the basis of a minimum programme. The CSP, the CPI and the Royists apparently showed their eagerness to work with the Left Consolidation Committee but stood against the idea of joining the proposed new party of Subhas Chandra Bose. After his formal resignation from the Congress Presidentship, he declared the formation of Forward Block on 3rd May, 1939 as a left platform within the Congress at a public meeting in Calcutta.^ Among its three major objectives the idea of consolidating the leftist forces or launching an uncompromising struggle against the British had carried with it a direct appeal to the masses as well as to the other left parties.^ But the very objective of wining over the majority section of the Congress indeed opened the scopes for further explanation and confusion. In fact the leftist forces in 1939 had a numbers of reasons to defend their own position and the platform of left consolidation broke up under pressures from different angles. On one point all most all the important forces agreed with the other that in no circumstances they would join the Forward Block and if possible organize their own independent party." In case of the CPI, the situation was a bit tricky because of their general sympathy for the line of United Front which did not allow them to take a reactionary stand against 256 the rightists under Gandhi ^. -

Download Download

Religion and the Development of the Dutch Trade Union Movement, 1872-1914 by Erik HANSEN and Peter A. PROSPER, Jr.* In a recently published essay, ''Segmented Pluralism : Ideological Cleavages and Political Cohesion in the Smaller European Democracies," Val Lorwin examines the process whereby separate and distinct ideolog ical and religious groupings in Austria, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Switzerland have been able to accommodate each other and to evolve into stable, capitalist, parliamentary democracies in the post-World War 1 II era. • As a point of departure, Lorwin draws a sharp distinction be tweenfunctional groupings and those which are segmented. A trade union which bargains on behalf of Austri,.m metal workers is a functional asso ciation. However, a Roman Catholic metal workers union is segmented in that its Roman Catholic attribute carries with it something more than a purely socio-economic role. A segmented plural society is thus a group ing of ideological blocs, be they religious, liberal, or to one degree or another socialist. The blocs may be defined in terms of class and thus the labour or socialist groupings in Austria, Belgium, and the Netherlands with their respective liberal bourgeois counterparts, or they may be reli gious blocs such as the Roman Catholic communities in Austria, Belgium and the Netherlands or the Protestant churches in the Netherlands. A society in which these blocs maintain separate but parallel political parties, newspapers, various types of voluntary associations, e.g., women's leagues, youth clubs, athletic facilities and competition, trade unions and, in some instances, school systems, Lorwin terms segmented and pluralist. -

Tilburg University the Conservative

Tilburg University The conservative embrace of progressive values Oudenampsen, Merijn Publication date: 2018 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Oudenampsen, M. (2018). The conservative embrace of progressive values: On the intellectual origins of the swing to the right in Dutch politics. [s.n.]. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. okt. 2021 The conservative embrace of progressive values On the intellectual origins of the swing to the right in Dutch politics The conservative embrace of progressive values On the intellectual origins of the swing to the right in Dutch politics PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. E.H.L. Aarts, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de aula van de Universiteit op vrijdag 12 januari 2018 om 10.00 uur door Merijn Oudenampsen geboren op 1 december 1979 te Amsterdam Promotor: Prof. -

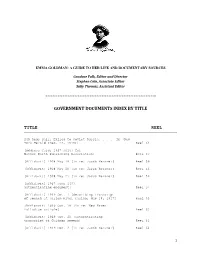

Government Documents Index by Title

EMMA GOLDMAN: A GUIDE TO HER LIFE AND DOCUMENTARY SOURCES Candace Falk, Editor and Director Stephen Cole, Associate Editor Sally Thomas, Assistant Editor GOVERNMENT DOCUMENTS INDEX BY TITLE TITLE REEL 249 Reds Sail, Exiled to Soviet Russia. In [New York Herald (Dec. 22, 1919)] Reel 64 [Address Card, 1917 July? for Mother Earth Publishing Association] Reel 57 [Affidavit] 1908 May 18 [in re: Jacob Kersner] Reel 56 [Affidavit] 1908 May 20 [in re: Jacob Kersner] Reel 56 [Affidavit] 1908 May 21 [in re: Jacob Kersner] Reel 56 [Affidavit] 1917 June 1[0? authenticating document] Reel 57 [Affidavit] 1919 Oct. 1 [describing transcript of speech at Harlem River Casino, May 18, 1917] Reel 63 [Affidavit] 1919 Oct. 18 [in re: New Haven Palladium article] Reel 63 [Affidavit] 1919 Oct. 20 [authenticating transcript of Goldman speech] Reel 63 [Affidavit] 1919 Dec. 2 [in re: Jacob Kersner] Reel 64 1 [Affidavit] 1920 Feb. 5 [in re: Abraham Schneider] Reel 65 [Affidavit] 1923 March 23 [giving Emma Goldman's birth date] Reel 65 [Affidavit] 1933 Dec. 26 [in support of motion for readmission to United States] Reel 66 [Affidavit? 1917? July? regarding California indictment of Alexander Berkman (excerpt?)] Reel 57 Affirms Sentence on Emma Goldman. In [New York Times (Jan. 15, 1918)] Reel 60 Against Draft Obstructors. In [Baltimore Sun (Jan. 15, 1918)] Reel 60 [Agent Report] In re: A.P. Olson (or Olsson)-- Anarchist and Radical, New York, 1918 Aug. 30 Reel 61 [Agent Report] In re: Abraham Schneider--I.W.W., St. Louis, Mo. [19]19 Oct. 14 Reel 63 [Agent Report In re:] Abraham Schneider, St. -

Dutch Political Parties on the European Union

MARCH 2017 Dutch political parties on Analysis the European Union The results of the Dutch national elections – Scenario 4 ‘Doing less more efficiently’ on March 15 are looked upon in the EU – Scenario 5 ‘Doing much more together’. as a possible precursor of the upcoming elections in France and Germany later this The expressed views of 14 Dutch political Michiel Luining year. Although the EU has hardly played parties can to some extent be linked to a role in the debates during the Dutch Juncker’s scenarios. Specific policy area election campaign, much of the international choices within the scenarios could differ debate has focused on whether an ‘anti-EU’ with the positions of the Dutch parties government will be elected. however. The EU positions of the Dutch political parties are best reflected in four While there are at least two political parties (other) categories as demonstrated below. that desire to leave the EU, this time an A more detailed overview of the priorities extraordinary amount of political parties of the political parties can be viewed in compete in the Dutch elections (at least the Mattermap. 14 serious contenders out of 28). As a result, as far as the EU is concerned, a 1. Leaving the EU (2 parties: PVV, variety of opinions exists. The outgoing Forum voor Democratie) Dutch government consists of two parties The (extreme) right wing party of Geert (a coalition of the VVD, centre right liberals, Wilders, the Party for Freedom (PVV), calls and the Labour Party), but if current polls are for a ‘Nexit’ and is currently still leading anything to go by, four or maybe five parties in most polls. -

What Is Left of the Radical Right?

This article from Politics of the Low Countries is published by Eleven international publishing and made available to anonieme bezoeker ARTICLES What Is Left of the Radical Right? The Economic Agenda of the Dutch Freedom Party 2006-2017 Simon Otjes* Abstract This article examines the economic agenda of the Dutch Freedom Party. It finds that this party mixes left-wing and right-wing policy positions. This inconsistency can be understood through the group-based account of Ennser-Jedenastik (2016), which proposes that the welfare state agenda of radical right-wing populist parties can be understood in terms of populism, nativism and authoritarianism. Each of these elements is linked to a particular economic policy: economic nativism, which sees the economic interest of natives and foreigners as opposed; economic populism, which seeks to limit economic privileges for the elite; and economic authoritarian‐ ism, which sees the interests of deserving and undeserving poor as opposed. By using these different oppositions, radical right-wing populist parties can reconcile left-wing and right-wing positions. Keywords: radical right-wing populist parties, economic policies, welfare chauvin‐ ism, populism, deserving poor. 1 Introduction Political scientists find it difficult to pinpoint the economic policy position of rad‐ ical right-wing populist parties. For instance, in the 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Sur‐ vey (CHES), the uncertainty around the average economic left-right estimate of radical right-wing populist parties (expressed as the standard error) was 80% greater than the uncertainty for liberal or social-democratic parties (Bakker et al., 2014; author’s calculations). Voters also find it difficult to place these parties.