Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gandhi Warrior of Non-Violence P

SATYAGRAHA IN ACTION Indians who had spent nearly all their lives in South Africi Gandhi was able to get assistance for them from South India an appeal was made to the Supreme Court and the deportation system was ruled illegal. Meantime, the satyagraha movement continued, although more slowly as a result of government prosecution of the Indians and the animosity of white people to whom Indian merchants owed money. They demanded immediate payment of the entire sum due. The Indians could not, of course, meet their demands. Freed from jail once again in 1909, Gandhi decided that he must go to England to get more help for the Indians in Africa. He hoped to see English leaders and to place the problems before them, but the visit did little beyond acquainting those leaders with the difficulties Indians faced in Africa. In his nearly half year in Britain Gandhi himself, however, became a little more aware of India’s own position. On his way back to South Africa he wrote his first book. Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule. Written in Gujarati and later translated by himself into English, he wrote it on board the steamer Kildonan Castle. Instead of taking part in the usual shipboard life he used a packet of ship’s stationery and wrote the manuscript in less than ten days, writing with his left hand when his right tired. Hind Swaraj appeared in Indian Opinion in instalments first; the manuscript then was kept by a member of the family. Later, when its value was realized more clearly, it was reproduced in facsimile form. -

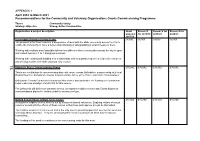

APPENDIX 1 April 2018 to March 2021 Recommendations for the Community and Voluntary Organisations Grants Commissioning Programme

APPENDIX 1 April 2018 to March 2021 Recommendations for the Community and Voluntary Organisations Grants Commissioning Programme Theme Community Safety Strategic Objective Strong, Active Communities Organisation & project description Grant Recom’d Recom’d for Recom’d for awarded for 2018/19 2019/20 2020/21 2017/18 Donnington Doorstep Family Centre £8,000 £8,000 £8,000 £8,000 The proposal is for them to deliver a programme of work with the BME community across the City to enable the community to have a better understanding of safeguarding at what it means to them. Working with mothers and if possible fathers from different ethnic communities across the city in open and closed sessions, 1 to 1 and group sessions. Working with existing and building new relationships with local partner agencies to identify resources and develop toolkits on behalf of Oxford City Council. 75 Domestic Abuse Commissioning Group £35,082 £35,082 £35,082 £35,082 This is our contribution to commissioning domestic abuse across Oxfordshire in partnership with local District Councils, Oxfordshire County Council and the Office of the Police and Crime Commissioner. Oxfordshire County Council will commission this service and administer the funding our contribution helps makes up a budget of £600,000 for this service. For Oxford this will deliver an outreach service, a telephone helpline service and 5 local dispersed accommodation places for victims unable to access a refuge. Oxford Sexual Abuse & Rape Crisis Centre £15,000 £15,000 £15,000 £15,000 A telephone helpline service which is run by a team of trained volunteers. Enabling victims of sexual violence to deal with the effects of these crimes in their lives and improve access to information. -

Working Group on Human Sexuality

IssuesTEXTwithoutPreface.qxp:Resourcbishops.qxp 20/11/2013 11:35 Page i The House of Bishops Working Group on human sexuality Published in book & ebook formats by Church House Publishing Available now from www.chpublishing.co.uk IssuesTEXTwithoutPreface.qxp:Resourcbishops.qxp 20/11/2013 11:35 Page ii Published in book & ebook formats by Church House Publishing Available now from www.chpublishing.co.uk IssuesTEXTwithoutPreface.qxp:Resourcbishops.qxp 20/11/2013 11:35 Page iii Report of the House of Bishops Working Group on human sexuality November 2013 Published in book & ebook formats by Church House Publishing Available now from www.chpublishing.co.uk IssuesTEXTwithoutPreface.qxp:Resourcbishops.qxp 20/11/2013 11:35 Page iv Church House Publishing All rights reserved. No part of this Church House publication may be reproduced or Great Smith Street stored or transmitted by any means London or in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, SW1P 3AZ recording, or any information storage and retrieval system without written permission, which should be sought ISBN 978 0 7151 4437 4 (Paperback) from [email protected] 978 0 7151 4438 1 (CoreSource EBook) 978 0 7151 4439 8 (Kindle EBook) Unless otherwise indicated, the Scripture quotations contained GS 1929 herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright Published 2013 for the House © 1989, by the Division of Christian of Bishops of the General Synod Education of the National Council of the Church of England by Church of the Churches of Christ in the -

1 Preliminary Proceedings

Notes 1 Preliminary proceedings 1. Jane McDermid, ‘Women and Education’, Women’s History: Britain, 1850–1945, ed. June Purvis (London: UCL, 1995), pp. 107–30 (p. 107). 2. Arthur Marwick, The Deluge: British Society and the First World War, 2nd edn (London: Macmillan, 1991), p. 134. 3. Ibid. 4. Jane Humphries, ‘Women and Paid Work’, Women’s History, ed. Purvis, pp. 15–105 (p. 89). 5. Penny Tinkler, ‘Women and Popular Literature’, Women’s History, ed. Purvis, pp. 131–56. 6. Ibid., p. 145. 7. Ibid., p. 146. 8. Alison Light, Forever England: Femininity, Literature and Conservatism Between the Wars (London: Routledge, 1991), pp. 9–10. 9. Ibid. 10. Earl F. Bargainnier, The Gentle Art of Murder: The Detective Fiction of Agatha Christie (Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green Press, 1980), p. 37. 11. Ann Heilmann, New Woman Fiction (London: Macmillan, 2000), p. 34. 12. Ibid., p. 35. 13. Patricia Marks, Bicycles, Bangs and Bloomers: The New Woman and the Popular Press (Lexington: University of Kentucky, 1990), p. 184. 14. Agatha Christie: An Autobiography (London: Fontana, 1977), p. 335. 15. Jared Cade, Agatha Christie and the Eleven Missing Days (London: Peter Own, 1998). 16. Lyn Pyket, Engendering Fictions (London: Arnold, 1995), p. 15. 17. Jane Elderidge Miller, Rebel Women: Feminism, Modernism and the Edwardian Novel (London: Virago, 1994), p. 4. 18. Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple: The Life and Times of Miss Jane Marple, first published in the US by Dodd Mead, 1985 (London: HarperCollins, 1997). 19. Ibid., p. 71. 20. Ibid., p. 45. 21. Anne Hart, Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The Life and Times of Hercule Poirot (London: Pavilion Books, 1990). -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

LGBTQ+ Campaign

LGBTQ+ Campaign LGBTQ+ Campaign 1 CONTENTS INTRO 4 What is this and who is it for? 4 ADMINISTRATIVE QUESTIONS 5 How do I change my gender marker on my student record? 5 How do I change my name on my student record? 6 How do I change my title? 8 How do I change my name on my University Card(BodCard)? 8 Can I change the photo on my BodCard? 9 How do I change my name on my email? 10 How do I get my name changed on my pigeon hole (‘pidge’)? 11 What name will appear on my Degree Certificate? 11 How do I change my pronouns? 12 What records do college/the University keep of my name and gender marker? 12 What do I need to do to (re-)register to vote once I’ve changed my name? 13 HEALTH CARE QUESTIONS 14 How/where can I access trans-friendly doctors and healthcare? 14 Am I allowed to take time of for transitional purposes? 15 2 TRANS STUDENT OXFORD SURVIVAL GUIDE WELFARE QUESTIONS 16 How should I inform my academic tutors about my change of gender and/or name? 16 Which members of staf are a good point of contact? 17 Who can I talk to for welfare? Is there any student support in college? 19 FINANCE QUESTIONS 20 Can I apply for a transition fund through college? 20 What should I do if I’m facing financial dificulties because of my gender identity? 21 What should I do if my course involves travel abroad? 22 How do I change my name and gender with Student Finance England? 22 Do I need to buy a new sub fusc? 23 SOCIAL / OTHER QUESTIONS 23 Which hairdressers in Oxford are trans-friendly? 23 Where can I find gender-neutral toilets in town? 24 Are there any trans-inclusive sports groups? 25 Where can I find more support? 26 MY RIGHTS 28 What are my rights? 28 How do I report harassment? 29 Where can I find more information? 30 LGBTQ+ Campaign 3 INTRO What is this and who is it for? This is a guide put together by the Oxford SU LGBTQ+ Campaign’s Trans Rep of 2017/18 to provide practical information for trans students that should help them with various aspects of their transition in college and university. -

The President of India, Rajendra Prasad, Bade Horace Alexander Farewell at A

FEBRUARY-MARCH 1952 The annual regional meeting for the AFSC will be held in three cities to allow maximum participation by members of the widespread Regional Committee and all other interested persons. Sessions in Dallas, Houston, and Austin will follow the same general program. Attenders ,./! are invited not only from these cities but from the vicinity. Of widest appeal will probably be the 8 p.m. meeting, offering "A Look at Europe and a Look at Asia." Olcutt The President of India, RaJendra Prasad, Sanders will report on his recent six bade Horace Alexander farewell at a spe months of visiting Quaker centers in cial reception in :ryew Delhi a few months Europe. Horace Alexander, for many ago. years director of the Quaker center in Delhi, India, will analyze the situation in Asia. A 6 p.m. supper meeting invites dis Horace Alexander, an English Friend cussion of developments in youth proj with long experience in India, will speak ects, employment on merit, and :peace at the annual regional AFSC meetings in education. More formal reports of nomi Dallas, Houston, and Austin. He will also nating, personnel, and finance committees speak at Corpus Christi at the Oak Park will come at 5 p.m. Methodist Church Sunday morning~ Feb ruary 24~ His address will be broadcasto DALLAS: WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 20 5 p.m. report meeting and 6 p.m. pot · He lectured in international relations luck supper at the new AFSC office, 2515 at Woodbrook College from 1919 to 1944. McKinney; phone Sterling 4691 for sug During visits to India in 1927 and 1930 he gestions of what you might bring. -

Crucibles of Virtue and Vice: the Acculturation of Transatlantic Army Officers, 1815-1945

CRUCIBLES OF VIRTUE AND VICE: THE ACCULTURATION OF TRANSATLANTIC ARMY OFFICERS, 1815-1945 John F. Morris Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2020 © 2020 John F. Morris All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Crucibles of Virtue and Vice: The Acculturation of Transatlantic Army Officers, 1815-1945 John F. Morris Throughout the long nineteenth century, the European Great Powers and, after 1865, the United States competed for global dominance, and they regularly used their armies to do so. While many historians have commented on the culture of these armies’ officer corps, few have looked to the acculturation process itself that occurred at secondary schools and academies for future officers, and even fewer have compared different formative systems. In this study, I home in on three distinct models of officer acculturation—the British public schools, the monarchical cadet schools in Imperial Germany, Austria, and Russia, and the US Military Academy—which instilled the shared and recursive sets of values and behaviors that constituted European and American officer cultures. Specifically, I examine not the curricula, policies, and structures of the schools but the subterranean practices, rituals, and codes therein. What were they, how and why did they develop and change over time, which values did they transmit and which behaviors did they perpetuate, how do these relate to nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century social and cultural phenomena, and what sort of ethos did they produce among transatlantic army officers? Drawing on a wide array of sources in three languages, including archival material, official publications, letters and memoirs, and contemporary nonfiction and fiction, I have painted a highly detailed picture of subterranean life at the institutions in this study. -

ND March 2020.Pdf

ELLAND All Saints , Charles Street, HX5 0LA A Parish of the Soci - ety under the care of the Bishop of Wakefield . Serving Tradition - alists in Calderdale. Sunday Mass 9.30am, Rosary/Benediction usually last Sunday, 5pm. Mass Tuesday, Friday & Saturday, parish directory 9.30am. Canon David Burrows SSC , 01422 373184, rectorofel - [email protected] BATH Bathwick Parishes , St.Mary’s (bottom of Bathwick Hill), BROMLEY St George's Church , Bickley Sunday - 8.00am www.ellandoccasionals.blogspot.co.uk St.John's (opposite the fire station) Sunday - 9.00am Sung Mass at Low Mass, 10.30am Sung Mass. Daily Mass - Tuesday 9.30am, St.John's, 10.30am at St.Mary's 6.00pm Evening Service - 1st, Wednesday 9.30am, Holy Hour, 10am Mass Friday 9.30am, Sat - FOLKESTONE Kent , St Peter on the East Cliff A Society 3rd &5th Sunday at St.Mary's and 2nd & 4th at St.John's. Con - urday 9.30am Mass & Rosary. Fr.Richard Norman 0208 295 6411. Parish under the episcopal care of the Bishop of Richborough . tact Fr.Peter Edwards 01225 460052 or www.bathwick - Parish website: www.stgeorgebickley.co.uk Sunday: 8am Low Mass, 10.30am Solemn Mass. Evensong 6pm parishes.org.uk (followed by Benediction 1st Sunday of month). Weekday Mass: BURGH-LE-MARSH Ss Peter & Paul , (near Skegness) PE24 daily 9am, Tues 7pm, Thur 12 noon. Contact Father Mark Haldon- BEXHILL on SEA St Augustine’s , Cooden Drive, TN39 3AZ 5DY A resolution parish in the care of the Bishop of Richborough . Jones 01303 680 441 http://stpetersfolk.church Saturday: Mass at 6pm (first Mass of Sunday)Sunday: Mass at Sunday Services: 9.30am Sung Mass (& Junior Church in term e-mail :[email protected] 8am, Parish Mass with Junior Church at1 0am. -

Jessica Mitford

Jessica Mitford: An Inventory of Her Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator Mitford, Jessica, 1917-1996 Title Jessica Mitford Papers Dates: 1949-1973 Extent 67 document boxes, 3 note card boxes, 7 galley files, 1 oversize folder (27 linear feet) Abstract: Correspondence, printed material, reports, notes, interviews, manuscripts, legal documents, and other materials represent Jessica Mitford's work on her three investigatory books and comprise the bulk of these papers. Language English. Access Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition Purchase, 1973 Processed by Donald Firsching, Amanda McCallum, Jana Pellusch, 1990 Repository: Harry Ransom Center University of Texas at Austin Mitford, Jessica, 1917-1996 Biographical Sketch Born September 11, 1917, in Batsford, Gloucestershire, England, Jessica Mitford is one of the six daughters of the Baron of Redesdale. The Mitfords are a well-known English family with a reputation for eccentricity. Of the Mitford sisters, Nancy achieved notoriety as a novelist and biographer. Diana married Sir Oswald Mosley, leader of the British fascists before World War II. Unity, also a fascist sympathizer, attempted suicide when Britain and Germany went to war. Deborah became the Duchess of Devonshire. Jessica, whose political bent ran opposite to that of her sisters, ran away to Loyalist Spain with her cousin, Esmond Romilly, during the Spanish Civil War. Jessica eventually married Romilly, who was killed during World War II. In 1943, Mitford married a labor lawyer, Robert Treuhaft, while working for the Office of Price Administration in Washington, D.C. The couple soon moved to Oakland, California, where they joined the Communist Party. In California, Mitford worked as executive secretary for the Civil Rights Congress and taught sociology at San Jose State University. -

Detention Without Trial in the Second World War: Comparing the British and American Experiences A.W

Florida State University Law Review Volume 16 | Issue 2 Article 1 Summer 1988 Detention without Trial in the Second World War: Comparing the British and American Experiences A.W. Brian Simpson University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation A.W. B. Simpson, Detention without Trial in the Second World War: Comparing the British and American Experiences, 16 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 225 (2017) . http://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol16/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 16 SUMMER 1988 NUMBER 2 DETENTION WITHOUT TRIAL IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR: COMPARING THE BRITISH AND AMERICAN EXPERIENCES A.W. BRIAN SIMPSON* National security has long been advanced as a justification for the abrogation of civil liberties. In this lecture, Professor Simpson examines through the analysis of particular cases how two nations dealt with these competing values in the internment without trial of their respective citizens during World War I. Condemning the secrecy and lack of accountability of the authorities responsible for protecting the nation, Simpson issues a call for vigilance and a warning that patterns and habits of respect for liberty will serve better than mere forms of procedure to effectively insure that liberties are not again abandoned to ill-founded claims of defense necessity. -

School of Oriental and African Studies)

BRITISH ATTITUDES T 0 INDIAN NATIONALISM 1922-1935 by Pillarisetti Sudhir (School of Oriental and African Studies) A thesis submitted to the University of London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1984 ProQuest Number: 11010472 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010472 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT This thesis is essentially an analysis of British attitudes towards Indian nationalism between 1922 and 1935. It rests upon the argument that attitudes created paradigms of perception which condi tioned responses to events and situations and thus helped to shape the contours of British policy in India. Although resistant to change, attitudes could be and were altered and the consequent para digm shift facilitated political change. Books, pamphlets, periodicals, newspapers, private papers of individuals, official records, and the records of some interest groups have been examined to re-create, as far as possible, the structure of beliefs and opinions that existed in Britain with re gard to Indian nationalism and its more concrete manifestations, and to discover the social, political, economic and intellectual roots of the beliefs and opinions.