REFLECTIONS by CARD. WALTER KASPER Current Problems In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baptists, Bishops and the Sacerdotal Ministry

374 BAPTISTS, BISHOPS AND THE SACERDOTAL MINISTRY As a Baptist who before my ordination frequently presided at the Lord's Table - and on one occasion in the presence of no less than four Anglican priests (one of whom is now secretary to the Board of Mission and Unity) - I am by no means a l,ikely advocate of a fully sacerdotal ministry. Nevertheless, my view of ministry is what I would call a "high" view, which, combined with my in terest in symbol, ritual and liturgy has led some to label me a "Bapto-Catholic". I pray, however, that my view of ministry is not "high" because of personal pride in my own office, but out of humble recognition that despite my unworthiness, Christ has seen fit to call me and equip me as a Minister of Word and Sacra ment. I believe, moreover, that my "high" view of the ministry is consistent with,much of Baptist history. Indeed, the Baptist Statement of 1948 declared that "Baptists have had from the be ginning an exalted concept of the office of the christian minis- :' ter".l I will even go so far as to say (being in a provocative mood) that episcopacy - that highest of all concepts of ministry - also has a place in Baptist tradition. I will begin my defence where all good Baptists begin, with the Bible, by examining briefly the Biblical basis of episcope. In I Peter 2.25, Christ himself is described as the episcopos of our souis (translated as "guardian" in the R.S.V.). He is the Over-seer of the Church, His Body, of which He is the Head. -

40"" Anniversary of Del Verbum International Congress "Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church" CATHOLIC BIBLICAL FEDERATION 4T

VERBUM ic Biblical Federation I I I I I } i V \ 40"" Anniversary of Del Verbum International Congress "Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church" CATHOLIC BIBLICAL FEDERATION 4t BULLETIN DEI VERBUM is a quarterly publica tion in English, French, German and Spanish. Editors Alexander M. Schweitzer Glaudio EttI Assistant to the editors Dorothea Knabe Production and layout bm-projekte, 70771 Leinf.-Echterdingen A subscription for one year consists of four issues beginning the quarter payment is Dei Verbum Congress 2005 received. Please indicate in which language you wish to receive the BULLETIN DEI VERBUM. Summary Subscription rates ■ Ordinary subscription: US$ 201 €20 ■ Supporting subscription: US$ 34 / € 34 Audience Granted by Pope Benedict XVI « Third World countries: US$ 14 / € 14 ■ Students: US$ 14/€ 14 Message of the Holy Father Air mail delivery: US$ 7 / € 7 extra In order to cover production costs we recom mend a supporting subscription. For mem Solemn Opening bers of the Catholic Biblical Federation the The Word of God In the Life of the Church subscription fee is included in the annual membership fee. Greeting Address by the CBF President Msgr. Vincenzo Paglia 6 Banking details General Secretariat "Ut Dei Verbum currat" (Address as indicated below) LIGA Bank, Stuttgart Opening Address of the Exhibition by the CBF General Secretary A l e x a n d e r M . S c h w e i t z e r 1 1 Account No. 64 59 820 IBAN-No. DE 28 7509 0300 0006 4598 20 BIO Code GENODEF1M05 Or per check to the General Secretariat. -

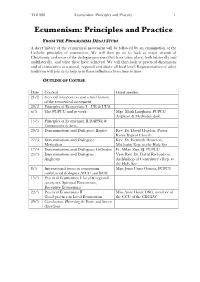

Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 1 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice FROM THE PROGRAMMA DEGLI STUDI A short history of the ecumenical movement will be followed by an examination of the Catholic principles of ecumenism. We will then go on to look at major strands of Christianity and some of the dialogue processes that have taken place, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and what these have achieved. We will then look at practical dimensions and of ecumenism at national, regional and above all local level. Representatives of other traditions will join us to help us in these reflections from time to time. OUTLINE OF COURSE Date Content Guest speaker 21/2 General introduction and a brief history of the ecumenical movement 28/2 Principles of Ecumenism I – UR & UUS 6/3 The PCPCU and its work Mgr. Mark Langham, PCPCU Anglican & Methodist desk. 13/3 Principles of Ecumenism II DAPNE & Communicatio in Sacris 20/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Baptist Rev. Dr. David Hogdon, Pastor, Rome Baptist Church. 27/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Rev. Dr. Kenneth Howcroft, Methodists Methodist Rep. to the Holy See 17/4 Denominations and Dialogues: Orthodox Fr. Milan Zust SJ, PCPCU 24/4 Denominations and Dialogues : Very Rev. Dr. David Richardson, Anglicans Archbishop of Canterbury‘s Rep. to the Holy See 8/5 International issues in ecumenism, Mgr. Juan Usma Gomez, PCPCU multilateral dialogues ,WCC and BEM 15/5 Practical Ecumenism I: local & regional structures, Spiritual Ecumenism, Receptive Ecumenism 22/5 Practical Ecumenism II Miss Anne Doyle DSG, member of Good practice in Local Ecumenism the CCU of the CBCEW 29/5 Conclusion: Harvesting the Fruits and future directions TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 2 Ecumenical Resources CHURCH DOCUMENTS Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redentigratio (1964) PCPCU Directory for the Application of the Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (1993) Pope John Paul II Ut Unum Sint. -

The Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral: Development in an Anglican Approach to Christian Unity

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Electrical and Computer Engineering Faculty Research and Publications/College of Engineering This paper is NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; but the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be accessed by following the link in the citation below. Journal of Ecumenical Studies, Vol. 33, No. 4 (Fall 1996): 471-486. Publisher link. This article is © University of Pennsylvania Press and permission has been granted for this version to appear in e- Publications@Marquette. University of Pennsylvania Press does not grant permission for this article to be further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from University of Pennsylvania Press. THE CHICAGO-LAMBETH QUADRILATERAL: DEVELOPMENT IN AN ANGLICAN APPROACH TO CHRISTIAN UNITY Robert B. Slocum Theology, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI PRECIS The Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral has served as the primary reference point and working document of the Anglican Communion for ecumenical Christian reunion. It identifies four essential elements for Christian unity in terms of scriptures, creeds, sacraments, and the Historic Episcopate. The Quadrilateral is based on the ecumenical thought and leadership of William Reed Huntington, an Episcopal priest who proposed the Quadrilateral in his book The Church.Idea:/In Essay toward Unity (1870) and who was the moving force behind approval of the Quadrilateral by the House of Bishops of the 1886 General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church. It was subsequently approved with modifications by the Lambeth Conference of 1888 and finally reaffirmed in its Lambeth form by the General Convention of the Episcopal Church in 1895. The Quadrilateral has been at the heart of Anglican ecumenical discussions and relationships since its approval Interpretation of the meaning of the Quadrilateral has undergone considerable development in its more than 100-year history. -

Article Reviews Walter Kasper on the Catholic Church

ecclesiology 14 (2018) 203-211 ECCLESIOLOGY brill.com/ecso Article Reviews ∵ Walter Kasper on the Catholic Church Susan K. Wood Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, usa [email protected] Walter Kasper The Catholic Church: Nature, Reality and Mission, trans. Thomas Hoebel (London and New York: Bloomsbury, T&T Clark, 2015), xviii + 463 pp. isbn 978-1-4411-8709-3 (pbk). $54.95. The Catholic Church: Nature – Reality – Mission, following more than twenty years after Jesus the Christ and The God of Jesus Christ, is the third volume of a trilogy, their Christological unity indicated by their German titles: Jesus Der Christus (1974), Der Gott Jesu Christi (1982) and Die Kirche Jesu Christi (2008). Life had intervened in the interim, first by Kasper’s service as bishop of Rottenburg- Stuttgart (1989–1999), followed by eleven years with the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity (1999–2010) where he was its cardinal prefect from 2001. This interim period also included his work as theological secretary of the Extraordinary Synod (1985) which had identified communio as a central theme and guiding principle of the Second Vatican Council. His life in and for the church had interrupted his theological work on a systematic treatise on the church, fortuitous for an ecclesiology that not only reflects develop- ment since the Second Vatican Council, but also aims to be an existential ec- clesiology relevant for both the individual and society. He comments that an ecclesiology for today must perceive the crisis of the Church manifested by decreasing church attendance, decline in participation in the sacraments, and priest shortages in connection with the crises of today’s world in a post- Constantinian time (p. -

This Article First Presents the Status Questionis of the Issue of Communion for the Remarried Divorcees

EUCHARISTIC COMMUNION FOR THE REMARRIED D IVORCEES: IS AMORIS LAETITIA THE FINAL ANSWER? RAMON D. ECHICA This article first presents the status questionis of the issue of communion for the remarried divorcees. There is an interlocution between the affirmative answer represented by Walter Kasper and the negative answer represented by Carlo Caffara and Gerhard Mueller. The article then offers two theological concepts not explicitly mentioned in Amoris Laetitia to buttress the affirmative answer. INTRODUCTION THE CONTEXT OF THE ISSUE rom the Synod of the Family of 2014, then followed by a bigger Fsynod on the same subject a year after, up to the issuance of the Apostolic Exhortation Amoris Laetitia (AL), what got the most media attention was the issue of the reception of Eucharistic communion by divorcees, whose marriages have never been declared null by the Church and who have entered a second (this time purely civil or state) marriage. The issue became the subject matter of some reasoned theological discourse but also of numerous acrimonious debates. Three German bishops, namely Walter Kasper, Karl Lehman and Oskar Saier were the first prominent hierarchical members who openly raised the issue through a pastoral letter in 1993.1Nothing much came out of it until Pope Francis signaled his 1 Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger thumbed down the proposal in 1994. For a brief history of the earlier attempts to allow divorcees to receive communion, see Lisa Duffy, “Pope Benedict Already Settled the Question of Communion for the Hapág 13, No. 1-2 (2016) 49-69 EUCHARISTIC COMMUNION FOR THE REMARRIED DIVORCESS openness to rethink the issue. -

Evangelicals and the Synoptic Problem

EVANGELICALS AND THE SYNOPTIC PROBLEM by Michael Strickland A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Theology and Religion School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion University of Birmingham January 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Dedication To Mary: Amor Fidelis. In Memoriam: Charles Irwin Strickland My father (1947-2006) Through many delays, occasioned by a variety of hindrances, the detail of which would be useless to the Reader, I have at length brought this part of my work to its conclusion; and now send it to the Public, not without a measure of anxiety; for though perfectly satisfied with the purity of my motives, and the simplicity of my intention, 1 am far from being pleased with the work itself. The wise and the learned will no doubt find many things defective, and perhaps some incorrect. Defects necessarily attach themselves to my plan: the perpetual endeavour to be as concise as possible, has, no doubt, in several cases produced obscurity. Whatever errors may be observed, must be attributed to my scantiness of knowledge, when compared with the learning and information necessary for the tolerable perfection of such a work. -

Oblates to Celebrate Life of Mother Mary Lange,Special Care Collection

Oblates to celebrate life of Mother Mary Lange More than 30 years before the Emancipation Proclamation, Mother Mary Lange fought to establish the first religious order for black women and the first black Catholic school in the United States. To honor the 126th anniversary of their founder’s death, the Oblate Sisters of Providence have planned a Feb. 3 Mass of Thanksgiving at 1 p.m., which will be celebrated by Cardinal William H. Keeler in the Our Lady of Mount Providence Convent Chapel in Catonsville. The Mass will be followed by a reception, offering guests the opportunity to view Mother Mary Lange memorabilia. A novena will also be held Jan. 25-Feb. 2 in the chapel. Sister M. Virginie Fish, O.S.P., and several of her colleagues in the Archdiocese of Baltimore have devoted nearly 20 years to working on the cause of canonization for Mother Mary Lange, who, along with Father James Hector Joubert, S.S., founded the Oblate Sisters in 1829. With the help of two other black women, Mother Mary Lange also founded St. Frances Academy, Baltimore, in 1828, which is the first black Catholic school in the country and still in existence. Sister Virginie said the sisters see honoring Mother Mary Lange as a fitting way to kick-start National Black History Month. Father John Bowen, S.S., postulator for Mother Mary Lange’s cause, completed the canonization application three years ago and sent it to Rome, where it is currently under review. There is no timetable for the Vatican to complete or reject sainthood for Mother Mary Lange, Father Bowen said. -

Bishop Celebrates 50Th Anniversary Mass at Marian High School

September 21, 2014 Think Green 50¢ Recycle Volume 88, No. 30 Go Green todayscatholicnews.org Serving the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend Go Digital ’’ RED MASS OPEN TO TTODAYODAYSS CCATHOLICATHOLIC ALL THE FAITHFUL A Red Mass will be held Wednesday, Sept. 24, at 5:30 p.m. Bishop celebrates 50th anniversary at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Fort Wayne. The South Bend area Mass at Marian High School Red Mass will be Monday, Oct. 6, at 5:15 p.m. at the BY CHRISTOPHER LUSHIS Basilica of the Sacred Heart MISHAWAKA — “Put out into the See pages 13-14 deep!” announced Bishop Kevin C. Rhoades to the Marian High School community during their golden anni- versary Mass on Sept. 4. This joyous occasion commemorated the com- Tribute pletion of the endeavor undertaken by the sixth bishop of the Diocese Father Chrobot dies of Fort Wayne-South Bend, Bishop Leo A. Pursley, to construct a sec- Page 3 ond Catholic high school to serve the needs of the South Bend and Mishawaka area in 1964. Present for this special Mass Congregation were Benedictine Father Jonathan Fassero, a member of the first gradu- of Holy Cross ating class of 1968 from Marian, and Msgr. Michael Heintz, rector of Six make final vows, St. Matthew Cathedral and a 1985 graduate. Also in attendance were ordained deacons priests from St. Jude, St. Anthony de KEVIN HAGGENJOS Page 5 Padua, St. Bavo, St. Matthew and St. th Thomas Parishes, as well as priests Bishop Kevin C. Rhoades celebrates Mass on Thursday, Sept. -

Philadelphia Meeting, Synods Will Be Part of Debate on Families

The CatholicWitness The Newspaper of the Diocese of Harrisburg September 26, 2014 Vol. 48 No. 18 CHRIS HEISEY, THE CATHOLIC WITNESS The colors of Hispanic heritage filled St. Patrick Cathedral and the steps of the state Capitol in Harrisburg Sept. 14 for the Diocesan Hispanic Heritage Mass. The celebration displayed the culture and gifts of Hispanic Catholics, and marked the 70th anniversary of ministry to Spanish-speaking Catholics in the diocese. See cover- age of the Mass and the Hispanic Apostolate on pages 8 and 9. Philadelphia Meeting, Synods Will be Part of Debate on Families By Francis X. Rocca Pope Francis has said both synods will con- Catholic News Service sider, among other topics, the eligibility of divorced and civilly remarried Catholics to The World Meeting of Families in Phila- receive Communion, whose predicament he delphia in September 2015 will serve as a has said exemplifies a general need for mercy forum for debating issues on the agenda for in the church today. the world Synod of Bishops at the Vatican the “We’re bringing up all the issues that would following month, said the two archbishops re- have appeared in the preparation documents sponsible for planning the Philadelphia event. for the synod as part of our reflection,” said At a Sept. 16 briefing, Archbishop Vincen- Archbishop Charles J. Chaput of Philadel- zo Paglia, president of the Pontifical Council phia, regarding plans for the world meeting. for the Family, described the world meeting “I can’t imagine that any of the presenters as one of several related events to follow the won’t pay close attention to what’s happen- October 2014 extraordinary Synod of Bishops ing” in Rome. -

Mercy Is a Person: Pope Francis and the Christological Turn in Moral Theology

Journal of Moral Theology, Vol. 6, No. 2 (2017): 48-69 Mercy Is a Person: Pope Francis and the Christological Turn in Moral Theology Alessandro Rovati Before all else, the Gospel invites us to respond to the God of love who saves us, to see God in others and to go forth from ourselves to seek the good of others. […] If this invitation does not radiate forcefully and attractively, the edifice of the Church’s moral teaching risks becoming a house of cards, and this is our greatest risk. It would mean that it is not the Gospel which is being preached, but certain doctrinal or moral points based on specific ideological options. The message will run the risk of losing its freshness and will cease to have ‘the fragrance of the Gospel’ (Evangelii Gaudium, no. 39). HESE WORDS FROM THE APOSTOLIC Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium represent one of the main concerns of Francis’s pontificate, namely, the desire to call the Church back to the heart of the Gospel message so that her preaching may not T 1 be distorted or reduced to some of its secondary aspects. Francis put it strongly in the famous interview he released to his Jesuit brother Antonio Spadaro, “The Church’s pastoral ministry cannot be obsessed with the transmission of a disjointed multitude of doctrines to be imposed insistently. Proclamation in a missionary style focuses on the essentials, on the necessary things: this is also what fascinates and attracts more, what makes the heart burn. … The proposal of the gospel must be more simple, profound, radiant. -

Association of Catholic Publishers • News Release

Association of Catholic Publishers • News Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Therese Brown, [email protected] May 18, 2016 Mercy Dominates as Theme of 2016 ACP Excellence in Publishing Awards Binz Wins Two Awards in Two Different Categories Liturgical Press Is Publisher of the 2016 “Book of the Year” BALTIMORE, MD — The Association of Catholic Publishers (ACP) is pleased to announce the winners of the new Excellence in Publishing Awards, which will be given out at the 20th Annual Catholic Marketing Network International Trade Show in Schaumburg, Illinois. The goal of these awards is to recognize the best in Catholic publishing. “In the midst of this Year of Mercy, it is not surprising to see winners that focus on mercy and kindness explicitly,” stated Therese Brown, executive director of the Association of Catholic Publishers. “What is truly interesting are the number of award-winning titles that illustrate those traits in the lives of “saints,” some canonized and others not.” The 2016 “Book of the Year” is To Be One in Christ by Edward P. Hahnenberg from Liturgical Press. “This book will be very helpful for a Church called to embrace multicultural, multiethnic and multilingual issues that face pastoral ministers,” commented one of the judges. “With an in-depth examination of theological, cultural, sociological, and ecumenical perspectives, this book will be a useful companion for pastors, parish life, and all in pastoral formation. This book should be required reading for all pastors and those in seminary formation.” The “Book of the Year” is selected from among the first-place finishers. Liturgical Press walks away with 6 awards including 3 first place finishers and the Book of the Year.