Dam Building by the Illiberal Modernisers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organized Crime and Instability in Central Africa

Organized Crime and Instability in Central Africa: A Threat Assessment Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: +(43) (1) 26060-0, Fax: +(43) (1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org OrgAnIzed CrIme And Instability In CenTrAl AFrica A Threat Assessment United Nations publication printed in Slovenia October 2011 – 750 October 2011 UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Organized Crime and Instability in Central Africa A Threat Assessment Copyright © 2011, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Acknowledgements This study was undertaken by the UNODC Studies and Threat Analysis Section (STAS), Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs (DPA). Researchers Ted Leggett (lead researcher, STAS) Jenna Dawson (STAS) Alexander Yearsley (consultant) Graphic design, mapping support and desktop publishing Suzanne Kunnen (STAS) Kristina Kuttnig (STAS) Supervision Sandeep Chawla (Director, DPA) Thibault le Pichon (Chief, STAS) The preparation of this report would not have been possible without the data and information reported by governments to UNODC and other international organizations. UNODC is particularly thankful to govern- ment and law enforcement officials met in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda and Uganda while undertaking research. Special thanks go to all the UNODC staff members - at headquarters and field offices - who reviewed various sections of this report. The research team also gratefully acknowledges the information, advice and comments provided by a range of officials and experts, including those from the United Nations Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, MONUSCO (including the UN Police and JMAC), IPIS, Small Arms Survey, Partnership Africa Canada, the Polé Institute, ITRI and many others. -

African Development Bank United Republic of Tanzania

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA DODOMA CITY OUTER RING ROAD (110.2 km) CONSTRUCTION PROJECT APPRAISAL REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure RDGE/PICU DEPARTMENTS April 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. STRATEGIC THRUST AND JUSTIFICATIONS ............................................................................... 1 1.1 PROJECT LINKAGES WITH NATIONAL AND REGIONAL STRATEGIES ........................................................ 1 1.2 RATIONALE FOR BANK INVOLVEMENT .................................................................................................. 1 1.3 AID COORDINATION ............................................................................................................................. 2 II. PROJECT DESCRIPTION ................................................................................................................... 2 2.1 PROJECT OBJECTIVES ........................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 PROJECT COMPONENTS ........................................................................................................................ 3 2.3 TECHNICAL SOLUTIONS ADOPTED AND ALTERNATIVES CONSIDERED .................................................... 3 2.4 PROJECT TYPE ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2.5 PROJECT COST AND FINANCING MECHANISMS ..................................................................................... -

Issued by the Britain-Tanzania Society No 124 Sept 2019

Tanzanian Affairs Issued by the Britain-Tanzania Society No 124 Sept 2019 Feathers Ruffled in CCM Plastic Bag Ban TSh 33 trillion annual budget Ben Taylor: FEATHERS RUFFLED IN CCM Two former Secretary Generals of the ruling party, CCM, Abdulrahman Kinana and Yusuf Makamba, stirred up a very public argument at the highest levels of the party in July. They wrote a letter to the Elders’ Council, an advisory body within the party, warning of the dangers that “unfounded allegations” in a tabloid newspaper pose to the party’s “unity, solidarity and tranquillity.” Selection of newspaper covers from July featuring the devloping story cover photo: President Magufuli visits the fish market in Dar-es-Salaam following the plastic bag ban (see page 5) - photo State House Politics 3 This refers to the frequent allegations by publisher, Mr Cyprian Musiba, in his newspapers and on social media, that several senior figures within the party were involved in a plot to undermine the leadership of President John Magufuli. The supposed plotters named by Mr Musiba include Kinana and Makamba, as well as former Foreign Affairs Minister, Bernard Membe, various opposition leaders, government officials and civil society activists. Mr Musiba has styled himself as a “media activist” seeking to “defend the President against a plot to sabotage him.” His publications have consistently backed President Magufuli and ferociously attacked many within the party and outside, on the basis of little or no evidence. Mr Makamba and Mr Kinana, who served as CCM’s secretary generals between 2009 to 2011 and 2012-2018 respectively, called on the party’s elders to intervene. -

India-Tanzania Bilateral Relations

INDIA-TANZANIA BILATERAL RELATIONS Tanzania and India have enjoyed traditionally close, friendly and co-operative relations. From the 1960s to the 1980s, the political relationship involved shared commitments to anti-colonialism, non-alignment as well as South-South Cooperation and close cooperation in international fora. The then President of Tanzania (Mwalimu) Dr. Julius Nyerere was held in high esteem in India; he was conferred the Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding for 1974, and the International Gandhi Peace Prize for 1995. In the post-Cold War period, India and Tanzania both initiated economic reform programmes around the same time alongside developing external relations aimed at broader international political and economic relations, developing international business linkages and inward foreign investment. In recent years, India-Tanzania ties have evolved into a modern and pragmatic relationship with sound political understanding, diversified economic engagement, people to people contacts in the field of education & healthcare, and development partnership in capacity building training, concessional credit lines and grant projects. The High Commission of India in Dar es Salaam has been operating since November 19, 1961 and the Consulate General of India in Zanzibar was set up on October 23, 1974. Recent high-level visits Prime Minister Mr. Narendra Modi paid a State Visit to Tanzania from 9-10 July 2016. He met the President of Tanzania, Dr. John Pombe Joseph Magufuli for bilateral talks after a ceremonial -

1. KONDOA DISTRICT COUNCIL No Name of the Project Opportunities

1. KONDOA DISTRICT COUNCIL No Name of Opportunities Geographic Location Land Ownership Ongoing activities Competitive advantage the Project for investors 1. BUKULU Establishment Bukulu Industrial Area is Bukulu Industrial plot There is currently no Bukulu Industrial Area will serve Industrial of Located at Soera ward in area is owned by Kondoa established structure the growing demand for areas Area Manufacturing Kondoa District, Dodoma District Council at Bukulu Industrial to invest in manufacturing Industries Region Future ownership of the Area plot (green The plot is designated for The size of Bukulu land will be discussed field). No demolition manufacturing and located Industrial Area is 400 between the Developer work is needed by about 220km from the Acres and the owner Investor proposed dry port of Ihumwa Bukulu Industrial Area is Investors will be Manufacturing is aligned with located 47km from required to remove Government Five Year Kondoa Town and 197km some shrubs and Development Plan – II (FYDP – from Dodoma Town. conduct other site II) which promotes The Plot is located just off clearance activities industrialisation the main highway from The prospective Industrial Area Dodoma to Arusha is set to enjoy all the necessary The Area is closer to all infrastructures since it is just the necessary 197km from Government infrastructures Capital – Dodoma (electricity, water and The plot is located along the communications) Dodoma – Arusha highway Bukulu area is designated which is the longest and busiest for manufacturing Trans – African transportation Industries corridor linking Cape Town (South Africa) and Cairo (Egypt) 2. PAHI Establishment Pahi Industrial Area is Pahi Industrial plot area There is currently no Pahi Industrial Area will serve Industrial of Located at Pahi ward in is owned by Kondoa established structure the growing demand for areas Area Manufacturing Kondoa District, Dodoma District Council at Pahi Industrial Area to invest in manufacturing Region plot (green field). -

Global Report on Human Settlements 2011

STATISTICAL ANNEX GENERAL DISCLAIMER The designations employed and presentation of the data do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or bound- aries. TECHNICAL NOTES The Statistical Annex comprises 16 tables covering such Tomé and Príncipe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, broad statistical categories as demography, housing, Somalia, Sudan, Timor-Leste, Togo, Tuvalu, Uganda, United economic and social indicators. The Annex is divided into Republic of Tanzania, Vanuatu, Yemen, Zambia. three sections presenting data at the regional, country and city levels. Tables A.1 to A.4 present regional-level data Small Island Developing States:1 American Samoa, grouped by selected criteria of economic and development Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Bahamas, Bahrain, achievements, as well as geographic distribution. Tables B.1 Barbados, Belize, British Virgin Islands, Cape Verde, to B.8 contain country-level data and Tables C.1 to C.3 are Comoros, Cook Islands, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican devoted to city-level data. Data have been compiled from Republic, Fiji, French Polynesia, Grenada, Guam, Guinea- various international sources, from national statistical offices Bissau, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, Kiribati, Maldives, Marshall and from the United Nations. Islands, Mauritius, Micronesia (Federated States of), Montserrat, Nauru, Netherlands Antilles, New Caledonia, Niue, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Papua New Guinea, EXPLANATION OF SYMBOLS Puerto Rico, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Samoa, São Tomé and Príncipe, The following symbols have been used in presenting data Seychelles, Solomon Islands, Suriname, Timor-Leste, Tonga, throughout the Statistical Annex: Trinidad and Tobago, Tuvalu, United States Virgin Islands, Vanuatu. -

HONEY EXPORTS from TANZANIA BUSINESS PROCESS ANALYSIS for ENHANCED EXPORT COMPETITIVENESS Digital Images on Cover: © Thinkstock.Com

HONEY EXPORTS FROM TANZANIA BUSINESS PROCESS ANALYSIS FOR ENHANCED EXPORT COMPETITIVENESS Digital images on cover: © thinkstock.com The designations employed and the presentation of material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Trade Centre concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This document has not formally been edited by the International Trade Centre. HONEY EXPORTS FROM TANZANIA Acknowledgments Ms. Namsifu Nyagabona is the author of this report. She was assisted by Mr. Christian Ksoll, International Consultant. They are wholly responsible for the information and views stated in the report. The consultants’ team acknowledges with gratitude the contributions of a number of people towards the process of this business process analysis (BPA), without whose participation the project would not have succeeded. In particular, we would like to express our gratitude and appreciation to Ben Czapnik and Giles Chappell of the Trade Facilitation and Policy for Business (TFPB) Section at the International Trade Centre (ITC), for their overall oversight, feedback and in-depth comments and guidance from the inception to the finishing of the report. We express our gratitude and thanks to the people whom we interviewed in the process of collecting information for the report. We also express our gratitude and thanks to the persons we have interviewed for the study, along with the participants in the workshop organized by the International Trade Centre (ITC) on 25 February 2016 in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. -

Dodoma, Tanzania and Socialist Modernity

The Rationalization of Space and Time: Dodoma, Tanzania and Socialist Modernity The categories of space and time are crucial variables in the constitution of what many scholars deem as modernity. However, due to the almost exclusive interpretation of space and time as components of a modernity coupled with global capitalism (Harvey 1990; Jameson 1991), discussions of a socialist space and time as a construction of an alternate modernity during the 60s and 70s—in particular across the Third World—have been neglected. Julius Nyerere’s project of collectivization, or ujamaa , in Tanzania during this period is a prime example of an attempt to develop the nation-state outside of the capitalist format. While it would be interesting to explore the connections Nyerere had with other socialist Third World countries, like China, within the international context, and their attempts at nation-building, this paper will focus on an analysis of the Tanzanian government’s decision in 1973 to move the capital of the country from the Eastern port city of Dar es Salaam to the more centrally located Dodoma. Although the Tanzanian government never completed the majority of the buildings analyzed in this paper due to a lack of funds and a diminishing political will, the exhaustive blueprinting and documentation does provide a glimpse into the conception of an African socialist modernity. The questions of primary importance are: How did moving the Tanzanian capital from Dar es Salaam to Dodoma embody Nyerere’s vision of socialist African development? Or more specifically, how did the socialist urban planning of Dodoma fit into the greater project of ujamaa and rural development? And finally, how was the planned construction of a new urban capital an attempt at a definition of socialist space and time? 1 Space, Time, and Homo Economicus In his seminal work, The Condition of Postmodernity , David Harvey explains why the categories of space and time are constantly cited as the primary way to understand a transformation in a human being’s relationship with his or her surroundings. -

Mradi Wa Umeme Wa Rusumo Kukamilika Mwezi Desemba, 2021

HABARI ZA NISHATI Bulletin ToleoToleo NambaNamba 2221 28 DisembaJulaiJanuari 1 - 1-31,1-31, 31, 2021 20202021 WaziriRAISMRADI ALIELEZA na WA Naibu UMEME Waziri WA wa NishatiBUNGERUSUMO VIPAUMBELE wafanya KUKAMILIKA kikao cha UK. SEKTA YA NISHATI 7 MWEZIkwanza DESEMBA,na Bodi za Taasisi 2021 Watoa maelekezo mahususi Waziri Mkuu azindua Waziri wa Nishati, Mhe. Dkt Medarduchepushwaji Kalemani (kushoto) na Naibu Waziri wa Nishati,wa Mhe. majiStephen Byabato Waziri wa Nishati Mhe. Dkt. Medard Kalemani, akizungumza na Waandishi wa Habari, mara baada ya Mawaziri wa nchi tatu za Tanzania, RwandaWAZIRI na Burundi KALEMANI zinazohusika na Mradi wa AUTAKA Umeme wa Rusumo UONGOZI kumaliza mkutano waoWA uliofanyika WIZARA tarehe 12 Juni, YA 2021 NISHATI baada ya kutembelea eneo la Mradi na kuridhishwaUK. na hatua ya ujenzi iliyofikiwa na wakandarasi. Kutoka kushoto ni Waziri wa Nishati Tanzania, Mhe.KUFANYA Dkt. Medard Kalemani, KAZI Waziri2 waKWA Miundombinukatika KASI, Rwanda, KWA Mhe. Balozimradi UBUNIFU Claver Gatete na Waziri NAwa wa KWA Nishati naJNHPP USAHIHIMigodi wa Burundi Mhe. Ibrahim Uwizeye. LIMEANDALIWA NA KITENGO CHA MAWASILIANO SERIKALINI, WIZARA YA NISHATI Wasiliana nasi kwa simu namba +255-26-2322018 Nukushi +255-26-2320148 au Fika Osi ya Mawasiliano, Mji Mpya wa Serikali Mtumba, S.L.P 2494, Dodoma HABARI 2 MRADI WA UMEME WA RUSUMO KUKAMILIKA MWEZI DESEMBA, 2021 Na Dorina G. Makaya - zinazohusika na Mradi Ngara wa Umeme wa Rusumo kilichofanyika katika aziri wa eneo la mradi la Rusumo. Nishati, Waziri Kalemani Mhe. alieleza kuwa, Mawaziri Dkt. wa nchi zote tatu Medard zinazohusika na Mradi WKalemani amesema, wa Rusumo, Waziri wa Mradi wa Umeme wa Nishati na Migodi wa Rusumo utakamilika Burundi, Mhe. -

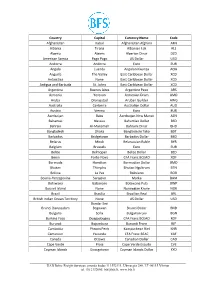

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Access of Urban Farmers to Land, Water and Inputs for Urban Agriculture in Dodoma Municipality, Tanzania

Vol. 7(1), pp. 31-40, January 2015 DOI: 10.5897/JASD2014.0302 Article Number: E7B49FE49310 Journal of African Studies and ISSN 2141 -2189 Copyright © 2015 Development Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournlas.org/JASD Full Length Research Paper Access of urban farmers to land, water and inputs for urban agriculture in Dodoma municipality, Tanzania Baltazar M.L. Namwata1*, Idris S. Kikula2 and Peter A. Kopoka3 1Department of Development Finance and Management Studies, Institute of Rural Development Planning (IRDP), Dodoma, Tanzania. 2Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, School of Social Sciences, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, the University of Dodoma (UDOM), Dodoma, Tanzania. 3Department of Political Science and Public Administration, School of Social Sciences, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, the University of Dodoma (UDOM), Dodoma, Tanzania. Received 23 September, 2014; Accepted 8 December, 2014 This paper examines the access of urban farmers to land, water and inputs for urban agriculture (UA) towards household food security, employment creation and income generation in Dodoma municipality. A cross-sectional survey was employed involving 300 urban farmers from both squatter and non- squatter settlements. Structured questionnaires, focus group discussions, key informants, observations and documentary review were used to collect data relevant for the study. Based on the analysis of this study, urban farmers are constrained by land tenure insecurity, erratic water access and inadequate inputs for optimizing plot productivity and ambivalent application of urban legislative frameworks. The study found that no support has been given to urban farmers to enable them to have access to land, water and inputs in order to practice UA. -

MKUTANO WA KUMI NA TISA Kikao Cha Ishirini Na Tano – Tarehe 8

NAKALA MTANDAO(ONLINE DOCUMENT) BUNGE LA TANZANIA __________ MAJADILIANO YA BUNGE ___________ MKUTANO WA KUMI NA TISA Kikao cha Ishirini na Tano – Tarehe 8 Mei, 2020 (Bunge Lilianza Saa Nane Mchana) D U A Naibu Spika (Mhe. Dkt. Tulia Ackson) Alisoma Dua NAIBU SPIKA: Waheshimiwa Wabunge, tukae. Katibu. NDG. LAWRANCE MAKIGI - KATIBU MEZANI: HATI ZA KUWASILISHA MEZANI Hati Zifuatazo Ziliwasilishwa Mezani na:- NAIBU WAZIRI WA NISHATI: Hotuba ya Makadirio ya Mapato na Matumizi ya Wizara ya Nishati kwa mwaka wa fedha 2020/2021. MHE. USSI SALUM PONDEZA AMJADI (K.n.y. MWENYEKITI WA KAMATI YA KUDUMU YA BUNGE YA NISHATI NA MADINI): Taarifa ya Kamati ya Kudumu ya Bunge ya Nishati na Madini kuhusu utekelezaji wa Majukumu ya Wizara ya Nishati Fungu 58 kwa mwaka wa fedha 2019/2020 pamoja na Maoni ya Kamati kuhusu Makadirio ya Mapato na Matumizi ya fedha kwa mwaka wa fedha 2020/2021. NAIBU SPIKA: Ahsante sana. Msemaji Mkuu wa Kambi Rasmi ya Upinzani Bungeni wa Wizara ya Nishati. Hayupo. Katibu. 1 NAKALA MTANDAO(ONLINE DOCUMENT) NDG. LAWRANCE MAKIGI - KATIBU MEZANI MASWALI NA MAJIBU (Maswali yafuatayo yameulizwa na kujibiwa kwa njia ya mtandao) Na. 231 Uhaba wa Walimu – Mkoa wa Tanga MHE. OMARI A. KIGODA aliuliza:- Kutokana na uhaba wa walimu Mkoa wa Tanga umekuwa haufanyi vizuri katika matokeo ya ufaulu wa wanafunzi:- Je, kuna mkakati wowote wa Serikali wa kutatua changamoto hiyo? WAZIRI WA NCHI, OFISI YA RAIS, TAWALA ZA MITAA NA SERIKALI ZA MITAA alijibu:- Mheshimiwa Spika, naomba kujibu swali la Mheshimiwa Omari Abdallah Kigoda, Mbunge wa Handeni, kama ifuatavyo:- Mheshimiwa Spika, Serikali imeendelea kuajiri Walimu wa Shule za Msingi na Sekondari nchini ambapo kuanzia mwaka 2017 hadi 2019 jumla ya walimu 420 wameajiriwa na kupangwa katika Mkoa wa Tanga.