The Oxfordian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APPENDIX 1 April 2018 to March 2021 Recommendations for the Community and Voluntary Organisations Grants Commissioning Programme

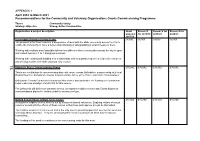

APPENDIX 1 April 2018 to March 2021 Recommendations for the Community and Voluntary Organisations Grants Commissioning Programme Theme Community Safety Strategic Objective Strong, Active Communities Organisation & project description Grant Recom’d Recom’d for Recom’d for awarded for 2018/19 2019/20 2020/21 2017/18 Donnington Doorstep Family Centre £8,000 £8,000 £8,000 £8,000 The proposal is for them to deliver a programme of work with the BME community across the City to enable the community to have a better understanding of safeguarding at what it means to them. Working with mothers and if possible fathers from different ethnic communities across the city in open and closed sessions, 1 to 1 and group sessions. Working with existing and building new relationships with local partner agencies to identify resources and develop toolkits on behalf of Oxford City Council. 75 Domestic Abuse Commissioning Group £35,082 £35,082 £35,082 £35,082 This is our contribution to commissioning domestic abuse across Oxfordshire in partnership with local District Councils, Oxfordshire County Council and the Office of the Police and Crime Commissioner. Oxfordshire County Council will commission this service and administer the funding our contribution helps makes up a budget of £600,000 for this service. For Oxford this will deliver an outreach service, a telephone helpline service and 5 local dispersed accommodation places for victims unable to access a refuge. Oxford Sexual Abuse & Rape Crisis Centre £15,000 £15,000 £15,000 £15,000 A telephone helpline service which is run by a team of trained volunteers. Enabling victims of sexual violence to deal with the effects of these crimes in their lives and improve access to information. -

Fall 2005 Shakespeare Matters Page 1

Fall 2005 Shakespeare Matters page 1 5:1 "Let me not to the marriage of true minds admit impediments..." Fall 2005 Falstaff in the Low Countries By Robert Detobel n his book Monstrous Adversary1 Prof. Alan Nelson has Oxford boast of his par ticipation in the battle of Bommel dur- Iing his visit to the Low Countries in the summer 1574. Nelson’s statement, my article shows, results from a double error. First he has failed to note the basic difference which existed between a battle and a siege in the Low Countries since 1573; second, and more James Newcomb, Fellowship member and Oregon Shakespeare Festival leading man, importantly, Nelson did not perceive (per- with Mark Anderson (right), winner of the 2005 Oxfordian of the Year Award. Newcomb haps because he did not want to) that Oxford’s stars this OSF season as a wickedly energetic Richard III. tale about his great feats was a Baron Münchhausen’s tall tale and was clearly so intended. More properly spoken it was a OSF, SF, and SOS Join Forces in “Falstaffiade, ” as will appear in the second part in which we observe the similarities between Oxford’s tale and Falstaff’s tales. Historic Conference (Continued on page 4) By Howard Schumann he first ever jointly sponsored conference of The Shakespeare Fellowship and The Shakespeare Oxford Society was a “breakthrough” and an important step in piercing the “bastion of orthodoxy” regarding the Shakespeare Tauthorship issue, according to James Newcomb, the Oregon ShakespeareFestival (OSF) actor who portrayed the villainous King Richard in the OSF’s magnificent production of Richard III. -

The Tragedy of King Richard the Third. Edited by A. Hamilton Thompson

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/3edtragedyofking00shakuoft OFC 1 5 iqo? THE ARDEN SHAKESPEARE W. GENERAL EDITOR: J. CRAIG 1899-1906: R. H. CASE, 1909 THE TRAGEDY OF KING RICHARD THE THIRD *^ ^*^ THE WORKS OF SHAKESPEARE THE TRAGEDY OF KING RICHARD THE THIRD EDITED BY A. HAMILTON THOMPSON . ? ^^ METHUEN AND CO. LTD. 86 ESSEX STREET: STRAND LONDON Thircf Edition First Published . August 22nd igoy Second Edition . August ^9^7 Third Edition . igi8 CONTENTS PAGB Introduction vii The Tragedy of King Richard the Third ... 7 Appendix I. 211 Appendix II 213 Appendix III. ......... 215 Appendix IV 220 " INTRODUCTION Six quarto editions of The Life and Death of Richard III. were published before the appearance of the folio of 1623. The title of the first quarto is : TRAGEDY OF King Richard THE | the third. Containing, His treacherous Plots against his | | brother Clarence: the pittiefull murther of his innocent | nephewes : his tyrannicall vsurpation : with the whole course | | of his detested life, and most deserued death. As it hath beene | lately the Right honourable the Chamber- Acted by | Lord | laine his seruants. [Prijnted by Valentine Sims, | At LONDON | for Wise, dwelling in Paules Chuch-yard \sic\ at Andrew | Signe of the Angell. the | 1597. I In the title of the second quarto (i 598), printed for Wise by Thomas Creede, the words " By William Shake-speare " occupy a new line after " seruants." The fourth, fifth, and sixth quartos also spell the author's name with a hyphen. The third quarto (1602), also printed by Creede, gives it as "Shakespeare," and adds, in a line above, the words " Newly augmented followed by a comma, which appear in the titles of the re- maining quartos. -

Ricardian Bulletin

Ricardian Bulletin Contents Summer 2007 2 From the Chairman 3 Strategy Update 9 Society News and Notices 12 Media Retrospective 14 News and Reviews 17 The Man Himself: by Tony Goodman 20 Medieval Migration: by Peter W. Lee 22 A Proclamation Against Henry Tudor, 23 June 1485: by David Candlin 25 Hastings and the Meeting at St Paul’s: by Gordon Smith 27 Chedworth Parish Church: by Gwen & Brian Waters 29 A ‘Lost’ Medieval Document: by Lynda Pidgeon 30 Logge Notes and Queries: Helen Barker’s Miracles by Lesley Boatwright 33 Correspondence 36 Guidelines for Contributors to the Bulletin 37 The Barton Library 40 New Members 41 Australasian Convention 2007 44 Report on Society Events 52 Future Society Events 55 Branch and Group Contacts - Update 55 Branches and Groups 58 Obituaries and Recently Deceased Members 60 Calendar Contributions Contributions are welcomed from all members. All contributions should be sent to the Technical Editor, Lynda Pidgeon. Bulletin Press Dates 15 January for Spring issue; 15 April for Summer issue; 15 July for Autumn issue; 15 October for Winter issue. Articles should be sent well in advance. Bulletin & Ricardian Back Numbers Back issues of the The Ricardian and Bulletin are available from Judith Ridley. If you are interested in obtaining any back numbers, please contact Mrs Ridley to establish whether she holds the issue(s) in which you are interested. For contact details see back inside cover of the Bulletin The Ricardian Bulletin is produced by the Bulletin Editorial Committee Printed by St Edmundsbury Press. © Richard III Society, 2007 1 From the Chairman ime for another issue of the Bulletin, and, all being well, you should have the 2007 edition T of The Ricardian too. -

Rrhe Sha Speare 9\Fiws{Etter

rrheSha�speare 9\fiws{etter Vo I.38:No.3 "What llewsfi'olll Oxford? Do thesejllsts alld triUlllphs hold?" Richard II 5.2 Summer 2002 Stylometrics and the This Strange Eventful History Funeral ElegyAffair Oxford, Shakespeare, and The Seven Ages of Man By Robert Brazil and Wayne Shore By Christopher Paul tylometrics refers to a growing body of "All the world's a stage" begins one of miseries of human life in much the same S techniques for analyzing written the most famous of Shakespeare's manner as Jaques, in a book which names material assisted by numerical analysis. monologues, the "Seven Ages of Man" the Earl of Oxford on the title page. Stylometrics has been applied in making speech voiced by the acerbic courtier Let us first begin with a briefoverview and refuting attributions of authorship. Jaques in As YO liLike It, Act 2, scene 7. of the origins ofJaques' speech. [Printed Comparative study ofEliza bethan texts As Jaques continues, he dryly and in full on page 15.] The iconography of began after concordances of Shakespeare entertainingly catalogs the ages, the Ages of Man was quite diverse, and his contemporaries were widely beginning with the mew ling infant, often evidencing conflation with the published in the early 20th Century. But it fo llowed by the whining school-boy, Ages of the World, the planets, the wasnot until the advent ofhome computing the sighing lover, the quarreling Deadly Sins, the days of the week, the that these databases could be effectively soldier, the prosing justice, the seasons, Fortune's Wheel, the compared with each other. -

LGBTQ+ Campaign

LGBTQ+ Campaign LGBTQ+ Campaign 1 CONTENTS INTRO 4 What is this and who is it for? 4 ADMINISTRATIVE QUESTIONS 5 How do I change my gender marker on my student record? 5 How do I change my name on my student record? 6 How do I change my title? 8 How do I change my name on my University Card(BodCard)? 8 Can I change the photo on my BodCard? 9 How do I change my name on my email? 10 How do I get my name changed on my pigeon hole (‘pidge’)? 11 What name will appear on my Degree Certificate? 11 How do I change my pronouns? 12 What records do college/the University keep of my name and gender marker? 12 What do I need to do to (re-)register to vote once I’ve changed my name? 13 HEALTH CARE QUESTIONS 14 How/where can I access trans-friendly doctors and healthcare? 14 Am I allowed to take time of for transitional purposes? 15 2 TRANS STUDENT OXFORD SURVIVAL GUIDE WELFARE QUESTIONS 16 How should I inform my academic tutors about my change of gender and/or name? 16 Which members of staf are a good point of contact? 17 Who can I talk to for welfare? Is there any student support in college? 19 FINANCE QUESTIONS 20 Can I apply for a transition fund through college? 20 What should I do if I’m facing financial dificulties because of my gender identity? 21 What should I do if my course involves travel abroad? 22 How do I change my name and gender with Student Finance England? 22 Do I need to buy a new sub fusc? 23 SOCIAL / OTHER QUESTIONS 23 Which hairdressers in Oxford are trans-friendly? 23 Where can I find gender-neutral toilets in town? 24 Are there any trans-inclusive sports groups? 25 Where can I find more support? 26 MY RIGHTS 28 What are my rights? 28 How do I report harassment? 29 Where can I find more information? 30 LGBTQ+ Campaign 3 INTRO What is this and who is it for? This is a guide put together by the Oxford SU LGBTQ+ Campaign’s Trans Rep of 2017/18 to provide practical information for trans students that should help them with various aspects of their transition in college and university. -

Attachment Data/File/404748/Align Change of Name G Uidance - V1 0.Pdf

Application: University of Oxford 2020 Workplace Equality Index Summary ID: A-1607368893 Last submitted: 9 Sep 2019 10:44 AM (UTC) Section 1: Employee Policy Completed - 16 Mar 2020 Workplace Equality Index submission Policies and Benefits: Part 1 Section 1: Policies and Benefits This section comprises of 7 questions and examines the policies and benefits the organisation has in place to support LGBT staff. The questions scrutinise policy audit process, policy content and communication. This section is worth 7.5% of your total score. Below each question you can see guidance on content and evidence. At any point, you may save and exit the form using the buttons at the bottom of the page. 1 / 135 1.1 Does the organisation have an audit process to ensure relevant policies (for example, HR policies) are explicitly inclusive of same-sex couples and use gender neutral language? GUIDANCE: The audit process should be systematic in its implementation across all relevant policies. Relevant policies include HR policies, for example leave policies. Yes Please describe the audit process: State when the process last happened: A proportionate review date is agreed for policies when they are created e.g. the Harassment Policy and Procedure has a three year review date (revised in 2014 and 2017). Describe the audit process: Governance at Oxford is democratic and its 70+ policies have been through a rigorous and widespread consultation and audit process in their creation and subsequent reviews. The process can take anything from six months to three years. With this in mind audits are not run concurrently. -

Summer 2006 Shakespeare Matters Page 1

Summer 2006 Shakespeare Matters page 1 5:4 "Let me not to the marriage of true minds admit impediments..." Summer 2006 “Stars or Suns:” The Portrayal of the Earls of Oxford in Elizabethan Drama By Richard Desper, PhD n Act III Scene vii of King Henry V, the proud nobles of France, gathered in camp on the eve of the battle of Agincourt, I speculate in anticipation of victory, letting their thoughts and their words take flight in fancy. While viewing the bedraggled English army as doomed, they savor their expected victory on the morrow and vie with each other in proclaiming their own glory. The dauphin1 boasts of his horse as another Pegasus, leading to a few allusions of a bawdy nature, and then a curious exchange takes place between Lord Rambures and the Constable of France, Professor William Leahy explains plans for a Shakespeare Charles Delabreth: Authorship Studies Master’s Program at Brunel University. Photo by William Boyle. Ram. My Lord Constable, the armor that I saw in your tent to-night, are those stars or suns upon it? Con. Stars, my lord. Brunel University to Offer 2 (Henry V, III.vii.63-5) Masters in Authorship Studies Shakespeare scholars have remarked little on these particular speeches, by default implying that they are words spoken in hile Concordia University has encouraged study of the passing, having no particular meaning other than idle chatter. Shakespeare authorship issue for years, Brunel One can count at least a dozen treatises on the text of Henry V that W University in England now plans to offer a graduate have nothing at all to say about these two lines.3 Yet numerous program leading to an M.A. -

The Single Equality Scheme Report of Public Engagement May 2009

APPENDIX 2 The Single Equality Scheme Report of Public Engagement May 2009 Author(s) Sara Price, Communications & Engagement Project Coordinator Status Final version Date 31st May 2009 Contents 1. ABOUT OXFORDSHIRE PCT............................................................................................- 3 - 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...................................................................................................- 4 - 2.1 BACKGROUND..................................................................................................................- 4 - 2.2 PURPOSE OF THE PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT REPORT.......................................................................- 4 - 2.3 PURPOSE OF ENGAGEMENT.................................................................................................- 4 - 2.4 PROCESS & METHODOLOGY................................................................................................- 5 - 2.5 KEY FINDINGS .................................................................................................................- 5 - 2.6 CONCLUSION...................................................................................................................- 6 - 3. BACKGROUND.................................................................................................................- 7 - 3.1 THE WIDER CONTEXT.........................................................................................................- 7 - Defining equality and diversity ...........................................................................................- -

Final Version

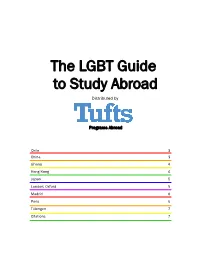

The LGBT Guide to Study Abroad Distributed by Programs Abroad Chile 3 China 3 Ghana 4 Hong Kong 4 Japan 5 London; Oxford 5 Madrid 6 Paris 6 Tübingen 7 Citations 7 Dear Student, The Pew Research Center conducted a world-wide survey between March and May of 2013 on the subject of homo- sexuality. They asked 37,653 participants in 39 countries, “Should society accept homosexuality?” The results, summariZed in this graphic, are revealing. There is a huge variance by region; some countries are extremely divided on the issue. Others have been, and continue to be, widely accepting of homosexuality. This information is relevant not only to residents of these countries, but to travelers and students who will be studying abroad. Students going abroad should be prepared for noted differences in attitudes toward individuals. Before depar- ture, it can be helpful for LGBT students to research cur- rent events pertaining to LGBT rights, general tolerance of LGBT persons, legal protection of LGBT individuals, LGBT organizations and support systems, and norms in the host culture’s dating scene. We hope that the following summaries will provide a starting point for the LGBT student’s exploration of their destination’s culture. If students are in homestay situations, they should consider the implications of coming out to their host family. Students may choose to conceal their sexual orientation to avoid tension in the student-host family relationship. Other times, students have used their time away from their home culture as an opportunity to come out. Some students have even described coming out overseas as a liberating experience, akin to a “second” coming out. -

A Royal Tragedy

William Shakespeare's Richard III A Royal Tragedy Acts Three, Four, and Five Notes Provided by WISDOM Home Schooling's Online Socratic Dialogue Progra Dramatis Personae KING EDWARD IV – The leader of the Yorkists, who beat the Lancastrian king, Henry VI, and took his throne. During the final battle that beat the Lancastrians, King Edward was one of the three men who dishonourably stabbed Lady Anne’s husband when he was already down. Edward used to be a great warrior, but has now become sickly, and is more interested in entertainment and women than in feats of courage. Sons to the King: EDWARD, PRINCE OF WALES – About thirteen years old. King Edward IV and Queen Elizabeth’s older son, and heir to the throne of England. Wise beyond his years, and protective of his brother. RICHARD, DUKE OF YORK – About ten years old. Prince Edward’s younger brother, he is second in line to inherit the throne. Less serious than his brother, he is given to joking around and making fun of adults. Brothers to the King: GEORGE, DUKE OF CLARENCE – Clarence is a conflicted man. During the war between the Yorkists and the Lancastrians, he fought on whichever side seemed to be winning at the time. He was one of the three who stabbed Lady Anne’s husband. Despite his shifting alliances, Clarence nonetheless has a deep love for his wife and children. RICHARD, DUKE OF GLOUCESTER (pronounced “Gloss-ter”), who will one day become KING RICHARD III – Gloucester is a hunchback with a withered arm and a limp. -

2019 Norton Elizabeth 121093

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The Blount Family in the long Sixteenth century Norton, Elizabeth Anna Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 The Blount Family in the Long Sixteenth Century Elizabeth Norton Doctor of Philosophy 2019 King’s College London 1 Abstract This thesis is an extended case study of the lives, attitudes, actions and concerns of one gentry family – the Blounts of the West Midlands –from the second half of the fifteenth century to the early years of the seventeenth, described as the long sixteenth century.