Dodoma, Tanzania and Socialist Modernity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Tanzania in Figures

2019 Tanzania in Figures The United Republic of Tanzania 2019 TANZANIA IN FIGURES National Bureau of Statistics Dodoma June 2020 H. E. Dr. John Pombe Joseph Magufuli President of the United Republic of Tanzania “Statistics are very vital in the development of any country particularly when they are of good quality since they enable government to understand the needs of its people, set goals and formulate development programmes and monitor their implementation” H.E. Dr. John Pombe Joseph Magufuli the President of the United Republic of Tanzania at the foundation stone-laying ceremony for the new NBS offices in Dodoma December, 2017. What is the importance of statistics in your daily life? “Statistical information is very important as it helps a person to do things in an organizational way with greater precision unlike when one does not have. In my business, for example, statistics help me know where I can get raw materials, get to know the number of my customers and help me prepare products accordingly. Indeed, the numbers show the trend of my business which allows me to predict the future. My customers are both locals and foreigners who yearly visit the region. In June every year, I gather information from various institutions which receive foreign visitors here in Dodoma. With estimated number of visitors in hand, it gives me ample time to prepare products for my clients’ satisfaction. In terms of my daily life, Statistics help me in understanding my daily household needs hence make proper expenditures.” Mr. Kulwa James Zimba, Artist, Sixth street Dodoma.”. What is the importance of statistics in your daily life? “Statistical Data is useful for development at family as well as national level because without statistics one cannot plan and implement development plans properly. -

Organized Crime and Instability in Central Africa

Organized Crime and Instability in Central Africa: A Threat Assessment Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: +(43) (1) 26060-0, Fax: +(43) (1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org OrgAnIzed CrIme And Instability In CenTrAl AFrica A Threat Assessment United Nations publication printed in Slovenia October 2011 – 750 October 2011 UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Organized Crime and Instability in Central Africa A Threat Assessment Copyright © 2011, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Acknowledgements This study was undertaken by the UNODC Studies and Threat Analysis Section (STAS), Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs (DPA). Researchers Ted Leggett (lead researcher, STAS) Jenna Dawson (STAS) Alexander Yearsley (consultant) Graphic design, mapping support and desktop publishing Suzanne Kunnen (STAS) Kristina Kuttnig (STAS) Supervision Sandeep Chawla (Director, DPA) Thibault le Pichon (Chief, STAS) The preparation of this report would not have been possible without the data and information reported by governments to UNODC and other international organizations. UNODC is particularly thankful to govern- ment and law enforcement officials met in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda and Uganda while undertaking research. Special thanks go to all the UNODC staff members - at headquarters and field offices - who reviewed various sections of this report. The research team also gratefully acknowledges the information, advice and comments provided by a range of officials and experts, including those from the United Nations Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, MONUSCO (including the UN Police and JMAC), IPIS, Small Arms Survey, Partnership Africa Canada, the Polé Institute, ITRI and many others. -

Tanzania 2018 International Religious Freedom Report

TANZANIA 2018 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitutions of the union government and of the semiautonomous government in Zanzibar both prohibit religious discrimination and provide for freedom of religious choice. Since independence, the country has been governed by alternating Christian and Muslim presidents. Sixty-one members of Uamsho, an Islamist group advocating for Zanzibar’s full autonomy, remained in custody without a trial since their arrest in 2013 under terrorism charges. In May the Office of the Registrar of Societies, an entity within the Ministry of Home Affairs charged with overseeing religious organizations, released a letter ordering the leadership of the Catholic and Lutheran Churches to retract statements that condemned the government for increasing restrictions on freedoms of speech and assembly, and alleged human rights abuses. After a public outcry, the minister of home affairs denounced the letter and suspended the registrar. The Zanzibar Ministry of Agriculture and Natural Resources destroyed a church being built on property owned by the Pentecostal Assemblies of God after the High Court of Zanzibar ruled the church was built on government property. This followed a protracted court battle in which Zanzibar courts ruled the church was allowed on the property. Vigilante killings of persons accused of practicing witchcraft continued to occur. As of July, the government reported 117 witchcraft-related incidents. There were some attacks on churches and mosques throughout the country, especially in rural regions. Civil society groups continued to promote peaceful interactions and religious tolerance. The embassy launched a three-month public diplomacy campaign in support of interfaith dialogue and sponsored the visit of an imam from the United States to discuss interfaith and religious freedom topics with government officials and civil society. -

CHOLERA COUNTRY PROFILE: United Republic of TANZANIA 7 April 2008

WO RLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION Global Task Force on Cholera Control CHOLERA COUNTRY PROFILE: United Republic of TANZANIA 7 April 2008 General Country Information: The United Republic of Tanzania is located in East Africa and borders Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Zambia, Malawi and Mozambique. It has a long east coast along the Indian Ocean. Tanzania is divided into 26 regions (21 on the mainland and five in Zanzibar). Dodoma is the capital (only since 1996) but Dar es Salaam is the largest city and a very important economic centre for the region. In 1880, Tanzania became a German colony (it was then named Tanganyika). After the end of World War I, in1919, it became a British Mandate which was to last until independence in 1961. Tanganyika and neighboring Zanzibar, which had become independent in 1963 merged to form the nation of Tanzania on 26 April 1964. The economy of Tanzania is highly dependant on agriculture, however only 4% of land area is used for cultivated crops due to climatic and topography conditions. It also has vast amounts of natural resources such as gold. Tanzania's Human Development Index is 159 over 177. HIV prevalence has decreased from 9.6% in 2002 to 5.9% in 2005. Cholera Background History: The first 10 cholera cases were reported in 1974 and since 1977, cases were reported each year with a case fatality rate (CFR) averaging 10.5% (between 1977 and 1992). The first major outbreak occurred in 1992 when 18'526 United Republic of Tanzania cases including 2'173 deaths were recorded. -

Working Paper February 2021 CONTENTS

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF SUNFLOWER IN TANZANIA: A CASE OF SINGIDA REGION Aida C. Isinika and John Jeckoniah WP 49 Working Paper February 2021 CONTENTS Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................... 4 Acronyms ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Executive summary ........................................................................................................................... 6 1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………….................................... 7 2 Methodology………………………………………………………………………... ............................... 8 3 Trends in sunflower value chain……………………………………………………. ........................... 9 3.1 Supply and demand ......................................................................................................... 9 3.2 Trend of sunflower production and processing .................................................................. 9 3.3 Increasing processing capacity ....................................................................................... 10 3.4 The role of imports and exports ...................................................................................... 11 4 The sunflower subsector ............................................................................................................ 13 4.1 The market map……………………………………………………………………. ............... 13 4.2 Relations within the sunflower -

Dar Es Salaam-Ch1.P65

Chapter One The Emerging Metropolis: A history of Dar es Salaam, circa 1862-2000 James R. Brennan and Andrew Burton This chapter offers an overview history of Dar es Salaam. It proceeds chronologically from the town’s inception in the 1860s to its present-day status as one of the largest cities in Africa. Within this sequential structure are themes that resurface in later chapters. Dar es Salaam is above all a site of juxtaposition between the local, the national, and the cosmopolitan. Local struggles for authority between Shomvi and Zaramo, as well as Shomvi and Zaramo indigenes against upcountry immigrants, stand alongside racialized struggles between Africans and Indians for urban space, global struggles between Germany and Britain for military control, and national struggles between European colonial officials and African nationalists for political control. Not only do local, national, and cosmopolitan contexts reveal the layers of the town’s social cleavages, they also reveal the means and institutions of social and cultural belonging. Culturally Dar es Salaam represents a modern reformulation of the Swahili city. Indeed it might be argued that, partly due to the lack of dominant founding fathers and an established urban society pre- dating its rapid twentieth century growth, this late arrival on the East African coast is the contemporary exemplar of Swahili virtues of cosmopolitanism and cultural exchange. Older coastal cities of Mombasa and Zanzibar struggle to match Dar es Salaam in its diversity and, paradoxically, its high degree of social integration. Linguistically speaking, it is without doubt a Swahili city; one in which this language of nineteenth-century economic incorporation has flourished as a twentieth-century vehicle of social and cultural incorporation for migrants from the African interior as well as from the shores of the western Indian Ocean. -

African Development Bank United Republic of Tanzania

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA DODOMA CITY OUTER RING ROAD (110.2 km) CONSTRUCTION PROJECT APPRAISAL REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure RDGE/PICU DEPARTMENTS April 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. STRATEGIC THRUST AND JUSTIFICATIONS ............................................................................... 1 1.1 PROJECT LINKAGES WITH NATIONAL AND REGIONAL STRATEGIES ........................................................ 1 1.2 RATIONALE FOR BANK INVOLVEMENT .................................................................................................. 1 1.3 AID COORDINATION ............................................................................................................................. 2 II. PROJECT DESCRIPTION ................................................................................................................... 2 2.1 PROJECT OBJECTIVES ........................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 PROJECT COMPONENTS ........................................................................................................................ 3 2.3 TECHNICAL SOLUTIONS ADOPTED AND ALTERNATIVES CONSIDERED .................................................... 3 2.4 PROJECT TYPE ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2.5 PROJECT COST AND FINANCING MECHANISMS ..................................................................................... -

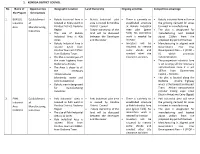

1. KONDOA DISTRICT COUNCIL No Name of the Project Opportunities

1. KONDOA DISTRICT COUNCIL No Name of Opportunities Geographic Location Land Ownership Ongoing activities Competitive advantage the Project for investors 1. BUKULU Establishment Bukulu Industrial Area is Bukulu Industrial plot There is currently no Bukulu Industrial Area will serve Industrial of Located at Soera ward in area is owned by Kondoa established structure the growing demand for areas Area Manufacturing Kondoa District, Dodoma District Council at Bukulu Industrial to invest in manufacturing Industries Region Future ownership of the Area plot (green The plot is designated for The size of Bukulu land will be discussed field). No demolition manufacturing and located Industrial Area is 400 between the Developer work is needed by about 220km from the Acres and the owner Investor proposed dry port of Ihumwa Bukulu Industrial Area is Investors will be Manufacturing is aligned with located 47km from required to remove Government Five Year Kondoa Town and 197km some shrubs and Development Plan – II (FYDP – from Dodoma Town. conduct other site II) which promotes The Plot is located just off clearance activities industrialisation the main highway from The prospective Industrial Area Dodoma to Arusha is set to enjoy all the necessary The Area is closer to all infrastructures since it is just the necessary 197km from Government infrastructures Capital – Dodoma (electricity, water and The plot is located along the communications) Dodoma – Arusha highway Bukulu area is designated which is the longest and busiest for manufacturing Trans – African transportation Industries corridor linking Cape Town (South Africa) and Cairo (Egypt) 2. PAHI Establishment Pahi Industrial Area is Pahi Industrial plot area There is currently no Pahi Industrial Area will serve Industrial of Located at Pahi ward in is owned by Kondoa established structure the growing demand for areas Area Manufacturing Kondoa District, Dodoma District Council at Pahi Industrial Area to invest in manufacturing Region plot (green field). -

Tanzania MFR Summary Report

TANZANIA August 20, 2018 Market Fundamentals Summary KEY MESSAGES The objective of this report is to document the basic market context Figure 1. Map of Tanzania for staple food and livestock production and marketing in Tanzania. The information presented is based on desk research, a field assessment using rapid rural appraisal techniques, and a consultation workshop with stakehoders in Tanzania. Findings from this report will inform regular market monitoring and analysis in Tanzania. Maize, rice, sorghum, millet, pulses (beans and peas), cassava and bananas (plantains) are the main staple foods in Tanzania. Maize is the most widely consumed staple in Tanzania and the country imports significant quantities of wheat to meet local demand for wheat flour. Consumption of other staples varies across the country based on local supply and demand dynamics. Cattle, goat and sheep are the major sources of red meat consumed in Tanzania. Tanzania’s cropping calendar follows two distinct seasonal patterns. The Msimu season covers unimodal rainfall areas in the south, west and central parts of the country while the Masika and Vuli seasons Source: FEWS NET (2018). cover bi-modal rainfall areas in the north and eastern parts of the country (Figure 5). Figure 2. Tanzania’s average self sufficiency status for key staple foods (2014/15 – 2017/18) As a member of the East Africa Community (EAC) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC), Tanzania plays an important role in regional staple food trade across East and Southern Africa (Annex III). The country is generally a surplus producer of staple cereals and pulses, and exports significant quantities of these commodities to neighboring countries in East and Southern Africa inlcuding Kenya, Malawi, Zambia, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and the Democratice Republic of Congo (Figure 2). -

Global Report on Human Settlements 2011

STATISTICAL ANNEX GENERAL DISCLAIMER The designations employed and presentation of the data do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or bound- aries. TECHNICAL NOTES The Statistical Annex comprises 16 tables covering such Tomé and Príncipe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, broad statistical categories as demography, housing, Somalia, Sudan, Timor-Leste, Togo, Tuvalu, Uganda, United economic and social indicators. The Annex is divided into Republic of Tanzania, Vanuatu, Yemen, Zambia. three sections presenting data at the regional, country and city levels. Tables A.1 to A.4 present regional-level data Small Island Developing States:1 American Samoa, grouped by selected criteria of economic and development Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Bahamas, Bahrain, achievements, as well as geographic distribution. Tables B.1 Barbados, Belize, British Virgin Islands, Cape Verde, to B.8 contain country-level data and Tables C.1 to C.3 are Comoros, Cook Islands, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican devoted to city-level data. Data have been compiled from Republic, Fiji, French Polynesia, Grenada, Guam, Guinea- various international sources, from national statistical offices Bissau, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, Kiribati, Maldives, Marshall and from the United Nations. Islands, Mauritius, Micronesia (Federated States of), Montserrat, Nauru, Netherlands Antilles, New Caledonia, Niue, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Papua New Guinea, EXPLANATION OF SYMBOLS Puerto Rico, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Samoa, São Tomé and Príncipe, The following symbols have been used in presenting data Seychelles, Solomon Islands, Suriname, Timor-Leste, Tonga, throughout the Statistical Annex: Trinidad and Tobago, Tuvalu, United States Virgin Islands, Vanuatu. -

HONEY EXPORTS from TANZANIA BUSINESS PROCESS ANALYSIS for ENHANCED EXPORT COMPETITIVENESS Digital Images on Cover: © Thinkstock.Com

HONEY EXPORTS FROM TANZANIA BUSINESS PROCESS ANALYSIS FOR ENHANCED EXPORT COMPETITIVENESS Digital images on cover: © thinkstock.com The designations employed and the presentation of material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Trade Centre concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This document has not formally been edited by the International Trade Centre. HONEY EXPORTS FROM TANZANIA Acknowledgments Ms. Namsifu Nyagabona is the author of this report. She was assisted by Mr. Christian Ksoll, International Consultant. They are wholly responsible for the information and views stated in the report. The consultants’ team acknowledges with gratitude the contributions of a number of people towards the process of this business process analysis (BPA), without whose participation the project would not have succeeded. In particular, we would like to express our gratitude and appreciation to Ben Czapnik and Giles Chappell of the Trade Facilitation and Policy for Business (TFPB) Section at the International Trade Centre (ITC), for their overall oversight, feedback and in-depth comments and guidance from the inception to the finishing of the report. We express our gratitude and thanks to the people whom we interviewed in the process of collecting information for the report. We also express our gratitude and thanks to the persons we have interviewed for the study, along with the participants in the workshop organized by the International Trade Centre (ITC) on 25 February 2016 in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. -

13. Laddunnuri Maternal Mortatlity Tanzaniax

International Journal of Caring Sciences 2013 May - August Vol 6 Issue 2 236 . O R I G I N A L P A P E R .r . Maternal Mortality in Rural Areas of Dodoma Region, Tanzania: a Qualitative Study Madan Mohan Laddunuri, PhD Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Dodoma University, Dodoma, Tanzania Coresponcence: Dr Madan Mohan Laddunuri, Post Box 259 Dodoma university, Dodoma, Tanzania. E-mail [email protected] Abstract Background: A major public health concern in Tanzania is the high rate of maternal deaths as the estimated Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) is 454 per 100,000 live births (TDHS, 2010). The main objective of the present study was to find out the contributing factors to maternal mortality in rural areas of Dodoma region of Tanzania. Methodology: The verbal autopsy technique was used to reconstruct “the road to maternal death.” A structured open-ended questionnaire was developed on the basis of the “three delays” model: delay in the decision to seek care, delay in arrival at a health facility and delay in the provision of adequate care. The sample comprised of 20 cases, 4 for each district of Dodoma. Data were collected by conducting in-depth interviews with close relatives of the deceased women and those who accompanied the women (neighbours) during the time the illness developed to death. Results: There was delay in receiving appropriate medical care and that eventually lead to the death of the pregnant woman, due to underestimation of the severity of the complication, bad experience with the health care system, delay in reaching an appropriate medical facility, lack of transportation, or delay in receiving appropriate care after reaching to the hospital.